- Dictionaries home

- American English

- Collocations

- German-English

- Grammar home

- Practical English Usage

- Learn & Practise Grammar (Beta)

- Word Lists home

- My Word Lists

- Recent additions

- Resources home

- Text Checker

Definition of trek verb from the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary

- I hate having to trek up that hill with all the groceries.

- Finally, we trekked across the wet sands towards the camp.

Definitions on the go

Look up any word in the dictionary offline, anytime, anywhere with the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary app.

Other results

Nearby words.

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of trek in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- walk The baby has just learned to walk.

- stride She strode purposefully up to the desk and demanded to speak to the manager.

- march He marched right in to the office and demanded to see the governor.

- stroll We strolled along the beach.

- wander She wandered from room to room, not sure of what she was looking for.

- amble She ambled down the street, looking in shop windows.

- backpacking

- bushwalking

- footslogging

- hoof it idiom

- ultra-distance

You can also find related words, phrases, and synonyms in the topics:

trek | Intermediate English

Examples of trek, translations of trek.

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

left luggage

a special room or other place at a station, airport, etc. where bags can be left safely for a short time until they are needed

Simply the best! (Ways to describe the best)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English Verb Noun

- Translations

- All translations

To add trek to a word list please sign up or log in.

Add trek to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Definition of trek

(Entry 1 of 2)

intransitive verb

Definition of trek (Entry 2 of 2)

- peregrinate

- peregrination

Examples of trek in a Sentence

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'trek.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Afrikaans, from Dutch trecken to pull, haul, migrate; akin to Old High German trechan to pull

Afrikaans, from Dutch treck pull, haul, from trecken

1835, in the meaning defined at sense 2

1849, in the meaning defined at sense 2

Dictionary Entries Near trek

Treitz's muscle

Cite this Entry

“Trek.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/trek. Accessed 18 Aug. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of trek.

Kids Definition of trek (Entry 2 of 2)

from Afrikaans trek, "to travel by ox wagon," from Dutch trecken "to haul, pull"

More from Merriam-Webster on trek

Nglish: Translation of trek for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of trek for Arabic Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

Plural and possessive names: a guide, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, 8 words for lesser-known musical instruments, it's a scorcher words for the summer heat, 7 shakespearean insults to make life more interesting, 10 words from taylor swift songs (merriam's version), 9 superb owl words, games & quizzes.

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement

verb (used without object)

He managed to escape from a Siberian labor camp and trekked to Iran, a three-year journey.

He's trekked through the Himalayas and summited Mt. Kilimanjaro.

We trekked back to our hotel in the pouring rain.

- South Africa. to travel by ox wagon.

verb (used with object)

- South Africa. (of a draft animal) to draw (a vehicle or load).

- a slow or difficult journey, hike, or trip.

- a migration or expedition, especially by ox wagon.

- a stage of such a journey, between one stopping place and the next.

- a long and often difficult journey

- a journey or stage of a journey, esp a migration by ox wagon

- intr to make a trek

- tr (of an ox, etc) to draw (a load)

Derived Forms

- ˈtrekker , noun

Other Words From

- un·trekked adjective

Word History and Origins

Origin of trek 1

Example Sentences

Writer Leath Tonino devised a 200-mile solo desert trek, following the path of the legendary cartographer who literally put these contentious canyons on the map.

So, we just made the decision to continue on with the trek, but to do it as conscientiously and as low-impact as possible.

He says that the team was able to show microbes would be able to survive the trek from Mars to Earth without shielding from the dangers of space if they clump together.

During their latest trek they checked these survey stakes and determined the speed with which the ice masses creep.

Until now, measuring these effects has required arduous treks through trackless swamps.

During his trek, Brinsley twice passed within a block of a police stationhouse and he almost certainly saw cops along the way.

The audience--tout Hollywood--stands to cheer his slow and painful trek from the wings to the table.

Overall, few travelers have made the trek into the desert of Sudan to see these architectural wonders.

In fact, some feminist critics have pointed to a long history of objectification in Star Trek.

Horst Ulrich, a 72-year-old German on a trek with a group of friends, watched four Nepali guides swept away by an avalanche.

If his partner's impedimentia was not too bulky, the ancient model was ready for another trek to the hills.

The mountaineers, indeed, suffered less than the townsfolk as being more accustomed than they to conditions of trek and battle.

The cool morning air made it bearable for man and beast to trek.

By the third day of their trek southward along the Great River, the soles of Redbird's moccasins had worn through.

Once more was there a cracking of whips, and the oxen, straightening out along the trek-touw (Note 3), moved reluctantly on.

Related Words

Definition of 'trek'

trek in British English

Trek in american english, examples of 'trek' in a sentence trek, cobuild collocations trek, trends of trek.

View usage for: All Years Last 10 years Last 50 years Last 100 years Last 300 years

Browse alphabetically trek

- All ENGLISH words that begin with 'T'

Related terms of trek

- arduous trek

- mountain trek

- the Great Trek

- View more related words

Wordle Helper

Scrabble Tools

Quick word challenge

Quiz Review

Score: 0 / 5

- Access the entire site, including the Easy Learning Grammar , and our language quizzes.

- Customize your language settings. (Unregistered users can only access the International English interface for some pages.)

- Submit new words and phrases to the dictionary.

- Benefit from an increased character limit in our Translator tool.

- Receive our weekly newsletter with the latest news, exclusive content, and offers.

- Be the first to enjoy new tools and features.

- It is easy and completely free !

Create an account

Start your adventure today.

Already a member? Login

Hiking vs Trekking: So Is There Really a Difference?

Quick navigation, define hiking and trekking, what do hiking and trekking actually mean, hiking vs trekking: comparison, equipment differences hiking vs trekking, hiking and trekking benefits, recommended hikes, recommended treks, geographic variations, frequently asked questions about hiking and trekking, final thoughts on hiking vs trekking, join our newsletter.

Get a weekly dose of discounts and inspiration for adventure lovers

Getting out to explore the natural beauty of the outdoors is a popular pastime in many parts of the world and there is no better way to do it than with your own two feet. Hiking and trekking are two different terms that are often used synonymously to describe the act of stepping out onto the trails for a fun journey in a new or familiar setting, but what are the actual differences between hiking vs trekking?

At first glance, the terms hiking and trekking may seem indistinguishable, but on further investigation there are subtle nuances that make each a distinct experience with its own unique circumstances, requirements, and preparations. Continue reading to learn more about the similarities and differences between hiking versus trekking, while gaining some inspiration for your next big outdoor adventure.

To fully understand the difference between hiking vs trekking, the best place to start is with the definition of the terms themselves. The Oxford Dictionary defines the two as:

Hike : a long walk or walking tour.

Trek : a long arduous journey, especially one made on foot.

As you can tell from the definitions above, there is a blurry line between the meaning of hiking and trekking, so how can one better understand the subtle difference between the two?

Firstly, hiking (or walking as it is known in the United Kingdom) is usually used to refer to shorter journeys that are made on foot, usually within the period of 1 day. These adventures can range in length and difficulty, from a brisk countryside walks to gruelling mountain adventures that can take 10+ hours. Usually done for exercise, leisure, or to reconnect with nature, a hike generally follows established footpaths and trails. How each hiker will prepare for their adventure can be equally varied, as challenging terrain or inclement weather might require specialized footwear or gear; however, you will need to pack less (and lighter weight) gear and supplies for a single day hiking excursion when compared to trekking.

While it is not the focus of this comparison, backpacking is a sort of bridge between hiking and trekking, and as such, deserves a quick mention here. More closely related to hiking, backpacking can easily be thought of as a multi-day hiking expedition, where you will need to plan out several overnight camping stays and carry the appropriate gear with you as you hike.

So if hiking is a single day adventure and backpacking covers multiple days, what exactly is trekking in simple terms? Essentially, trekking is a longer, more difficult journey that is undertaken on foot, traversing both on and off-trail terrain. Trekking expeditions are often highly organized and require a good deal of preparation, as the locations can be very remote and the distances covered are far greater. It is not uncommon for a trekking expedition to be stretched over 6, 10, or even 20 days. As you could imagine, such a lengthy undertaking requires trekkers to carry a heavy load of equipment and supplies through rugged terrain, making physical fitness a necessity in order to safely traverse the route.

Friends hiking resting on rock lookout watching the sunset

Trekking gear Gregory backpack hiking poles

Even with a basic understanding of what hiking and trekking are, it can still be a challenge to fully nail down the specifics of what makes each of these outdoor activities unique. Beyond the overall length and level of physical exertion required to complete each task, there are a number of subtle nuances to each that range from gear and supplies to organization and planning. Let’s dive into the similarities and differences between hiking versus trekking.

Hiking vs Trekking Similarities

The similarities between hiking and trekking stem from their shared goal: getting out to explore the natural world on foot. The sole reason for setting out on either type of adventure is up to the individual traveller; however, the things experienced along the way (ie. sightseeing, wildlife watching, etc.) are more or less the same. Pleasure, both in appreciating nature and getting in some good exercise, is one of the main attractions to both hiking and trekking.

Hiking vs Trekking Differences

Whereas similarities between hiking and trekking may be more subtle, the differences are a bit more distinct. The overall length of the journey - usually within 1 day for hiking and multiple days for trekking - and remote nature of the landscape are two of the differentiating factors. Hiking trails will often be very distinct, whereas trekking routes will utilize trails and open or difficult to navigate terrain.

Additionally, trekking generally requires sturdier gear to handle the rigors of successive days of use. Not only this, but trekkers need to account for higher quantities of gear and supplies to support life on the trail.

Aside from the gear aspect, planning and logistics are also more of a factor when comparing trekking to hiking. You will need to meticulously plan for all eventualities along the trail, and the remote nature of the route will likely require extra time and planning to reach. Due to all of this, a trekking expedition is often a much more serious undertaking that will require added time, money, and organization in order to successfully execute when compared to a hiking excursion.

Hiking toward mountians with camera

Couple with backpacks walking through the forest toward cabin

Arguably one of the biggest differences when it comes to comparing hiking versus trekking is in the gear. Trekking generally covers much longer distances and a longer period of time; the result of which is a need for more and sturdier gear. As the main focus of either activity is walking, you will need to ensure that you choose the right pair of footwear . Depending on the terrain and length of the hike, you will likely be able to get away with a lighter pair of hiking boots or trail runners. By comparison, a longer and more serious trek will require sturdier boots with a thicker sole and good ankle support. Two other critical pieces of equipment that you will need for either type of journey are a compass and a first aid kit that contains a variety of supplies to keep you safe on the trail.

When setting out for a hiking excursion, there are some essential pieces of gear that you will need in order to safely, comfortably, and successfully traverse the trail. You will want your gear to be fairly lightweight, but still cover you for every eventuality. As such, be sure to bring a lightweight day pack to carry everything. Obviously food and a large water bottle will be critical in keeping you fueled along the route, but spare socks and extra layers will aid you if you run into any inclement weather. Hiking poles are also a great idea to provide extra stability, especially if you will be traversing uneven ground.

In regards to preparing for a trekking expedition, much of the same advice above applies, except for the fact that you will be spending more time along the trail. Make sure to choose your gear wisely, as remote areas will limit your ability to head back to the trailhead in the event that you run into some trouble. A few things to consider:

-In order to carry your extra gear and supplies, you will need a larger pack, ideally one that is 60L.

-Sleeping along the trail will require a tent, sleeping pad, and sleeping bag.

-Bring extra clothing to stay dry and warm for the duration of your trip.

-You will need more than just a day's worth of water. Think about bringing a water filtration or purification system, as lugging around bottles of water will create unnecessary weight.

-Lastly, you will need extra food supplies, as well as cookware, fuel, and a camp stove to cook on.

While it may seem like a lot to arrange, all of the extra items that are required for a trekking expedition when compared to a day hike really do reflect the fundamental difference between the two activities, namely that trekking is a much longer, arduous, and serious affair that will require extra organization and planning.

Trekking group backpackers walking through misty foggy forest

So, if hiking and trekking are such physically demanding activities, why are they good for you? As with many different outdoor activities, hiking and trekking both offer a number of great benefits to your health that are the result of putting the different systems of your body to work. The most obvious are the physical benefits; however, lesser-known are the impact that they have on other aspects of your wellbeing, such as mental and social health.

Prolonged periods of physical activity that feature natural intervals (think climbing and descending hills) offer a great number of health benefits. Such activities can help with weight loss, reducing the risk of stroke, and general body maintenance. As weight bearing exercises, hiking and trekking will also serve to build bone density, strengthen muscles in the core and lower half of the body, as well as build endurance levels.

In terms of mental health, the exposure to vitamin D that comes with outdoor exercise can also provide a mental boost, increasing your creative capabilities and clearing your mind.

A 2015 study from Stanford University found that increased exposure to the outdoors resulted in less activity in the parts of the brain that are associated with mental illness. As such, many people find that feelings of anxiety, stress and depression can be alleviated through hiking and trekking, as they are able to detach from the worries of the outside world and connect with nature. This focus on the beauty of what is in front of you will allow you to come up with problem solving strategies that will help you in your everyday life.

Lastly, and closely related to the mental health points above, hiking and trekking will help you to form better social connections. Hitting the trails with friends, family, or even new acquaintances is a great way to bond and learn about one another in a new setting that is removed from the outside world. Even setting out for a solo adventure has its benefits in this regard, as some alone time is often a great way to alter your perspective and grow as a person, so that you can strengthen your relationships with others.

Regardless of your intentions when setting out on a hiking or trekking expedition, the benefits to your physical, mental, and social health are an undeniably positive byproduct that will certainly serve you well in your everyday life.

Mountain top ridge walk climbing rocky peak above the clouds

Group of women hiking Helvellyn Walk UK

No matter where you find yourself in the world, you will almost always be in close proximity to a hiking route of some form or another that will enable you to get out and enjoy the beauty of nature, while getting some decent exercise in the process. Whether you plan on exploring the countryside around your hometown or are travelling further afield, there are a number of fantastic hiking routes that are suitable for a wide range of ages and skill levels.

For anyone making their way through the picturesque landscapes of Europe, the Matterhorn Glacier Trail in Switzerland offers a chance to explore the stunning terrain of the Alps, while the Lago di Carezza is a charming hike to a gorgeous lake that is set within the Dolomite Mountains of Italy. Similarly, the Helvellyn Walk is a rugged adventure in the United Kingdom that will showcase the natural beauty of the Lake District.

For those adventurers looking to explore North America, the crystal clear waters and rugged mountain peaks within Banff National Park, Alberta can be experienced along the Skoki Lakes Hike , while the winding rivers and breathtaking canyons of Zion National Park, Utah can be witnessed along the Angel’s Landing Hike .

These are just a few of the popular and awe-inspiring routes that can be found around the globe; however, there are countless other hiking regions that are ready and waiting to be explored, so why not strap on your boots and get ready to hit the trails!

Hiker standing on top of tall rock peak looking out to mountains

Friends with backpacks camping gear hiking with dogs

Similarly to the many amazing hiking routes that can be found worldwide, there are countless treks around the globe that are set within near-magical locations, featuring famously scenic landscapes and world-renowned highlights. While there is generally a good variety of hiking routes for all skill levels, the challenging nature of most treks limit their usage to more experienced outdoor enthusiasts that are familiar with navigating remote and rugged landscapes or to those willing to hire a guide.

Known for the mountainous terrain of the Andes and the fascinating culture of the Quechua people, the Inca Trail Trek to Machu Picchu is a fantastic trek that will lead you up to this world famous mountain top historical site on an adventure that sounds like the inspiration for an adventure novel. Similarly, the Picos de Europa Mountain Trek is a stunning 12-day journey through the mountains of Picos de Europa National Park that will allow you to take in the picturesque landscapes of northern Spain, while the Grand Yosemite Traverse Tour With Horsepack Support is a fun way to explore the gorgeous terrain within the most well-known national park in the United States.

For anyone looking to explore some of the most iconic mountain landscapes in the world, the Mount Kilimanjaro Northern Circuit Route is a breathtaking 8-day journey to the summit of the highest mountain in Africa, whereas the Annapurna Base Camp Trek will see you experience the jaw-dropping panoramic views of Nepal’s Himalayas on a 16-day adventure near the top of the world.

While these examples of famous treks will require you to travel around the world in order to begin your adventure, they - and countless other treks - can also serve as a source of inspiration for you to plan your own multi-day trek somewhere nearby.

Lac Blanc, Chamonix, France

Lago di Carezza, Nova Levante BZ, Italia

It’s safe to say that there are a fair number of similarities and differences that can be seen when comparing hiking vs trekking; however, there are also some geographic variations in the naming of each activity that can make distinguishing the two even more confusing. Here are a few alternate terms that are used around the world to describe hiking and trekking:

Walking: As mentioned above, any journey in the United Kingdom that is made on foot is referred to as walking, whether it is a quick stroll to the shops or a lengthy adventure into the mountains.

Bush Walking: Used throughout Australia, bush walking is a term that is interchangeable with hiking.

Tramping: A term only used in New Zealand, tramping is more akin to trekking than it is hiking, as the distances are often longer and the terrain is more rugged and remote. Tramping is also sometimes used when referring to a particularly long or difficult day walk; however, it is mostly reserved for multi-day treks and the region’s famous “Great Walks”, such as the Kepler Track, Abel Tasman Coast Track, and the world famous Te Araroa Trail .

Rambling, Hillwalking, Fellwalking: At one time used in various regions of the United Kingdom, these terms are now largely used by older generations, as they reflect the terminology from a previous era of outdoor exploration and invoke nostalgia.

Mountaineers hiking trekking walking with poles in low light

Inca Trail trek in Peru leads to Macchu Pichu ancient stone village

Is hiking better than walking?

While the question is fairly subjective, the simplest answer is yes. Hiking will burn more calories than walking.

Is trekking more difficult than hiking?

Yes… sometimes. Trekking often involves covering greater distances, over a longer period, in more remote and difficult terrain; however, an extreme day-hike through technically challenging terrain that features a large elevation gain can be equally difficult.

Man with backpack and camping gear standing above canyon

Steam rising from small pot on camp stove backcountry camp kitchen

How do you prepare for a hiking or trekking excursion?

Strength, cardio, and endurance training are all great ways to prepare for a hiking or trekking excursion. Check out these training guides for hiking trips and longer backpacking trips to get started.

Is it OK to hike every day?

Yes… depending on how strenuous of a hike it is. Anything in excess is ill-advised, so if you plan on hiking daily, try mixing in some low-intensity hikes to allow your body to rest.

Family crossing river along hiking walking trail

Sunrise sunset camping gear tent on mountain top lookout

Is hiking good for losing weight?

Hiking is a great cardio workout that will help you to burn calories and lose weight, although per half hour it will burn less than running.

Does hiking tone your body?

Similar to using a stair climber in the gym, uphill hiking will help to build muscle; however, the downhill portion is what will tone your muscles the most, as your glutes and quads will be working in overdrive to help stabilize your body.

Hiking boots on mossy rocks crossing stream creek

In short, although the definitions of hiking and trekking may be nearly indistinguishable, there are similarities and differences that make these two outdoor activities unique, yet closely related. At the base level, the easiest way to distinguish between hiking versus trekking is the overall length of time needed to complete the activity, with hiking being the shorter of the two.

It is up to the individual to explore the subtle nuances of each in order to fully understand which type of excursion best suits their needs. Whether you are looking for a life-changing multi-day adventure in some far-off, mythical land or simply to get in better shape while exploring the outdoors, the worlds of hiking and trekking can be found along the same spectrum, and you just might find that your involvement in one will lead you to realize a passion in the other.

Top Destinations

Tour activities, top regions, get travel inspiration and discounts.

Join our weekly travel newsletter

Oxford English Dictionary

Words and phrases, the historical english dictionary.

An unsurpassed guide for researchers in any discipline to the meaning, history, and usage of over 500,000 words and phrases across the English-speaking world.

Understanding entries

Glossaries, abbreviations, pronunciation guides, frequency, symbols, and more

Personal account

Change display settings, save searches and purchase subscriptions

Getting started

Videos and guides about how to use the new OED website

Recently added

- smooth talker

- okonomiyaki

- broken heart

- anti-marketeer

Word of the day

Recently updated.

Word stories

Read our collection of word stories detailing the etymology and semantic development of a wide range of words, including ‘dungarees’, ‘codswallop’, and ‘witch’.

Access our word lists and commentaries on an array of fascinating topics, from film-based coinages to Tex-Mex terms.

World Englishes

Explore our World Englishes hub and access our resources on the varieties of English spoken throughout the world by people of diverse cultural backgrounds.

History of English

Here you can find a series of commentaries on the History of English, charting the history of the English language from Old English to the present day.

- Access or purchase personal subscriptions

- Get our newsletter

- Save searches

- Set display preferences

Institutional access

Sign in with library card

Sign in with username / password

Recommend to your librarian

Institutional account management

Sign in as administrator on Oxford Academic

Word of the Day

Sign up to receive the Oxford English Dictionary Word of the Day email every day.

Our Privacy Policy sets out how Oxford University Press handles your personal information, and your rights to object to your personal information being used for marketing to you or being processed as part of our business activities.

We will only use your personal information for providing you with this service.

1849, in a South African context, "a stage of a journey by ox wagon;" from Afrikaans trek , "a journey or migration; distance between one place and the next; action of drawing" a vehicle, as an ox; from Dutch trekken "to march, journey," originally "to draw, pull," from Middle Dutch trecken , which probably is related to the source of track (n.).

Historically, especially in reference to the Groot Trek (1835 and after) of more than 10,000 Boers, who, discontented with the English colonial authorities, left Cape Colony and went north and north-east. In general use in English as a noun, "long journey or toilsome expedition," by 1941.

by 1850, in a South African context, "to travel or migrate by ox wagon," from Afrikaans, from Dutch trekken "to march, journey," originally "to draw, pull" (a vehicle, as an ox), from Middle Dutch trecken , which probably is related to the source of track (n.). Also compare trek (n.). By 1911 in the general sense of "make a long journey or toilsome expedition." Related: Trekked ; trekking .

Entries linking to trek

late 15c., trak , "footprint, mark left by anything" (originally of a horse or horses, in Malory), from Old French trac "track of horses, trace" (mid-15c.), a word of uncertain origin. According to OED (1989) "generally thought to be" from a Germanic source (compare Middle Low German treck , Dutch trek "drawing, pulling") and thus from the source of trek (q.v.). Also compare the sense development of trace (v.)).

The meaning "two continuous lines of rails for drawing trains" is attested by 1805. Expression wrong side of the tracks "bad part of town" is by 1901, American English.

As "place where races are run, course laid out and prepared for racing" by 1827. The meaning "branch of athletics involving a running course" is recorded from 1905. Track-suit is by 1896.

The meaning "single recorded item" is from 1904, originally in reference to phonograph records. The meaning "mark on skin from repeated drug injection" is attested by 1964.

US colloquial in one's tracks "where one stands" is by 1824. To make tracks "move or go quickly" is American English colloquial attested by 1819. To be on track "doing what is required or expected" is by 1973. To cover (one's) tracks in the figurative sense (like a pursued animal) is attested by 1898.

In later figurative uses the sense of following game and railroading might both be present: To be off the track usually was "derailed." To be on (or off ) the right track is by 1795; to lose track is by 1894; to keep track of (something) is attested by 1837.

Track lighting is attested by that name from 1970, in reference to the fittings that slide in grooves.

Track record (1955) is a figurative use from racing, "performance history" of an individual car, runner, horse, etc. (1907), but the phrase was more common earlier in the sense "fastest speed recorded at a particular track."

"one who treks; traveler, wanderer, migrator," 1851, agent noun from trek (v.) or from Dutch trekker .

- See all related words ( 4 ) >

Trends of trek

More to explore.

updated on June 27, 2024

Trending words

- 1 . longevity

- 3 . sandwich

- 4 . canoodle

- 7 . pharmacy

- 8 . wednesday

- 10 . pregnant

Dictionary entries near trek

- premium features

- pricing - single

- pricing - family

- pricing - organizations

- the invisible cause

- initiatives

-

- LearnThat Foundation

- testimonials

- LearnThatWord and...

- who uses it

- our partners

- Open Dictionary of English

- About the ODE

- word list archive

- English oddities

- How it works - videos

- start student account

- start teacher account

- schools & higher ed

- tutors and IEP

Are you a native English speaker? How do you pronounce this word?

{%type%} Definitions

- no images available

Short "hint"

n. - Any long and difficult trip; A journey by ox wagon (especially an organized migration by a group of settlers) v. - Make a long and difficult journey; Journey on foot, especially in the mountains.

Usage examples (39)

- Joining him on the trek is his pal Katz, a man who at first seems incapable of walking the length of a shopping mall.

- We made the trek from the chapel to the gravesite ....

- Japanese monks begin trek across West to remember nuclear bombings

- Here's a roundup of additional posts on xeni. net/ trek from the past day:

Tutoring comment

Tutoring comment not yet available...

Synonyms (0)

Antonyms (0), rhymes with, conjugation.

- Find us on Google+

- Our LinkedIn group

- Spelling City comparison

- spelling bee

- spelling bee words

- learn English (ELL)

- academic vocabulary/GRE

- TOEFL vocabulary/IELTS

- spelling words

- spelling coaching

- commonly misspelled words

- spelling word list

- spelling games

- tutoring partners

LearnThatWord and the Open Dictionary of English are programs by LearnThat Foundation, a 501(c)3 nonprofit.

Questions? Feedback? We want to hear from you! Email us or click here for instant support .

Copyright © 2005 and after - LearnThat Foundation. Patents pending.

Translator for

Lingvanex - your universal translation app, meaning & definition of trek in english, lingvanex products for translation of text, images, voice, documents:, language translation.

Trek Definition and Meaning

Table of Contents

Trek definitions, trek snonyms, trek idioms & phrases, trek through history, a trek of discovery, make the trek, off on a trek, the long trek home, trek for a cause, a trek across continents, a trek to remember, trek into the unknown, embark on a trek, trek with companions, a trek through nature, a trek through time, trek at one's own pace, on the trek, a trek of endurance, trek under the stars, a scenic trek, survive the trek, a solitary trek, trek example sentences, common curiosities, why is it called trek, how many syllables are in trek, how do we divide trek into syllables, how is trek used in a sentence, what is the root word of trek, what part of speech is trek, what is a stressed syllable in trek, what is the verb form of trek, what is the third form of trek, what is the pronunciation of trek, what is the second form of trek, is trek a noun or adjective, what is the singular form of trek, what is the opposite of trek, is trek an adverb, is trek a collective noun, is the word trek a gerund, which vowel is used before trek, what is the first form of trek, what is the plural form of trek, is trek an abstract noun, is trek a negative or positive word, is trek a countable noun, which preposition is used with trek, is the trek term a metaphor, is the word trek imperative, which determiner is used with trek, which conjunction is used with trek, which article is used with trek, what is another term for trek, is trek a vowel or consonant, is the word “trek” a direct object or an indirect object, share your discovery.

Author Spotlight

Popular Terms

Trending Comparisons

- ABBREVIATIONS

- BIOGRAPHIES

- CALCULATORS

- CONVERSIONS

- DEFINITIONS

Vocabulary

What does TREK mean?

Definitions for trek trɛk trek, this dictionary definitions page includes all the possible meanings, example usage and translations of the word trek ., princeton's wordnet rate this definition: 5.0 / 1 vote.

a journey by ox wagon (especially an organized migration by a group of settlers)

any long and difficult trip

journey on foot, especially in the mountains

"We spent the summer trekking in the foothills of the Himalayas"

make a long and difficult journey

"They trekked towards the North Pole with sleds and skis"

Wiktionary Rate this definition: 4.0 / 1 vote

A slow or difficult journey.

We're planning on going on a trek up Kilimanjaro.

A journey by ox wagon, especially the Boer migration of 1835-7.

To make a slow or arduous journey.

To journey on foot, especially to hike through mountainous areas.

To travel by ox wagon.

Etymology: From trek.

ChatGPT Rate this definition: 0.0 / 0 votes

A trek is a long, arduous journey, typically on foot and often involving challenging terrains such as mountains, forests, or deserts. It is usually undertaken for the purpose of exploration, adventure or achievement, and requires significant physical effort and perseverance.

Chambers 20th Century Dictionary Rate this definition: 0.0 / 0 votes

trek, v.i. to drag a vehicle: to journey by ox-wagon.— n. the distance from one station to another.— n. Trek′ker , a traveller. [Dut. trekken , to draw.]

Editors Contribution Rate this definition: 0.0 / 0 votes

A trust of translation in transposition as a transitive treasure following a life formed echo. 1.) a long arduous journey, esp. one made on foot. A tourist hike. Draw a vehicle or pull a load. Travel constantly from place to place; lead a nomadic life.

I trek the true words of light within my heart through the stars of my mind for growth and understanding.

Etymology: The Mission

Submitted by Tehorah_Elyon on May 23, 2024

Suggested Resources Rate this definition: 0.0 / 0 votes

What does TREK stand for? -- Explore the various meanings for the TREK acronym on the Abbreviations.com website.

Matched Categories

Usage in printed sources from: .

[["1590","2"],["1631","1"],["1644","1"],["1658","1"],["1706","1"],["1725","1"],["1759","1"],["1760","6"],["1774","1"],["1777","1"],["1787","2"],["1788","1"],["1793","1"],["1794","4"],["1795","1"],["1796","2"],["1801","4"],["1803","2"],["1804","7"],["1805","1"],["1806","3"],["1811","1"],["1812","3"],["1813","1"],["1815","3"],["1816","4"],["1818","1"],["1819","1"],["1820","1"],["1822","4"],["1823","1"],["1824","1"],["1825","1"],["1826","2"],["1827","7"],["1828","1"],["1829","2"],["1830","2"],["1832","4"],["1834","1"],["1835","3"],["1838","12"],["1839","17"],["1840","5"],["1842","2"],["1843","4"],["1844","22"],["1845","2"],["1846","10"],["1847","8"],["1848","8"],["1849","18"],["1850","235"],["1851","78"],["1852","64"],["1853","28"],["1854","8"],["1855","68"],["1856","116"],["1857","83"],["1858","6"],["1859","13"],["1860","94"],["1861","23"],["1862","10"],["1863","85"],["1864","171"],["1865","4"],["1866","19"],["1867","4"],["1868","85"],["1869","10"],["1870","98"],["1871","55"],["1872","5"],["1873","29"],["1874","55"],["1875","52"],["1876","38"],["1877","39"],["1878","348"],["1879","91"],["1880","402"],["1881","88"],["1882","126"],["1883","87"],["1884","77"],["1885","115"],["1886","63"],["1887","91"],["1888","240"],["1889","118"],["1890","69"],["1891","77"],["1892","111"],["1893","462"],["1894","192"],["1895","224"],["1896","355"],["1897","320"],["1898","262"],["1899","643"],["1900","1039"],["1901","756"],["1902","921"],["1903","542"],["1904","289"],["1905","387"],["1906","498"],["1907","612"],["1908","447"],["1909","551"],["1910","720"],["1911","505"],["1912","732"],["1913","933"],["1914","899"],["1915","502"],["1916","468"],["1917","448"],["1918","426"],["1919","723"],["1920","1016"],["1921","926"],["1922","626"],["1923","902"],["1924","753"],["1925","923"],["1926","782"],["1927","895"],["1928","1042"],["1929","1053"],["1930","1415"],["1931","1490"],["1932","1181"],["1933","1030"],["1934","1312"],["1935","1661"],["1936","1656"],["1937","2165"],["1938","2010"],["1939","1553"],["1940","1625"],["1941","1560"],["1942","1346"],["1943","1443"],["1944","1419"],["1945","1472"],["1946","1935"],["1947","2021"],["1948","2130"],["1949","2218"],["1950","2222"],["1951","1845"],["1952","2235"],["1953","2202"],["1954","2498"],["1955","2564"],["1956","2705"],["1957","2736"],["1958","2149"],["1959","2412"],["1960","3691"],["1961","3539"],["1962","3318"],["1963","3407"],["1964","3509"],["1965","4194"],["1966","3931"],["1967","4617"],["1968","4526"],["1969","4663"],["1970","4247"],["1971","4318"],["1972","4297"],["1973","4523"],["1974","4728"],["1975","4650"],["1976","4648"],["1977","5502"],["1978","5170"],["1979","5185"],["1980","5518"],["1981","5798"],["1982","6574"],["1983","6177"],["1984","6535"],["1985","7860"],["1986","7757"],["1987","8814"],["1988","8655"],["1989","10071"],["1990","10138"],["1991","11029"],["1992","10981"],["1993","11563"],["1994","13044"],["1995","12316"],["1996","14721"],["1997","16233"],["1998","16609"],["1999","18534"],["2000","20606"],["2001","21221"],["2002","25055"],["2003","27463"],["2004","27251"],["2005","26132"],["2006","25619"],["2007","26065"],["2008","27503"]]

How to pronounce TREK?

Alex US English David US English Mark US English Daniel British Libby British Mia British Karen Australian Hayley Australian Natasha Australian Veena Indian Priya Indian Neerja Indian Zira US English Oliver British Wendy British Fred US English Tessa South African

How to say TREK in sign language?

Chaldean Numerology

The numerical value of TREK in Chaldean Numerology is: 4

Pythagorean Numerology

The numerical value of TREK in Pythagorean Numerology is: 9

Examples of TREK in a Sentence

Simon Pegg :

You have to bring in new people at same time as satisfying the old people or rather the long term fans, and if something becomes too inside, it's not going to let people in and 'Star Trek ' is so inclusive, it's always about bringing people together - that's what the story's about, so it's a balance of filling it with stuff for people that have been there for 50 years and at the same time making it for someone who has zero years of 'Star Trek '.

Isabel May :

I read probably 50 books, and in particular, the ones that I gravitated towards were journals from young women that made the same trek , and it was interesting. I found one in particular, and it was from a young lady who was 17 at the time, very similar in age to the character I play. I took tidbits from that.

Ellen Stofan :

Think about these things you used to see on TV from science fiction, like communicators on Star Trek , well now we actually have them, space exploration pushes us to say 'here's things we've just dreamed about, but we can turn that into reality.'.

Fans saved Star Trek back in the day and they sort of invented fandom and invented conventions, fan conventions so it seems poetic that we end up here on the 50th anniversary so to bring it straight to the fans who have given us our lives and our livelihood, comic Con is the ultimate playground for someone that's a fan boy or girl.

Michael Rubin :

While many in the West might find it enduring that the King is a Trek kie who once even had a Star Trek 'Voyager' cameo, Islamists consider science fiction forbidden because it presumes to know a future that only God can know.

Popularity rank by frequency of use

- ^ Princeton's WordNet http://wordnetweb.princeton.edu/perl/webwn?s=TREK

- ^ Wiktionary https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/TREK

- ^ ChatGPT https://chat.openai.com

- ^ Chambers 20th Century Dictionary https://www.gutenberg.org/files/37683/37683-h/37683-h.htm#:~:text=TREK

- ^ Usage in printed sources https://books.google.com/ngrams/graph?content=TREK

Translations for TREK

From our multilingual translation dictionary.

- رحلة Arabic

- trek Danish

- jornada, emigrar Spanish

- vaeltaa Finnish

- randonnée French

- vándorlás Hungarian

- melakukan perjalanan Indonesian

- tocht Dutch

- trek Norwegian

- wędrówka Polish

- viagem Portuguese

- trek Vietnamese

Word of the Day

Would you like us to send you a free new word definition delivered to your inbox daily.

Please enter your email address:

Citation

Use the citation below to add this definition to your bibliography:.

Style: MLA Chicago APA

"TREK." Definitions.net. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 18 Aug. 2024. < https://www.definitions.net/definition/TREK >.

Discuss these TREK definitions with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe. If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

You need to be logged in to favorite .

Create a new account.

Your name: * Required

Your email address: * Required

Pick a user name: * Required

Username: * Required

Password: * Required

Forgot your password? Retrieve it

Are we missing a good definition for TREK ? Don't keep it to yourself...

Image credit, the web's largest resource for, definitions & translations, a member of the stands4 network, free, no signup required :, add to chrome, add to firefox, browse definitions.net, are you a words master, something (a term or expression or concept) that has a reciprocal relation to something else, Nearby & related entries:.

- treize-vents

- trekker noun

Alternative searches for TREK :

- Search for TREK on Amazon

- Dictionary entries

- Quote, rate & share

- Meaning of treck

treck ( English)

- Archaic form of trek

This is the meaning of trek :

trek ( English)

Origin & history, pronunciation.

- IPA: /tɹɛk/

- Rhymes: -ɛk

- A slow or difficult journey. We're planning on going on a trek up Kilimanjaro.

- ( South Africa ) A journey by ox wagon.

- ( South Africa ) The Boer migration of 1835-1837.

- ( intransitive ) To make a slow or arduous journey .

- 1892 , Robert Louis Stevenson, The Beach of Falesá Before that they had been a good deal on the move, trekking about after the white man, who was one of those rolling stones that keep going round after a soft job.

- ( intransitive ) To journey on foot , especially to hike through mountainous areas .

- ( South Africa ) To travel by ox wagon .

Automatically generated practical examples in English:

GettyDubai makes a great winter sun destination[/caption] And with a flight time of 7 hours, it’s not too much of a treck . The Sun, 12 August 2022

▾ Dictionary entries

Entries where "treck" occurs:

trace : …("to draw"); and Old French traquer ("to chase, hunt, pursue"), from trac ("a track, trace"), from Middle Dutch treck , treke ("a drawing, draft, delineation, feature, expedition"). More at track. Verb trace (third-person singular…

trek : …trek in deze klus — I have no mind to carry out this task journey, migration draught, air current through a chimney. Verb trek Verb form of trekken Verb form of trekken Anagrams rekt trek (French) Noun trek (masc.) (pl. treks) treck …

traquer : traquer (French) Origin & history From Middle French trac, from Old French trac ("a track, trace, a beaten path, course"), from Middle Dutch treck , treke ("a drawing, draft, delineation, feature, train, procession, line or flourish with a pen…

trecking : trecking (English) Verb trecking Present participle of treck

trecked : trecked (English) Verb trecked Simple past tense and past participle of treck

Quote, Rate & Share

Cite this page : "treck" – WordSense Online Dictionary (17th August, 2024) URL: https://www.wordsense.eu/treck/

There are no notes for this entry.

▾ Next

trecke (Central Franconian)

trecked (English)

trecken (Low German)

trecker (English)

treckers (English)

trecking (English)

trecks (English)

▾ About WordSense

▾ references.

The references include Wikipedia, Cambridge Dictionary Online, Oxford English Dictionary, Webster's Dictionary 1913 and others. Details can be found in the individual articles.

▾ License

▾ latest.

How do you spell baranga? , ogenblik , ébène , How do you spell parodising?

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

- Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement

noun as in long journey

Strongest matches

Strong matches

- peregrination

verb as in journey

Weak matches

- be on the move

- be on the trail

- hit the road

Example Sentences

Writer Leath Tonino devised a 200-mile solo desert trek, following the path of the legendary cartographer who literally put these contentious canyons on the map.

So, we just made the decision to continue on with the trek, but to do it as conscientiously and as low-impact as possible.

He says that the team was able to show microbes would be able to survive the trek from Mars to Earth without shielding from the dangers of space if they clump together.

During their latest trek they checked these survey stakes and determined the speed with which the ice masses creep.

Until now, measuring these effects has required arduous treks through trackless swamps.

During his trek, Brinsley twice passed within a block of a police stationhouse and he almost certainly saw cops along the way.

The audience--tout Hollywood--stands to cheer his slow and painful trek from the wings to the table.

Overall, few travelers have made the trek into the desert of Sudan to see these architectural wonders.

In fact, some feminist critics have pointed to a long history of objectification in Star Trek.

Horst Ulrich, a 72-year-old German on a trek with a group of friends, watched four Nepali guides swept away by an avalanche.

If his partner's impedimentia was not too bulky, the ancient model was ready for another trek to the hills.

The mountaineers, indeed, suffered less than the townsfolk as being more accustomed than they to conditions of trek and battle.

The cool morning air made it bearable for man and beast to trek.

By the third day of their trek southward along the Great River, the soles of Redbird's moccasins had worn through.

Once more was there a cracking of whips, and the oxen, straightening out along the trek-touw (Note 3), moved reluctantly on.

Related Words

Words related to trek are not direct synonyms, but are associated with the word trek . Browse related words to learn more about word associations.

verb as in travel across area

- journey over

- pass through

noun as in migration

- colonization

- displacement

- expatriation

- homesteading

- reestablishment

- resettlement

- transplanting

noun as in journey

- pleasure trip

noun as in journey; people on a journey

- exploration

- undertaking

Viewing 5 / 51 related words

From Roget's 21st Century Thesaurus, Third Edition Copyright © 2013 by the Philip Lief Group.

Green Energy

Electrek green energy brief.

- Solar power

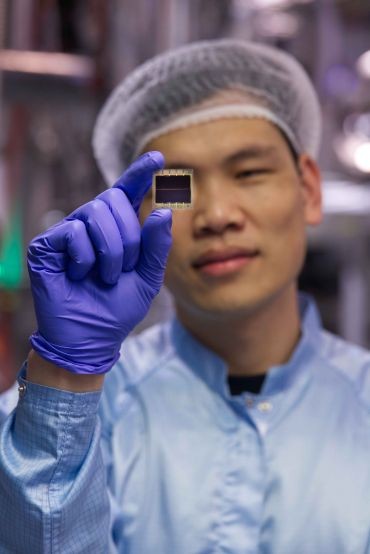

Oxford scientists are generating solar power without panels

Scientists at Oxford University are coating a new solar power-generating material onto objects such as rucksacks, cars, and mobile phones.

The potential of this breakthrough means that increasing amounts of solar electricity could be generated without silicon-based solar panels.

The Oxford scientists’ new light-absorbing material is, for the first time, thin and flexible enough to apply to the surface of almost any building or common object. By stacking multiple light-absorbing layers into one solar cell (known as a multi-junction approach), a wider range of the light spectrum is harnessed, allowing more power to be generated from the same amount of sunlight.

This thin-film perovskite material has been independently certified by Japan’s National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) to deliver over 27% energy efficiency. It matches the performance of traditional, single-layer silicon PV for the first time.

Dr Shuaifeng Hu (pictured), postdoctoral fellow at Oxford University Physics, said:

During just five years of experimenting with our stacking or multi-junction approach, we have raised power conversion efficiency from around 6% to over 27%, close to the limits of what single-layer photovoltaics can achieve today. We believe that, over time, this approach could enable the photovoltaic devices to achieve far greater efficiencies, exceeding 45%.

The versatility of the new ultra-thin and flexible material is also key – at just over one micron thick, it’s almost 150 times thinner than a silicon wafer. Existing photovoltaics are generally applied to silicon panels, but this can be applied to almost any surface.

Dr Junke Wang, Marie Skłodowska Curie Actions postdoc fellow at Oxford University Physics, said:

We can envisage perovskite coatings being applied to broader types of surfaces to generate cheap solar power, such as the roofs of cars and buildings and even the backs of mobile phones. If more solar energy can be generated in this way, we can foresee less need in the longer term to use silicon panels or build more and more solar farms.

The 40 scientists working on photovoltaics at Oxford University Physics Department are led by Professor of Renewable Energy Henry Snaith. Their pioneering work in photovoltaics and especially the use of thin-film perovskite began around a decade ago.

Oxford PV, a UK company spun out of Oxford University Physics in 2010 by Snaith to commercialize perovskite photovoltaics, recently started large-scale manufacturing of perovskite photovoltaics at its factory in Brandenburg-an-der-Havel, near Berlin, Germany. It’s the world’s first volume manufacturing line for “perovskite-on-silicon” tandem solar cells.

Read more: Oxford sets a new world record for solar panel efficiency

To limit power outages and make your home more resilient, consider going solar with a battery storage system. In order to find a trusted, reliable solar installer near you that offers competitive pricing, check out EnergySage , a free service that makes it easy for you to go solar. They have hundreds of pre-vetted solar installers competing for your business, ensuring you get high-quality solutions and save 20-30% compared to going it alone. Plus, it’s free to use and you won’t get sales calls until you select an installer and you share your phone number with them.

Your personalized solar quotes are easy to compare online and you’ll get access to unbiased Energy Advisers to help you every step of the way. Get started here . –trusted affiliate link*

FTC: We use income earning auto affiliate links. More.

Electrek Green Energy Brief: A daily technical, …

Michelle Lewis is a writer and editor on Electrek and an editor on DroneDJ, 9to5Mac, and 9to5Google. She lives in White River Junction, Vermont. She has previously worked for Fast Company, the Guardian, News Deeply, Time, and others. Message Michelle on Twitter or at [email protected]. Check out her personal blog.

Michelle Lewis's favorite gear

MacBook Air

Light, durable, quick: I'll never go back.

Because I don't want to wait for the best of British TV.

Manage push notifications

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- About Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. the wonders of a blockchain, 3. the advantages of database rights for blockchain, 4. the current test for ‘independence’, 5. proposal for a new test for ‘independence’, 6. the place of the ‘content’/’structure’ divide in the broader regime, 7. conclusion.

- < Previous

Blockchain as a database—proposal for a new test for the criterion of ‘independence’ in the legal definition of a database for the purposes of copyright and the sui generis right

Ilsu Erdem Ari has obtained a BA (Hons) in Law at the University of Cambridge (Trinity College) and an LLM at the London School of Economics and Political Science. She recently completed her Bar Vocational Studies at City Law School, which she represented in the Oxford IP Moot 2023 and was a quarterfinalist. She has experience as a Copyright Consultant for the Cambridge Journal of Law, Politics and Art. She has a keen interest in the interaction of IP law with new technologies and has completed the Computer Science for Lawyers course of Harvard Law School Executive Education.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Ilsu Erdem Ari, Blockchain as a database—proposal for a new test for the criterion of ‘independence’ in the legal definition of a database for the purposes of copyright and the sui generis right, Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice , Volume 19, Issue 6, June 2024, Pages 521–540, https://doi.org/10.1093/jiplp/jpae034

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Technology’s exponential growth often outpaces that of the law. The persistence of outdated legal concepts that were not drafted with new technology in mind leads to legal uncertainty. This article focuses on one example of such a friction between old law and new technology, namely the eligibility of blockchain as a‘database’ for protection under the EU Database Directive, as implemented into UK copyright law. The most problematic requirement for blockchain as a candidate is that the material inside the database be ‘independent’. This can pose a significant hurdle for blockchain to succeed as the immutability of blockchain is ensured by the ‘linked-list’ structure in between the blocks and the combinational hashing of data within the individual block. This article examines this issue and proposes a solution to this quandary: to divide the data recorded on a blockchain into ‘content’ and ‘structure’, and confine the criterion of ‘independence’ to the former. In reaching this solution, the author examines previous literature on the different types of data that can be found in databases, as well as how the concept of ‘independence’ is understood by judges and academics. This article will be of practical significance for developers of non-open source blockchain applications who wish to protect their products as a database.

Blockchain technology is one of the most disruptive technologies of Industry 4.0 and its use is no longer limited to private endeavours. 1 The underlying technology is also evolving, with ever-powerful hardware, 2 and blockchain is increasingly marketed as a product. The latest trend is to offer blockchain-as-a-service, which outsources the use of blockchain in a manner akin to ordinary cloud services. 3

Blockchain can certainly protect IP by serving as an immutable register. 4 This debate was revived with the advent of non-fungible tokens (eg regarding whether ‘minting’ is a ‘digital artistic performance’ containing intellectual creativity). 5 If blockchain can protect IP, could IP also protect blockchain? Indeed, if blockchains are increasingly widespread and original in their design, the creators behind these innovations would have an interest in protecting their works from unauthorized reuse.

Blockchain is commonly thought of as a method for securing the storage of data in a decentralized environment, similar to a decentralized database of verified transactions. Over time, our traditional understanding of a ‘database’ as a centralized and paper-based amalgamation of information has morphed into what is now a handy, toolbox-like digital network of data. The protection of databases as IP was significantly enhanced by Directive 96/9/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 1996 on the legal protection of databases (‘Database Directive’). 6 The Database Directive is still relevant post-Brexit. The UK implemented the Database Directive through the Copyright and Rights in Databases Regulations 1997 (‘Database Regulation’). This still has effect today as ‘retained’ EU law, pursuant to section 2(1) of the European Union (EU) (Withdrawal) Act 2018 (EUWA 2018). The High Court of England and Wales, in DRSP Holdings Ltd v O’Connor ( DRSP ), confirmed the Database Regulation along with the relevant Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) and domestic authorities remain good law. 7

The Database Directive grants protection to databases through both copyright (Chapter II of the Database Directive) and a ‘sui generis’ right (Chapter III of the Database Directive), 8 which is a standalone right that is divorced from other regimes. Most interestingly, the Database Directive introduces a new legal definition of what constitutes a ‘database’, which applies to both regimes.

This can be found in Article 1(2) of the Database Directive and, in UK law, undersection 3A(1) of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA 1988). 9

A database can be ‘in any form’ (e.g. in print or electronically), 10 but must adhere to three criteria 11 : (i) a collection of independent works, data or other material (‘independence’), (ii) arranged in a systematic or methodical way (‘systematicity’) and (iii) individually accessible by electronic or other means (‘accessibility’). Out of these, the first criterion is by far the most problematic one for blockchain technology. The immutable quality of data inside the blockchain is attributable to the interdependent nature of the structural data that forms the blocks and the chain in between these blocks.

A strict application of the ‘independence’ criterion would lead to the disqualification of blockchain as a protectable subject matter under the Database Directive. It is argued this stems from the ill-suitedness of current laws to emerging technologies rather than a reasoned and targeted exclusion. It is probable that the legislators in 1996 did not envisage the advent of blockchain technology, which emerged a decade later. As blockchain is a valuable tool in disseminating verified data and developing a competitive information market, it is crucial to examine whether and how current laws can be adapted to this new technology.

This article explores how databases that record both independent and interdependent data like blockchain can be reconciled with the ‘independence’ criterion without contradicting the spirit of the Database Directive. To that end, this article proposes a new three-step legal test for assessing whether a database that includes both types of data can still meet the definition in Article 1(2) of the Database Directive and Section 3A(1) of the CDPA 1988. The functioning of the new test rests on the categorization of the data inside a database into two categories, namely ‘contents’ and ‘structural’ data. ‘Structural’ data inside a blockchain is first and foremost interdependent to ensure the immutability of the recorded data, as well as the systematicity and the accessibility of the blockchain as a whole. By contrast, the independence of its ‘contents’ is fact-sensitive as it depends on the specific application of the blockchain. This article argues the ‘independence’ criterion should only be applied to the latter category instead of the ‘structural’ data that forms the skeleton of the blockchain and guarantees its proper functioning. To inform this discussion, this article undertakes a literature review to examine how ‘independence’ is interpreted and how it is applied to data.

Section 1 briefly outlines the main components of a blockchain that are relevant to the proposal. Section 2 discusses the relevance of the Database Directive to blockchain technology. Section 3 conducts a review of judicial and academic commentary on the ‘independence’ criterion and examines how it fails to accommodate the components of a blockchain as outlined in Section 2 . Section 4 proposes a new legal test for

‘independence’ by relying on the separation of data into ‘content’ and ‘structure’ and applying the ‘independence’ criterion to the latter. Section 5 then places the content’/‘structure’ dichotomy both in the context of Article 1(2) of the Database Directive and section 3A(1) of the CDPA 1988 and of the subsistence tests for copyright and the sui generis right.

The original purpose of a blockchain is to create trust between computer nodes (ie participants to the blockchain) of unknown number and identity in relation to the existence of a state of affairs in the absence of a central authority. 12 This necessity informs how the various components of a blockchain (data structure, software, transaction data, etc) may fail the ‘independence’ criterion.

2.1. How blocks are added

‘Proof-of-work’ (PoW) blockchains will be used as an example here. This does not carry the implication that the proposal cannot apply to other blockchains. The term ‘PoW’ refers to the nature of the method that is agreed between participants of the network (or nodes) as to how a block is to be added. For instance, if members of an organization decide to create a book collection and agree that a new book can only be added if the cover is red, it becomes very easy for members to decide whether a new book should be added or not (as the only criteria they can apply is that of the cover colour).

The criterion PoW employs to decide whether to add a new block is whether sufficient computational power was expanded in adding the block. Such computational power will be accepted as sufficient once a puzzle is solved, which is essentially a mathematical equation that involves finding ‘ x ’ in ‘2 + x = 4’. The solution to the puzzle (ie ‘ x ’) is called the ‘nonce’ (short for ‘number used once’). The difficulty of the puzzle, which is specified inside the block, usually increases with each block that has been added.

The way in which the conditions for finding the nonce are determined (that is how the rest of the equation is decided) depends on the contents of the block itself. 13 By way of example, a transaction is initiated between A and B such that A transfers B 1BTC. These data are pushed onto the network of participants and gathered in a provisional block. The conditions of the equation are then formed depending on data such as the value of the transaction, the parties, the time at which the transaction was initiated and the difficulty level of the puzzle. Once the ‘ x ’ is found by a participant of the network, the rest of the nodes verify the solution and agree on whether the block can be added to the chain permanently. The block is then ‘timestamped’ and receives an identifier number that is unique in the entire chain (called a ‘hash reference’). This identifier can be found in what is the called the block’s header. This can be likened to a document header containing an identifier for the document. The completion of the PoW allows for nodes to establish consensus on the validity of the block. The amount of computational power needed functions as a disincentive to interfere with registered data, since this would require the redoing of that puzzle. What is worth noting is that given the equation’s conditions are dependent on the contents of the provisional block, it also means that the nonce is dependent on the contents of the block.

2.2. How blocks are linked together

A block header only containing its own identifier would be tantamount to a block independently floating inside a blockchain. There are only two solutions to this issue. First, the freshly mined block could include the identifier of the block following it in the chain. This, however, is problematic where adding information to mined blocks or predicting a future block’s identifier is quasi-impossible. The solution is, then, to have each block include the identifier of the previous one. 14 In other words, Block 100 has its own hash reference and the hash reference of Block 99. This ensures that not only 99 follows 100, but also that Block 100 cannot be placed in the chain anywhere but after Block 99 (since otherwise it would be wrong for Block 100’s header to contain Block 99’s identifier).

2.3. How data are rendered immutable

The immutability of data inside and in between blocks is ensured by what is termed as a ‘cryptographic hash function’, which is an encryption method that delivers an output (called a ‘hash string’) in the form of letters and numbers. The hash function in a blockchain produces an encryption that is asymmetric, because running the output of the function back through the function does not yield the original input. Two different functions need to be used to encrypt and decrypt, respectively. This corresponds to the public/private key divide in Bitcoin transactions. Public keys used to encrypt data are accessible by everyone, whereas the corresponding private key is exclusive to the account owner (such that only the intended receiver of the encoded message can decrypt it).

These one-way encryption functions are also ‘collision resistant’ 15 : when the inputs are different, the outputs will also be different (such that the outputs produced will not ‘collide’). These functions are extremely sensitive to changes in the input. For instance, changing a single comma in a 100-page document will yield a completely different hash string. The use of these functions is an effective way of determining whether there has been an attempt to alter data.

The sensitivity of these functions to change is what underlies the immutability of the data inside the blockchain. At a first stage, the raw transactional data (eg ‘A transfers B 1BTC’) is hashed to produce a hash string. The latter output is combined with that of other transactional data and hashed again. This process of combination and hashing is repeated until a single hash string remains. 16 In other words, if there are four pieces of transaction to be recorded in a block (say Ta, Tb, Tc and Td), the hash function will be run twice (to produce Ta-b and Tc-d, and then Ta-b-c-d). The last output will be called the ‘root of the Merkle tree’, where ‘Merkle tree’ refers to the structure of the combinational hashing performed in the block. As such, the root of the Merkle tree is dependent on the contents of the transactional data. If any node attempted to modify either a transaction or an interim hash string, the root of the Merkle tree would be automatically invalidated.

The root of the Merkle tree is then included in the block header and is instrumental in determining what the conditions of the puzzle will be (ie in determining ‘2 + x = 4ʹ). This means that the nonce is also dependent on the root of the Merkle tree and the transactional data recorded within. If anyone attempted to modify any such data in the block header, the nonce and the hash reference of the block itself would be invalidated. All data are essentially ‘locked in’ through one-way, collision-resistant hash functions.

The connection between blocks is ensured by the registering of the hash reference of the previous block in the following one. The hash reference of Block 99 forms the content that goes into the defining of conditions of the puzzle in Block 100. As the hash functions are content-sensitive, the change of a single value in the transactional data in Block 99 will invalidate all subsequent hash references, from Block 100 up until the last block in the chain. Rewriting a blockchain would involve the re-hashing of all such data, which disincentivises such changes and, thus, ensures the immutability of recorded data.

2.4. The types of data inside an individual block

The above demonstrates that a blockchain is in fact a gold mine of different types of data, with each having a different function within the blockchain ecosystem. Overall, it is possible to categorize data inside a single block into two distinct types. The first type of data is application-specific data. The nature of such data depends on the purpose for which the blockchain is being used (eg transactional data for the Bitcoin blockchain to patient data for a medical application). 17

The second type of data is data inherent to the blockchain structure itself, irrespective of the application. This refers to the data necessary to the functioning of the blockchain. Most of this type of data is contained in the block header alongside the block’s identifier in the form of a hash reference. Overall, the block header contains:

(1) a timestamp (denoting when the block is added to the chain), (2) a nonce (solution to the puzzle), (3) the difficulty level (of the puzzle), (4) the root of the Merkle tree of transactional data, (5) the hash reference to the previous block and (6) the version of the software used. 18 The distinction drawn here between the two types of data will be useful to this article’s proposal in classifying data as either ‘content’ or ‘structure’ below.

3.1. The relevance of the Database Directive for blockchain

The Database Directive is the ideal regime for the protection of blockchain-based databases for three reasons. First, the original purpose of blockchain— creating trust over the state of a distributed ledger among untrustworthy nodes— 19 matches the policy objectives underlying the Database Directive. These policy objectives can be gleaned from the Recitals to the Directive: there, databases are described as ‘a vital tool’ in the establishment of an ‘information market’ in light of the ‘exponential growth’ of information generated in today’s world, thereby leading to a need for harmonized regimes for database protection. 20 Protecting these vital tools is crucial where information has become a valuable ‘tradeable commodity’, 21 and where a database’s value largely depends on how ‘comprehensive’ it is in the informational value it harbours. 22

In that regard, the power of blockchain in creating an information market that is accessible worldwide, the veracity of which is mathematically verifiable, is undeniable. Blockchain increases the trustworthy dissemination of information in a market, which is an effective way of achieving the Database Directive’s aim in promoting the free flow of information. 23 The importance of blockchain as a database was particularly emphasized by Finck, who explained that blockchain would lead to ‘a profound paradigm shift regarding data collection, sharing and processing…’. 24 It is unsurprising that blockchain’s use for the secure exchange of information is more widespread than its use for cryptocurrencies. 25

Consequently, it would only benefit jurisdictions to bring blockchain within the ambit of the Database Directive. The blockchain business is particularly profitable—but such profitability depends on the ability of its creators to protect their investment and originality from unauthorized use and distribution. 26 If such a protection is not granted, there risks being a market failure where the billions of dollars invested in blockchain solutions are not met with an equally important protection regime. 27 This risks disincentivizing blockchain creators from investing in jurisdictions where their innovations could go unprotected. This would defeat the purpose of the Database Directive in developing a strong information market in the EU and run counter to financial initiatives like Horizon Europe grants. 28