- Random article

- Teaching guide

- Privacy & cookies

by Chris Woodford . Last updated: July 23, 2023.

Photo: Sound is energy we hear made by things that vibrate. Photo by William R. Goodwin courtesy of US Navy and Wikimedia Commons .

What is sound?

Photo: Sensing with sound: Light doesn't travel well through ocean water: over half the light falling on the sea surface is absorbed within the first meter of water; 100m down and only 1 percent of the surface light remains. That's largely why mighty creatures of the deep rely on sound for communication and navigation. Whales, famously, "talk" to one another across entire ocean basins, while dolphins use sound, like bats, for echolocation. Photo by Bill Thompson courtesy of US Fish and Wildlife Service .

Robert Boyle's classic experiment

Artwork: Robert Boyle's famous experiment with an alarm clock.

How sound travels

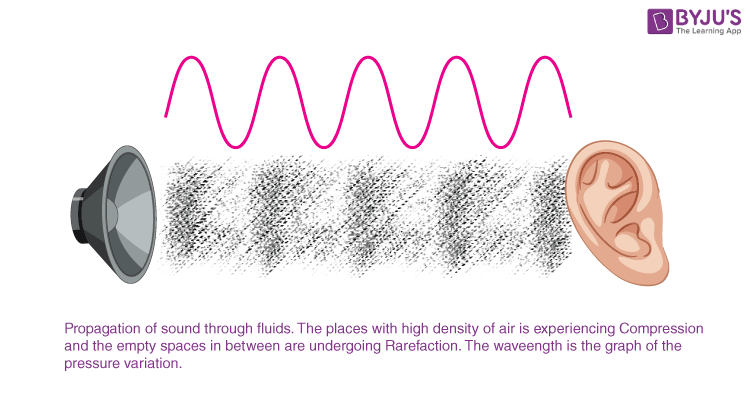

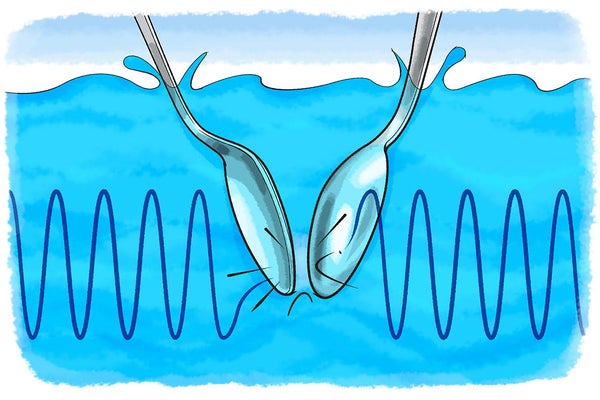

Artwork: Sound waves and ocean waves compared. Top: Sound waves are longitudinal waves: the air moves back and forth along the same line as the wave travels, making alternate patterns of compressions and rarefactions. Bottom: Ocean waves are transverse waves: the water moves back and forth at right angles to the line in which the wave travels.

The science of sound waves

Picture: Reflected sound is extremely useful for "seeing" underwater where light doesn't really travel—that's the basic idea behind sonar. Here's a side-scan sonar (reflected sound) image of a World War II boat wrecked on the seabed. Photo courtesy of U.S. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, US Navy, and Wikimedia Commons .

Whispering galleries and amphitheaters

Photos by Carol M. Highsmith: 1) The Capitol in Washington, DC has a whispering gallery inside its dome. Photo credit: The George F. Landegger Collection of District of Columbia Photographs in Carol M. Highsmith's America, Library of Congress , Prints and Photographs Division. 2) It's easy to hear people talking in the curved memorial amphitheater building at Arlington National Cemetery, Arlington, Virginia. Photo credit: Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress , Prints and Photographs Division.

Measuring waves

Understanding amplitude and frequency, why instruments sound different, the speed of sound.

Photo: Breaking through the sound barrier creates a sonic boom. The mist you can see, which is called a condensation cloud, isn't necessarily caused by an aircraft flying supersonic: it can occur at lower speeds too. It happens because moist air condenses due to the shock waves created by the plane. You might expect the plane to compress the air as it slices through. But the shock waves it generates alternately expand and contract the air, producing both compressions and rarefactions. The rarefactions cause very low pressure and it's these that make moisture in the air condense, producing the cloud you see here. Photo by John Gay courtesy of US Navy and Wikimedia Commons .

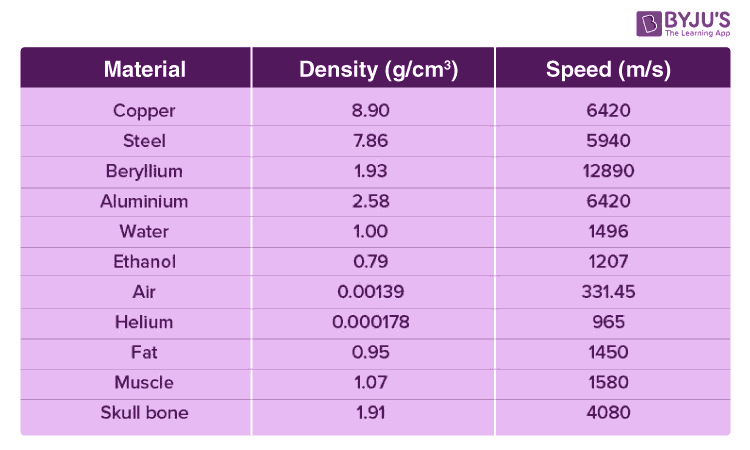

Why does sound go faster in some things than in others?

Chart: Generally, sound travels faster in solids (right) than in liquids (middle) or gases (left)... but there are exceptions!

How to measure the speed of sound

Sound in practice, if you liked this article..., find out more, on this website.

- Electric guitars

- Speech synthesis

- Synthesizers

On other sites

- Explore Sound : A comprehensive educational site from the Acoustical Society of America, with activities for students of all ages.

- Sound Waves : A great collection of interactive science lessons from the University of Salford, which explains what sound waves are and the different ways in which they behave.

Educational books for younger readers

- Sound (Science in a Flash) by Georgia Amson-Bradshaw. Franklin Watts/Hachette, 2020. Simple facts, experiments, and quizzes fill this book; the visually exciting design will appeal to reluctant readers. Also for ages 7–9.

- Sound by Angela Royston. Raintree, 2017. A basic introduction to sound and musical sounds, including simple activities. Ages 7–9.

- Experimenting with Sound Science Projects by Robert Gardner. Enslow Publishers, 2013. A comprehensive 120-page introduction, running through the science of sound in some detail, with plenty of hands-on projects and activities (including welcome coverage of how to run controlled experiments using the scientific method). Ages 9–12.

- Cool Science: Experiments with Sound and Hearing by Chris Woodford. Gareth Stevens Inc, 2010. One of my own books, this is a short introduction to sound through practical activities, for ages 9–12.

- Adventures in Sound with Max Axiom, Super Scientist by Emily Sohn. Capstone, 2007. The original, graphic novel (comic book) format should appeal to reluctant readers. Ages 8–10.

Popular science

- The Sound Book: The Science of the Sonic Wonders of the World by Trevor Cox. W. W. Norton, 2014. An entertaining tour through everyday sound science.

Academic books

- Master Handbook of Acoustics by F. Alton Everest and Ken Pohlmann. McGraw-Hill Education, 2015. A comprehensive reference for undergraduates and sound-design professionals.

- The Science of Sound by Thomas D. Rossing, Paul A. Wheeler, and F. Richard Moore. Pearson, 2013. One of the most popular general undergraduate texts.

Text copyright © Chris Woodford 2009, 2021. All rights reserved. Full copyright notice and terms of use .

Rate this page

Tell your friends, cite this page, can't find what you want search our site below, more to explore on our website....

- Get the book

- Send feedback

- Anatomy & Physiology

- Astrophysics

- Earth Science

- Environmental Science

- Organic Chemistry

- Precalculus

- Trigonometry

- English Grammar

- U.S. History

- World History

... and beyond

- Socratic Meta

- Featured Answers

- Sound waves

Key Questions

Scientifically, this is a very difficult question to answer. The reason is simply that the word "best" is difficult to interpret. In science, understanding the question is often as important as the answer.

You might be asking about the speed of sound. You might be asking about energy loss of sound (e.g. sound traveling through cotton).

Then again, you might be asking about materials which transmit a range of frequencies with very little dispersion (difference between the wave speeds for various pitches). You might look up soliton waves in narrow channels for an example of a wave that stays together over a long distance.

And yet again, you might be asking about materials which can pickup sound from air; an impedance match.

What materials have the highest speed of sound? This is the easiest question to answer, so we'll start with that. In general, the speed of sound in a material varies with the stiffness and mass of that material. Sound traveling through hardened steel will cary much faster than traveling through air. Many materials are characterized by something called a Young's Modulus. You should find that the speed of sound increases with higher Young's Modulus. A search for materials with a high speed of sound or a high Young's Modulus should turn up interesting answers.

One of the most dense materials known is the neutron star. One drop-sized piece of a neutron star has the same mass greater than the giant pyramid at Giza (about a billion tons). Some people calculate the speed of sound in a neutron star to be very close to the speed of light.

- TPC and eLearning

- Read Watch Interact

- What's NEW at TPC?

- Practice Review Test

- Teacher-Tools

- Subscription Selection

- Seat Calculator

- Ad Free Account

- Edit Profile Settings

- Classes (Version 2)

- Student Progress Edit

- Task Properties

- Export Student Progress

- Task, Activities, and Scores

- Metric Conversions Questions

- Metric System Questions

- Metric Estimation Questions

- Significant Digits Questions

- Proportional Reasoning

- Acceleration

- Distance-Displacement

- Dots and Graphs

- Graph That Motion

- Match That Graph

- Name That Motion

- Motion Diagrams

- Pos'n Time Graphs Numerical

- Pos'n Time Graphs Conceptual

- Up And Down - Questions

- Balanced vs. Unbalanced Forces

- Change of State

- Force and Motion

- Mass and Weight

- Match That Free-Body Diagram

- Net Force (and Acceleration) Ranking Tasks

- Newton's Second Law

- Normal Force Card Sort

- Recognizing Forces

- Air Resistance and Skydiving

- Solve It! with Newton's Second Law

- Which One Doesn't Belong?

- Component Addition Questions

- Head-to-Tail Vector Addition

- Projectile Mathematics

- Trajectory - Angle Launched Projectiles

- Trajectory - Horizontally Launched Projectiles

- Vector Addition

- Vector Direction

- Which One Doesn't Belong? Projectile Motion

- Forces in 2-Dimensions

- Being Impulsive About Momentum

- Explosions - Law Breakers

- Hit and Stick Collisions - Law Breakers

- Case Studies: Impulse and Force

- Impulse-Momentum Change Table

- Keeping Track of Momentum - Hit and Stick

- Keeping Track of Momentum - Hit and Bounce

- What's Up (and Down) with KE and PE?

- Energy Conservation Questions

- Energy Dissipation Questions

- Energy Ranking Tasks

- LOL Charts (a.k.a., Energy Bar Charts)

- Match That Bar Chart

- Words and Charts Questions

- Name That Energy

- Stepping Up with PE and KE Questions

- Case Studies - Circular Motion

- Circular Logic

- Forces and Free-Body Diagrams in Circular Motion

- Gravitational Field Strength

- Universal Gravitation

- Angular Position and Displacement

- Linear and Angular Velocity

- Angular Acceleration

- Rotational Inertia

- Balanced vs. Unbalanced Torques

- Getting a Handle on Torque

- Torque-ing About Rotation

- Properties of Matter

- Fluid Pressure

- Buoyant Force

- Sinking, Floating, and Hanging

- Pascal's Principle

- Flow Velocity

- Bernoulli's Principle

- Balloon Interactions

- Charge and Charging

- Charge Interactions

- Charging by Induction

- Conductors and Insulators

- Coulombs Law

- Electric Field

- Electric Field Intensity

- Polarization

- Case Studies: Electric Power

- Know Your Potential

- Light Bulb Anatomy

- I = ∆V/R Equations as a Guide to Thinking

- Parallel Circuits - ∆V = I•R Calculations

- Resistance Ranking Tasks

- Series Circuits - ∆V = I•R Calculations

- Series vs. Parallel Circuits

- Equivalent Resistance

- Period and Frequency of a Pendulum

- Pendulum Motion: Velocity and Force

- Energy of a Pendulum

- Period and Frequency of a Mass on a Spring

- Horizontal Springs: Velocity and Force

- Vertical Springs: Velocity and Force

- Energy of a Mass on a Spring

- Decibel Scale

- Frequency and Period

- Closed-End Air Columns

- Name That Harmonic: Strings

- Rocking the Boat

- Wave Basics

- Matching Pairs: Wave Characteristics

- Wave Interference

- Waves - Case Studies

- Color Addition and Subtraction

- Color Filters

- If This, Then That: Color Subtraction

- Light Intensity

- Color Pigments

- Converging Lenses

- Curved Mirror Images

- Law of Reflection

- Refraction and Lenses

- Total Internal Reflection

- Who Can See Who?

- Formulas and Atom Counting

- Atomic Models

- Bond Polarity

- Entropy Questions

- Cell Voltage Questions

- Heat of Formation Questions

- Reduction Potential Questions

- Oxidation States Questions

- Measuring the Quantity of Heat

- Hess's Law

- Oxidation-Reduction Questions

- Galvanic Cells Questions

- Thermal Stoichiometry

- Molecular Polarity

- Quantum Mechanics

- Balancing Chemical Equations

- Bronsted-Lowry Model of Acids and Bases

- Classification of Matter

- Collision Model of Reaction Rates

- Density Ranking Tasks

- Dissociation Reactions

- Complete Electron Configurations

- Elemental Measures

- Enthalpy Change Questions

- Equilibrium Concept

- Equilibrium Constant Expression

- Equilibrium Calculations - Questions

- Equilibrium ICE Table

- Intermolecular Forces Questions

- Ionic Bonding

- Lewis Electron Dot Structures

- Limiting Reactants

- Line Spectra Questions

- Mass Stoichiometry

- Measurement and Numbers

- Metals, Nonmetals, and Metalloids

- Metric Estimations

- Metric System

- Molarity Ranking Tasks

- Mole Conversions

- Name That Element

- Names to Formulas

- Names to Formulas 2

- Nuclear Decay

- Particles, Words, and Formulas

- Periodic Trends

- Precipitation Reactions and Net Ionic Equations

- Pressure Concepts

- Pressure-Temperature Gas Law

- Pressure-Volume Gas Law

- Chemical Reaction Types

- Significant Digits and Measurement

- States Of Matter Exercise

- Stoichiometry Law Breakers

- Stoichiometry - Math Relationships

- Subatomic Particles

- Spontaneity and Driving Forces

- Gibbs Free Energy

- Volume-Temperature Gas Law

- Acid-Base Properties

- Energy and Chemical Reactions

- Chemical and Physical Properties

- Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion Theory

- Writing Balanced Chemical Equations

- Mission CG1

- Mission CG10

- Mission CG2

- Mission CG3

- Mission CG4

- Mission CG5

- Mission CG6

- Mission CG7

- Mission CG8

- Mission CG9

- Mission EC1

- Mission EC10

- Mission EC11

- Mission EC12

- Mission EC2

- Mission EC3

- Mission EC4

- Mission EC5

- Mission EC6

- Mission EC7

- Mission EC8

- Mission EC9

- Mission RL1

- Mission RL2

- Mission RL3

- Mission RL4

- Mission RL5

- Mission RL6

- Mission KG7

- Mission RL8

- Mission KG9

- Mission RL10

- Mission RL11

- Mission RM1

- Mission RM2

- Mission RM3

- Mission RM4

- Mission RM5

- Mission RM6

- Mission RM8

- Mission RM10

- Mission LC1

- Mission RM11

- Mission LC2

- Mission LC3

- Mission LC4

- Mission LC5

- Mission LC6

- Mission LC8

- Mission SM1

- Mission SM2

- Mission SM3

- Mission SM4

- Mission SM5

- Mission SM6

- Mission SM8

- Mission SM10

- Mission KG10

- Mission SM11

- Mission KG2

- Mission KG3

- Mission KG4

- Mission KG5

- Mission KG6

- Mission KG8

- Mission KG11

- Mission F2D1

- Mission F2D2

- Mission F2D3

- Mission F2D4

- Mission F2D5

- Mission F2D6

- Mission KC1

- Mission KC2

- Mission KC3

- Mission KC4

- Mission KC5

- Mission KC6

- Mission KC7

- Mission KC8

- Mission AAA

- Mission SM9

- Mission LC7

- Mission LC9

- Mission NL1

- Mission NL2

- Mission NL3

- Mission NL4

- Mission NL5

- Mission NL6

- Mission NL7

- Mission NL8

- Mission NL9

- Mission NL10

- Mission NL11

- Mission NL12

- Mission MC1

- Mission MC10

- Mission MC2

- Mission MC3

- Mission MC4

- Mission MC5

- Mission MC6

- Mission MC7

- Mission MC8

- Mission MC9

- Mission RM7

- Mission RM9

- Mission RL7

- Mission RL9

- Mission SM7

- Mission SE1

- Mission SE10

- Mission SE11

- Mission SE12

- Mission SE2

- Mission SE3

- Mission SE4

- Mission SE5

- Mission SE6

- Mission SE7

- Mission SE8

- Mission SE9

- Mission VP1

- Mission VP10

- Mission VP2

- Mission VP3

- Mission VP4

- Mission VP5

- Mission VP6

- Mission VP7

- Mission VP8

- Mission VP9

- Mission WM1

- Mission WM2

- Mission WM3

- Mission WM4

- Mission WM5

- Mission WM6

- Mission WM7

- Mission WM8

- Mission WE1

- Mission WE10

- Mission WE2

- Mission WE3

- Mission WE4

- Mission WE5

- Mission WE6

- Mission WE7

- Mission WE8

- Mission WE9

- Vector Walk Interactive

- Name That Motion Interactive

- Kinematic Graphing 1 Concept Checker

- Kinematic Graphing 2 Concept Checker

- Graph That Motion Interactive

- Two Stage Rocket Interactive

- Rocket Sled Concept Checker

- Force Concept Checker

- Free-Body Diagrams Concept Checker

- Free-Body Diagrams The Sequel Concept Checker

- Skydiving Concept Checker

- Elevator Ride Concept Checker

- Vector Addition Concept Checker

- Vector Walk in Two Dimensions Interactive

- Name That Vector Interactive

- River Boat Simulator Concept Checker

- Projectile Simulator 2 Concept Checker

- Projectile Simulator 3 Concept Checker

- Hit the Target Interactive

- Turd the Target 1 Interactive

- Turd the Target 2 Interactive

- Balance It Interactive

- Go For The Gold Interactive

- Egg Drop Concept Checker

- Fish Catch Concept Checker

- Exploding Carts Concept Checker

- Collision Carts - Inelastic Collisions Concept Checker

- Its All Uphill Concept Checker

- Stopping Distance Concept Checker

- Chart That Motion Interactive

- Roller Coaster Model Concept Checker

- Uniform Circular Motion Concept Checker

- Horizontal Circle Simulation Concept Checker

- Vertical Circle Simulation Concept Checker

- Race Track Concept Checker

- Gravitational Fields Concept Checker

- Orbital Motion Concept Checker

- Angular Acceleration Concept Checker

- Balance Beam Concept Checker

- Torque Balancer Concept Checker

- Aluminum Can Polarization Concept Checker

- Charging Concept Checker

- Name That Charge Simulation

- Coulomb's Law Concept Checker

- Electric Field Lines Concept Checker

- Put the Charge in the Goal Concept Checker

- Circuit Builder Concept Checker (Series Circuits)

- Circuit Builder Concept Checker (Parallel Circuits)

- Circuit Builder Concept Checker (∆V-I-R)

- Circuit Builder Concept Checker (Voltage Drop)

- Equivalent Resistance Interactive

- Pendulum Motion Simulation Concept Checker

- Mass on a Spring Simulation Concept Checker

- Particle Wave Simulation Concept Checker

- Boundary Behavior Simulation Concept Checker

- Slinky Wave Simulator Concept Checker

- Simple Wave Simulator Concept Checker

- Wave Addition Simulation Concept Checker

- Standing Wave Maker Simulation Concept Checker

- Color Addition Concept Checker

- Painting With CMY Concept Checker

- Stage Lighting Concept Checker

- Filtering Away Concept Checker

- InterferencePatterns Concept Checker

- Young's Experiment Interactive

- Plane Mirror Images Interactive

- Who Can See Who Concept Checker

- Optics Bench (Mirrors) Concept Checker

- Name That Image (Mirrors) Interactive

- Refraction Concept Checker

- Total Internal Reflection Concept Checker

- Optics Bench (Lenses) Concept Checker

- Kinematics Preview

- Velocity Time Graphs Preview

- Moving Cart on an Inclined Plane Preview

- Stopping Distance Preview

- Cart, Bricks, and Bands Preview

- Fan Cart Study Preview

- Friction Preview

- Coffee Filter Lab Preview

- Friction, Speed, and Stopping Distance Preview

- Up and Down Preview

- Projectile Range Preview

- Ballistics Preview

- Juggling Preview

- Marshmallow Launcher Preview

- Air Bag Safety Preview

- Colliding Carts Preview

- Collisions Preview

- Engineering Safer Helmets Preview

- Push the Plow Preview

- Its All Uphill Preview

- Energy on an Incline Preview

- Modeling Roller Coasters Preview

- Hot Wheels Stopping Distance Preview

- Ball Bat Collision Preview

- Energy in Fields Preview

- Weightlessness Training Preview

- Roller Coaster Loops Preview

- Universal Gravitation Preview

- Keplers Laws Preview

- Kepler's Third Law Preview

- Charge Interactions Preview

- Sticky Tape Experiments Preview

- Wire Gauge Preview

- Voltage, Current, and Resistance Preview

- Light Bulb Resistance Preview

- Series and Parallel Circuits Preview

- Thermal Equilibrium Preview

- Linear Expansion Preview

- Heating Curves Preview

- Electricity and Magnetism - Part 1 Preview

- Electricity and Magnetism - Part 2 Preview

- Vibrating Mass on a Spring Preview

- Period of a Pendulum Preview

- Wave Speed Preview

- Slinky-Experiments Preview

- Standing Waves in a Rope Preview

- Sound as a Pressure Wave Preview

- DeciBel Scale Preview

- DeciBels, Phons, and Sones Preview

- Sound of Music Preview

- Shedding Light on Light Bulbs Preview

- Models of Light Preview

- Electromagnetic Radiation Preview

- Electromagnetic Spectrum Preview

- EM Wave Communication Preview

- Digitized Data Preview

- Light Intensity Preview

- Concave Mirrors Preview

- Object Image Relations Preview

- Snells Law Preview

- Reflection vs. Transmission Preview

- Magnification Lab Preview

- Reactivity Preview

- Ions and the Periodic Table Preview

- Periodic Trends Preview

- Intermolecular Forces Preview

- Melting Points and Boiling Points Preview

- Reaction Rates Preview

- Ammonia Factory Preview

- Stoichiometry Preview

- Nuclear Chemistry Preview

- Gaining Teacher Access

- Tasks and Classes

- Tasks - Classic

- Subscription

- Subscription Locator

- 1-D Kinematics

- Newton's Laws

- Vectors - Motion and Forces in Two Dimensions

- Momentum and Its Conservation

- Work and Energy

- Circular Motion and Satellite Motion

- Thermal Physics

- Static Electricity

- Electric Circuits

- Vibrations and Waves

- Sound Waves and Music

- Light and Color

- Reflection and Mirrors

- About the Physics Interactives

- Task Tracker

- Usage Policy

- Newtons Laws

- Vectors and Projectiles

- Forces in 2D

- Momentum and Collisions

- Circular and Satellite Motion

- Balance and Rotation

- Electromagnetism

- Waves and Sound

- Atomic Physics

- Forces in Two Dimensions

- Work, Energy, and Power

- Circular Motion and Gravitation

- Sound Waves

- 1-Dimensional Kinematics

- Circular, Satellite, and Rotational Motion

- Einstein's Theory of Special Relativity

- Waves, Sound and Light

- QuickTime Movies

- About the Concept Builders

- Pricing For Schools

- Directions for Version 2

- Measurement and Units

- Relationships and Graphs

- Rotation and Balance

- Vibrational Motion

- Reflection and Refraction

- Teacher Accounts

- Task Tracker Directions

- Kinematic Concepts

- Kinematic Graphing

- Wave Motion

- Sound and Music

- About CalcPad

- 1D Kinematics

- Vectors and Forces in 2D

- Simple Harmonic Motion

- Rotational Kinematics

- Rotation and Torque

- Rotational Dynamics

- Electric Fields, Potential, and Capacitance

- Transient RC Circuits

- Light Waves

- Units and Measurement

- Stoichiometry

- Molarity and Solutions

- Thermal Chemistry

- Acids and Bases

- Kinetics and Equilibrium

- Solution Equilibria

- Oxidation-Reduction

- Nuclear Chemistry

- NGSS Alignments

- 1D-Kinematics

- Projectiles

- Circular Motion

- Magnetism and Electromagnetism

- Graphing Practice

- About the ACT

- ACT Preparation

- For Teachers

- Other Resources

- Newton's Laws of Motion

- Work and Energy Packet

- Static Electricity Review

- Solutions Guide

- Solutions Guide Digital Download

- Motion in One Dimension

- Work, Energy and Power

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Purchasing the Download

- Purchasing the CD

- Purchasing the Digital Download

- About the NGSS Corner

- NGSS Search

- Force and Motion DCIs - High School

- Energy DCIs - High School

- Wave Applications DCIs - High School

- Force and Motion PEs - High School

- Energy PEs - High School

- Wave Applications PEs - High School

- Crosscutting Concepts

- The Practices

- Physics Topics

- NGSS Corner: Activity List

- NGSS Corner: Infographics

- About the Toolkits

- Position-Velocity-Acceleration

- Position-Time Graphs

- Velocity-Time Graphs

- Newton's First Law

- Newton's Second Law

- Newton's Third Law

- Terminal Velocity

- Projectile Motion

- Forces in 2 Dimensions

- Impulse and Momentum Change

- Momentum Conservation

- Work-Energy Fundamentals

- Work-Energy Relationship

- Roller Coaster Physics

- Satellite Motion

- Electric Fields

- Circuit Concepts

- Series Circuits

- Parallel Circuits

- Describing-Waves

- Wave Behavior Toolkit

- Standing Wave Patterns

- Resonating Air Columns

- Wave Model of Light

- Plane Mirrors

- Curved Mirrors

- Teacher Guide

- Using Lab Notebooks

- Current Electricity

- Light Waves and Color

- Reflection and Ray Model of Light

- Refraction and Ray Model of Light

- Classes (Legacy Version)

- Teacher Resources

- Subscriptions

- Newton's Laws

- Einstein's Theory of Special Relativity

- About Concept Checkers

- School Pricing

- Newton's Laws of Motion

- Newton's First Law

- Newton's Third Law

Sound as a Longitudinal Wave

- Sound is a Mechanical Wave

- Sound is a Longitudinal Wave

- Sound is a Pressure Wave

Sound waves in air (and any fluid medium) are longitudinal waves because particles of the medium through which the sound is transported vibrate parallel to the direction that the sound wave moves. A vibrating string can create longitudinal waves as depicted in the animation below. As the vibrating string moves in the forward direction, it begins to push upon surrounding air molecules, moving them to the right towards their nearest neighbor. This causes the air molecules to the right of the string to be compressed into a small region of space. As the vibrating string moves in the reverse direction (leftward), it lowers the pressure of the air immediately to its right, thus causing air molecules to move back leftward. The lower pressure to the right of the string causes air molecules in that region immediately to the right of the string to expand into a large region of space. The back and forth vibration of the string causes individual air molecules (or a layer of air molecules) in the region immediately to the right of the string to continually vibrate back and forth horizontally. The molecules move rightward as the string moves rightward and then leftward as the string moves leftward. These back and forth vibrations are imparted to adjacent neighbors by particle-to-particle interaction. Other surrounding particles begin to move rightward and leftward, thus sending a wave to the right. Since air molecules (the particles of the medium) are moving in a direction that is parallel to the direction that the wave moves, the sound wave is referred to as a longitudinal wave. The result of such longitudinal vibrations is the creation of compressions and rarefactions within the air.

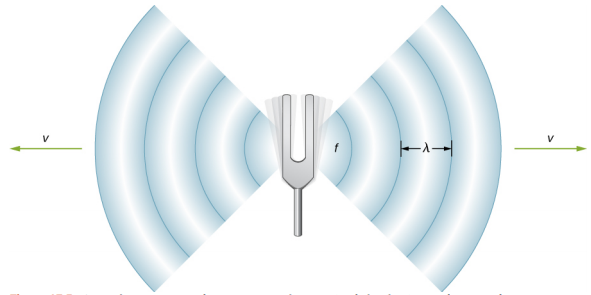

Regardless of the source of the sound wave - whether it is a vibrating string or the vibrating tines of a tuning fork - sound waves traveling through air are longitudinal waves. And the essential characteristic of a longitudinal wave that distinguishes it from other types of waves is that the particles of the medium move in a direction parallel to the direction of energy transport.

We Would Like to Suggest ...

- Pitch and Frequency

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

17.3: Speed of Sound

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 4077

Learning Objectives

- Explain the relationship between wavelength and frequency of sound

- Determine the speed of sound in different media

- Derive the equation for the speed of sound in air

- Determine the speed of sound in air for a given temperature

Sound, like all waves, travels at a certain speed and has the properties of frequency and wavelength. You can observe direct evidence of the speed of sound while watching a fireworks display (Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\)). You see the flash of an explosion well before you hear its sound and possibly feel the pressure wave, implying both that sound travels at a finite speed and that it is much slower than light.

The difference between the speed of light and the speed of sound can also be experienced during an electrical storm. The flash of lighting is often seen before the clap of thunder. You may have heard that if you count the number of seconds between the flash and the sound, you can estimate the distance to the source. Every five seconds converts to about one mile. The velocity of any wave is related to its frequency and wavelength by

\[v = f \lambda, \label{17.3}\]

where \(v\) is the speed of the wave, \(f\) is its frequency, and \(\lambda\) is its wavelength. Recall from Waves that the wavelength is the length of the wave as measured between sequential identical points. For example, for a surface water wave or sinusoidal wave on a string, the wavelength can be measured between any two convenient sequential points with the same height and slope, such as between two sequential crests or two sequential troughs. Similarly, the wavelength of a sound wave is the distance between sequential identical parts of a wave—for example, between sequential compressions (Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\)). The frequency is the same as that of the source and is the number of waves that pass a point per unit time.

Speed of Sound in Various Media

Table \(\PageIndex{1}\) shows that the speed of sound varies greatly in different media. The speed of sound in a medium depends on how quickly vibrational energy can be transferred through the medium. For this reason, the derivation of the speed of sound in a medium depends on the medium and on the state of the medium. In general, the equation for the speed of a mechanical wave in a medium depends on the square root of the restoring force, or the elastic property, divided by the inertial property,

\[v = \sqrt{\frac{\text{elastic property}}{\text{inertial property}}} \ldotp\]

Also, sound waves satisfy the wave equation derived in Waves ,

\[\frac{\partial^{2} y (x,t)}{\partial x^{2}} = \frac{1}{v^{2}} \frac{\partial^{2} y (x,t)}{\partial t^{2}} \ldotp\]

Recall from Waves that the speed of a wave on a string is equal to \(v = \sqrt{\frac{F_{T}}{\mu}}\), where the restoring force is the tension in the string F T and the linear density \(\mu\) is the inertial property. In a fluid, the speed of sound depends on the bulk modulus and the density,

\[v = \sqrt{\frac{B}{\rho}} \ldotp \label{17.4}\]

The speed of sound in a solid the depends on the Young’s modulus of the medium and the density,

\[v = \sqrt{\frac{Y}{\rho}} \ldotp \label{17.5}\]

In an ideal gas (see The Kinetic Theory of Gases ), the equation for the speed of sound is

\[v = \sqrt{\frac{\gamma RT_{K}}{M}}, \label{17.6}\]

where \(\gamma\) is the adiabatic index, R = 8.31 J/mol • K is the gas constant, T K is the absolute temperature in kelvins, and M is the molecular mass. In general, the more rigid (or less compressible) the medium, the faster the speed of sound. This observation is analogous to the fact that the frequency of simple harmonic motion is directly proportional to the stiffness of the oscillating object as measured by k, the spring constant. The greater the density of a medium, the slower the speed of sound. This observation is analogous to the fact that the frequency of a simple harmonic motion is inversely proportional to m, the mass of the oscillating object. The speed of sound in air is low, because air is easily compressible. Because liquids and solids are relatively rigid and very difficult to compress, the speed of sound in such media is generally greater than in gases.

Because the speed of sound depends on the density of the material, and the density depends on the temperature, there is a relationship between the temperature in a given medium and the speed of sound in the medium. For air at sea level, the speed of sound is given by

\[v = 331\; m/s \sqrt{1 + \frac{T_{C}}{273 °C}} = 331\; m/s \sqrt{\frac{T_{K}}{273\; K}} \label{17.7}\]

where the temperature in the first equation (denoted as T C ) is in degrees Celsius and the temperature in the second equation (denoted as T K ) is in kelvins. The speed of sound in gases is related to the average speed of particles in the gas,

\[v_{rms} = \sqrt{\frac{3k_{B}T}{m}}.\]

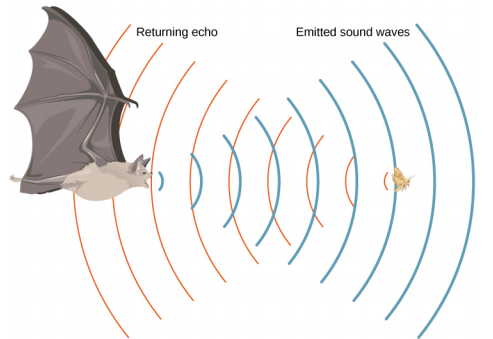

where \(k_B\) is the Boltzmann constant (1.38 x 10 −23 J/K) and m is the mass of each (identical) particle in the gas. Note that v refers to the speed of the coherent propagation of a disturbance (the wave), whereas \(v_{rms}\) describes the speeds of particles in random directions. Thus, it is reasonable that the speed of sound in air and other gases should depend on the square root of temperature. While not negligible, this is not a strong dependence. At 0°C , the speed of sound is 331 m/s, whereas at 20.0 °C, it is 343 m/s, less than a 4% increase. Figure \(\PageIndex{3}\) shows how a bat uses the speed of sound to sense distances.

Derivation of the Speed of Sound in Air

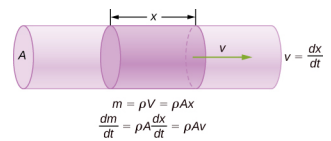

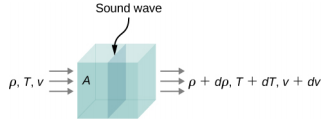

As stated earlier, the speed of sound in a medium depends on the medium and the state of the medium. The derivation of the equation for the speed of sound in air starts with the mass flow rate and continuity equation discussed in Fluid Mechanics . Consider fluid flow through a pipe with cross-sectional area \(A\) (Figure \(\PageIndex{4}\)). The mass in a small volume of length \(x\) of the pipe is equal to the density times the volume, or

\[m = \rho V = \rho Ax.\]

The mass flow rate is

\[\frac{dm}{dt} = \frac{d}{dt} (\rho V) = \frac{d}{dt} (\rho Ax) = \rho A \frac{dx}{dt} = \rho Av \ldotp\]

The continuity equation from Fluid Mechanics states that the mass flow rate into a volume has to equal the mass flow rate out of the volume,

\[\rho_{in} A_{in}v_{in} = \rho_{out} A_{out}v_{out}.\]

Now consider a sound wave moving through a parcel of air. A parcel of air is a small volume of air with imaginary boundaries (Figure \(\PageIndex{5}\)). The density, temperature, and velocity on one side of the volume of the fluid are given as \(\rho\), T, v, and on the other side are \(\rho\) + d\(\rho\), \(T + dT\), \(v + dv\).

The continuity equation states that the mass flow rate entering the volume is equal to the mass flow rate leaving the volume, so

\[\rho Av = (\rho + d \rho)A(v + dv) \ldotp\]

This equation can be simplified, noting that the area cancels and considering that the multiplication of two infinitesimals is approximately equal to zero: d\(\rho\)(dv) ≈ 0,

\[\begin{split} \rho v & = (\rho + d \rho)(v + dv) \\ & = \rho v + \rho (dv) + (d \rho)v + (d \rho)(dv) \\ 0 & = \rho (dv) + (d \rho) v \\ \rho\; dv & = -v\; d \rho \ldotp \end{split}\]

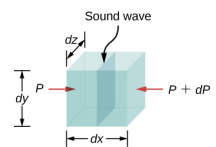

The net force on the volume of fluid (Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\)) equals the sum of the forces on the left face and the right face:

\[\begin{split} F_{net} & = p\; dy\; dz - (p + dp)\; dy\; dz \ & = p\; dy\; dz\; - p\; dy\; dz - dp\; dy\; dz \\ & = -dp\; dy\; dz \\ ma & = -dp\; dy\; dz \ldotp \end{split}\]

Figure \(\PageIndex{6}\):

The acceleration is the force divided by the mass and the mass is equal to the density times the volume, m = \(\rho\)V = \(\rho\) dx dy dz. We have

\[\begin{split} ma & = -dp\; dy\; dz \\ a & = - \frac{dp\; dy\; dz}{m} = - \frac{dp\; dy\; dz}{\rho\; dx\; dy\; dz} = - \frac{dp}{\rho\; dx} \\ \frac{dv}{dt} & = - \frac{dp}{\rho\; dx} \\ dv & = - \frac{dp}{\rho dx} dt = - \frac{dp}{\rho} \frac{1}{v} \\ \rho v\; dv & = -dp \ldotp \end{split}\]

From the continuity equation \(\rho\) dv = −vd\(\rho\), we obtain

\[\begin{split} \rho v\; dv & = -dp \\ (-v\; d \rho)v & = -dp \\ v & = \sqrt{\frac{dp}{d \rho}} \ldotp \end{split}\]

Consider a sound wave moving through air. During the process of compression and expansion of the gas, no heat is added or removed from the system. A process where heat is not added or removed from the system is known as an adiabatic system. Adiabatic processes are covered in detail in The First Law of Thermodynamics , but for now it is sufficient to say that for an adiabatic process, \(pV^{\gamma} = \text{constant}\), where \(p\) is the pressure, \(V\) is the volume, and gamma (\(\gamma\)) is a constant that depends on the gas. For air, \(\gamma\) = 1.40. The density equals the number of moles times the molar mass divided by the volume, so the volume is equal to V = \(\frac{nM}{\rho}\). The number of moles and the molar mass are constant and can be absorbed into the constant p \(\left(\dfrac{1}{\rho}\right)^{\gamma}\) = constant. Taking the natural logarithm of both sides yields ln p − \(\gamma\) ln \(\rho\) = constant. Differentiating with respect to the density, the equation becomes

\[\begin{split} \ln p - \gamma \ln \rho & = constant \\ \frac{d}{d \rho} (\ln p - \gamma \ln \rho) & = \frac{d}{d \rho} (constant) \\ \frac{1}{p} \frac{dp}{d \rho} - \frac{\gamma}{\rho} & = 0 \\ \frac{dp}{d \rho} & = \frac{\gamma p}{\rho} \ldotp \end{split}\]

If the air can be considered an ideal gas, we can use the ideal gas law:

\[\begin{split} pV & = nRT = \frac{m}{M} RT \\ p & = \frac{m}{V} \frac{RT}{M} = \rho \frac{RT}{M} \ldotp \end{split}\]

Here M is the molar mass of air:

\[\frac{dp}{d \rho} = \frac{\gamma p}{\rho} = \frac{\gamma \left(\rho \frac{RT}{M}\right)}{\rho} = \frac{\gamma RT}{M} \ldotp\]

Since the speed of sound is equal to v = \(\sqrt{\frac{dp}{d \rho}}\), the speed is equal to

\[v = \sqrt{\frac{\gamma RT}{M}} \ldotp\]

Note that the velocity is faster at higher temperatures and slower for heavier gases. For air, \(\gamma\) = 1.4, M = 0.02897 kg/mol, and R = 8.31 J/mol • K. If the temperature is T C = 20 °C (T = 293 K), the speed of sound is v = 343 m/s. The equation for the speed of sound in air v = \(\sqrt{\frac{\gamma RT}{M}}\) can be simplified to give the equation for the speed of sound in air as a function of absolute temperature:

\[\begin{split} v & = \sqrt{\frac{\gamma RT}{M}} \\ & = \sqrt{\frac{\gamma RT}{M} \left(\dfrac{273\; K}{273\; K}\right)} = \sqrt{\frac{(273\; K) \gamma R}{M}} \sqrt{\frac{T}{273\; K}} \\ & \approx 331\; m/s \sqrt{\frac{T}{273\; K}} \ldotp \end{split}\]

One of the more important properties of sound is that its speed is nearly independent of the frequency. This independence is certainly true in open air for sounds in the audible range. If this independence were not true, you would certainly notice it for music played by a marching band in a football stadium, for example. Suppose that high-frequency sounds traveled faster—then the farther you were from the band, the more the sound from the low-pitch instruments would lag that from the high-pitch ones. But the music from all instruments arrives in cadence independent of distance, so all frequencies must travel at nearly the same speed. Recall that

\[v = f \lambda \ldotp\]

In a given medium under fixed conditions, \(v\) is constant, so there is a relationship between \(f\) and \(\lambda\); the higher the frequency, the smaller the wavelength (Figure \(\PageIndex{7}\)).

Example \(\PageIndex{1}\): Calculating Wavelengths

Calculate the wavelengths of sounds at the extremes of the audible range, 20 and 20,000 Hz, in 30.0 °C air. (Assume that the frequency values are accurate to two significant figures.)

To find wavelength from frequency, we can use \(v = f \lambda\).

- Identify knowns. The value for \(v\) is given by \[v = 331\; m/s \sqrt{\frac{T}{273\; K}} \ldotp \nonumber\]

- Convert the temperature into kelvins and then enter the temperature into the equation \[v = 331\; m/s \sqrt{\frac{303\; K}{273\; K}} = 348.7\; m/s \ldotp \nonumber\]

- Solve the relationship between speed and wavelength for \(\lambda\): $$\lambda = \frac{v}{f} \ldotp \nonumber$$

- Enter the speed and the minimum frequency to give the maximum wavelength: \[\lambda_{max} = \frac{348.7\; m/s}{20\; Hz} = 17\; m \ldotp \nonumber\]

- Enter the speed and the maximum frequency to give the minimum wavelength: \[\lambda_{min} = \frac{348.7\; m/s}{20,000\; Hz} = 0.017\; m = 1.7\; cm \ldotp \nonumber\]

Significance

Because the product of \(f\) multiplied by \(\lambda\) equals a constant, the smaller \(f\) is, the larger \(\lambda\) must be, and vice versa.

The speed of sound can change when sound travels from one medium to another, but the frequency usually remains the same. This is similar to the frequency of a wave on a string being equal to the frequency of the force oscillating the string. If \(v\) changes and \(f\) remains the same, then the wavelength \(\lambda\) must change. That is, because \(v = f \lambda\), the higher the speed of a sound, the greater its wavelength for a given frequency.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Imagine you observe two firework shells explode. You hear the explosion of one as soon as you see it. However, you see the other shell for several milliseconds before you hear the explosion. Explain why this is so.

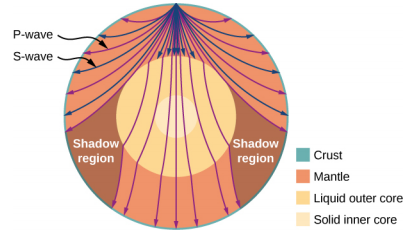

Although sound waves in a fluid are longitudinal, sound waves in a solid travel both as longitudinal waves and transverse waves. Seismic waves, which are essentially sound waves in Earth’s crust produced by earthquakes, are an interesting example of how the speed of sound depends on the rigidity of the medium. Earthquakes produce both longitudinal and transverse waves, and these travel at different speeds. The bulk modulus of granite is greater than its shear modulus. For that reason, the speed of longitudinal or pressure waves (P-waves) in earthquakes in granite is significantly higher than the speed of transverse or shear waves (S-waves). Both types of earthquake waves travel slower in less rigid material, such as sediments. P-waves have speeds of 4 to 7 km/s, and S-waves range in speed from 2 to 5 km/s, both being faster in more rigid material. The P-wave gets progressively farther ahead of the S-wave as they travel through Earth’s crust. The time between the P- and S-waves is routinely used to determine the distance to their source, the epicenter of the earthquake. Because S-waves do not pass through the liquid core, two shadow regions are produced (Figure \(\PageIndex{8}\)).

As sound waves move away from a speaker, or away from the epicenter of an earthquake, their power per unit area decreases. This is why the sound is very loud near a speaker and becomes less loud as you move away from the speaker. This also explains why there can be an extreme amount of damage at the epicenter of an earthquake but only tremors are felt in areas far from the epicenter. The power per unit area is known as the intensity, and in the next section, we will discuss how the intensity depends on the distance from the source.

13.1 Types of Waves

Section learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following:

- Define mechanical waves and medium, and relate the two

- Distinguish a pulse wave from a periodic wave

- Distinguish a longitudinal wave from a transverse wave and give examples of such waves

Teacher Support

The learning objectives in this section will help your students master the following standards:

- (A) examine and describe oscillatory motion and wave propagation in various types of media.

Section Key Terms

Mechanical waves.

What do we mean when we say something is a wave? A wave is a disturbance that travels or propagates from the place where it was created. Waves transfer energy from one place to another, but they do not necessarily transfer any mass. Light, sound, and waves in the ocean are common examples of waves. Sound and water waves are mechanical waves ; meaning, they require a medium to travel through. The medium may be a solid, a liquid, or a gas, and the speed of the wave depends on the material properties of the medium through which it is traveling. However, light is not a mechanical wave; it can travel through a vacuum such as the empty parts of outer space.

A familiar wave that you can easily imagine is the water wave. For water waves, the disturbance is in the surface of the water, an example of which is the disturbance created by a rock thrown into a pond or by a swimmer splashing the water surface repeatedly. For sound waves, the disturbance is caused by a change in air pressure, an example of which is when the oscillating cone inside a speaker creates a disturbance. For earthquakes, there are several types of disturbances, which include the disturbance of Earth’s surface itself and the pressure disturbances under the surface. Even radio waves are most easily understood using an analogy with water waves. Because water waves are common and visible, visualizing water waves may help you in studying other types of waves, especially those that are not visible.

Water waves have characteristics common to all waves, such as amplitude , period , frequency , and energy , which we will discuss in the next section.

Misconception Alert

Many people think that water waves push water from one direction to another. In reality, however, the particles of water tend to stay in one location only, except for moving up and down due to the energy in the wave. The energy moves forward through the water, but the water particles stay in one place. If you feel yourself being pushed in an ocean, what you feel is the energy of the wave, not the rush of water. If you put a cork in water that has waves, you will see that the water mostly moves it up and down.

[BL] [OL] [AL] Ask students to give examples of mechanical and nonmechanical waves.

Pulse Waves and Periodic Waves

If you drop a pebble into the water, only a few waves may be generated before the disturbance dies down, whereas in a wave pool, the waves are continuous. A pulse wave is a sudden disturbance in which only one wave or a few waves are generated, such as in the example of the pebble. Thunder and explosions also create pulse waves. A periodic wave repeats the same oscillation for several cycles, such as in the case of the wave pool, and is associated with simple harmonic motion. Each particle in the medium experiences simple harmonic motion in periodic waves by moving back and forth periodically through the same positions.

[BL] Any kind of wave, whether mechanical or nonmechanical, or transverse or longitudinal, can be in the form of a pulse wave or a periodic wave.

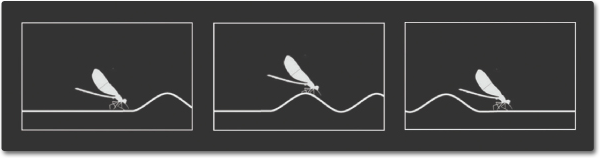

Consider the simplified water wave in Figure 13.2 . This wave is an up-and-down disturbance of the water surface, characterized by a sine wave pattern. The uppermost position is called the crest and the lowest is the trough . It causes a seagull to move up and down in simple harmonic motion as the wave crests and troughs pass under the bird.

Longitudinal Waves and Transverse Waves

Mechanical waves are categorized by their type of motion and fall into any of two categories: transverse or longitudinal. Note that both transverse and longitudinal waves can be periodic. A transverse wave propagates so that the disturbance is perpendicular to the direction of propagation. An example of a transverse wave is shown in Figure 13.3 , where a woman moves a toy spring up and down, generating waves that propagate away from herself in the horizontal direction while disturbing the toy spring in the vertical direction.

In contrast, in a longitudinal wave , the disturbance is parallel to the direction of propagation. Figure 13.4 shows an example of a longitudinal wave, where the woman now creates a disturbance in the horizontal direction—which is the same direction as the wave propagation—by stretching and then compressing the toy spring.

Tips For Success

Longitudinal waves are sometimes called compression waves or compressional waves , and transverse waves are sometimes called shear waves .

Teacher Demonstration

Transverse and longitudinal waves may be demonstrated in the class using a spring or a toy spring, as shown in the figures.

Waves may be transverse, longitudinal, or a combination of the two . The waves on the strings of musical instruments are transverse (as shown in Figure 13.5 ), and so are electromagnetic waves, such as visible light. Sound waves in air and water are longitudinal. Their disturbances are periodic variations in pressure that are transmitted in fluids.

Sound in solids can be both longitudinal and transverse. Essentially, water waves are also a combination of transverse and longitudinal components, although the simplified water wave illustrated in Figure 13.2 does not show the longitudinal motion of the bird.

Earthquake waves under Earth’s surface have both longitudinal and transverse components as well. The longitudinal waves in an earthquake are called pressure or P-waves, and the transverse waves are called shear or S-waves. These components have important individual characteristics; for example, they propagate at different speeds. Earthquakes also have surface waves that are similar to surface waves on water.

Energy propagates differently in transverse and longitudinal waves. It is important to know the type of the wave in which energy is propagating to understand how it may affect the materials around it.

Watch Physics

Introduction to waves.

This video explains wave propagation in terms of momentum using an example of a wave moving along a rope. It also covers the differences between transverse and longitudinal waves, and between pulse and periodic waves.

- After a compression wave, some molecules move forward temporarily.

- After a compression wave, some molecules move backward temporarily.

- After a compression wave, some molecules move upward temporarily.

- After a compression wave, some molecules move downward temporarily.

Fun In Physics

The physics of surfing.

Many people enjoy surfing in the ocean. For some surfers, the bigger the wave, the better. In one area off the coast of central California, waves can reach heights of up to 50 feet in certain times of the year ( Figure 13.6 ).

How do waves reach such extreme heights? Other than unusual causes, such as when earthquakes produce tsunami waves, most huge waves are caused simply by interactions between the wind and the surface of the water. The wind pushes up against the surface of the water and transfers energy to the water in the process. The stronger the wind, the more energy transferred. As waves start to form, a larger surface area becomes in contact with the wind, and even more energy is transferred from the wind to the water, thus creating higher waves. Intense storms create the fastest winds, kicking up massive waves that travel out from the origin of the storm. Longer-lasting storms and those storms that affect a larger area of the ocean create the biggest waves since they transfer more energy. The cycle of the tides from the Moon’s gravitational pull also plays a small role in creating waves.

Actual ocean waves are more complicated than the idealized model of the simple transverse wave with a perfect sinusoidal shape. Ocean waves are examples of orbital progressive waves , where water particles at the surface follow a circular path from the crest to the trough of the passing wave, then cycle back again to their original position. This cycle repeats with each passing wave.

As waves reach shore, the water depth decreases and the energy of the wave is compressed into a smaller volume. This creates higher waves—an effect known as shoaling .

Since the water particles along the surface move from the crest to the trough, surfers hitch a ride on the cascading water, gliding along the surface. If ocean waves work exactly like the idealized transverse waves, surfing would be much less exciting as it would simply involve standing on a board that bobs up and down in place, just like the seagull in the previous figure.

Additional information and illustrations about the scientific principles behind surfing can be found in the “Using Science to Surf Better!” video.

- The surfer would move side-to-side/back-and-forth vertically with no horizontal motion.

- The surfer would forward and backward horizontally with no vertical motion.

Check Your Understanding

Use these questions to assess students’ achievement of the section’s Learning Objectives. If students are struggling with a specific objective, these questions will help identify such objective and direct them to the relevant content.

- A wave is a force that propagates from the place where it was created.

- A wave is a disturbance that propagates from the place where it was created.

- A wave is matter that provides volume to an object.

- A wave is matter that provides mass to an object.

- No, electromagnetic waves do not require any medium to propagate.

- No, mechanical waves do not require any medium to propagate.

- Yes, both mechanical and electromagnetic waves require a medium to propagate.

- Yes, all transverse waves require a medium to travel.

- A pulse wave is a sudden disturbance with only one wave generated.

- A pulse wave is a sudden disturbance with only one or a few waves generated.

- A pulse wave is a gradual disturbance with only one or a few waves generated.

- A pulse wave is a gradual disturbance with only one wave generated.

What are the categories of mechanical waves based on the type of motion?

- Both transverse and longitudinal waves

- Only longitudinal waves

- Only transverse waves

- Only surface waves

In which direction do the particles of the medium oscillate in a transverse wave?

- Perpendicular to the direction of propagation of the transverse wave

- Parallel to the direction of propagation of the transverse wave

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute Texas Education Agency (TEA). The original material is available at: https://www.texasgateway.org/book/tea-physics . Changes were made to the original material, including updates to art, structure, and other content updates.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/physics/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Paul Peter Urone, Roger Hinrichs

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Physics

- Publication date: Mar 26, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/physics/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/physics/pages/13-1-types-of-waves

© Jan 19, 2024 Texas Education Agency (TEA). The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

How do sound waves work?

Sound waves are vibrations that can move us, hurt us, and maybe even heal us.

By Brian S. Hawkins | Updated Jun 1, 2023 2:00 PM EDT

We live our entire lives surrounded by them. They slam into us constantly at more than 700 miles per hour, sometimes hurting, sometimes soothing . They have the power to communicate ideas, evoke fond memories, start fights, entertain an audience, scare the heck out of us, or help us fall in love. They can trigger a range of emotions and they even cause physical damage. This reads like something out of science fiction , but what we’re talking about is very much real and already part of our day-to-day lives. They’re sound waves. So, what are sound waves and how do they work?

If you’re not in the industry of audio, you probably don’t think too much about the mechanics of sound. Sure, most people care about how sounds make them feel, but they aren’t as concerned with how the sound actually affects them. Understanding how sound works does have a number of practical applications , however, and you don’t have to be a physicist or engineer to explore this fascinating subject. Here’s a primer on the science of sound to help get you started.

What’s in a wave

When energy moves through a substance such as water or air, it makes a wave. There are two kinds of waves: longitudinal ones and transverse ones. Transverse waves, as NASA notes , are probably what most people think of when they picture waves—like the up-down ripples of a battle rope used to work out. Longitudinal waves are also known as compression waves, and that’s what sound waves are. There’s no perpendicular motion to these, rather, the wave moves in the same direction as the disturbance.

How sound waves work

Sound waves are a type of energy that’s released when an object vibrates. Those acoustic waves travel from their source through air or another medium, and when they come into contact with our eardrums, our brains translate the pressure waves into words, music, or signals we can understand. These pulses help you place where things are in your environment.

We can experience sound waves in ways that are more physical, not just physiological, too. If sound waves reach a microphone —whether it’s a plug-n-play USB livestream mic or a studio-quality microphone for vocals —it transforms them into electronic impulses that are turned back into sound by vibrating speakers . Whether listening at home or at a concert, we can feel the deep bass in our chest. Opera singers can use them to shatter glass. It’s even possible to see sound waves sent through a medium like sand, which leaves behind a kind of sonic footprint.

That shape is rolling peaks and valleys, the signature of a sine (aka sinusoid) wave. If the wave travels faster, those peaks and valleys form closer together. If it moves slower, they spread out. It’s not a poor analogy to think of them somewhat like waves in the ocean. It’s this movement that allows sound waves to do so many other things.

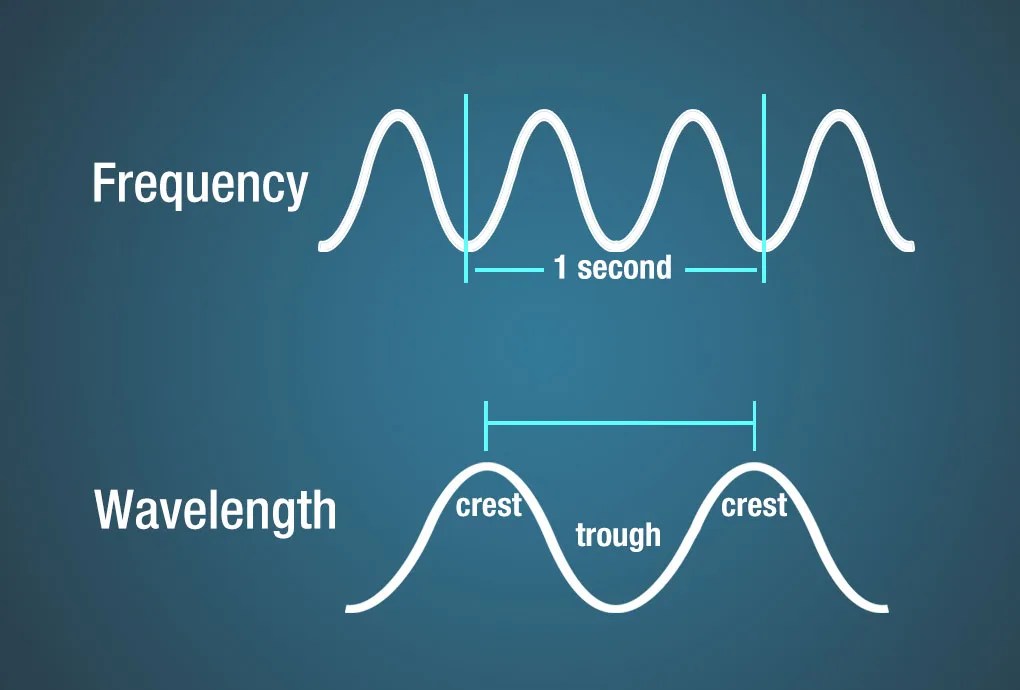

It’s all about frequency

When we talk about a sound wave’s speed, we’re referring to how fast these longitudinal waves move from peak to trough and back to peak. Up … and then down … and then up … and then down. The technical term is frequency , but many of us know it as pitch. We measure sound frequency in hertz (Hz), which represents cycles-per-second, with faster frequencies creating higher-pitched sounds. For instance, the A note right above Middle C on a piano is measured at 440 Hz—it travels up and down at 440 cycles per second. Middle C itself is 261.63 Hz—a lower pitch, vibrating at a slower frequency.

Understanding frequencies can be useful in many ways. You can precisely tune an instrument by analyzing the frequencies of its strings. Recording engineers use their understanding of frequency ranges to dial in equalization settings that help sculpt the sound of the music they’re mixing . Car designers work with frequencies—and materials that can block them—to help make engines quieter. And active noise cancellation uses artificial intelligence and algorithms to measure external frequencies and generate inverse waves to cancel environmental rumble and hum, allowing top-tier ANC headphones and earphones to isolate the wearer from the noise around them. The average frequency range of human hearing is 20 to 20,000 Hz.

What’s in a name?

The hertz measurement is named for the German physicist Heinrich Rudolf Hertz , who proved the existence of electromagnetic waves.

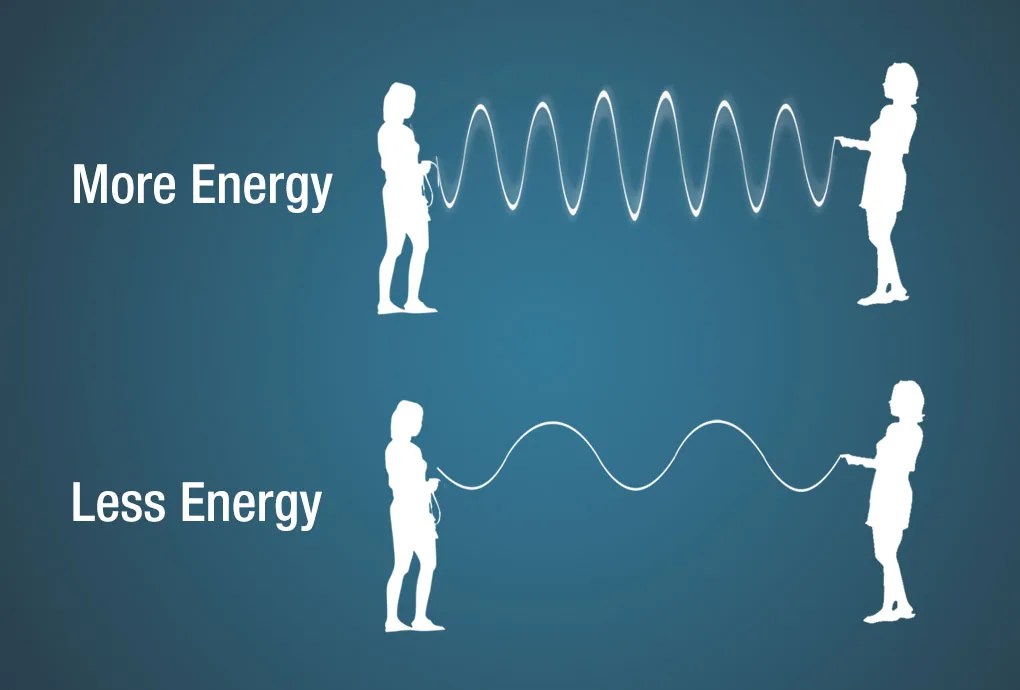

Getting amped

Amplitude equates to sound’s volume or intensity. Using our ocean analogy—because, hey, it works—amplitude describes the height of the waves.

We measure amplitude in decibels (dB). The dB scale is logarithmic, which means there’s a fixed ratio between measurement units. And what does that mean? Let’s say you have a dial on your guitar amp with evenly spaced steps on it numbered one through five. If the knob is following a logarithmic scale, the volume won’t increase evenly as you turn the dial from marker to marker. If the ratio is 4, let’s say, then turning the dial from the first to the second marker increases the sound by 4 dB. But going from the second to the third marker increases it by 16 dB. Turn the dial again and your amp becomes 64 dB louder. Turn it once more, and you’ll blast out a blistering 256 dB—more than loud enough to rupture your eardrums. But if you’re somehow still standing, you can turn that knob one more time to increase your volume to a brain-walloping 1,024 decibels. That’s almost 10 times louder than any rock concert you’ll ever encounter, and it will definitely get you kicked out of your rehearsal space. All of which is why real amps aren’t designed that way.

Twice as nice

We interpret a 10 dB increase in amplitude as a doubling of volume.

Parts of a sound wave

Timbre and envelope are two characteristics of sound waves that help determine why, say, two instruments can play the same chords but sound nothing alike.

Timbre is determined by the unique harmonics formed by the combination of notes in a chord. The A in an A chord is only its fundamental note—you also have overtones and undertones. The way these sound together helps keep a piano from sounding like a guitar, or an angry grizzly bear from sounding like a rumbling tractor engine.

[Related: Even plants pick up on good vibes ]

But we also rely on envelopes, which determine how a sound’s amplitude changes over time. A cello’s note might swell slowly to its maximum volume, then hold for a bit before gently fading out again. On the other hand, a slamming door delivers a quick, sharp, loud sound that cuts off almost instantly. Envelopes comprise four parts: Attack, Decay, Sustain, and Release. In fact, they’re more formally known as ADSR Envelopes.

- Attack: This is how quickly the sound achieves its maximum volume. A barking dog has a very short attack; a rising orchestra has a slower one.

- Decay: This describes how fast the sound settles into its sustained volume. When a guitar player plucks a string , the note starts off loudly but quickly settles into something quieter before fading out completely. The time it takes to hit that sustained volume is decay.

- Sustain: Sustain isn’t a measure of time; it’s a measure of amplitude, or volume. It’s how loud the plucked guitar note is after the initial attack but before it fades out.

- Release: This is the time it takes for the note to drift off to silence.

Speed of sound

Science fiction movies like it when spaceships explode with giant, rumbling, surround-sound booms . However, sound needs to travel through a medium so, despite Hollywood saying otherwise, you’d never hear an explosion in the vacuum of space.

Sound’s velocity , or the speed it travels at , differs depending on the density (and even temperature) of the medium it’s moving through—it’s faster in the air than water, for instance. Generally, sound moves at 1,127 feet per second, or 767.54 miles per hour. When jets break the sound barrier , they’re traveling faster than that. And knowing these numbers lets you estimate the distance of a lightning strike by counting the time between the flash and thunder’s boom—if you count to 10, it’s approximately 11,270 feet away, or about a quarter-mile. (Very roughly, of course.)

A stimulating experience

Anyone can benefit from understanding the fundamentals of sound and what sound waves are. Musicians and content creators with home recording set-ups and studio monitors obviously need a working knowledge of frequencies and amplitude. If you host a podcast, you’ll want as many tools as possible to ensure your voice sounds clear and rich, and this can include understanding the frequencies of your voice, what microphones are best suited to them , and how to set up your room to reflect or dampen the sounds you do or do not want. Having some foundational information is also useful when doing home-improvement projects— when treating a recording workstation , for instance, or just soundproofing a new enclosed deck. And who knows, maybe one day you’ll want to shatter glass. Having a better understanding of the physics of sound opens up wonderful new ways to explore and experience the world around us. Now, go out there and make some noise!

This post has been updated. It was originally published on July 27, 2021.

Brian is a documentary producer, director, and cameraman on feature films and docu-series, and has more than 20 years’ experience as a journalist. He enjoys covering pop-culture, tech, and the conflation of the two.

Like science, tech, and DIY projects?

Sign up to receive Popular Science's emails and get the highlights.

Anatomy of an Electromagnetic Wave

Energy, a measure of the ability to do work, comes in many forms and can transform from one type to another. Examples of stored or potential energy include batteries and water behind a dam. Objects in motion are examples of kinetic energy. Charged particles—such as electrons and protons—create electromagnetic fields when they move, and these fields transport the type of energy we call electromagnetic radiation, or light.

What are Electromagnetic and Mechanical waves?

Mechanical waves and electromagnetic waves are two important ways that energy is transported in the world around us. Waves in water and sound waves in air are two examples of mechanical waves. Mechanical waves are caused by a disturbance or vibration in matter, whether solid, gas, liquid, or plasma. Matter that waves are traveling through is called a medium. Water waves are formed by vibrations in a liquid and sound waves are formed by vibrations in a gas (air). These mechanical waves travel through a medium by causing the molecules to bump into each other, like falling dominoes transferring energy from one to the next. Sound waves cannot travel in the vacuum of space because there is no medium to transmit these mechanical waves.

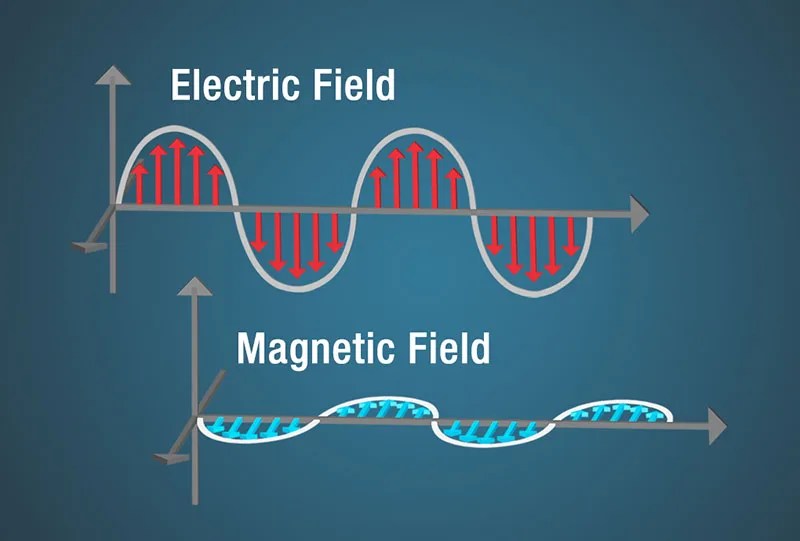

ELECTROMAGNETIC WAVES

Electricity can be static, like the energy that can make your hair stand on end. Magnetism can also be static, as it is in a refrigerator magnet. A changing magnetic field will induce a changing electric field and vice-versa—the two are linked. These changing fields form electromagnetic waves. Electromagnetic waves differ from mechanical waves in that they do not require a medium to propagate. This means that electromagnetic waves can travel not only through air and solid materials, but also through the vacuum of space.

In the 1860's and 1870's, a Scottish scientist named James Clerk Maxwell developed a scientific theory to explain electromagnetic waves. He noticed that electrical fields and magnetic fields can couple together to form electromagnetic waves. He summarized this relationship between electricity and magnetism into what are now referred to as "Maxwell's Equations."

Heinrich Hertz, a German physicist, applied Maxwell's theories to the production and reception of radio waves. The unit of frequency of a radio wave -- one cycle per second -- is named the hertz, in honor of Heinrich Hertz.

His experiment with radio waves solved two problems. First, he had demonstrated in the concrete, what Maxwell had only theorized — that the velocity of radio waves was equal to the velocity of light! This proved that radio waves were a form of light! Second, Hertz found out how to make the electric and magnetic fields detach themselves from wires and go free as Maxwell's waves — electromagnetic waves.

WAVES OR PARTICLES? YES!

Light is made of discrete packets of energy called photons. Photons carry momentum, have no mass, and travel at the speed of light. All light has both particle-like and wave-like properties. How an instrument is designed to sense the light influences which of these properties are observed. An instrument that diffracts light into a spectrum for analysis is an example of observing the wave-like property of light. The particle-like nature of light is observed by detectors used in digital cameras—individual photons liberate electrons that are used for the detection and storage of the image data.

POLARIZATION

One of the physical properties of light is that it can be polarized. Polarization is a measurement of the electromagnetic field's alignment. In the figure above, the electric field (in red) is vertically polarized. Think of a throwing a Frisbee at a picket fence. In one orientation it will pass through, in another it will be rejected. This is similar to how sunglasses are able to eliminate glare by absorbing the polarized portion of the light.

DESCRIBING ELECTROMAGNETIC ENERGY

The terms light, electromagnetic waves, and radiation all refer to the same physical phenomenon: electromagnetic energy. This energy can be described by frequency, wavelength, or energy. All three are related mathematically such that if you know one, you can calculate the other two. Radio and microwaves are usually described in terms of frequency (Hertz), infrared and visible light in terms of wavelength (meters), and x-rays and gamma rays in terms of energy (electron volts). This is a scientific convention that allows the convenient use of units that have numbers that are neither too large nor too small.

The number of crests that pass a given point within one second is described as the frequency of the wave. One wave—or cycle—per second is called a Hertz (Hz), after Heinrich Hertz who established the existence of radio waves. A wave with two cycles that pass a point in one second has a frequency of 2 Hz.

Electromagnetic waves have crests and troughs similar to those of ocean waves. The distance between crests is the wavelength. The shortest wavelengths are just fractions of the size of an atom, while the longest wavelengths scientists currently study can be larger than the diameter of our planet!

An electromagnetic wave can also be described in terms of its energy—in units of measure called electron volts (eV). An electron volt is the amount of kinetic energy needed to move an electron through one volt potential. Moving along the spectrum from long to short wavelengths, energy increases as the wavelength shortens. Consider a jump rope with its ends being pulled up and down. More energy is needed to make the rope have more waves.

Next: Wave Behaviors

National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Science Mission Directorate. (2010). Anatomy of an Electromagnetic Wave. Retrieved [insert date - e.g. August 10, 2016] , from NASA Science website: http://science.nasa.gov/ems/02_anatomy

Science Mission Directorate. "Anatomy of an Electromagnetic Wave" NASA Science . 2010. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. [insert date - e.g. 10 Aug. 2016] http://science.nasa.gov/ems/02_anatomy

Discover More Topics From NASA

James Webb Space Telescope

Perseverance Rover

Parker Solar Probe

Advertisement

Understanding Sound Waves and How They Work

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

Sound. When a drum is struck, the drumhead vibrates and the vibrations are transmitted through the air in the form of sound waves . When they strike the ear, these waves produce the sensation of sound.

Technically, sound is defined as a mechanical disturbance traveling through an elastic medium — a material that tends to return to its original condition after being deformed. The medium doesn't have to be air. Metal, wood, stone, glass, water, and many other substances conduct sound — many of them even better than air.

The Basics of Sound

Sound waves, speed of sound, the behavior of a sound wave, sound quality, history of sound.

There are many sources of sound. Familiar kinds include the vibration of a person's vocal cords, vibrating strings (piano, violin), a vibrating column of air (trumpet, flute), and vibrating solids (a door when someone knocks). It's impossible to list them all because anything that imparts a disturbance to an elastic medium is a source of sound.

Sound can be described in terms of pitch — from the low rumble of distant thunder to the high-pitched buzzing of a mosquito — and loudness. Pitch and loudness , however, are subjective qualities; they depend in part on the hearer's sense of hearing. Objective, measurable qualities of sound include frequency and intensity, which are related to pitch and loudness. These terms, as well as others used in discussing sound, are best understood through an examination of sound waves and their behavior.

Speed of sound in various mediums

Air, like all matter, consists of molecules. Even a tiny region of air contains vast numbers of air molecules. The molecules are in constant motion, traveling randomly and at great speed. They constantly collide with and rebound from one another and strike and rebound from objects that are in contact with the air.

When an object vibrates it produces sound waves in the air. For example, when the head of a drum is hit with a mallet, the drumhead vibrates and produces sound waves. The vibrating drumhead produces sound waves because it moves alternately outward and inward, pushing against, then moving away from, the air next to it. The air particles that strike the drumhead while it is moving outward rebound from it with more than their normal energy and speed, having received a push from the drumhead.

These faster-moving molecules move into the surrounding air. For a moment, the region next to the drumhead has a greater-than-normal concentration of air molecules — it becomes a region of compression. As the faster-moving molecules overtake the air molecules in the surrounding air, they collide with them and pass on their extra energy. The region of compression moves outward as the energy from the vibrating drumhead is transferred to groups of molecules farther and farther away.

Air molecules that strike the drumhead while it's moving inward rebound from it with less than their normal energy and speed. For a moment, the region next to the drumhead has fewer air molecules than normal — it becomes a region of rarefaction. Molecules colliding with these slower-moving molecules also rebound with less speed than normal, and the region of rarefaction travels outward.

The nature of sound is captured through its fundamental characteristics : wavelength (the distance between wave peaks), amplitude (the height of the wave, corresponding to loudness), frequency (the number of waves passing a point per second, related to pitch), time period (the time it takes for one complete wave cycle to occur), and velocity (the speed at which the wave travels through a medium). These properties intertwine to craft the unique signature of every sound we hear.

The wave nature of sound becomes apparent when a graph is drawn to show the changes in the concentration of air molecules at some point as the alternating pulses of compression and rarefaction pass that point. The graph for a single pure tone, such as that produced by a vibrating tuning fork, would show a sine wave (illustrated here ). The curve shows the changes in concentration. It begins, arbitrarily, at some time when the concentration is normal and a compression pulse is just arriving. The distance of each point on the curve from the horizontal axis indicates how much the concentration varies from normal.

Each compression and the following rarefaction make up one cycle. (A cycle can also be measured from any point on the curve to the next corresponding point.) The frequency of a sound is measured in cycles per second or hertz (abbreviated Hz). The amplitude is the greatest amount by which the concentration of air molecules varies from the normal.

The wavelength of a sound is the distance the disturbance travels during one cycle. It's related to the sound's speed and frequency by the formula speed/frequency = wavelength. This means that high-frequency sounds have short wavelengths and low-frequency sounds have long wavelengths. The human ear can detect sounds with frequencies as low as 20 Hz and as high as 20,000 Hz. In still air at room temperature, sounds with these frequencies have wavelengths of 75 feet (23 m) and 0.68 inch (1.7 cm) respectively.