- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Christopher Columbus

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 11, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

The explorer Christopher Columbus made four trips across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain: in 1492, 1493, 1498 and 1502. He was determined to find a direct water route west from Europe to Asia, but he never did. Instead, he stumbled upon the Americas. Though he did not “discover” the so-called New World—millions of people already lived there—his journeys marked the beginning of centuries of exploration and colonization of North and South America.

Christopher Columbus and the Age of Discovery

During the 15th and 16th centuries, leaders of several European nations sponsored expeditions abroad in the hope that explorers would find great wealth and vast undiscovered lands. The Portuguese were the earliest participants in this “ Age of Discovery ,” also known as “ Age of Exploration .”

Starting in about 1420, small Portuguese ships known as caravels zipped along the African coast, carrying spices, gold and other goods as well as enslaved people from Asia and Africa to Europe.

Did you know? Christopher Columbus was not the first person to propose that a person could reach Asia by sailing west from Europe. In fact, scholars argue that the idea is almost as old as the idea that the Earth is round. (That is, it dates back to early Rome.)

Other European nations, particularly Spain, were eager to share in the seemingly limitless riches of the “Far East.” By the end of the 15th century, Spain’s “ Reconquista ”—the expulsion of Jews and Muslims out of the kingdom after centuries of war—was complete, and the nation turned its attention to exploration and conquest in other areas of the world.

Early Life and Nationality

Christopher Columbus, the son of a wool merchant, is believed to have been born in Genoa, Italy, in 1451. When he was still a teenager, he got a job on a merchant ship. He remained at sea until 1476, when pirates attacked his ship as it sailed north along the Portuguese coast.

The boat sank, but the young Columbus floated to shore on a scrap of wood and made his way to Lisbon, where he eventually studied mathematics, astronomy, cartography and navigation. He also began to hatch the plan that would change the world forever.

Christopher Columbus' First Voyage

At the end of the 15th century, it was nearly impossible to reach Asia from Europe by land. The route was long and arduous, and encounters with hostile armies were difficult to avoid. Portuguese explorers solved this problem by taking to the sea: They sailed south along the West African coast and around the Cape of Good Hope.

But Columbus had a different idea: Why not sail west across the Atlantic instead of around the massive African continent? The young navigator’s logic was sound, but his math was faulty. He argued (incorrectly) that the circumference of the Earth was much smaller than his contemporaries believed it was; accordingly, he believed that the journey by boat from Europe to Asia should be not only possible, but comparatively easy via an as-yet undiscovered Northwest Passage .

He presented his plan to officials in Portugal and England, but it was not until 1492 that he found a sympathetic audience: the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile .

Columbus wanted fame and fortune. Ferdinand and Isabella wanted the same, along with the opportunity to export Catholicism to lands across the globe. (Columbus, a devout Catholic, was equally enthusiastic about this possibility.)

Columbus’ contract with the Spanish rulers promised that he could keep 10 percent of whatever riches he found, along with a noble title and the governorship of any lands he should encounter.

Where Did Columbus' Ships, Niña, Pinta and Santa Maria, Land?

On August 3, 1492, Columbus and his crew set sail from Spain in three ships: the Niña , the Pinta and the Santa Maria . On October 12, the ships made landfall—not in the East Indies, as Columbus assumed, but on one of the Bahamian islands, likely San Salvador.

For months, Columbus sailed from island to island in what we now know as the Caribbean, looking for the “pearls, precious stones, gold, silver, spices, and other objects and merchandise whatsoever” that he had promised to his Spanish patrons, but he did not find much. In January 1493, leaving several dozen men behind in a makeshift settlement on Hispaniola (present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic), he left for Spain.

He kept a detailed diary during his first voyage. Christopher Columbus’s journal was written between August 3, 1492, and November 6, 1492 and mentions everything from the wildlife he encountered, like dolphins and birds, to the weather to the moods of his crew. More troublingly, it also recorded his initial impressions of the local people and his argument for why they should be enslaved.

“They… brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things, which they exchanged for the glass beads and hawks’ bells," he wrote. "They willingly traded everything they owned… They were well-built, with good bodies and handsome features… They do not bear arms, and do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron… They would make fine servants… With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.”

Columbus gifted the journal to Isabella upon his return.

Christopher Columbus's Later Voyages

About six months later, in September 1493, Columbus returned to the Americas. He found the Hispaniola settlement destroyed and left his brothers Bartolomeo and Diego Columbus behind to rebuild, along with part of his ships’ crew and hundreds of enslaved indigenous people.

Then he headed west to continue his mostly fruitless search for gold and other goods. His group now included a large number of indigenous people the Europeans had enslaved. In lieu of the material riches he had promised the Spanish monarchs, he sent some 500 enslaved people to Queen Isabella. The queen was horrified—she believed that any people Columbus “discovered” were Spanish subjects who could not be enslaved—and she promptly and sternly returned the explorer’s gift.

In May 1498, Columbus sailed west across the Atlantic for the third time. He visited Trinidad and the South American mainland before returning to the ill-fated Hispaniola settlement, where the colonists had staged a bloody revolt against the Columbus brothers’ mismanagement and brutality. Conditions were so bad that Spanish authorities had to send a new governor to take over.

Meanwhile, the native Taino population, forced to search for gold and to work on plantations, was decimated (within 60 years after Columbus landed, only a few hundred of what may have been 250,000 Taino were left on their island). Christopher Columbus was arrested and returned to Spain in chains.

In 1502, cleared of the most serious charges but stripped of his noble titles, the aging Columbus persuaded the Spanish crown to pay for one last trip across the Atlantic. This time, Columbus made it all the way to Panama—just miles from the Pacific Ocean—where he had to abandon two of his four ships after damage from storms and hostile natives. Empty-handed, the explorer returned to Spain, where he died in 1506.

Legacy of Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus did not “discover” the Americas, nor was he even the first European to visit the “New World.” (Viking explorer Leif Erikson had sailed to Greenland and Newfoundland in the 11th century.)

However, his journey kicked off centuries of exploration and exploitation on the American continents. The Columbian Exchange transferred people, animals, food and disease across cultures. Old World wheat became an American food staple. African coffee and Asian sugar cane became cash crops for Latin America, while American foods like corn, tomatoes and potatoes were introduced into European diets.

Today, Columbus has a controversial legacy —he is remembered as a daring and path-breaking explorer who transformed the New World, yet his actions also unleashed changes that would eventually devastate the native populations he and his fellow explorers encountered.

HISTORY Vault: Columbus the Lost Voyage

Ten years after his 1492 voyage, Columbus, awaiting the gallows on criminal charges in a Caribbean prison, plotted a treacherous final voyage to restore his reputation.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- ALL OVER THE MAP

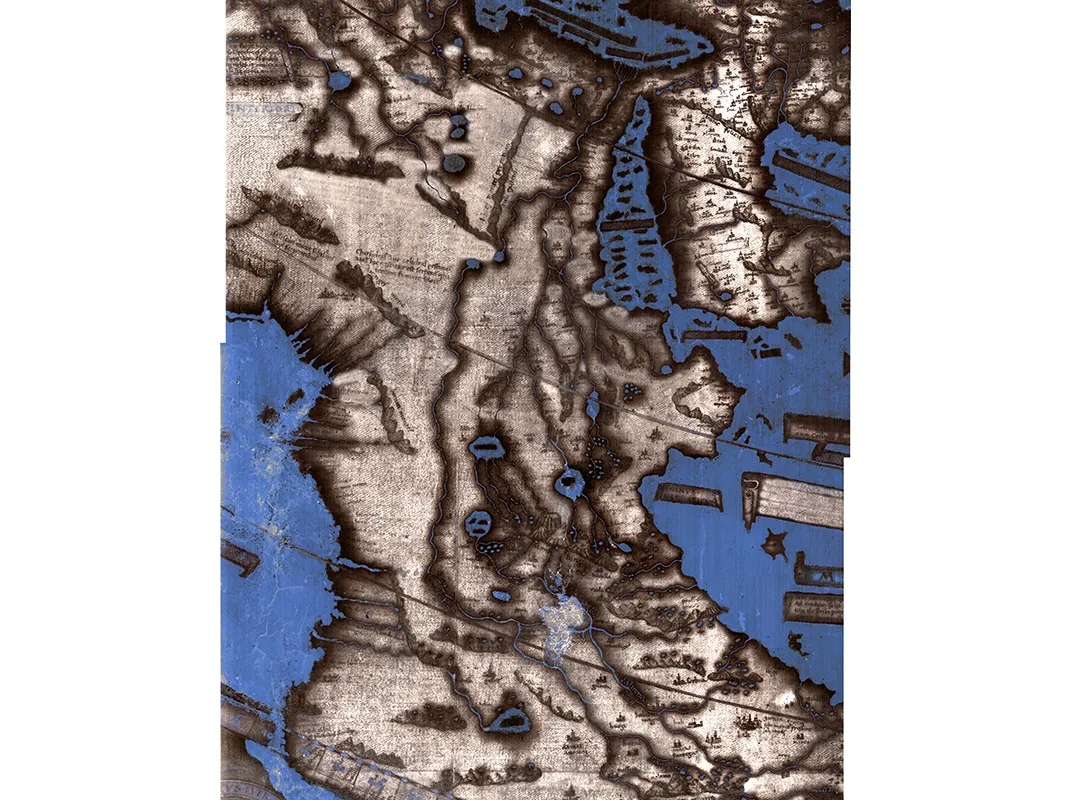

A 500-year-old map used by Columbus reveals its secrets

Newly uncovered text opens a time capsule of one of history’s most influential maps.

This 1491 map is the best surviving map of the world as Christopher Columbus knew it as he made his first voyage across the Atlantic. In fact, Columbus likely used a copy of it in planning his journey.

The map, created by the German cartographer Henricus Martellus, was originally covered with dozens of legends and bits of descriptive text, all in Latin. Most of it has faded over the centuries.

But now researchers have used modern technology to uncover much of this previously illegible text. In the process, they’ve discovered new clues about the sources Martellus used to make his map and confirmed the huge influence it had on later maps, including a famous 1507 map by Martin Waldseemuller that was the first to use the name “America.”

MARTELLUS AND COLUMBUS

Contrary to popular myth, 15th-century Europeans did not believe that Columbus would sail off the edge of a flat Earth, says Chet Van Duzer, the map scholar who led the study. But their understanding of the world was quite different from ours, and Martellus’s map reflects that.

Its depiction of Europe and the Mediterranean Sea is more or less accurate, or at least recognizable. But southern Africa is oddly shaped like a boot with its toe pointing to the east, and Asia is also twisted out of shape. The large island in the South Pacific roughly where Australia can actually be found must have been a lucky guess, Van Duzer says, as Europeans wouldn’t discover that continent for another century. Martellus filled the southern Pacific Ocean with imaginary islands, apparently sharing the common mapmakers’ aversion to empty spaces .

Another quirk of Martellus’s geography helps tie his map to Columbus’s journey: the orientation of Japan. At the time the map was created, Europeans knew Japan existed, but knew very little about its geography. Marco Polo’s journals, the best available source of information about East Asia at the time, had nothing to say about the island’s orientation.

Martellus’s map shows it running north-south. Correct, but almost certainly another lucky guess says Van Duzer, as no other known map of the time shows Japan unambiguously oriented this way. Columbus’s son Ferdinand later wrote that his father believed Japan to be oriented north-south, indicating that he very likely used Martellus’s map as a reference.

When Columbus made landfall in the West Indies on October 12, 1492, he began looking for Japan, still believing that he’d achieved his goal of finding a route to Asia. He was likely convinced Japan must be near because he’d travelled roughly the same distance that Martellus’s map suggests lay between Europe and Japan, Van Duzer argues in a new book detailing his findings.

Van Duzer says it’s reasonable to speculate that as Columbus sailed down the coast of Central and South America on later voyages, he pictured himself sailing down the coast of Asia as depicted on Martellus’s map.

You May Also Like

Gettysburg was no ordinary battle. These maps reveal how Lee lost the fight.

These enigmatic documents have kept their secrets for centuries

This European map inspired a playful cartography craze 500 years ago

Restoring a time capsule.

The map is roughly 3.5 by 6 feet. Such a large map would have been a luxury object, likely commissioned by a member of the nobility, but there’s no shield or dedication to indicate who that might have been. It was donated anonymously to Yale University in 1962 and remains in the university’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Over time, much of the text had faded to almost perfectly match the background, making it impossible to read. But in 2014 Van Duzer won a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities that allowed him and a team of collaborators to use a technique called multispectral imaging to try to uncover the hidden text.

The method involved taking many hundreds of photographs of the map with different wavelengths of light and processing the images to find the combination of wavelengths that best improves legibility on each part of the map (you can play around with an interactive map created by one of Van Duzer’s colleagues here ).

Many of the map legends describe the regions of the world and their inhabitants. “Here are found the Hippopodes: they have a human form but the feet of horses,” reads one previously illegible text over Central Asia. Another describes “monsters similar to humans whose ears are so large that they can cover their whole body.” Many of these fantastical creatures can be traced to texts written by the ancient Greeks.

The most surprising revelation, however, was in the interior of Africa, Van Duzer says. Martellus included many details and place names that appear to trace back to an Ethiopian delegation that visited Florence in 1441. Van Duzer says he knows of no other 15th-century European map that has this much information about the geography of Africa, let alone information derived from native Africans instead of European explorers. “I was blown away,” he says.

The imaging also strengthens the case that Martellus’s map was a major source for two even more famous cartographic objects: the oldest surviving terrestrial globe , created by Martin Behaim in 1492, and Martin Waldseemuller’s 1507 world map , the first to apply the label “America” to the continents of the western hemisphere. (The Library of Congress purchased Waldseemuller’s map for a record $10 million in 2003.)

Waldseemuller liberally copied text from Martellus, Van Duzer found after comparing the two maps. The practice was common in those days—in fact, Martellus himself apparently copied the sea monsters on his map from an encyclopedia published in 1491, an observation that helps date the map.

Despite their commonalities, the maps by Martellus and Waldseemuller have one glaring difference. Martellus depicts Europe and Africa nearly at the left edge of his map, with only water beyond. Waldseemuller’s map extends further to the west and depicts new lands on the other side of the Atlantic. Only 16 years had passed between the making of the two maps, but the world had changed forever.

Greg Miller and Betsy Mason are authors of the forthcoming illustrated book from National Geographic, All Over the Map . Follow the blog on Twitter and Instagram .

Related Topics

- AGE OF DISCOVERY

The lost continent of Zealandia has been mapped for the first time

Legendary Spanish galleon shipwreck discovered on Oregon coast

Vlad the Impaler's thirst for blood was an inspiration for Count Dracula

Magellan got the credit, but this man was first to sail around the world

Swastika Mountain needed a new name. Here’s how it got one.

- Environment

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

The Ages of Exploration

Christopher columbus, age of discovery.

Quick Facts:

He is credited for discovering the Americas in 1492, although we know today people were there long before him; his real achievement was that he opened the door for more exploration to a New World.

Name : Christopher Columbus [Kri-stə-fər] [Kə-luhm-bəs]

Birth/Death : 1451 - 1506

Nationality : Italian

Birthplace : Genoa, Italy

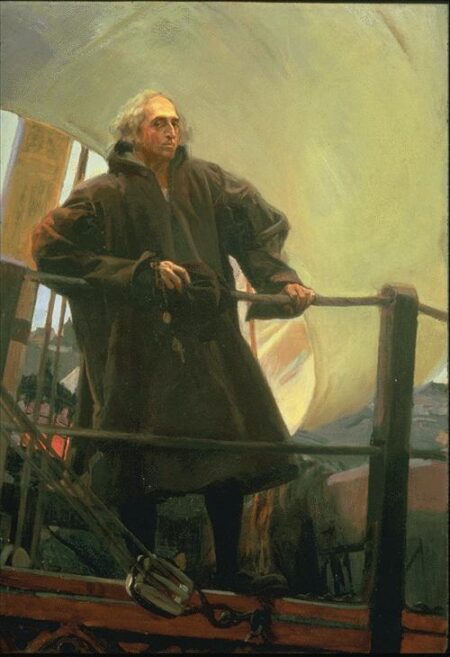

Christopher Columbus leaving Palos, Spain

Christopher Columbus aboard the "Santa Maria" leaving Palos, Spain on his first voyage across the Atlantic Ocean. The Mariners' Museum 1933.0746.000001

Introduction We know that In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue. But what did he actually discover? Christopher Columbus (also known as (Cristoforo Colombo [Italian]; Cristóbal Colón [Spanish]) was an Italian explorer credited with the “discovery” of the America’s. The purpose for his voyages was to find a passage to Asia by sailing west. Never actually accomplishing this mission, his explorations mostly included the Caribbean and parts of Central and South America, all of which were already inhabited by Native groups.

Biography Early Life Christopher Columbus was born in Genoa, part of present-day Italy, in 1451. His parents’ names were Dominico Colombo and Susanna Fontanarossa. He had three brothers: Bartholomew, Giovanni, and Giacomo; and a sister named Bianchinetta. Christopher became an apprentice in his father’s wool weaving business, but he also studied mapmaking and sailing as well. He eventually left his father’s business to join the Genoese fleet and sail on the Mediterranean Sea. 1 After one of his ships wrecked off the coast of Portugal, he decided to remain there with his younger brother Bartholomew where he worked as a cartographer (mapmaker) and bookseller. Here, he married Doña Felipa Perestrello e Moniz and had two sons Diego and Fernando.

Christopher Columbus owned a copy of Marco Polo’s famous book, and it gave him a love for exploration. In the mid 15th century, Portugal was desperately trying to find a faster trade route to Asia. Exotic goods such as spices, ivory, silk, and gems were popular items of trade. However, Europeans often had to travel through the Middle East to reach Asia. At this time, Muslim nations imposed high taxes on European travels crossing through. 2 This made it both difficult and expensive to reach Asia. There were rumors from other sailors that Asia could be reached by sailing west. Hearing this, Christopher Columbus decided to try and make this revolutionary journey himself. First, he needed ships and supplies, which required money that he did not have. He went to King John of Portugal who turned him down. He then went to the rulers of England, and France. Each declined his request for funding. After seven years of trying, he was finally sponsored by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain.

Voyages Principal Voyage Columbus’ voyage departed in August of 1492 with 87 men sailing on three ships: the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María. Columbus commanded the Santa María, while the Niña was led by Vicente Yanez Pinzon and the Pinta by Martin Pinzon. 3 This was the first of his four trips. He headed west from Spain across the Atlantic Ocean. On October 12 land was sighted. He gave the first island he landed on the name San Salvador, although the native population called it Guanahani. 4 Columbus believed that he was in Asia, but was actually in the Caribbean. He even proposed that the island of Cuba was a part of China. Since he thought he was in the Indies, he called the native people “Indians.” In several letters he wrote back to Spain, he described the landscape and his encounters with the natives. He continued sailing throughout the Caribbean and named many islands he encountered after his ship, king, and queen: La Isla de Santa María de Concepción, Fernandina, and Isabella.

It is hard to determine specifically which islands Columbus visited on this voyage. His descriptions of the native peoples, geography, and plant life do give us some clues though. One place we do know he stopped was in present-day Haiti. He named the island Hispaniola. Hispaniola today includes both Haiti and the Dominican Republic. In January of 1493, Columbus sailed back to Europe to report what he found. Due to rough seas, he was forced to land in Portugal, an unfortunate event for Columbus. With relations between Spain and Portugal strained during this time, Ferdinand and Isabella suspected that Columbus was taking valuable information or maybe goods to Portugal, the country he had lived in for several years. Those who stood against Columbus would later use this as an argument against him. Eventually, Columbus was allowed to return to Spain bringing with him tobacco, turkey, and some new spices. He also brought with him several natives of the islands, of whom Queen Isabella grew very fond.

Subsequent Voyages Columbus took three other similar trips to this region. His second voyage in 1493 carried a large fleet with the intention of conquering the native populations and establishing colonies. At one point, the natives attacked and killed the settlers left at Fort Navidad. Over time the colonists enslaved many of the natives, sending some to Europe and using many to mine gold for the Spanish settlers in the Caribbean. The third trip was to explore more of the islands and mainland South America further. Columbus was appointed the governor of Hispaniola, but the colonists, upset with Columbus’ leadership appealed to the rulers of Spain, who sent a new governor: Francisco de Bobadilla. Columbus was taken prisoner on board a ship and sent back to Spain.

On his fourth and final journey west in 1502 Columbus’s goal was to find the “Strait of Malacca,” to try to find India. But a hurricane, then being denied entrance to Hispaniola, and then another storm made this an unfortunate trip. His ship was so badly damaged that he and his crew were stranded on Jamaica for two years until help from Hispaniola finally arrived. In 1504, Columbus and his men were taken back to Spain .

Later Years and Death Columbus reached Spain in November 1504. He was not in good health. He spent much of the last of his life writing letters to obtain the percentage of wealth overdue to be paid to him, and trying to re-attain his governorship status, but was continually denied both. Columbus died at Valladolid on May 20, 1506, due to illness and old age. Even until death, he still firmly believing that he had traveled to the eastern part of Asia.

Legacy Columbus never made it to Asia, nor did he truly discover America. His “re-discovery,” however, inspired a new era of exploration of the American continents by Europeans. Perhaps his greatest contribution was that his voyages opened an exchange of goods between Europe and the Americas both during and long after his journeys. 5 Despite modern criticism of his treatment of the native peoples there is no denying that his expeditions changed both Europe and America. Columbus day was made a federal holiday in 1971. It is recognized on the second Monday of October.

- Fergus Fleming, Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration (New York: Grove Press, 2004), 30.

- Fleming, Off the Map, 30

- William D. Phillips and Carla Rahn Phillips, The Worlds of Christopher Columbus (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 142-143.

- Phillips and Phillips, The Worlds of Christopher Columbus, 155.

- Robin S. Doak, Christopher Columbus: Explorer of the New World (Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2005), 92.

Bibliography

Doak, Robin. Christopher Columbus: Explorer of the New World. Minneapolis: Compass Point Books, 2005.

Fleming, Fergus. Off the Map: Tales of Endurance and Exploration. New York: Grove Press, 2004.

Phillips, William D., and Carla Rahn Phillips. The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Map of Voyages

Click below to view an example of the explorer’s voyages. Use the tabs on the left to view either 1 or multiple journeys at a time, and click on the icons to learn more about the stops, sites, and activities along the way.

- Original "EXPLORATION through the AGES" site

- The Mariners' Educational Programs

The Four Voyages of Columbus, 1492–1503

Account Options

The First New World Voyage of Christopher Columbus (1492)

European Exploration of the Americas

Spencer Arnold/Getty Images

- Ph.D., Spanish, Ohio State University

- M.A., Spanish, University of Montana

- B.A., Spanish, Penn State University

How was the first voyage of Columbus to the New World undertaken, and what was its legacy? Having convinced the King and Queen of Spain to finance his voyage, Christopher Columbus departed mainland Spain on August 3, 1492. He quickly made port in the Canary Islands for a final restocking and left there on September 6. He was in command of three ships: the Pinta, the Niña, and the Santa María. Although Columbus was in overall command, the Pinta was captained by Martín Alonso Pinzón and the Niña by Vicente Yañez Pinzón.

First Landfall: San Salvador

On October 12, Rodrigo de Triana, a sailor aboard the Pinta, first sighted land. Columbus himself later claimed that he had seen a sort of light or aura before Triana did, allowing him to keep the reward he had promised to give to whoever spotted land first. The land turned out to be a small island in the present-day Bahamas. Columbus named the island San Salvador, although he remarked in his journal that the natives referred to it as Guanahani. There is some debate over which island was Columbus’ first stop; most experts believe it to be San Salvador, Samana Cay, Plana Cays or Grand Turk Island.

Second Landfall: Cuba

Columbus explored five islands in the modern-day Bahamas before he made it to Cuba. He reached Cuba on October 28, making landfall at Bariay, a harbor near the eastern tip of the island. Thinking he had found China, he sent two men to investigate. They were Rodrigo de Jerez and Luis de Torres, a converted Jew who spoke Hebrew, Aramaic, and Arabic in addition to Spanish. Columbus had brought him as an interpreter. The two men failed in their mission to find the Emperor of China but did visit a native Taíno village. There they were the first to observe the smoking of tobacco, a habit which they promptly picked up.

Third Landfall: Hispaniola

Leaving Cuba, Columbus made landfall on the Island of Hispaniola on December 5. Indigenous people called it Haití but Columbus referred to it as La Española, a name which was later changed to Hispaniola when Latin texts were written about the discovery. On December 25, the Santa María ran aground and had to be abandoned. Columbus himself took over as captain of the Niña, as the Pinta had become separated from the other two ships. Negotiating with the local chieftain Guacanagari, Columbus arranged to leave 39 of his men behind in a small settlement, named La Navidad .

Return to Spain

On January 6, the Pinta arrived, and the ships were reunited: they set out for Spain on January 16. The ships arrived in Lisbon, Portugal, on March 4, returning to Spain shortly after that.

Historical Importance of Columbus' First Voyage

In retrospect, it is somewhat surprising that what is today considered one of the most important voyages in history was something of a failure at the time. Columbus had promised to find a new, quicker route to the lucrative Chinese trade markets and he failed miserably. Instead of holds full of Chinese silks and spices, he returned with some trinkets and a few bedraggled Indigenous people from Hispaniola. Some 10 more had perished on the voyage. Also, he had lost the largest of the three ships entrusted to him.

Columbus actually considered the Indigenous people his greatest find. He thought that a new trade of enslaved people could make his discoveries lucrative. Columbus was hugely disappointed a few years later when Queen Isabela, after careful thought, decided not to open the New World to the trading of enslaved people.

Columbus never believed that he had found something new. He maintained, to his dying day, that the lands he discovered were indeed part of the known Far East. In spite of the failure of the first expedition to find spices or gold, a much larger second expedition was approved, perhaps in part due to Columbus’ skills as a salesman.

Herring, Hubert. A History of Latin America From the Beginnings to the Present. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1962

Thomas, Hugh. "Rivers of Gold: The Rise of the Spanish Empire, from Columbus to Magellan." 1st edition, Random House, June 1, 2004.

- Biography of Christopher Columbus

- La Navidad: First European Settlement in the Americas

- Biography of Christopher Columbus, Italian Explorer

- The Third Voyage of Christopher Columbus

- The Second Voyage of Christopher Columbus

- 10 Facts About Christopher Columbus

- The Truth About Christopher Columbus

- The Fourth Voyage of Christopher Columbus

- Biography of Juan Ponce de León, Conquistador

- Amerigo Vespucci, Explorer and Navigator

- Where Are the Remains of Christopher Columbus?

- Biography of Diego Velazquez de Cuellar, Conquistador

- The Florida Expeditions of Ponce de Leon

- What Was the Age of Exploration?

- Did Christopher Columbus Actually Discover America?

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

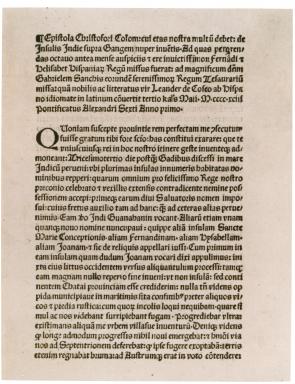

Columbus reports on his first voyage, 1493

A spotlight on a primary source by christopher columbus.

On August 3, 1492, Columbus set sail from Spain to find an all-water route to Asia. On October 12, more than two months later, Columbus landed on an island in the Bahamas that he called San Salvador; the natives called it Guanahani.

For nearly five months, Columbus explored the Caribbean, particularly the islands of Juana (Cuba) and Hispaniola (Santo Domingo), before returning to Spain. He left thirty-nine men to build a settlement called La Navidad in present-day Haiti. He also kidnapped several Native Americans (between ten and twenty-five) to take back to Spain—only eight survived. Columbus brought back small amounts of gold as well as native birds and plants to show the richness of the continent he believed to be Asia.

When Columbus arrived back in Spain on March 15, 1493, he immediately wrote a letter announcing his discoveries to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, who had helped finance his trip. The letter was written in Spanish and sent to Rome, where it was printed in Latin by Stephan Plannck. Plannck mistakenly left Queen Isabella’s name out of the pamphlet’s introduction but quickly realized his error and reprinted the pamphlet a few days later. The copy shown here is the second, corrected edition of the pamphlet.

The Latin printing of this letter announced the existence of the American continent throughout Europe. “I discovered many islands inhabited by numerous people. I took possession of all of them for our most fortunate King by making public proclamation and unfurling his standard, no one making any resistance,” Columbus wrote.

In addition to announcing his momentous discovery, Columbus’s letter also provides observations of the native people’s culture and lack of weapons, noting that “they are destitute of arms, which are entirely unknown to them, and for which they are not adapted; not on account of any bodily deformity, for they are well made, but because they are timid and full of terror.” Writing that the natives are “fearful and timid . . . guileless and honest,” Columbus declares that the land could easily be conquered by Spain, and the natives “might become Christians and inclined to love our King and Queen and Princes and all the people of Spain.”

An English translation of this document is available.

I have determined to write you this letter to inform you of everything that has been done and discovered in this voyage of mine.

On the thirty-third day after leaving Cadiz I came into the Indian Sea, where I discovered many islands inhabited by numerous people. I took possession of all of them for our most fortunate King by making public proclamation and unfurling his standard, no one making any resistance. The island called Juana, as well as the others in its neighborhood, is exceedingly fertile. It has numerous harbors on all sides, very safe and wide, above comparison with any I have ever seen. Through it flow many very broad and health-giving rivers; and there are in it numerous very lofty mountains. All these island are very beautiful, and of quite different shapes; easy to be traversed, and full of the greatest variety of trees reaching to the stars. . . .

In the island, which I have said before was called Hispana , there are very lofty and beautiful mountains, great farms, groves and fields, most fertile both for cultivation and for pasturage, and well adapted for constructing buildings. The convenience of the harbors in this island, and the excellence of the rivers, in volume and salubrity, surpass human belief, unless on should see them. In it the trees, pasture-lands and fruits different much from those of Juana. Besides, this Hispana abounds in various kinds of species, gold and metals. The inhabitants . . . are all, as I said before, unprovided with any sort of iron, and they are destitute of arms, which are entirely unknown to them, and for which they are not adapted; not on account of any bodily deformity, for they are well made, but because they are timid and full of terror. . . . But when they see that they are safe, and all fear is banished, they are very guileless and honest, and very liberal of all they have. No one refuses the asker anything that he possesses; on the contrary they themselves invite us to ask for it. They manifest the greatest affection towards all of us, exchanging valuable things for trifles, content with the very least thing or nothing at all. . . . I gave them many beautiful and pleasing things, which I had brought with me, for no return whatever, in order to win their affection, and that they might become Christians and inclined to love our King and Queen and Princes and all the people of Spain; and that they might be eager to search for and gather and give to us what they abound in and we greatly need.

Questions for Discussion

Read the document introduction and transcript in order to answer these questions.

- Columbus described the Natives he first encountered as “timid and full of fear.” Why did he then capture some Natives and bring them aboard his ships?

- Imagine the thoughts of the Europeans as they first saw land in the “New World.” What do you think would have been their most immediate impression? Explain your answer.

- Which of the items Columbus described would have been of most interest to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella? Why?

- Why did Columbus describe the islands and their inhabitants in great detail?

- It is said that this voyage opened the period of the “Columbian Exchange.” Why do you think that term has been attached to this period of time?

A printer-friendly version is available here .

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter..

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

Did This Map Guide Columbus?

Researchers decipher a mystifying 15th-century document

Elizabeth Quill

The map itself is undated, but there are clues it was created in 1491: It quotes a book published that year, and Christopher Columbus may have consulted the map (or a copy) before his great voyage. When he landed in the Bahamas, he thought he was close to Japan, an error consistent with Japan’s location on the map, which depicts Asia, Africa and Europe but not, alas, the Americas. The map, made by a German working in Florence named Henricus Martellus, has long been overlooked because fading obscured much of its text. Until now.

A new analysis reveals hundreds of place names and 60 written passages, a novel view of Renaissance cartography. “It’s a missing link in our understanding of people’s conception of the world,” says Chet Van Duzer, an independent historian who led the analysis of the map, currently held at Yale University’s Beinecke Library. Martellus relied on Claudius Ptolemy’s projections and then updated them with more recent discoveries—including details from Marco Polo’s voyages and the Portuguese trips around the Cape of Good Hope. The famous Waldseemuller map, which in 1507 depicted the Americas for the first time, appears to have borrowed heavily from Martellus.

To see the writing, researchers photographed the 6- by 4-foot map under 12 frequencies of light, from ultraviolet to infrared. Advanced imaging tools and layering techniques provided the necessary clarity. Below are examples of analyzed map images as viewed at different frequencies, and above is the map itself, with touch points identifying text uncovered by Van Duzer and his colleagues.

Related Reads

The Map Thief: The Gripping Story of an Esteemed Rare-Map Dealer

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

Elizabeth Quill | READ MORE

Elizabeth Quill is a senior editor for Smithsonian magazine.

Category : Maps of voyages by Christopher Columbus

Media in category "maps of voyages by christopher columbus".

The following 74 files are in this category, out of 74 total.

- Maps of voyages

- Christopher Columbus

- Maps showing 15th-century history

- Maps showing 16th-century history

- North America in the 15th century

- North America in the 16th century

- Maps of Spanish trade routes

- Maps of crossings of the Atlantic Ocean

- Atlantic Ocean in the 15th century

- Atlantic Ocean in the 16th century

- Uses of Wikidata Infobox

- Uses of Wikidata Infobox with no image

Navigation menu

- Try for free

Chart Columbus's Voyages

- Students will be able to map out Columbus's four voyages.

- Students will create a key for a map

- A map of the world for each student

- Colored pencils

- Copies of the following handouts: Columbus's Voyages Just Where Was Columbus?

- Distribute the world maps and colored pencils to each students.

- What were Columbus's intended destinations for each voyage?

- Why was he trying to get to each destination?

- Where is Europe?

- Where is Asia?

- Where is North America?

- Where is South America?

- Have students plot each of Columbus's voyages in a different color.

- Students can make a key to indicate the meaning of each color.

- For extra credit ask students to calculate the distance (using the scale) that Columbus traveled on each voyage.

Featured Middle School Resources

Related Resources

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Voyages of Christopher Columbus. Between 1492 and 1504, the Italian navigator and explorer Christopher Columbus led four transatlantic maritime expeditions in the name of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain to the Caribbean and to Central and South America. These voyages led to the widespread knowledge of the New World.

Click on the world map to view an example of the explorer's voyage. How to Use the Map. After opening the map, click the icon to expand voyage information. You can view each voyage individually or all at once by clicking on the to check or uncheck the voyage information. Click on either the map icons or on the location name in the expanded ...

The explorer Christopher Columbus made four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean from Spain: in 1492, 1493, 1498 and 1502. His most famous was his first voyage, commanding the ships the Nina, the ...

This 1491 map is the best surviving map of the world as Christopher Columbus knew it as he made his first voyage across the Atlantic. In fact, Columbus likely used a copy of it in planning his ...

Christopher Columbus (born between August 26 and October 31?, 1451, Genoa [Italy]—died May 20, 1506, Valladolid, Spain) was a master navigator and admiral whose four transatlantic voyages (1492-93, 1493-96, 1498-1500, and 1502-04) opened the way for European exploration, exploitation, and colonization of the Americas. He has long been called the "discoverer" of the New World ...

Voyages Principal Voyage Columbus' voyage departed in August of 1492 with 87 men sailing on three ships: the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María. Columbus commanded the Santa María, while the Niña was led by Vicente Yanez Pinzon and the Pinta by Martin Pinzon. 3 This was the first of his four trips. He headed west from Spain across the ...

Columbus Christopher (c. 1451 - 20 May 1506) A Genoese navigator, colonizer, and explorer, who in total had four transatlantic navigations, among which the most well-known voyage was the first ...

Christopher Columbus was an Italian explorer credited with the discovery of the Americas in 1492, but Leif Eiriksson had explored the North American continent centuries before Columbus set foot on ...

Map of A map of the North Atlantic showing the routes, directions, and dates of the four voyages of Columbus, from 1492 to 1503. This map is color-coded to show the territories in Africa, South America, and Atlantic islands claimed by the Portuguese, and territories in the West Indies, South America, and Atlantic islands claimed by the Spanish.

Christopher Columbus - Explorer, Voyages, New World: The ships for the first voyage—the Niña, Pinta, and Santa María—were fitted out at Palos, on the Tinto River in Spain. Consortia put together by a royal treasury official and composed mainly of Genoese and Florentine bankers in Sevilla (Seville) provided at least 1,140,000 maravedis to outfit the expedition, and Columbus supplied more ...

Christopher Columbus (/ k ə ˈ l ʌ m b ə s /; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 - 20 May 1506) was an Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed four Spanish-based voyages across the Atlantic Ocean sponsored by the Catholic Monarchs, opening the way for the widespread European exploration and European colonization of the Americas.

Columbus' journeys, by contrast, opened the way for later European expeditions, but he himself never claimed to have discovered America. The story of his "discovery of America" was established and first celebrated in A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus by the American author Washington Irving (l. 1783-1859 CE) published in 1828 CE and this narrative (largely fictional ...

In 1492, Christopher Columbus began his voyage to The Indies; instead, he went to the islands of the Bahamas, naming them "Hispaniola"

Christopher Columbus - Exploration, Caribbean, Americas: The gold, parrots, spices, and human captives Columbus displayed for his sovereigns at Barcelona convinced all of the need for a rapid second voyage. Columbus was now at the height of his popularity, and he led at least 17 ships out from Cádiz on September 25, 1493. Colonization and Christian evangelization were openly included this ...

On October 12, Rodrigo de Triana, a sailor aboard the Pinta, first sighted land. Columbus himself later claimed that he had seen a sort of light or aura before Triana did, allowing him to keep the reward he had promised to give to whoever spotted land first. The land turned out to be a small island in the present-day Bahamas.

Christopher Columbus is one of the most significant figures in all of World History and is particularly important to major world events such as the Age of Exploration and Renaissance.His four famous journeys to the New World in the late 15th century and early 16th century altered the history of the world and led to a mass migration of people from the Old World to the New World.

Animated Maps of the first expeditions to the Americas in the Age of Discovery | From Christopher Columbus to Gonçalo Coelho | 1492 - 1502 | Christopher Co...

Columbus reports on his first voyage, 1493. A Spotlight on a Primary Source by Christopher Columbus. On August 3, 1492, Columbus set sail from Spain to find an all-water route to Asia. On October 12, more than two months later, Columbus landed on an island in the Bahamas that he called San Salvador; the natives called it Guanahani.

The map itself is undated, but there are clues it was created in 1491: It quotes a book published that year, and Christopher Columbus may have consulted the map (or a copy) before his great voyage ...

Chart of Suggested Landfall of Christopher Columbus Becher 1856.jpg 10,375 × 6,817; 27.17 MB. Christopher Colombus first voyage 1492-1493 map-fr.svg 1,922 × 1,256; 399 KB. Christopher Colombus second voyage 1493-1496 map-fr.svg 1,922 × 1,256; 399 KB. Christopher Colombus third voyage 1498-1500 map-fr.svg 1,922 × 1,256; 399 KB.

Summarize This Article The fourth voyage and final years of Christopher Columbus. The winter and spring of 1501-02 were exceedingly busy. The four chosen ships were bought, fitted, and crewed, and some 20 of Columbus's extant letters and memoranda were written then, many in exculpation of Bobadilla's charges, others pressing even harder the nearness of the Earthly Paradise and the need ...

Oct 15, 2023 3:30 AM EDT. Columbus's first voyage to America included three ships, the Pinta, the Nina and Santa Maria. Madrid Marine Museum. A Man for the Ages. When the adventures of Christopher Columbus are studied, the main focus undoubtedly rests on his maiden voyage that occurred in the fall of 1492. The importance of this venture still ...

Have students plot each of Columbus's voyages in a different color. Students can make a key to indicate the meaning of each color. For extra credit ask students to calculate the distance (using the scale) that Columbus traveled on each voyage. Students plot the course of Columbus's various expeditions on a map of the world.