The Importance of a Learning Journey

The pursuit of knowledge has the power to transform us. A learning journey nurtures this curiosity of transformation in the learners. It offers continued learning and ensures continued growth. It uses tools that can also help learners navigate the terrain to keep learners going. One can use a it to discover what to learn, how to learn, and what they are good at. Once they understand this, they can easily use the tools and techniques provided by a learning journey to improve their knowledge.

Table of Contents

What is a learning journey, why is a learning journey important, how do you create a learning journey, how to implement it, benefits of the learning journey, infographic, knowledge check , frequently asked questions (faqs), what is the learning journey, what is an employee learning journey.

The term learning journey refers to a planned learning experience that takes place over time and includes various learning aspects and experiences using multiple techniques and platforms. Instructional designers create a learning journey to identify the appropriate format and methodology of learning. A well-structured learning journey can help the learners to achieve the objectives effectively, ensure learning implementation, and initiate actual behavioral change .

It caters to the leadership style, culture, specific needs of any organization , and the preferences of the learner’s leadership level. It also shows a more straightforward path to the learners’ learning goals, demonstrating a starting point and structured progress to help them achieve the objectives effectively. Organizations take the help of a learning journey to navigate their employees into a well-structured training process.

Organizations that employ a mixed learning journey are 2.5 times more likely to be financially successful than those that use more conventional learning approaches. (Source: DDI, Global Leadership Forecast).

Ignite Your Learning Culture: Custom eLearning Solutions

Empower your workforce with customized learning experiences that:

- Address specific learning needs – through Compliance Trainings, Process Trainings, Product & Service Training, Safety Trainings, Sales & Marketing Training, Onboarding & more!

- Boost knowledge retention – with engaging content, interactive elements & Performance Support Tools.

- Cultivate a thriving learning culture – that drives engagement, productivity & success.

Learners find the structure provided by the learning journey very helpful. It clarifies what people should do next and how much time they should set aside. It offers a high level of flexibility around where and when they should study, together with the multiple modes and channels for learning, which help embed essential skills rapidly and effectively.

The knowledge, study, and research abilities that learners bring to the learning process make up their learning journey. Since instructors are involved in designing and evaluating their education, it also offers a structural method to the learners and the instructors who are shaping the module. Instructional designers create a well-aligned learning module using a it.

In order to create a successful learning journey that is well-aligned with the organization, instructional designers try to:

- Bring attention to the prospects for learning: The goal can only be achievable when the learners understand why this learning is essential. Only then can the organizations promote a healthy learning environment .

- Describe the benefits for the employees: Adult learners are encouraged intrinsically with self-esteem, desire for a better quality of life, self-development, and recognition. Therefore, instructors must plan a well-aligned learning journey according to that.

- Use gamification , virtual and augmented reality, scenario-based learning, and branching scenarios like immersive formal learning. The effectiveness of immersive learning has been demonstrated, with assignments finished on schedule. As a result, compared to other conventional learning approaches , this style of education has a higher likelihood of producing successful results. Immersive learners always develop more extraordinary cognitive abilities than traditional learners. They exhibit better problem-solving skills, better memory, and higher attention control.

- Provide employees with access to information during work so, they know what they need when needed.

- Support formal events with performance support tools.

- Reinforce learning by providing opportunities for practice, follow-up tools, and constructive criticism.

- Offer social learning so learners can interact with those who are also learning and advancing while exchanging information and experiences. As adult learners, they are instrumental in their learning process. They are more proactive in doing the work needed to facilitate learning and drive the learning process based on what they think they have to succeed on the job . Learners bring a greater volume, quality of experience, and rich resources to one another.

See How Learning Everest Can Increase Your Training ROI

- Top-notch Quality – get the most effective courses designed by us.

- Competitive Cost – yet at the most competitive cost.

- Superfast Delivery – that too faster than your desired delivery timelines.

Instructional designers can implement it like this:

- First, they should assess the employees’ current skill levels based on the organization’s competency model. Finding and concentrating on the essential leadership skill gaps is the first step in a precise diagnosis.

- Then, learning should be applied and tested through computer-based business simulations customized to the organization’s specific needs. Simulation exercises ensure that concepts learned during the learning event apply to the organization’s real-world issues.

- Next, they can use follow-up tools to support continuing learning with additional content, case studies , and community leader boards to encourage the new learners. It utilizes several measurement techniques to quantify the effectiveness of the talent development program.

It has the following advantages:

- It helps the learners to navigate appropriately. It helps them to gain knowledge independently.

- A well-aligned learning journey brings additional structure to a learning system. It provides a structured environment that helps to maintain discipline in the learning process.

- It enables self-paced learning for the learners. It generates an individualized experience. It helps learners undertake the courses at their own pace, according to their needs. It gives the learners freedom in their choices.

- It makes it easier to define and pursue goals. It generates an achievable goal for the learners and motivates them to achieve it.

- It helps accelerate the learning and development goals of the employees as well as of the organizations.

- It saves admin time.

- It promotes a continuous feedback method that reevaluates the purpose of the journey.

- It makes learning a continuous process, a journey indeed.

- It offers to learn in small chunks. Small amounts are better for retention. It allows learners to remember and relearn the materials at their convenience.

Learning Journey

- To allow learners a competitive edge.

- To provide structured learning experience.

- To offer creativity.

- To make feedback more immediate.

- Finding and concentrating on the essential skill gaps in the organization.

- Communicating with the employees/stakeholders.

- Imposing a general training and development journey.

With the help of a learning journey, one can evaluate a learner’s progress, clarifying what they should accomplish next and how much time they should allot for it. Learners’ ability to self-evaluate their learning progress makes the learning process independent. Employee learning journeys consist of a number of distinct learning experiences that are spread out over time, utilizing various methods and delivery modalities and leading to the acquisition of new knowledge, skills, or behavioral changes at the end of the journey.

The term learning journey refers to a planned learning experience that takes place over time and includes various learning aspects and experiences using multiple techniques and platforms.

In order to create a successful learning journey that is well-aligned with the organization, instructional designers always keep the end goal in mind, recognize the gaps, extend learning over development-related activities, involve the learners to direct management, calculate the effects, and plan for flawless execution.

With the help of learning journeys, one can evaluate a learner’s progress, clarifying what they should accomplish next and how much time they should allot for it.

Employee learning journeys consist of a number of distinct learning experiences that are spread out over time, utilizing various methods and delivery modalities and leading to the acquisition of new knowledge, skills, or behavioral changes at the end of the journey.

Live Online Certification Trainings

Our Clients Our Work

How Can We Help You

- Top-notch Quality – get the most effective courses designed by us.

- Competitive Cost – yet at the most competitive cost.

- Superfast Delivery – that too faster than your desired delivery timelines.

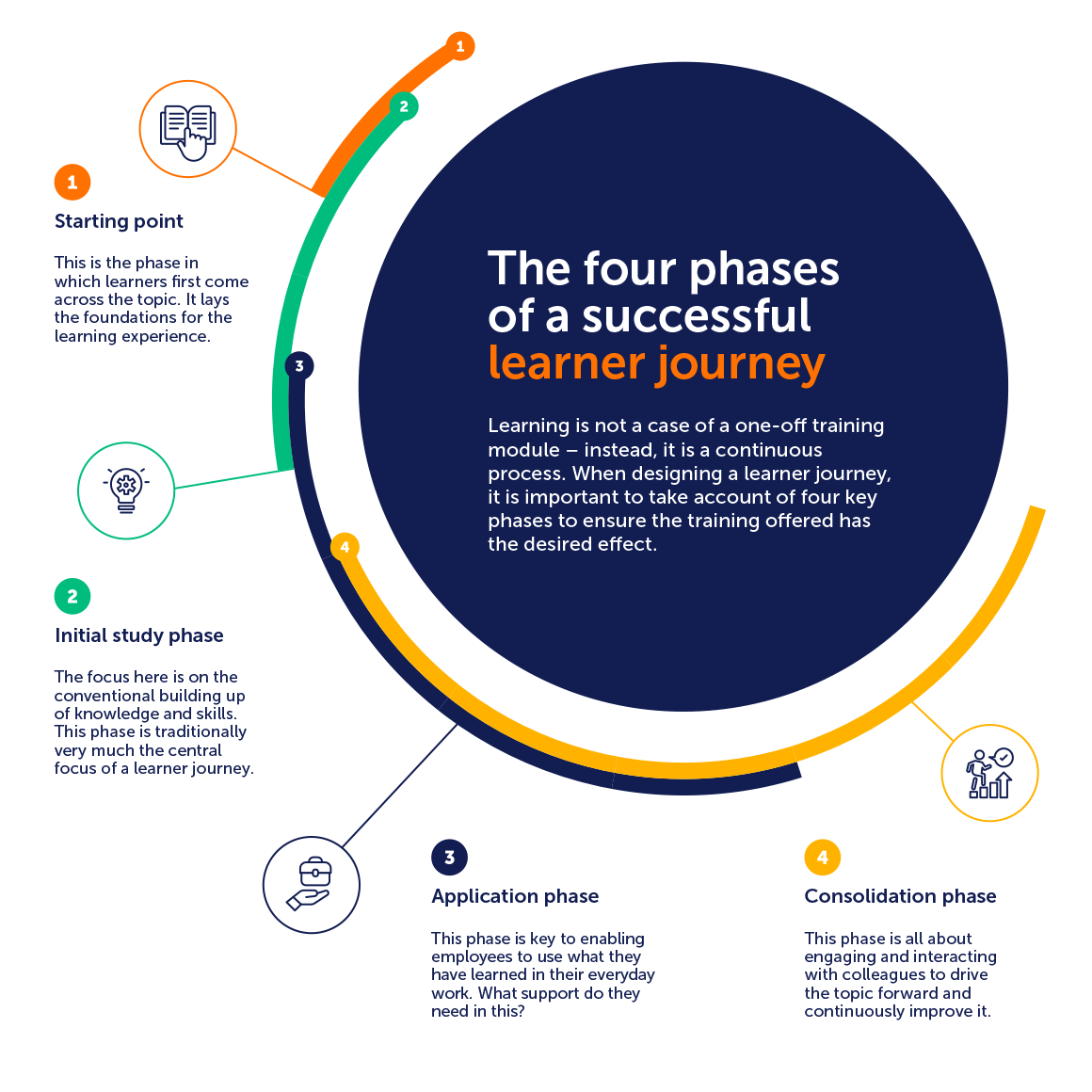

The four phases of a successful learner journey

This whole concept is very much “on trend” in the corporate world. Variants range from “independent booking”, when staff plan out their own learning route, to “Silicon Valley safaris”, when participants can take a look at the latest forms of collaboration and innovation processes at start-ups. As this range shows, there are very different views in organizations about what a journey of this kind should actually look like. This is even demonstrated by the fact that, in general, the terms “learner journey” and “learning journey” are used synonymously – just like they are in this text. After all, however vivid the journey metaphor may be, each organization will approach and organize it differently in practice.

What is a learning journey?

In an era of rapid knowledge cycles, high pressure on productivity and diversified work structures, education processes that are not integrated into the actual work and take place at a separate time are rarely successful. Occasional, isolated training sessions are not, on their own, enough to enable learners to progress and acquire knowledge and new capabilities such as the much-invoked “future skills” in an agile, direct way during their actual work. Learners therefore need to be part of both a personalized and a social process. This opens up a new perspective on not only education itself, but also on tools and formats.

There are three key features:

- The focus is not on compressing content into a single workshop, a traditional training course or a digital study module. Instead, digital options linked together in a way that makes good educational sense support employees for as long as it takes for them to internalize the new knowledge and build up the relevant skills to the point that they can apply them correctly in their everyday jobs.

- As the approach is designed from the student’s perspective, learners can choose the route and activities that meet their personal needs, progress at their own speed and reach their destination independently.

- It is not a sequence of activities in the sense of a prescribed linear route within a learning management system. Instead, it describes all activities and methods that employees use to access, assimilate and, ultimately, apply a particular topic, including adding their own experiences (e.g. expectations and concerns) into the mix, interacting with colleagues and sharing their knowledge with others.

Reflecting on experiences, learning from them and applying new knowledge in a practical setting all takes time – weeks, months or even years in some cases.

Where does a learning journey start – and where does it end?

It starts with the first contact with the topic and extends through the initial learning phase and everyday application in the working context until such time as the learner has mastered the subject and can themselves play a part in consolidating and further developing the topic or the options on offer.

The concept therefore extends far beyond the formal training. The underlying idea of the process is based on the 70:20:10 principle devised by Morgan McCall, Robert W. Eichinger and Michael Lombardo back in the 1980s. To put it in very simplified terms, according to this concept, people only acquire around 10 percent of their skills through traditional methods such as seminars, eLearning or books. The bulk of knowledge acquisition – some 90 percent or so – takes place outside the traditional context, e.g. through interaction with others.

As we observe in practice time and again, the risk of failure increases if the process comes to an end before this discussion phase has taken place. If, for example, organizations roll out a collaboration tool such as Microsoft 365 and focus exclusively on how the tool is used, key aspects will be omitted, such as the important phase of collective social learning and negotiations over how the tool should be used in the everyday working context to improve collaboration. As a result, employees receive training on specific principles, but no consideration is given to the elementary phase of collaborative work. This means countless teams are created, overwhelming staff and resulting in a sense of confusion and frustration that the project isn’t taking off.

How do I develop a successful learning journey?

Tts learner journey template.

To be successful, the journey has to encompass more than just the initial phase of knowledge acquisition – it also involves the starting point, the application in the everyday employment context and the consolidation of what has been learned through sharing, advocacy and continuous improvement. That’s because, of the four phases in total, it is only in these last two that the sustainable practical transfer of knowledge takes place – and this process is vital for subsequent value creation in the organization.

However, before we start designing the four key phases in our capacity as an HR manager or learning academy, we first need to undertake the pre-planning stage. The following points need to be clarified:

- Who are the students? A journey is always developed from the target group’s perspective (learner personas). Materials and methods are chosen to meet individual learning needs, with an increasing focus on the learning experience, i.e. personalized educational environments and experiences.

- What do students need? Before an education program can be devised, a comprehensive assessment to identify the target group’s needs and requirements is vital. This assessment takes the form of interviews and, where appropriate, an initial assessment of the realities of the work experience.

- What is the aim? Which of the organization’s strategic or performance targets need to be supported? The more clearly the educational targets and context of the target groups are defined, the more effectively a mix of formats (e.g. blended learning) and methods that mesh together and make good educational sense can be put together.

It is clear from the points outlined above that the development of learner personas is a key success factor, since very different routes will be required for different target groups.

Four key phases of the learning journey – these are what matter

It’s now a case of fleshing out the four phases in detail. In our example, we want to drive forward digital transformation and use Microsoft 365 to make it easier for sales staff at an organization to collaborate with each other.

1. Starting point

In what context do the students first come across the topic that they will be dealing with on their learner journey? Although this may be a chance encounter, such as via the office grapevine or an informal recommendation from a colleague, it is generally in the organization’s interests to specifically design the introduction to the topic, incorporating the knowledge that has been acquired by working out the personas. How is the topic relevant to students? How should students come into contact with it? To what extent do they benefit from engaging with the topic?

This phase lays the foundation for the learning experience and the subsequent learner journey experience, so particularly close attention needs to be paid to it.

2. Initial study phase

During this phase, the focus is on the “traditional” building up of knowledge and skills. It’s all about fundamental questions such as: What goals are being pursued with the change? What is the underlying idea? How do I use the tools? How do I create a team? How do we want to make use of the new options for our future collaboration? A carefully curated mix of formats is chosen for the initial stage. This may involve devising blended learning concepts that combine online sessions, workshops, virtual classrooms, study groups or learning nuggets, for example. This phase is traditionally very much the central point of focus. Participants find out what they ought to be able to do. All the essential foundations are laid for the subsequent application phase.

3. Application phase

In this phase, the focus is no longer on acquiring knowledge and skills, but instead on applying them on a daily basis and providing direct support in the workplace. If, for example, an employee needs to make use of a seldom-used feature of Microsoft 365 on a one-off basis, nobody wants to have to work through an entire course. Instead, what the user needs in these circumstances is quick, straightforward answers to their questions. The important thing is to provide the user with exactly the kind of efficient support they’re looking for in their moment of need. There are various suitable forms, such as performance support (e.g. step-by-step instructions), communities or social learning programs that help users help themselves. Organizations often neglect this phase – with the result that the tool isn’t used effectively and the expected benefits in terms of productivity and efficiency are not realized.

4. Consolidation phase

The focus in this phase is on interaction with colleagues, e.g. in a community, since this helps drive forward and improve the topic. In our specific example, experienced sales staff in a “community of practice” could work on building up knowledge management based on Microsoft 365 and transferring the insights gained through this process to the learner journey for future users. When this phase is reached, participants can themselves act as mentors, helping colleagues progress or supporting them during the onboarding process by means of user-generated content, for instance. This phase is considered the icing on the cake, since not all participants will achieve the level of expertise required for this or demonstrate the necessary commitment.

The role of HR as the “travel agent”

Even though the four phases have been set out chronologically here, this does not mean that learners actually work through them in this order. It is perfectly possible to jump between the different phases at will – the only reason for breaking the process down into the various phases is to provide guidance for structuring the learning journey. Even in phase 4, for example, it may be necessary to return to phase 2 if a new technical function becomes relevant as part of the digital transformation.

As HR managers and learning professionals, we need to ask ourselves the following fundamental question: What does our “travel agent” role in this context look like? Not all factors that contribute to the process can be planned. It is therefore important to give employees access to all the formats and options they may need – including remotely. When making the arrangements, we need to include plenty of embarkation and disembarkation points to ensure users have the option of skipping certain material. After all, focusing exclusively on the initial building up of knowledge to the extent that the whole process comes to an abrupt halt after the end of phase 2 would be a terrible waste of potential.

Related articles

Next Generation Learning: Bill Gates’s Vision

Blended learning reloaded – a classic concept is reinventing itself

Learning experience platforms (LXPs) – creating a new thirst for learning?

Informal learning – five tips for successful skills development

- Netherlands

How to Create Effective Learning Journeys that Drive Employee Performance

May 11, 2021 | By Asha Pandey

True learning and the subsequent changes in professional behavior require a learning journey that enhances professional development and leads to improved performance. In this article, I explore the connection between learning journeys and their impact on employee performance.

What Is a Learning Journey?

A learning journey is a comprehensive, continuous process of acquiring knowledge and skills, designed to facilitate long-term behavior change and professional development. Unlike traditional training, which is often a one-time event, a learning journey encompasses a series of interconnected learning experiences. These experiences combine formal training, like structured classes and webinars, with informal learning opportunities initiated either by Learning and Development (L&D) teams or individuals themselves. This approach ensures that learning is not just an isolated event but an ongoing process that integrates new knowledge and behaviors into daily work practices, leading to enhanced employee performance. Formal training serves as a foundational element within this learning ecosystem, while the incorporation of informal training elements personalizes and enriches the learning journey.

Key Characteristics of a Learning Journey:

- Structured and Ongoing: A learning journey is not a one-time event; instead, it’s a continuous process that unfolds over time, allowing individuals to evolve and adapt to new knowledge and skills. Integral to this process is the role of mentor feedback, which provides learners with essential insights and guidance, helping to refine skills and align learning objectives with real-world applications. This mentorship aspect enriches the learning journey, making it more personalized and effective.

- Customized Learning Experiences: It comprises personalized content and a variety of delivery methods tailored to meet the unique needs and goals of individuals or teams.

- Formal and Informal Components: It combines formal training programs with informal learning opportunities , creating a holistic approach that caters to different learning preferences.

- Behavioral Focus: The primary goal is to induce positive behavioral changes, leading to improved employee performance and alignment with organizational objectives.

What is the Difference Between Traditional Training and Learning Journeys?

The key differences between traditional training and learning journeys can be summarized as follows:

Format and Structure:

- Traditional Training: Often one-time, event-based sessions.

- Learning Journeys: Continuous, multi-step processes.

Learning Approach:

- Traditional Training: Typically focuses on immediate skill acquisition.

- Learning Journeys: Emphasizes long-term development and application.

Customization:

- Traditional Training: Generally one-size-fits-all.

- Learning Journeys: Tailored to individual learning styles and needs.

Engagement and Interaction:

- Traditional Training: Can be more passive in nature.

- Learning Journeys: Encourages active participation and engagement.

Outcome and Impact :

- Traditional Training: Aimed at knowledge transfer.

- Learning Journeys: Focuses on behavioral change and performance improvement.

Why Should You Invest in Learning Journeys?

In North America’s animal kingdom, the coyote has demonstrated exceptional learning abilities, thriving in various environments. When Meriwether Lewis in the early 19th century first encountered a coyote on his famous exploration, he was perhaps the first of European descent to see one. He attempted to kill and collect it as a new specimen. He and his men were unsuccessful though – an experience that thousands of American hunters have shared since. The coyote has learned to adapt and thrive to constant changes in their ecosystem and are now a common sighting in large cities like San Francisco (California) and Salt Lake City (Utah).

In business, those who can learn are the coyotes – they can adapt and thrive to changing circumstances. Companies should find and develop coyotes in their organizations – employees who actively participate in their own learning journeys and contribute to the journey of their coworkers.

Benefits of Learning Journeys from a Business Perspective:

- Customization for Strategic Alignment: Learning journeys offer highly customized programs designed to align with an organization’s key goals and objectives. They are structured to address specific enterprise challenges and opportunities, ensuring that the learning journey directly supports the business’s strategic direction.

- Future-Proofing the Business: By structuring learning journeys around key enterprise goals, organizations are better prepared to face future challenges. This proactive approach drives both incremental and disruptive innovation, allowing businesses to adapt and thrive in a rapidly changing landscape.

- Improved Employee Engagement: Organizations that value learning and encourage professional development through learning journeys experience heightened employee engagement. Employees are more motivated and committed when they feel their growth is supported and recognized.

Benefits of Learning Journeys from an Employee’s Perspective:

- Guidance for Skill Enhancement: Learning journeys serve as a GPS for individual learners, guiding them through the process of skill acquisition and proficiency development. They offer a clear path through formal and informal learning, helping employees enhance their skills and expertise.

- Motivation and Awareness: Learning journeys provide motivation and awareness, inspiring individuals to take charge of their own development. They create a sense of purpose and direction, encouraging learners to proactively seek knowledge and growth opportunities.

- Learning Consumption and Application: These structured journeys guide learners through the stages of learning consumption and knowledge application, ensuring that the acquired skills and knowledge are put into practice effectively.

- Relevance to Career Aspirations: Learning journeys are highly relevant to individuals, assisting them in achieving their career aspirations. Whether it’s mastering a specific role or acquiring expertise in a particular technological domain, these journeys support individual growth and development.

Learning journeys offer a dual advantage, benefiting both the organization and its employees. They align learning and development with business goals, promoting innovation and engagement. From the employee’s perspective, learning journeys provide a clear path for skill enhancement, motivation, and relevance to career aspirations, ultimately driving continuous improvement and professional development.

Drawbacks of Learning Journeys

While learning journeys offer a comprehensive approach to professional development, they are not without their challenges. Here are some potential drawbacks:

Resource Intensive:

- Designing a learning journey requires significant time and resources. This includes the creation of tailored content, monitoring progress, and providing ongoing support and feedback.

Can Overwhelm Learners:

- The extensive nature of learning journeys may overwhelm some individuals, particularly if the content is dense or the pace is too fast.

Requires High Commitment:

- To be effective, learning journeys demand a high level of commitment and self-motivation from learners, which can be challenging to maintain over longer periods.

Potential for Inconsistency:

- In a diverse learning environment, ensuring a consistent experience for all learners can be difficult, especially if the journey involves various instructors or methods.

Dependence on Technology:

- Learning journeys often rely on digital platforms and tools, which can be a barrier for learners with limited access to technology or those who are less tech-savvy.

Evaluation Challenges:

- Measuring the effectiveness of a learning journey can be complex, as it involves evaluating progress over an extended period and across various learning formats.

Why Do Learning Journeys Work

Learning journeys function as a structured approach to professional and personal development. Here’s how they typically work:

- Initial Assessment : Identifying individual learner needs and goals.

- Customized Learning Path : Designing a personalized learning plan based on the initial assessment.

- Diverse Learning Methods : Incorporating various formats like online modules, workshops, and real-world assignments.

- Ongoing Support : Providing mentorship, peer interaction, and resources throughout the journey.

- Continuous Feedback : Regular assessments and feedback to track progress and adjust the learning path.

- Real-world Application : Opportunities for applying learned skills in practical settings.

- Reflection and Adaptation : Encouraging learners to reflect on their progress and adapt their learning strategies.

This process ensures that learning is an ongoing, evolving journey tailored to each individual’s needs and goals, leading to effective skill development and personal growth.

How to Create an Effective Learning Journey?

The following are vital issues to consider when building learning journeys:

- Consider the overarching vision, acknowledging that the future, though uncertain, is always present. Learning occurs over prolonged time and should never been something that employees stop doing, nor should organizations ever rest on their previous laurels. Integrating spaced learning and repetition into this process is crucial, as it greatly contributes to better knowledge retention, allowing learners to revisit and reinforce concepts at regular intervals, thereby solidifying their understanding and application in practical scenarios.

- Awareness: Before employees can begin a learning journey, they need to be aware of what is available, how the organization will support them, and what lies ahead.

- Motivation: While some employees are motivated for the pure sake of learning, some are looking for additional extrinsic motivations. Organizations should set up systems to reward progression in the learning process, encouraging employees to begin and continue the learning journey.

- Participation and experimentation: Throughout the learning journey, employees need a safe space to participate, digest, apply, and experiment with the new knowledge they’re gaining through the learning journey. The experimentation and feedback loop are key to achieving behavior change.

- On-going connects: Design learning journeys that include more than formal training events. Develop guides for managers to follow-up with employees on what they learned, implement social and mobile learning strategies, and allow employees to direct much of their own informal learning.

What are the Key Components of a Learning Journey?

A well-structured learning journey comprises several key components that work in tandem to ensure effective and engaging education experiences. These components are critical in shaping a comprehensive learning path that caters to diverse learning styles and objectives.

Needs Analysis and Goal Setting:

- Identifying specific learning needs and objectives.

- Setting clear, measurable goals for the learning journey.

Varied Learning Formats:

- Incorporation of diverse learning methods such as online courses, workshops, and practical exercises.

- Blending formal with informal learning opportunities.

Personalization and Flexibility:

- Tailoring content to meet individual learner’s needs and preferences.

- Offering flexible learning paths that accommodate different learning paces.

Continuous Assessment and Feedback:

- Regular evaluations to track progress.

- Providing timely feedback to guide and improve learning.

Application and Reinforcement:

- Opportunities to apply learned skills in real-world scenarios.

- Reinforcement activities to ensure retention and integration of new knowledge.

Support and Resources:

- Access to necessary learning materials and resources.

- Support from instructors, mentors, or peer groups.

These components collectively ensure that a learning journey is not only comprehensive but also adaptable, engaging, and result-oriented.

What Are Key Aspects that Would Help You Create Effective Learning Journeys?

Leverage the following aspects when developing learning journeys:

- Start with the end in mind : Planning is too often abbreviated in the L&D field, a reaction to develop content as quickly as possible to please business stakeholders. Remember what Albert Einstein said about planning: “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.”

- Include all stakeholders: During the initiation phase, include key stakeholders and ensure that everyone involved in the process has the information they need. Leaders should ask themselves the following questions: What do I know? Who needs to know? Have I told them?

- Build awareness of the solution with the target audience : Begin with primers to help them understand the big picture of the learning journey. Include an exposition on the current state, the desired future state, and the differences between those two states. Use microlearning hits that get to the point quickly.

- Stimulate prior knowledge with which learners can scaffold new information.

- Present content in the most appropriate modality.

- Model learning strategies to help students assimilate new information.

- Include as much application and practice as possible with healthy feedback loops.

- Assess performance, giving additional feedback to learners.

- Once learners are back on the job, use informal learning and coaching nudges to reinforce the application of new knowledge on the job. Employ performance support systems so learners can quickly find and share information they need in the flow of work.

- Reward behavior change : While punitive rewards may be effective in the short term, for effective long-term behavior change, learning journeys should offer employees as much purpose, autonomy, and mastery as possible. Once employees are paid a fair and competitive wage, purpose, autonomy, and mastery are more effective methods of motivation than even bonus models.

Making It Work – EI’s Learning and Performance Ecosystem Based Approach to Create Effective Learning Journeys

EI has developed a highly effective model for creating effective learning journeys in a Learning and Performance Ecosystem . It’s a cyclical model that includes the following:

- Capture attention about learning opportunities.

- Explain what employees will gain from the learning journey (what’s in it for me).

- Leverage immersive formal learning events that employ gamification, virtual and augmented reality, scenario based learning, and branching scenarios.

- Support formal events with performance support tools, giving employees access to information in the flow of work : exactly what they need, when they need it.

- Reinforce learning after formal events with safe places to practice and receive feedback on their performance.

- Provide social learning so that learners can collaborate with others progressing in the learning journey, sharing knowledge and experiences.

Learning Journey Example: Sales Training

In our sales training program, we use the Learning and Performance Ecosystem framework to structure an effective learning journey for our team. Here’s how it aligns with the framework:

● Capture Attention : We kick off the learning journey by capturing the attention of our sales team about the upcoming training. This may include email announcements, intranet notifications, and engaging teasers to generate excitement.

● Explain the Benefits : We clearly communicate what participants will gain from the training journey. This includes improved sales skills, increased sales performance, and the potential for enhanced career growth.

● Immersive Formal Learning Events : We leverage immersive formal learning events that employ various cutting-edge techniques, such as gamification, virtual and augmented reality, scenario-based learning, and branching scenarios. These events make the learning experience engaging and memorable.

● Performance Support Tools : We provide performance support tools to our sales team, offering quick access to information in the flow of work. They can access product details, sales scripts, and negotiation tips exactly when needed.

● Reinforcement and Practice : After formal training events, we create safe spaces for our sales team to practice and receive feedback on their performance. This may involve role-playing exercises, simulated sales calls, and peer evaluations.

● Social Learning : We encourage social learning, allowing learners to collaborate with colleagues who are progressing in the training journey. They can share knowledge, experiences, and best practices, fostering a sense of community and continuous improvement.

This sales training learning journey not only equips our sales team with the necessary skills and knowledge but also keeps them engaged and motivated throughout the process. By aligning with the Learning and Performance Ecosystem framework, we ensure a comprehensive and effective approach to sales training that yields tangible results and benefits for both our team and the organization.

Parting Thoughts

Effective behavior change occurs over time as desired competencies and behaviors are reinforced through a blend of formal and informal training. Learning is not a one-time event. Professionals seek mastery of their trade, striving for autonomy and purpose. Learning journeys, thoughtfully developed and shared with employees, are an effective method of facilitating behavior change that aligns to enterprise goals and initiatives.

I hope this article provides the requisite insights on how you can use our unique Learning and Performance Ecosystem to create effective learning journeys and boost employee performance.

- Recent Posts

- Enhance Your Learning Strategy with the eLearning Trends in 2019 - August 8, 2020

Write to us!

If you want to book a demo or if you want to consult an expert write to us. We will get back

Related Insights

Articles

The Time for an L&D Audit Is Now

The word audit typically evokes negative connotations. A tax audit or a compliance audit is rarely anticipated with delight. However,…

> Read Insight

Tips And Examples To Create Highly Engaging Online Compliance Training

While online compliance training is commonly perceived as dull, it possesses the potential for engaging and captivating learning experiences. This…

Top 10 Microlearning Trends to Adopt in 2024

What is Microlearning? Microlearning is a learning approach that leverages short, bite-sized training nuggets to improve knowledge gain. Typically designed…

How to Create an mLearning Strategy for Your Corporate Training Programs

With a large percentage of the workforce working remotely, mLearning is a must-have strategy for the new learning environment. In…

Request a demo

First Name *

Last name *

I am interested in...

Write to our HR team

Send job application.

Attach Resume *

Your message

First Name * Last Name * Email * Company Job Title

Company Job Title

You can see how this popup was set up in our step-by-step guide: https://wppopupmaker.com/guides/auto-opening-announcement-popups/

Create a Learning Journey for Leaders

LEARNING JOURNEY

What Is a Learning Journey?

A learning journey is a strategic approach to developing groups of leaders over time. It’s based on the principle that true behavior change takes time, and that people learn best together—as long as they can personalize their experience.

At DDI, we create learning journeys to maximize the time and effectiveness of leadership development . Learning journeys offer the right blend of personalized learning with group connection. For example, leaders can take assessments, pursue online learning, and coaching to boost their knowledge and insight. But they cement learning when they come together in virtual or in-person classroom sessions.

Ready to get started? We offer proven, competency-based learning journeys you can implement right away. Or we can work with you to create a completely custom learning journey, just for you. Either way, we’re ready to start walking by your side as your leaders begin their transformation.

Compared to Companies That Use More Traditional Learning Methods, Companies That Use a Blended Learning Journey Are:

more likely to be financially successful

more likely to have a highly-rated development program

more likely to have a strong leadership bench

Learn how Commvault built a global leadership development program with content from DDI's leadership development subscription.

How Commvault Develops Leaders Strategically with a DDI Leadership Development Subscription

A one-and-done or an eight-hour-long Zoom session wasn’t going to cut it. That’s why we moved to the concept of a learning journey that included content delivered in shorter sprints, but delivered over a period of time

— Joe Ilvento, Chief Learning Officer at Commvault

Explore Sample Learning Journeys

A learning journey to help leaders build morale and engagement to retain talent.

Boost Team Engagement

Take your leaders on a learning journey to create a coaching culture that boosts performance.

Build a Coaching Culture

This learning journey will help leaders practice inclusion to create a welcoming, supportive environment for all.

Develop Inclusive Leadership

Design Your Own Learning Journey

With a DDI Leadership Development Subscription, you get a dedicated strategic learning team who will work with you to create a custom program, just for your leaders.

We start by understanding the business goals you need to accomplish. From there, we’ll work by your side to curate the perfect blend of content to ensure your leaders will gain the right skills. Then we’ll tailor learning formats that will best fit your culture and your leaders’ needs.

Explore subscriptions

Want to Take Things Virtual?

At DDI, we’re big believers in the power of learning together. But that doesn't mean it has to be in-person.

As many companies have shifted to a virtual workplace, we’ve taken leadership development with it. We offer learning journeys that take place entirely in the virtual world.

But that doesn’t mean you miss out on human connection. Our virtual classroom format creates the same bond leaders get in the classroom – just without handshakes.

Learn about virtual classroom

Don’t Forget Microlearning

The key to creating successful learning journeys is to sustain learning in between classroom sessions. And that’s where microlearning comes in.

Microlearning offers quick learning experiences that help leaders practice and deepen their skills between larger learning sessions. It can be things like short courses, videos, self-assessments, online tools, or other quick formats.

In just a few minutes, microlearning offers a quick boost to keep your leaders engaged.

Explore microlearning

recommended Resources

How one company developed a frontline leadership learning journey with elements of both digital learning content and in-person classroom experiences.

How We Did It: Creating a Frontline Leadership Learning Journey

Explore best practices for how to create a learning journey and learn why this approach is crucial for a company’s leadership development strategy.

How to Design an Effective Learning Journey

DDI’s Ultimate Guide to Leadership Development gives HR pros everything they need to create and launch powerful leadership development experiences.

Ultimate Guide to Leadership Development

The online magazine for those involved in workplace learning, performance and development

Creating a great learning journey

Diane Law provides a tool to deliver the right learning to the right people at the right time.

Driving change through learning

What is responsible leadership?

How to motivate teams and cultivate talent

Transforming learning with virtual reality

- Identifying the key lessons and outcomes at a detailed level

- Determining what blend of each EPIC component would best serve which aspects of the programme. An example of some questions you can ask at this stage are:

- How important is it to practice this skill in a real-world environment? Are there opportunities for stretch assignments or special projects to enhance the skill/behaviour? (E)

- Do people need to work together to come up with solutions? How important is immediate feedback? Are there subject matter experts who can offer some guidance? (P)

- Does the content need to be accessed at the point of need? Would providing videos, tip sheets, etc. be useful or not likely accessed? (I)

- Does working in a group enhance the learning? Is practice in a ‘safe’ environment important? (C)

- Planning at a high level the order in which each intervention should occur

- Ensuring that there is a good balance of each approach – and not defaulting to classroom type learning!

Related Posts

Future human: cultivating resilience for the 21st century

Why fraud prevention training should be on your L&D agenda

Book excerpt: make brilliant work, mary.isokariari, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Search entire site

- Search for a course

- Browse study areas

Analytics and Data Science

- Data Science and Innovation

- Postgraduate Research Courses

- Business Research Programs

- Undergraduate Business Programs

- Entrepreneurship

- MBA Programs

- Postgraduate Business Programs

Communication

- Animation Production

- Business Consulting and Technology Implementation

- Digital and Social Media

- Media Arts and Production

- Media Business

- Media Practice and Industry

- Music and Sound Design

- Social and Political Sciences

- Strategic Communication

- Writing and Publishing

- Postgraduate Communication Research Degrees

Design, Architecture and Building

- Architecture

- Built Environment

- DAB Research

- Public Policy and Governance

- Secondary Education

- Education (Learning and Leadership)

- Learning Design

- Postgraduate Education Research Degrees

- Primary Education

Engineering

- Civil and Environmental

- Computer Systems and Software

- Engineering Management

- Mechanical and Mechatronic

- Systems and Operations

- Telecommunications

- Postgraduate Engineering courses

- Undergraduate Engineering courses

- Sport and Exercise

- Palliative Care

- Public Health

- Nursing (Undergraduate)

- Nursing (Postgraduate)

- Health (Postgraduate)

- Research and Honours

- Health Services Management

- Child and Family Health

- Women's and Children's Health

Health (GEM)

- Coursework Degrees

- Clinical Psychology

- Genetic Counselling

- Good Manufacturing Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Speech Pathology

- Research Degrees

Information Technology

- Business Analysis and Information Systems

- Computer Science, Data Analytics/Mining

- Games, Graphics and Multimedia

- IT Management and Leadership

- Networking and Security

- Software Development and Programming

- Systems Design and Analysis

- Web and Cloud Computing

- Postgraduate IT courses

- Postgraduate IT online courses

- Undergraduate Information Technology courses

- International Studies

- Criminology

- International Relations

- Postgraduate International Studies Research Degrees

- Sustainability and Environment

- Practical Legal Training

- Commercial and Business Law

- Juris Doctor

- Legal Studies

- Master of Laws

- Intellectual Property

- Migration Law and Practice

- Overseas Qualified Lawyers

- Postgraduate Law Programs

- Postgraduate Law Research

- Undergraduate Law Programs

- Life Sciences

- Mathematical and Physical Sciences

- Postgraduate Science Programs

- Science Research Programs

- Undergraduate Science Programs

Transdisciplinary Innovation

- Creative Intelligence and Innovation

- Diploma in Innovation

- Transdisciplinary Learning

- Postgraduate Research Degree

Learning Journeys

The world is complex and uncertain. To survive and thrive you need to develop your ability to adapt the way you learn (your Learning Power). You can use Learning Journeys to discover how you learn and, what you are good at. Once you understand this, you can use the tools and techniques provided by Learning Journeys to improve your Learning Power.

Welcome to the UTS Learning Journeys website!

This exciting resource has been created to help students and staff at all levels to reflect on our readiness for new challenges.

Why the big focus on preparing for change? Because that’s basically the only thing we can be sure the future holds — we will run increasingly into situations that require us to step out of our comfort zones.

As a student these might be in your university studies, jobs, internships or co-curricular activities, while Staff will be reflecting on the challenges of their professional roles.

You have a lifetime of learning-on-the-job ahead of you, most likely mixed with formal training or education, as you pivot and prep yourself for new roles and projects.

We need new ways of thinking, and new ways of working with others. All the evidence is that this requires new levels of self-awareness and personal reflection, and this is what the Learning Journeys tool is designed to help with.

It asks you to honestly assess how you handle challenging learning, and gives you instant feedback to reflect on, called your Learning Power profile. This isn’t a grade, and you don’t have to show this to anyone else if you don’t want to. It’s a mirror to reflect on, to see if it helps you see yourself in a new way.

The Learning Power profile introduces a language for learning and over a decade’s educational research shows that many people at all ages and stages of life have found this helpful.

So, this website explains what a Learning Journey offers you, and shares stories of how students and staff are already using it here at UTS.

Our experience shows that it’s important that you take a bit of time to understand how to get the most out of it before diving in.

Once you’re ready, then you can click through to the tool, sign in, and embark on your Learning Journey!

What is Learning Power?

How do Learning Journeys work?

What are Learning Dimensions?

For students

For academics

For professionals

Understanding your Learning Power profile

UTS acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, the Boorooberongal people of the Dharug Nation, the Bidiagal people and the Gamaygal people, upon whose ancestral lands our university stands. We would also like to pay respect to the Elders both past and present, acknowledging them as the traditional custodians of knowledge for these lands.

Title Block

- Strategy Execution & Business Transformation

- Leader Readiness & Development

- Go to Market

- Talent Acquisition & Succession

- Strategy Execution

- Business Acumen

- Leadership Development

- Change & Transformation

- Sales & Marketing

- Leadership Coaching

- Executive & Team Performance

- Digital Services

- Diversity Equity Inclusion

- Leadership Team

- Sustainability

- Social impact

- Client stories

- In the news

- Newsletters

The Power of Learning Journeys for Leadership Development

Published on: February 2017

Written by: Rommin Adl

Copied to clipboard

I recently read an HBR article discussing why the traditional approach to leadership development doesn’t always work.

It stated that instead of traditional methods, the best way to identify, grow and retain leaders to meet today’s demands is to “Let them innovate, let them improvise and let them actually lead.”

Over the past 30 years, as we’ve partnered with clients facing a vast range of challenges, we’ve seen the truth behind this – that people learn best by actually doing. That’s why business simulations are such a powerful tool: they allow people to do and lead within a risk-free environment, and condense years of on-the-job learning experience into a few days, or even hours.

We also know that learning is not just a “one and done” situation – it is a continuous experience. In many cases, a learning journey, which blends a variety of learning methodologies and tools over time, is the most powerful means of shifting mindsets, building capabilities and driving sustained, effective results.What a learning journey looks like depends entirely on the context of your organization. What challenges are you addressing? What results are you driving for? What does great leadership look like for your organization?

To bring this to life, imagine the following approach to a blended learning journey for aligning and developing leaders – in this scenario, within a financial services firm: Financial technology has “transformed the way money is managed. It affects almost every financial activity, from banking to payments to wealth management. Startups are re-imagining financial services processes, while incumbent financial services firms are following suit with new products of their own.”

For a leading financial services company, this disruption has led to a massive technology transformation. With tens of thousands of employees in the current technology and operations group, the company will be making massive reductions to headcount over the next five years as a result of automation, robotics and other technology advances.

This personnel reduction and increased use of technology is both a massive shift for the business as well as a huge change in the scope of responsibility that the remaining leaders are being asked to take on moving forward. As such, the CEO of the business unit recognizes the need to align 175 senior leaders in the unit to the strategy and the future direction of the business, and give them the capabilities that they need to effectively execute moving forward.

To achieve these goals, BTS would build an innovative design for this initiative: a six-month blended experience, incorporating in-person events, individual and cohort-based coaching sessions, virtual assessments and more. Throughout the journey, data would be captured and analyzed to provide top leadership with information about the participants’ progress – and skill gaps – on both an individual and cohort level, thus setting up future development initiatives for optimal success.

The journey would begin with a two-day live conference event for the 175 person target audience, incorporating leader-led presentations about the strategy. The event would not just be talking heads and PowerPoint slides, but rather would leverage the BTS Pulse digital event technology to increase engagement and create a two-way, interactive dialogue that captures the participants’ ideas and suggestions. Participants also would use the technology to experience a moments-based leadership simulation that develops critical communications, innovation and change leadership capabilities, among other skills.

After the event, participants would return to the job to apply their new learnings. On the job, each participant would continue their journey with four one-on-one performance coaching sessions , in addition to a series of peer coaching sessions shared with four to five colleagues. They also would use 60-90 minute virtual Practice with an Expert sessions to develop specific skill areas in short learning bursts, and then practice those skills with a live virtual coach. Throughout the journey, participants would access online, self-paced modules that contain “go-do activities” to reinforce and encourage application of the innovation leadership and other skills learned during the program.

As a capstone, six months after the journey has begun, every participant would go through a live, virtual assessment conducted via the BTS Pulse platform. In three to four hours, these virtual assessments allow live assessors to evaluate each leader’s learnings from the overall journey and identify any remaining skill gaps. The individual and cohort assessment data would then lead to and govern the design of future learning interventions that would continue to ensure the leaders are capable of implementing the strategy.

As you can see, this journey design leverages a range of tools and learning methodologies to create a holistic, impactful solution. It’s not just a standalone event – each step of the journey ties into the one before, and the data gathered throughout can be used well into the future in order to shape the next initiative .

Great journeys or experiences like this can take many forms. In addition to live classroom and virtual experiences, there is an ecosystem of activities, such as performance coaching, peer coaching, practice with an expert, go-dos, self-paced learning modules, and more, that truly engage leaders and ensure that the learnings are being reinforced, built upon, practiced and implemented back on the job. We find that these types of experience rarely look the same for every client. There are many factors that determine which configuration and progression will make the most sense. There is one common theme that we have found throughout these highly contextual experiences, however – that the participant feedback is outstanding and the business impact is profound.

“We have one more shot” 7 reasons why CRM implementations fail and how to make yours a success

March 29, 2024

Develop a staying, growing, thriving culture

February 13, 2024

Harnessing the Power of Business Simulations: Why they are key to organizational effectiveness

January 31, 2024

How risk leadership leads to better, more rational decisions

January 25, 2024

Ready to start a conversation?

Want to know how BTS can help your business? Fill out the form below, and someone from our team will follow up with you.

- Virtual Reality

- Video-Based Learning

- Screen Capture

- Interactive eLearning

- eLearning Resources

- Events and Announcements

- Adobe Learning Manager

- Adobe Connect

- Recent Blogs

- VR projects

- From your computer

- Personalize background

- Edit video demo

- Interactive videos

- Software simulation

- Device demo

- System audio / narration

- High DPI / Retina capture

- Responsive simulation

- Full motion recording

- Advanced actions

- Conditional actions

- Standard actions

- Execute Javascript

- Shared actions

- Learning interactions

- Drag and Drop interactions

- eLearning Community

- Tutorials/Training

- Deprecated features

- Support questions

- New version

- Reviews/Testimonials

- Sample projects

- Adobe eLearning Conference

- Adobe Learning Summit

- Customer meetings

- Announcements

- Adobe Captivate Specialist Roadshows

- Account settings

- Active fields

- Activity modules

- Adobe Captivate Prime

- Auto enrollment using learning plans

- Automating user import

- LMS Branding

- Certifications

- Classroom trainings

- Content curation

- Content storage

- Course level reports

- Create custom user groups

- Customize email templates

- Default fields

- eLearning ROI

- Employee as learners

- Extended eLearning

- External learners

- Fluidic player

- Gamification and badges

- getAbstract

- Harvard ManageMentor

- Integration with Adobe Connect and other video conferencing tools

- Integration with Salesforce and Workday

- Integration with third-party content

- Integrations

- Internal and external users

- Internal server

- Learner dashboard

- Learner transcripts

- Learning objects

- Learning plan

- Learning programs

- Learning styles

- LinkedIn Learning

- LMS implementation

- Managing user groups

- Multi tenancy

- Multi-scorm-packager

- Overview of auto-generated user groups

- Prime integration

- Self-Paced trainings

- Set up announcements

- Set up external users

- Set up gamification

- Set up internal users

- Single sign-on

- Social learning

- Tincan/xAPI

- Types of course modules

- Virtual classroom trainings

- Accessibility

- Adobe Connect Mobile

- Breakout Rooms

- Case Studies

- Collaboration

- Connectusers.com

- Customer Stories

- Product updates

- Social Learning

- Virtual Classrooms

- Virtual Conferences

- Virtual Meetings

- Unified Communications

- Free Projects

- Learning Hub

- Discussions

- eLearning Community Follow

True learning and implied behavior change requires a learning journey to boost professional development and achieve improved performance. In this article, we look at the link between learning journeys and how it can improve employee performance.

True learning and implied behavior change requires a learning journey to boost professional development and achieve improved performance. In this article, I look at the link between learning journeys and how it can improve employee performance.

What Is a Learning Journey?

Traditional training has often been viewed as a one-time event: a training class, a webinar, a learning module.

However, if the goal of training is a change in behavior, which leads to improved employee performance, training should, instead, be viewed as a learning journey – a series of learning events made up of a blend of formal and informal interventions, nudges, and follow-ups that ingrain new knowledge and behavior in employees.

- Formal training is one of the key elements of a learning ecosystem that typically facilitates the learning acquisition.

- As you add informal training (some initiated by L&D teams, some initiated by individuals and coached by leaders), you create a learning journey.

Why Should You Invest in Learning Journeys?

Learning is the key to thriving business.

In the animal kingdom of North America, the coyote has perhaps proven to be the most apt at learning and has therefore thrived. When Meriwether Lewis in the early 19 th century first encountered a coyote on his famous exploration, he was perhaps the first of European descent to see one. He attempted to kill and collect it as a new specimen. He and his men were unsuccessful though – an experience that thousands of American hunters have shared since. The coyote has learned to adapt and thrive to constant changes in their ecosystem and are now a common sighting in large cities like San Francisco (California) and Salt Lake City (Utah).

In business, those who can learn are the coyotes – they can adapt and thrive to changing circumstances. Companies should find and develop coyotes in their organizations – employees who actively participate in their own learning journeys and contribute to the journey of their coworkers.

From a business perspective , learning journeys provide highly customized programs that are structured around key enterprise goals and objectives. Leaders should provide this insight to help prepare their organization for future challenges.

Not only does this help futureproof their business by driving incremental and disruptive innovation but it also improves employee engagement. Employees are looking for organizations that value learning and encourage professional development.

Organizations benefit from employees who continuously strive for improvement.

From the employee’s perspective , the learning journey acts as a GPS that guides learners in their efforts, through formal and informal learning, to perfect their art by acquiring new skills and proficiencies in business domains and technological mastery. These GPSs guide learners through motivation, awareness, learning consumption, and knowledge application.

Learning journeys comprise formal and informal learning – opportunities to acquire skills for a specific role or technological domain. They are highly relevant to the individual, assisting him/her with his/her career aspirations.

What Do You Need to Consider While Creating an Effective Learning Journey?

The following are vital issues to consider when building learning journeys:

- Look at the big picture and consider that, while foggy, the future is ever present. Learning occurs over prolonged time and should never been something that employees stop doing, nor should organizations ever rest on their previous laurels.

- Awareness : Before employees can begin a learning journey, they need to be aware of what is available, how the organization will support them, and what lies ahead.

- Motivation : While some employees are motivated for the pure sake of learning, some are looking for additional extrinsic motivations. Organizations should set up systems to reward progression in the learning process, encouraging employees to begin and continue the learning journey.

- Participation and experimentation : Throughout the learning journey, employees need a safe space to participate, digest, apply, and experiment with the new knowledge they’re gaining through the learning journey. The experimentation and feedback loop are key to achieving behavior change.

- On-going connects: Design learning journeys that include more than formal training events. Develop guides for managers to follow-up with employees on what they learned, implement social and mobile learning strategies, and allow employees to direct much of their own informal learning.

What Are Key Aspects that Would Help You Create Effective Learning Journeys?

Leverage the following aspects when developing learning journeys:

- Start with the end in mind : Planning is too often abbreviated in the L&D field, a reaction to develop content as quickly as possible to please business stakeholders. Remember what Albert Einstein said about planning: “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.”

- Include all stakeholders: During the initiation phase, include key stakeholders and ensure that everyone involved in the process has the information they need. Leaders should ask themselves the following questions: What do I know? Who needs to know? Have I told them?

- Build awareness of the solution with the target audience : Begin with primers to help them understand the big picture of the learning journey. Include an exposition on the current state, the desired future state, and the differences between those two states. Use microlearning hits that get to the point quickly.

- Stimulate prior knowledge with which learners can scaffold new information.

- Present content in the most appropriate modality.

- Model learning strategies to help students assimilate new information.

- Include as much application and practice as possible with healthy feedback loops.

- Assess performance, giving additional feedback to learners.

- Once learners are back on the job, use informal learning and coaching nudges to reinforce the application of new knowledge on the job. Employ performance support systems so learners can quickly find and share information they need in the flow of work.

- Reward behavior change : While punitive rewards may be effective in the short term, for effective long-term behavior change, learning journeys should offer employees as much purpose, autonomy, and mastery as possible. Once employees are paid a fair and competitive wage, purpose, autonomy, and mastery are more effective methods of motivation than even bonus models.

Making It Work – EI Design’s Learning and Performance Ecosystem Based Approach to Create Effective Learning Journeys

EI Design has developed a highly effective model for creating effective learning journeys in a Learning and Performance Ecosystem. It’s a cyclical model that includes the following:

- Capture attention about learning opportunities.

- Explain what employees will gain from the learning journey ( what’s in it for me ).

- Leverage immersive formal learning events that employ gamification, virtual and augmented reality, scenario based learning, and branching scenarios.

- Support formal events with performance support tools , giving employees access to information in the flow of work: exactly what they need, when they need it.

- Reinforce learning after formal events with safe places to practice and receive feedback on their performance.

- Provide social learning so that learners can collaborate with others progressing in the learning journey, sharing knowledge and experiences.

Parting Thoughts

Effective behavior change occurs over time as desired competencies and behaviors are reinforced through a blend of formal and informal training. Learning is not a onetime event. Professionals seek mastery of their trade, striving for autonomy and purpose. Learning journeys, thoughtfully developed and shared with employees, are an effective method of facilitating behavior change that aligns to enterprise goals and initiatives.

I hope this article provides the requisite insights on how you can use our unique Learning and Performance Ecosystem to create effective learning journeys and boost employee performance.

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Advertisement

Learning journey: Conceptualising “change over time” as a dimension of workplace learning

- Original Paper

- Published: 07 May 2022

- Volume 68 , pages 81–100, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Adeline Yuen Sze GOH ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4263-5712 1

5016 Accesses

5 Citations

15 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Understanding how individuals learn at work throughout their lives is significant for discussions of lifelong learning in the current era where changes can be unpredictable and frequent, as illustrated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite a corpus of literature on the subject of “learning”, there is little research or theoretical understanding of “change over time” as a dimension of individual learning at work. Increasing emphasis has been put on individuals’ personal development, since they play key mediating roles in organisations’ work practices. This article proposes the concept of the “learning journey” to explore the relational complexity of how individuals learn at different workplace settings across their working lives. In order to illuminate this, the article draws on the learning experiences of two workers with different roles at two points in time across different workplaces. The author argues that individual learning involves a complex interaction of individual positions, identities and agency towards learning. This complexity is relational and interrelated with the workplace learning culture, which is why learning is different for individuals in different workplaces and even for the same person in the same workplace when occupying different roles.

Itinéraire d’apprentissage : conceptualisation du « changement au fil du temps » en tant que dimension de l’apprentissage sur le lieu de travail – Comprendre comment les individus apprennent au fil de l’existence en milieu professionnel est important pour nourrir les débats sur l’apprentissage tout au long de la vie à l’époque actuelle où les changements peuvent être imprévisibles et fréquents comme l’illustre la pandémie de COVID-19. Malgré le corpus de littérature existant sur « l’apprentissage », peu de recherches ou de connaissances théoriques portent sur le « changement au fil du temps » en tant que dimension de l’apprentissage individuel sur le lieu de travail. On accorde de plus en plus d’importance au développement personnel des individus étant donné qu’ils assument des rôles de médiation essentiels dans les pratiques professionnelles des entreprises. Cet article présente le concept de « l’itinéraire d’apprentissage » pour examiner la complexité relationnelle de la façon dont les individus apprennent dans différents cadres professionnels tout au long de leur vie active. Pour éclairer ce propos, l’article s’appuie sur l’expérience éducative de deux salariés avec des rôles différents, à deux moments différents, sur des lieux de travail différents. L’autrice affirme que l’apprentissage individuel inclut une interaction complexe entre les points de vue, les identités et l’action personnels en matière d’apprentissage. Cette complexité est d’ordre relationnel et liée à la culture de l’apprentissage sur le lieu de travail, ce qui explique la raison pour laquelle apprendre diffère pour les individus en fonction du lieu de travail, et que même pour une seule et même personne apprendre sur son lieu de travail diffère en fonction des postes qu’elle occupe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Learning in and Through Work: Positioning the Individual

Conceptions, Purposes and Processes of Ongoing Learning across Working Life

Learning in Response to Workplace Change

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In today’s precarious global market economy, many countries are under increasing pressure to remain competitive and productive. The impetus to be competitive usually results in changes in work organisation, work structures and the labour market. Many countries promote lifelong workplace learning and encourage innovation as necessary strategies to address these changes (Yorozu 2017 ). Although a corpus of theoretical accounts of learning exists, there has been limited theorisation or discussion of what lifelong workplace learning might entail, especially in this period of uncertainty and disruption, when career progression is less linear than in earlier times (Akkermans et al. 2020 ; Arthur et al. 1999 ).

Drawing on data from a group of in-service vocational teacher trainees enrolled in a one-year training programme run by a local university in Brunei, this article proposes the concept of a “learning journey” to advance our thinking about change over time as a dimension of workplace learning. The article follows a conventional sequence, beginning with a review of the different theoretical perspectives about learning for work to illustrate the hitherto limited emphasis on lifelong workplace learning. This literature review is followed by the research methodology. Two case stories are presented to contextualise the findings, with a discussion considering the interrelationship of individual positions, identity and agency which deepens our understanding of learning throughout working life. The article concludes by underscoring the concept of a “learning journey” to conceptualise the change-over-time dimension of workplace learning as part of individual lifelong learning and the implications of this concept for advancing our thinking on the topic.

Learning for work and lifelong learning

Most countries’ policies and standard practices take an approach to learning for work that focuses on the early stages of a career. For example, initial teacher training and/or teaching practices precede employment as teachers; new doctors need to undergo a period of internship training before entering the profession; and apprentices learn on the job. Once able to perform satisfactorily, they are employed in the job. On a similar note, mature students returning to work are assumed to have completed the necessary training prior to (re-)entering the labour market. This front-loaded model of workplace learning, as the name implies, assumes that all the essential training needed for a lifetime of practice has been completed once the training programme is complete.