Patricia Grace

Everything you need for every book you read..

The story’s narrator , an unnamed 71-year-old Māori man, leaves home to go into the city to meet with officials about the future of the land his family has owned for generations. As he waits for a taxi to pick him up, he feels annoyed by his family’s nagging: he thinks they treat him like an old man. Still, he is in a good mood, happy to be out on his own and expecting to have success in the city. Traveling to the train station in the taxi, he watches the town pass by, noticing which parts of the landscape have changed and which have stayed the same.

He enters the train station and boards the train, continuing to observe the view out the window. He notes how much development has occurred in the area since he was young: construction projects have radically changed the landscape, filling ocean with land in some areas, causing erosion, and turning farmland into housing developments. While he bitterly resents the ways that the Pakeha disrespect the land, he reminds himself that the development provides people with basic needs, such as housing, food, and transportation. When he gets off the train in the city, he remembers how, during an economic crisis in his youth, many starving people lived in the train station, but his family survived because they were able to garden on the family’s land. Outside the station, he sees a spot where the city bulldozed a graveyard to build a highway, and the narrator reflects again on the disrespectful behavior of the Pakeha. He then walks confidently to his meeting.

After the meeting, the narrator waits in the station for his train home, reflecting on the conversation with the city planner . In the meeting, the narrator explained that he wanted to subdivide his family’s lot so that each of his nieces and nephews could live on it, but the city planner responded condescendingly, telling him that the land was slated to become a parking lot in a future housing development. The narrator urged the official to reconsider, explaining that the family’s relationship to the land goes back generations, so they could not simply sell it to the city. The meeting escalated into an argument, in which the planner revealed the underlying racial discrimination of the city’s decision: having a Māori family living together on the land would decrease the land’s value. At this, the narrator became very angry and kicked the planner’s desk, damaging it, and the planner forced him to leave the office.

The narrator returns home to his family in defeat. Instead of telling them how the meeting went, he shouts at them, demanding that when he dies, they cremate him instead of burying him in the ground, as he is afraid the development project will unearth his remains . He then retires to his room alone and sits on the edge of his bed for a long time, looking at his hands.

Journey | Summary and Analysis

Summary of journey by patricia grace.

Journey is a powerful story that critiques the idea of “modernization” and relates its impact on indigenous cultures. Written in the third person point of view, the story engages with the themes of identity, change, conflict of values and the impact of modernization. The main character is an unnamed seventy-one-year-old man, who reflects on how much things have changed as he travels to the town’s government office. This change slowly begins encroaching upon his personal life, and a point is reached when his very identity and the identity of his people comes under threat.

The Journey, published in 1980, is written by Patricia Grace. She is the first Maori woman to have published a novel.

Journey | Summary

The story begins with a seventy-one-year-old man preparing to travel somewhere. He prefers to call it a ‘journey’ to maintain a sense of excitement. He uses the bathroom beforehand because he does not like public lavatories. He does not want to be thought of as an old uncle today- he can get around town just as well as a youngster. As he sits in the taxis, he thinks they smell the same, the shops passing by all look the same. He makes conversation with the driver, and then gets off at the train station. He does not want people to fuss over him- he is perfectly capable , and is happy to have a carriage to himself from where he can see everything pass by through the window. He notices that this land they are travelling on used to be the sea.

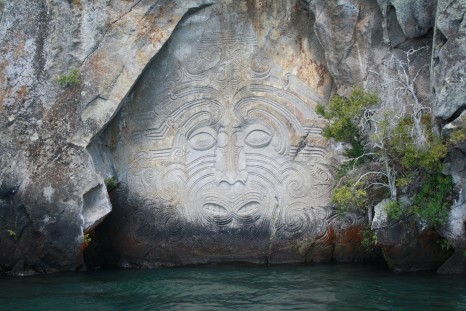

After some time, the train becomes full. He sees kids wearing ‘plastic’ clothes. Outside, the houses still look the same as they always did. As the train moves into the crowded part of town, the old man notices several new aspects- asphalt and steels and high-rise buildings. When he looks back at the children, one of them reminds him of his childhood friend , George , and he wonders how George has been. When the train ride is over, he decides that the railway station looks the same, crowded as always, and the same statue of Kupe with his woman and his priest remains in place. The marble floor he used to like is now a hindrance, as he is barely able to walk on it. The railway stations used to be full of starving people, but the old man never let such a fate fall upon his own family.

Next, time has elapsed. The old man is on his way home , with an ache on his foot. For a moment, his mind wanders to the past, when he would wait in this station and watch out for George. We then see what happened during his visit to the city’s government office- the city planners were going to build parking lots over the man’s ancestral land . The man explained to a worker named Paul that his nieces and nephews had been waiting for years, and it rightfully belonged to him, but he was told that they would all receive monetary compensation. No matter how much the old man tried to reason and argue, his efforts were futile- he was not able to understand the planner’s explanation . In frustration, he ended their discussion with a damaging kick to Paul’s desk, which had him removed from the office immediately. The flashback then ends, and the story returns to the present, as the old man is about to go back home. He is painfully aware of the ache in his foot from the kick. He wonders if he should go looking for George.

He could hear them talk about him as he exited- he is old, not deaf. In the taxi on the way home, he once again makes conversation with the driver, who can tell he is disheartened. The driver drops him off right at his doorstep, telling him to be safe and praising his garden. Finally, the old man tells his family, who were waiting with subtle curiosity to hear about the day’s events, that he wants his body cremated when he dies, rather than buried. The cemetery is no longer safe- nothing belongs to them anymore, and he does not want his remains messed with after his death. The story ends with the old man sitting down and looking at his hands in frustration, unable to do a thing more.

Journey | Analysis

Patricia Grace is a writer from New Zealand, known for making references to Maori culture and language. She is the first Maori woman to have published a novel. Her style is elegant and effective – especially as seen in Journey , where she forgoes the use of certain punctuations in order to create a tense and flowing tone . The use of stream of consciousness technique in the Journey allows the reader to gain a perspective of the inner life of the narrator. This transitioning between the subjective world of the unnamed narrator and the objective reality that he’s faced with presents a tension where, on the one hand, the memories of the narrator are under his control while on the other hand, the moment in which he lives and the material reality that his life is faced with are completely out of his grasp. This is also reflected in the constant tension created by the theme of continuity and change.

All of these elements enrich the character of the old man in the story and endears him to the reader. The reader thus empathizes with the old man’s perspective, despite the story being written in third-person. Some themes of Journey are change, conflicting beliefs and values, the implications of modernization and land-ownership . It also tackles the slight helplessness and frustration towards being ‘fussed over’ that comes with old age. The title ‘Journey ’ is important, as it might not just be literal- it is also the journey to the old man’s realization that so much has changed. It is also interesting to note that the idea of one’s ancestral land is a special and important part of Maori culture – personal land is often divided among the family for generations, forming a close bond. We may use this insight of the practice to understand the old man’s feelings during the climax of the story. Further, the historical background of Colonialism and its impact on indigenous ways of living looms large in the backdrop of the story, thus providing a great import to the idea of home and belonging to one’s land.

A recurring element, introduced in the opening, is the man’s distaste at being seen as old . “But not really so old, they made him old.”, “not what you call properly old” and “Seventy-one is all.” This also marks his independent personality- he has grown up doing everything himself, providing for his family, and being capable of even physical work. The idea that others no longer perceive him that way irks him greatly. We also see that his sharp eye for change – being able to notice what has stayed the same and what hasn’t over the years- is an attempt to feel younger and feel as though if nothing has changed externally, then he has not changed either. The Pekhas/ Pakehas (meaning white New Zealanders of European descent) think constantly about development- the man himself is heading to meet the city planners- which is something he does not approve of.

We must also note the features the old man notices in other people- the first thing he points out is whether they look young or old. The “young” cab driver, the “young” man working at the ticket counter… these are the ways in which he identifies people around him at first glance. His slight contempt towards the younger generation symbolizes his dislike towards modernization the evolution of the town and the lifestyle of the people. He believes it is the youth that facilitates the change, and this facilitates his unease towards them. When he sees a child who looks like his old friend George, he immediately feels happier- this symbolizes the joy of the past and desire to hold onto it . He also thinks, as he sits in the train, that there are “ things they don’t know, all those young people ” which gives the readers the understanding that he wants to prove his competency. Interestingly, he does not say this to anyone- it remains a thought. Through this, we realize that the main person he is trying to remind or convince may be himself . It is possible that his interactions and observations have caused a lessened confidence, which he is trying to bring back up. However, analyzing his thoughts merely as that of an elderly individual may not be as fruitful an exercise as compared to contextualizing it to the experiences of indigenous cultures who had to pay a heavy price for the idea of modernization. The wariness of the old man seen in this context doesn’t become the thoughts of a senile septuagenarian but contains within itself the mistrust of a section of humanity whose ways of living had been negated by another in the name of “change”.

Throughout the train journey, the old man pays a great attention to land. He is also meeting the city planners to discuss his ancestral land . Land is not only an important part of Maori culture, but it gives the man a sense of ownership- that as everything around him changes, this is something he is in charge of. Now, when that stability begins to shake, he feels utter helplessness on being faced with the fact that those in a position greater than his own can take away something that belongs to him and is a part of himself . It is as though they have a right over him, which is a very unpleasant thought. It makes him feel powerless, which is a recurrent aspect in the story. The feeling of powerlessness when he is not in control of his own property, when he needs help- or when others think he needs help- and when he realizes how much has evolved in front of him, thoroughly frustrates him. He mentions as he arrives at the train station that “ Their family hadn’t starved, the old man had seen to that. ”- from this, we can tell how capable he was in his youth, and more importantly, how dire the situation was. This change from being in-charge to the feeling powerless in itself is a journey- a nod to the title.

When the old man is waiting at the station, his foot hurts. This is in reference to the way he kicked Paul’s desk, as well as the natural growing pains that one experiences in old age. During his argument with the bureaucratic officers, his frustration grows at being unable to understand many of their explanations . The land has sentimental value, and the overriding of both a familial and sentimental rights represents the grand scheme of modernization. In the end, everything will belong to the city. Besides this, Paul says “ They’d be given equivalent land or monetary compensation of course. ” when the old man talks about his nieces and nephews. Here, we see the disregard of any emotional aspect by the city planners . Ancestral land is close to the family’s heart, and cannot be replaced by other land or money- it is not the literal land or finance that holds the meaning.

When Paul explains some future plans, the old man replies “ well, I’ll be dead by then” which is similar to a thought he has in the train ride. These subtle lines hint at the decreased zest for life as his abilities wear thin. Adaptability to change is an important theme in this story- the city planners have embraced it to the point of overlooking less technical detail, while the old man has a tough time even understanding it. In the end, the man is unable to regain his land, and kicks Paul’s desk in anger. This gesture symbolizes futility . It does nothing except cause a ruckus and cause pain to the man’s own leg- it does not help his case with the land in the slightest. This represents the same futility of his requests and reasoning- it will be heard, but not listened to. No matter how much he speaks and insists, he will go nowhere with it. It is similar to how the old man feels about the fast-paced evolution of the world he once knew- no matter how hard he tries to keep up, he is unable to do so. It is saddening to note the way the old man is treated, despite asking for something which he has a complete right to. It goes to show diabolic grip the societal power hierarchy has on the lives of individuals.

After kicking the table, the old man staunchly refuses to accept that he is limping . “ Going, not limping ,” he says several times. This displays an unwillingness to show any sort of weakness , mental or physical. He does not want to be “fussed over” or looked down upon. When he finally reaches home, the taxi driver compliments the garden. This garden plays a key role in the man’s life- it represents the only piece of land the old man has real control over. It is a microcosm of the word for this man, He may do anything he wants with the garden, unlike his ancestral land. He views it as something under his full control- it is necessary for him, as authority slips away in all directions, to have something to hold onto as his own. This garden symbolizes his remaining strip of true freedom the man has left for himself.

At the end of the story, he announces to his family that he wants to be cremated rather than buried because “ the cemeteries are not safe. ” This is such a powerful line and is in reference to the cemeteries being planned and structured by the city planners and the town government. Therefore, they have a right to it- having a right to the cemetery means having a right to all the tombstones, bones and remains, as well. It’s almost as if people like the old ma have no right to live and no right to die. He is adamant that nobody, least of all the town, should be able to touch his remains. For this reason, he would rather become ash. Yet as soon as he says this, he sits in his room alone, with the door closed, looking at his hands for a long time.

The ending of The Journey symbolizes solitude and defeat. The man feels alone, as though nobody understands him- and he has realized that so much has changed around him that he is no longer as efficient and knowledgeable as he once thought. It is a difficult realization to come to, one that frustrates and saddens him, and the readers equally. The story ends on a despondent note, as we are left to wonder about the old man and how he deals with this awareness, as well as feel the ache of injustice and empathy from the imagery created by Grace. The picture of an old man, alone and disheartened, sitting on the bed does not leave the readers’ minds, even as the story draws to a close. The journey, for him, has ended.

The Plantation | Summary and Analysis

Severn suzuki’s speech | summary and analysis, related articles.

The Great Hunger | Summary and Analysis

On the rule of the road | summary and analysis, the guest albert camus summary.

Antarctica | Summary and Analysis

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- My Life as a Bat Summary February 29, 2024

Adblock Detected

Academy of New Zealand Literature

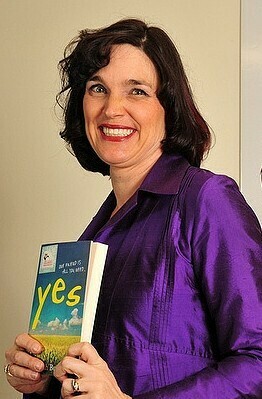

Photo credit: David White/FairfaxNZ

The Interview – Patricia Grace

Patricia Grace was born in Wellington in 1937. She was teaching and raising a family when she began entering her work in competitions with local newspapers. Her first novel, Mutuwhenua, (1978) was the first novel ever published by a Māori woman writer.

She has published a number of influential and acclaimed story collections and novels that explore Māori experience, both historical and contemporary, and her work has been widely published, translated and anthologised.

Her numerous honours include the Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement in 2006, and Distinguished Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit (CNZM) for her services to literature in 2007. Patricia lives with her whanau in Plimmerton on her ancestral land of Ngāti Toa, near her home marae at Hongoeka Bay.

This interview with Adam Dudding took place in April and May 2016, when Patricia’s seventh novel, Chappy, was a finalist in the Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

When did you realise you were a writer?

I’d always been interested in writing without really knowing what real invented writing was. From a young age I liked the act of writing, which might mean copying words or sentences from books or advertisements, or trying to write letters when my mother was writing letters. At school we copied sentences from a blackboard on to our slates. I enjoyed that but I never thought of making stories from my own experiences.

We weren’t encouraged in that either. We were given topics from textbooks from England to write about, so if we had a topic like a ‘walk in the forest’ I would write about forests I’d never been in that had brooks and bluebells in them. It seemed to be what was expected of us.

What I wrote was all from my reading, and my reading was from things like the Weetbix packet, Sergeant Dan the Creamoata Man ads, Chicks’ Own and other comics, and Whitcombe and Tombs primers which were our school readers. If given a topic like ‘A day at the seaside’ I’d write about ‘seasides’ – with the little stripy tents I’d seen in comics where you went in and changed into your bathing costumes. It never occurred to me to write about the beach where I swam and played daily in the summer holidays. I was using words in my little ‘essays’ – we had them once a week – that I’d never heard spoken, like ‘bathing costumes’, ‘meadows’, ‘briny’ – all those kinds of words. We might have heard the word ‘forest’, but we’d usually referred to our own forest as the bush. Real forests, to my understanding, were inhabited by wolves, foxes, woodcutters and all kinds of magic animals.

Who are the writers who influenced your writing, or informed your decision to be a writer in the first place?

So, in the early days I didn’t know what real creative writing was. I thought it was just imitating what had been read. I don’t know – trying to write a new Conan Doyle-type mystery, cobblestone streets, or something like that. That was until I came across writing by New Zealand writers, which was very late – after I’d left secondary school. I started to hear the New Zealand voice in literature and to understand that real writing is writing that comes from your self – your dreams, imaginings, emotions, dreads, desires, perceptions – what you know. Part of what you know comes from the research that you do.

Those early influences were people like Frank Sargeson and Katherine Mansfield. I started to experience the New Zealand settings, hear the New Zealand voice in what I was reading for the first time, and then when I came across the writing of Amelia Batistich, a New Zealander of Dalmatian origins, I thought well, this is a different New Zealand voice. It started to click with me that I might have my own voice too. The penny dropped rather late for me.

As well as Batistich there were all the Maurices [Gee, Shadbolt, Duggan], as well as writers like Dan Davin, Robin Hyde, Ruth Park, Ian Cross, Marilyn Duckworth, Janet Frame. All added to my enlightenment and to the realisation that I would have a voice of my own. I knew also that there were people who I could write about, or characters I could invent, based on people I knew, who hadn’t really been written about before. There were stories about them, but not written ones.

How old were you?

Early 20s. I was waking up to what writing was during my teachers’ college days, and after that.

In 1975 you became the first Māori woman to publish a collection of short stories. Apart from the absence of role models and predecessors, and the fact that you’d been raised on brooks and meadows, did you encounter specific barriers that you mightn’t have if you’d been Pakeha, or male, or both?

I wasn’t aware of any. I think the time was just right for myself and for people like Witi Ihimaera and Hone Tuwhare. The real pioneers were JC Sturm, Rowley Habib, Arapera Blank, Rose Denness and Mason Durie and those writers I had started to see published in the journal of the Māori Affairs Department, Te Ao Hou.

But I have to say that once I understood what writing was all about, the real influences were the people around me – parents and brother, cousins, aunts, uncles, grandparents of the extended family. It was not so much because of the anecdotes they told but because of who they were, what they did, what they said and how, and how they interacted with each other, how we all interacted. My parents delivered some very intriguing one-liners which fired the imagination, such as: ‘You know, you had an uncle who rode on a whale.’ Or, ‘Your great-great-grandfather had two rows of teeth, top and bottom, and he used them when he climbed ships’ masts.’ Later, my husband’s family were also influential – great storytellers, great orators.

Once you’d found your voice, which parts of the writing life did you find you loved, and which were just a slog?

The slog is getting from the beginning to the end. The good part is going back and sorting everything out and doing the editing. That’s the part I really enjoy – knowing that everything is almost there and that I can get to work and rearrange or refine. I could go on doing that forever – you have to call a stop to it somewhere along the line.

I also love the research. I never used to do much research in the early days but in my more recent novels there’s been quite a lot. I probably do much more than I need to do, but doing much more than you need probably helps put everything in a fuller context.

I really love it when I’m writing and you get these areas when everything flows. That’s a good feeling. But I also don’t mind the struggle. Sometimes I have to put something aside because it’s not working and then I have it on my mind and stay awake at night working it all out. When I do work it out it’s satisfying.

I have a confidence now that I didn’t have in the early days, when I’d sometimes think ‘This is too terrible. I’m never going to be able to do this.’ I never feel like that now. I know there’s always going to be a way, or that you can just chuck something out if it’s too annoying. That’s a solution as well.

I’ve heard you say you’re not very technologically minded, but did the availability of computers from the 1980s on change that editing process that you enjoy so much?

Yes, though because I wasn’t brought up with computers I still always start off with handwriting, then I go on to the computer. It’s a wonderful tool.

I started using a computer when I was writing Potiki (1986) I think. I wrote it all in longhand, and I cut it up and stuck it back together with sellotape – the real cut and paste – and then typed it up on my Brother portable typewriter. I think I put it on to computer when I took up the fellowship at Victoria University in 1985 and there was a computer available to me. Vic Uni has the manuscript in its archive. They displayed a few pages of it, I think it was in 2012 or 2013. It was all handwritten on the back of old computer paper, and one of the pages they decided to show had a bit of a shopping reminder scribbled on one corner. It was after the publishing of Potiki that I was given a computer by Digital Equipment. They were giving away a computer each year as a way of supporting the arts. They’d given one to Tom Scott the year before and asked him to recommend someone. He recommended me. We’d never met but I was grateful.

Some of your most enjoyable writing is your dialogue, especially passages where you capture numerous people talking at once. I’m thinking the guys in the pub betting on horses in ‘Dream’ [ Waiariki ] or the kids playing bullrush in ‘Kepa’ [ The Dream Sleepers ]. Can you talk a little about how you capture that stuff? Are you scribbling on your shirt sleeve or pulling out a tape recorder? Do you just have a great memory? Where does all that talk come from?

I find dialogue the easiest of all, something that just flows. It comes from my own experience of being a kid, or listening to kids or being interested in what people say and how they say it. It’s because of having several registers within myself, which we probably all have, and making use of them. I remember the funny things that people say – or for that matter the striking or ordinary things that people say. No I don’t take notes or use a recorder. I can pull dialogue out at any time, Always had it in my head, all my life. I wasn’t a very talkative child and I’m not a greatly talkative adult even, but I do enjoy listening to people, and language and how it’s used. It becomes part of my own store. It’s enjoyable getting into a piece of flowing dialogue.

Several of your novels, the later ones especially, are sagas – lots of characters, lots of event, long timeframes. Do you map out these more complex narratives in advance or just follow your nose?

I don’t map them out, because I don’t seem to be able to work that way.

When I started Potiki I thought I was writing a short story. I wrote the story about the carved meeting house, and when I finished that I thought if we have a meeting house there are people who belong to that meeting house. I asked myself who they might be. I started off with one character – that was Roimata – and how she came to be there, in that community. And then her children one by one, and her husband. I didn’t know from one chapter to the next what was going to happen – I was just following. That’s what I like to do. I just start out and follow the characters.

You gave me the opportunity before to say what was the best part of writing. The main thing for me is characters. I don’t really worry about anything else. I don’t think about the storyline too much actually – just the characters and what might happen to them because of who they are and where they are and who they interact with. The settings, the stories, the themes and the voices and everything else, the inter- relationships – all belong to the characters. So if you keep true to those characters and how they might develop because of who they are and who they have around them and, to a degree, what happens to them, then the story will unfold. I’ve learned to have faith that something will come out.

I didn’t know from the beginning to the end of Potiki what was going to happen. I had to go back and match the beginning up to what happened at the end. That’s the most extreme example of how it has worked for me. But it’s been a bit like that with all of my books.

With Chappy (2015) I knew the little story told to me by my husband about the Japanese shopkeeper in Ruatoria, where my husband was from, who was married to a local woman, probably a relative of my husband’s. My husband had told me how well-liked the man was in Ruatoria, how he was taken away to Somes Island during the war, interned as an enemy alien and was later deported, leaving his wife and family in Ruatoria.

I was very taken with that story, but at the same time I knew I wasn’t going to be able to get inside the head of a Japanese man, understand him culturally, or know his psyche. I had the core of a story but I didn’t know how I was going to tell it, how it would unfold. I couldn’t tell it from the inside, so I had to tell it from the outside. I had to choose the narrators, but I didn’t quite know who they would be. They had to present themselves.

When I heard the story I kept wondering how the Japanese man got to be in that Māori community and to be part of it. My husband was unable to tell me so I had to make up my own way of getting him here (my character, not the real one) and in thinking about that, came across the character of Aki, the seaman. I had an uncle in the family who had gone to sea at a young age.

Is that the same uncle who’s in your 1975 story ‘Kepa’, the one about the kids who are playing bullrush and waiting for their uncle to return from his faraway travels?

Yes. They’re based on the same person. He was an impressive man when we were kids – this uncle who was going to bring us home a monkey from overseas. I knew some of the ships my uncle had been on so I looked those up in my research. I knew he was on the boats during the war too.

So that was that voice. And then I wanted someone who didn’t know anything about Chappy, so I brought in the grandson – who had to come from far away.

So the grandson who’s raised in Switzerland got pushed to the other side of the world by you to ensure his ignorance of Chappy’s story?

Yes that’s right. I had to have someone who didn’t know, so he could find out. And I needed Oriwia as well, Chappy’s wife, grandmother of the young man from Switzerland. I needed her because the uncle was away at sea. He knew how Chappy got there but there were aspects of his new life that Aki was not aware of.

People need to inhabit the work. I’ve always been interested in writing about those interrelationships – especially the intergenerational ones. It’s a matter of finding ways of doing that which enable different characters to have clear identity.

Storytelling is one way I’ve found very useful – having different characters telling about the same things, each one bringing a new aspect and further enlightenment to the accounting.

‘The main thing for me is characters. I don’t really worry about anything else.’

If you find the story by following the characters, how does that work in a novel like Tu, where there are revelations and plot twists right near the end which have been set up early in the book. Did you always know the twists were coming and what would happen to Tu in battle, or did you have to go back like you did with Potiki , and tweak the beginning to match the ending?

With Tu the twists came to me as I wrote. My idea was to have three brothers going off to war but I didn’t know what was going to happen to any of them. Well, I had a vague idea. I like vague ideas that can rattle around in my head, but which are not too fixed.

My task at the beginning was to make each brother different. So I had the older brother with all his heavy responsibilities after what had happened to the father; the next one who was the opposite; and the youngest one who was kind of the hope of the family – the one to rise above the situation they were in, who was protected from the father, who was to be well educated and have advantages which would mean best opportunities and a better life.

The idea that the older brothers wanted the younger brother to be protected – a lot of that came from reading the official history of the Māori Battalion and other material – there were many examples of older brothers not wanting their young brothers to go to war because of the tukana/teina relationship and the cultural demand that the older brother be responsible for the younger one. But the big brothers knew that in theatres of war they wouldn’t be able to look after their teina. They didn’t want the younger brothers to go.

There was one story told by the padre for the Māori Battalion. His younger brother had come to war against his wishes, and he prayed every day that if one of them was to not go home that it would be himself, not his younger brother. He would not want to go home if he was to leave his younger brother behind.

There were other efforts by soldiers, who’d pleaded with their superiors not to accept their younger brothers, or to send them home because they’d put their ages up and they shouldn’t be there and so forth. But of course with the loss of numbers during battles, and the need for replacements, hardly anyone was turned away.

Those stories and anecdotes, from my research, were very impressive, so in some ways the stories in Tu were not difficult. I just had to think about how the two older brothers were going to get the younger one home again. I knew from the beginning that Tu was going to be saved but I hadn’t worked out how. I didn’t know what his life was going to be after the war and had some decisions to make when I came near to the end.

Paula Morris keeps saying Tu needs to be turned into an epic movie. Do you have any films of your work on the way?

The book Cousins has been in the pipeline for years and years, and I’d sort of given up hope with that, but it has recently come forward again, so we’ll see what happens there.

There was an option on Tu , and a discussion about Dogside Story . Barry Barclay had wanted to do Potiki . But they’ve never really come to anything, possibly because I was less than enthusiastic. I’m not holding my breath really, about the books becoming films.

I’ve seen, but not really understood, some pretty dense academic analyses of your work, with references to everything from Baudrillard to your use of ‘spiral’ form. How do you feel about academic slicing and dicing and labelling of your work, and do the things people say about your work often match what you thought you were doing?

Not always, not often. However, I do appreciate the scholarship, and the efforts that scholars make to unlock the work, especially where it may lead to societal enlightenment. Much of it is over my head. I read reviews, and if they say great things that’s good and if they don’t it doesn’t matter. You write and you do the best you can. You put the work out there, and everything else that happens after that is beyond your control. I’m pleased if the book’s being read. Beyond that comes interpretation and discussion – the third life of the book – and I think that’s all good.

The spiral thing though – I have tried to explain before how I position myself in the writing. I don’t have a sense, when I begin a new work, of standing at the beginning of a long road and looking along it to an end. Instead I have a sense of sitting in the middle of something – like sitting in the centre of a set of circles or a spiral – and reaching out to these outer circles, in any direction, and bringing stuff in. That’s what makes it all closer to me, being in the centre and having all I need within reach around me and piecing it together. So there I am, at the core, with my core idea – the few sentences about the Japanese man – thinking about what I need to bring this character to life and to shift him from A to B.

Writing from the centre of a circle – is it silly to suggest this could be a specifically Māori sensibility, and the straight road is a linear, Pakeha kind of thing? Or is that just stereotyping both Māori and Pakeha worldviews?

I don’t know. I don’t know how other writers see themselves placed. I just know that I have to have a sort of nearness to everything and if it’s not near I need to bring it near – that’s when I do research.

Some of the stories in your first collection, such as the story of the fisherman Toki, have a curious, poetic syntax, with the words in an unusual order for English. I was guessing that might be a transliteration of Māori syntax. Is that right, and if so, why did you do that?

Yes. It was a contrived style in a way, but I was trying to copy Māori structures in English, to make it seem as though the characters could be speaking in Maori, even though I was writing in English. It was experimental. It might appear here and there in later work as well, but it had too contrived a feel for me after a while, so I didn’t keep it up.

I believe you’re not a fluent speaker of Te Reo. Is that right?

No I’m not. I didn’t learn very much when I was a child because the adults who were fluent speakers of Māori around us wouldn’t speak it in front of us. I didn’t even know that that was my grandmother’s first language. The only time I heard it spoken would be at a tangi during formalities – and those experiences were quite rare. We had Māori words that we knew and used but that was all really. It wasn’t a Māori speaking community.

It wasn’t till my teenage years I started to take an interest in the language itself. I’d always had the idea that it was not a useful language, and had even heard it said that it wasn’t a proper language because it had ‘no grammar’. But then I met young people at teachers’ college who could speak Māori, who came from Māori communities, who didn’t have any trouble with English, and seemed to thrive from having two languages rather than only one. I started to feel that loss.

I made some efforts to learn but I haven’t been that successful. My children have learned but I’ve found it quite difficult. I can understand much more than I used to, but I’m very timid about trying to use it.

As for using it in my books – we just grew up using certain Māori words in English sentences so that’s what I’ve used in my writing. It’s because I wanted to be true to the characters and the way they spoke, not from any sense of wanting to alienate readers, which I’ve been accused of. I don’t think anyone would want to do that.

But I understood that you’d made a deliberate decision not to put a glossary of the Māori in Potiki, which is the thing that reviewers considered alienating. Is that true?

So guilty as charged in that instance?

Well yes, but I don’t feel guilty. When Potiki first came out there was quite a bit of criticism of it. One of the reasons was because of the use of Māori terms and passages in the book; the other was that some people thought I was trying to stir up racial unrest. The book was described as political.

I suppose it was but I didn’t realise it. The land issues and language issues were what Māori people lived with every day and still do. It was just everyday life to us, and the ordinary lives of ordinary people was what I wanted to write about, so I didn’t expect the angry reaction from some quarters.

But there was one deliberate political act, and that was not to have a glossary for Maori text or to use italics. A glossary and italics were what were used for foreign languages, and I didn’t want Māori to be treated as a foreign language in its own country. When I told my publishers I didn’t want the Māori italicised or glossed, and gave my reasons, they agreed with me.

I’ve not read Potiki recently, but when I flicked through the pages looking for the alienating Māori words I didn’t see all that many. There are some short stretches of song that you can skim over, and occasional ‘haeremai’ or ‘karakia’ or ‘whanau’ which most Pakeha understand these days anyway. These would be totally unremarkable in a book published today.

Yes, but nobody knew them then. Since Potiki I’ve not come across any negative comments regarding the use of the Maori language in texts, except when one of my books was shortlisted for an Australasian prize, and it came back to me that mine was strongly rejected by the Australian judges because of the Māori language and no glossary – though that may not have been true.

One difficulty I have come across is that sometimes there’s a word that, if it isn’t glossed or italicised, you’d just think was an English word. ‘Mate’ means sickness or death but it just looks like the English ‘mate’. So I avoid words like that.

You have a knack for picking out the ironies within the politics, such as in the story ‘The Journey’ where an old man is saddened by Pakeha ‘progress’ but notices that the digger drivers are all Māori. Do you ever feel a tension between the artist’s desire to be nuanced and aesthetic even if it undermines the polemic, and the activist’s desire to shout from the rooftops about injustice?

I don’t think there’s a tension. It’s just however it comes out. Sometimes, quite often, I have to pull back rather, because politics can be overdone. You don’t want your work to become a drag. Rereading and editing you find what needs to be there and what doesn’t.

From the casually racist Pakeha woman in 1975’s ‘A Way of Talking’ onwards, you have drawn many vivid little vignettes of everyday racism. Have you personally experienced much of that yourself?

A lot of it’s from personal experience. When I was a child, and I think even now, you come across something every day that you might find disagreeable, and mostly you just put it behind you. If you can make a difference or say something about it then you do, but if you think it’s going to be a waste of time you don’t bother.

But I feel our race relations are good in this country, even though not perfect. There’s a level at which we all get on and really care about each other. But there’s also a level to do with the politics of the country, where elements of racism are brought into play for political reasons. Learning about each other is not as one-sided as it used to be.

Those overt, quasi-official examples of racism you’ve written about – you can’t come into this cinema because you’re Māori; you can’t get a home loan because you’re Māori; you get a smaller widow’s pension because you’re Māori – they’re starting to feel like the distant past aren’t they?

Yes, but not the too-distant past. We’ve all worked very hard on those things over the years, but we need to be mindful. There is still much that is discriminatory in our institutions and workplaces which affect the powerless. Statistics will tell us there’s still a way to go.

Which of your works are the most explicitly autobiographical?

In the short stories, it would be ‘Going for the Bread’ ( Electric City , 1987) which is just completely a story about what happened – there are hardly any changes at all to something that happened to me when I was about five years old. And for a novel, I would say Cousins (1992).

You’ve kept swapping between novels and short story collections. Novels often get more kudos, but do you place more value on one rather than the other?

I’ve always loved the short story form. Short stories are like little gems that you can keep polishing and polishing in your aim for perfection.

When I’m in the mood to get my teeth into something I’ll go for the novel, but there’ll always be a short story hanging around that I might start, and when I have enough starts I come up with a collection. I don’t think one form is superior to the other.

When you write the first word of something new do you know whether it’s going to be a short story or a novel?

I usually know when something’s going to be a short story. Potiki is the only ’short story’ that’s turned into a novel, really.

Going back to when I first started writing, there are several little stories about Mereana dotted through the first three collections. I had the idea that they might be a novel, or if not a novel, a collection of stories that formed a whole story in themselves, but that never worked out.

I’d not even heard of the Neustadt Prize before researching for this interview, but it turns out it’s a huge deal. A US$50,000 prize that some people have described as America’s equivalent of the Literature Nobel. How did it feel to win it in 2008, apart from the pleasure of getting a fat cheque?

Well, I was amazed, because I hadn’t heard of it either. The way the judging is done is that different academics take a book that they think would be a worthy recipient of the prize. They meet and read each other’s choices and judge them and talk about them, They advocate for their own choices, but finally come up with the one they all agree on to be awarded the prize.

Joy Harjo of the Mvskoke/Creek nations – writer, musician and academic – and who I had met, rang me one day and said that she had entered Baby No-Eyes (1998) for the Neustadt Prize. She said it was an international prize and that she was one of the judges. She explained to me how it all worked and I was saying ‘Oh thank you very much for that. I hope it doesn’t give you too much stress…’, thinking that it was all still in the pipeline. And she interrupted and said ‘… and it won.’ So it was an enormous surprise.

I went to Oklahoma to collect the prize and met the benefactors of the award. I didn’t realise it was such a big deal really. I was very proud to have won it. There’s been only one other nomination from New Zealand, when Bill Manhire put one of Janet Frame’s books forward, but unsuccessfully. I think we should have more nominations from here.

Your stories have found audiences here and abroad. Do you ever think about who your reader will be as you write?

No. I don’t like the feeling of anything that’s limiting to me, such as directing my work towards a particular group. I just think my audience is people who will read, whoever they may be.

Forty years after a published Māori writer was a rarity, it seems to me that what interests the outside world most about New Zealand culture nowadays, apart from Hobbity scenery, are the stories from or about Māori: books by you or Witi Ihimaera or Keri Hulme; films like Whale Rider or Once Were Warriors or Boy . Even The Piano or The Luminaries hark back to that early colonial contact. Is it pleasing for you that Māori voices and stories are being heard strongly beyond New Zealand?

Yes it is pleasing, and I’m aware of that too. Though sometimes you wonder what is heard. I have a feeling that there are stereotypes out there and some of the work that’s reaching out may be strengthening those stereotypes. The warrior image. The haka. In Once Were Warriors there’s the image of the male dominance and the brutality and so forth. I know that that had an impact on a lot of people, and you don’t know if there’s enough out there to balance that. There could be negative images, there could be romantic images, and you don’t quite know what it all adds up to if there’s not enough about ordinary Māori daily life. You don’t know if your own work is setting up new stereotypes.

Adam Dudding is a feature writer from Auckland. His memoir about his father, the influential editor Robin Dudding, will be published by VUP in November 2016.

Photo credit: Kelly Ana Morey

'...we were there as faith-based writers, as believers in the mana of Oceania...' - David Eggleton

Patricia Grace

Patricia’s books (6).

FROM THE OXFORD COMPANION TO NEW ZEALAND LITERATURE

Grace, Patricia (1937– ), novelist, short story writer and children’s writer, is of Ngāti Toa, Ngāti Raukawa and Te Āti Awa descent, and is affiliated to Ngāti Porou by marriage. She has gained wide recognition as a key figure in the emergence of Māori fiction in English since the 1970s (see also Heretaunga Pat Baker, Keri Hulme , Witi Ihimaera , Bruce Stewart , June Mitchell). Her work, expressive of Māori consciousness and values, is distinguished also for the variety of Māori people and ways of life it portrays and for its resourceful versatility of style and narrative and descriptive technique.

Born in Wellington, Grace was educated at St Anne’s School, St Mary’s College and Wellington Teachers’ Training College, later gaining Victoria University’s Diploma in the Teaching of English as a Second Language. At Teachers’ College, she began to seek out books by New Zealand authors, including Frank Sargeson , Janet Frame and Amelia Batistich: ‘when I first read some of her stories it came home to me [that] writing was a question of voice and truth, and of a writer finding his/her own way of telling. Grace was a New Zealander with a different voice’ (interview with Jane McRae in In the Same Room , ed. Elizabeth Alley and Mark Williams, 1992). She began writing at about 25 while teaching in North Auckland, being published in Te Ao Hou and the NZ Listener, and continued to write while teaching, raising her family of seven children and moving to Plimmerton, near Wellington, where she still lives. Her first book, Waiariki (1975), the first short story collection by a Māori woman writer, won the PEN/Hubert Church Award for Best First Book of Fiction. The collection is shaped so as to find for Māori, in the words of the first story’s title, ‘A Way of Talking’, and to ‘show who we are’. This is the task given by an elder to the narrator of the final story, ‘Parade’, and stands almost as an artistic credo. The collection may be read as a progress from the almost autistic inarticulateness of the schoolgirl Hera in ‘A Way of Talking’ to the confident choric harmony of the canoe chant in Māori with which ‘Parade’ ends. The opening and closing of the volume thus establish a meticulous though unobtrusive patterning: this careful craft remains characteristic. The ten stories between elaborate the affirmation of a people’s right to speak, each with a narrative voice that is distinctively different, yet distinctively Māori, whether formally oratorical or racily colloquial. Though Grace’s style has often been described merely as ‘simple’ or ‘lyrical’, she has successfully shown that ‘a Māori world is not limited and Māori people are as diverse as any other people.’ While not the only writer to make narrative use of the Māori oral tradition, Grace’s sheer range is instantly impressive. She has continued to extend it. Her first novel, Mutuwhenua: The Moon Sleeps (1978), tells the story of the love and marriage of a young Māori woman and Pakeha man, the first time this had been done from the Māori perspective and by a Māori writer. It is focused on the effort of Ripeka/Linda to find identity as well as love, as increasingly she commits herself to her Māori being, family and name. The novel ends with her passing the couple’s baby to her mother to be brought up in the extended family, so that the effort of what Grace has called the ‘very, very large leap’ of cross-cultural adjustment is asked of the husband, whereas ‘Most often it’s the Māori people who have to go across the gap’ (McRae interview). His love and moral quality are tested and judged in those terms: ‘I went to him confidently. He had not once failed to love.’ While committedly Māori, Mutuwhenua is pointedly positive and non-polemical, emphasising ‘the common ground that all forms of life have in this country,’ with ‘stereotypes skilfully flicked aside’ (Patrick Evans, Landfall 128, 1978). Its writing also demonstrates a remarkably sensitive ear, with phrases often cadenced and paragraphs almost scored musically, for instance in the rhythmic Eliot-like prose poems which describe the city, or the several evocations of the sea shore. (Every Grace book has included variations on this aural depiction of the sea meeting the land.) Grace is acutely conscious of sound, subtle in onomatopoeia, and imbues even visual description with a strong aural quality. The stories in The Dream Sleepers and Other Stories (1980), her second collection, extend the diversity of Māori voices and aspects of Māori life, including some robustly sketched children and two memorable mothers—the comic-maverick car-toting mother of ‘It Used to be Green Once’ and the elemental, mythic yet very human mother of ‘Between Earth and Sky’, a three-page monologue which has rapidly become an iconic New Zealand text. Always writing well of children, Grace in the early 1980s wrote increasingly for them, seeking to add to the ‘few stories that Māori children see themselves in and that reflect their lives.’ The Kuia and the Spider / Te Kuia me te Pungawerewere (1981), illustrated by Robyn Kahukiwa, which tells of a spinning contest between the elderly Māori woman and the spider of the title, won the Children’s Picture Book of the Year Award. Watercress Tuna and the Children of Champion Street / Te Tuna Watakirihi me Nga Tamariki o te Tiriti o Toa , also illustrated by Kahukiwa, emphasises society’s multiculturalism, and was also published in Samoan. Grace has also published a third children’s book, The Trolley (1993) and several Māori language readers, Areta and the Kahawai/ Ko Areta me nga Kahawai (1994). The collaboration with Robyn Kahukiwa then produced Wahine Toa (1984), Grace’s text complementing the book-form reproductions of Kahukiwa’s striking paintings of the women of Māori mythology. ‘We decided to personalise the stories realising more and more that the stories are both contemporary and ancient.’ In 1985 Grace held the Victoria University writing fellowship, gave up teaching and completed her second and most successful novel, Potiki (1986), which won the New Zealand Book Award for Fiction and was third in the Wattie Book of the Year Award. In many ways, it is a synthesis of the skills developed in the earlier work (including the children’s writing), with carefully crafted cadences and aural effects unifying the prose, and evoking not only the people’s diverse individual voices and the sounds of their environment but their harmony with it and each other. Potiki has been translated into several languages and in 1994 won the LiBeraturpreis in Frankfurt, Germany. The more aggressive political stance struck many reviewers, John Beston commenting that Pakeha readers find themselves charged ‘not with past and irremediable injustices, but with continuing injustices’ ( Landfall 160, 1986). Their embarrassment (in Hera’s word from ‘A Way of Talking’) extends to the inclusion of much untranslated Māori, especially the ending, and the absence of a glossary. In Potiki as earlier in ‘Parade’ Grace disempowers the reader who can read no Māori at crucial points within the cultural form of fiction in English. Potiki makes more evident how subtly subversive a writer she habitually is. Her third collection, Electric City and Other Stories (1987), adds to the group of stories in The Dream Sleepers , centred on the girl Mereana, which Grace originally thought ‘would add up to a novel, but they didn’t’. The volume’s more successful stories are the darker adult ones, such as ‘Hospital’, with its harsh, hallucinatory version of childbirth and surgery, and its close on a despondent and aimless journey (‘not to know what’s round this bend, the next, the next one after that’), thus ending where Cousins begins. Grace’s third novel, Cousins (1992), followed Selected Stories (1991). In what may now be seen as a characteristic shaping principle, it moves from that initial wandering journey, silent, blind and objectless, to the vocal, visionary, firmly rooted communal harmony of the ending, with its sense of membership and continuity even in the face of death. The Sky People (1994), her fourth story collection, is more explicitly and consistently concerned with the disoriented, dispossessed and despondent—‘The Haurangi, the Wairangi, the Porangi—those crazy from the wind or what they breathe, those crazy from water or what they drink, those crazy from darkness or depression’ (prefatory epigraph from ‘conversation with Keri Kaa’). From sisters damaged by childhood abuse by their famous and respected father to a teenage boy tipped into suicide by sexual jealousy and its consequences, these stories refute any suggestion that Grace sentimentalises relationships among Māori. Some are political, like the zestful Swiftian satire ‘Ngati Kangaru’ (in which Māori from Australia reverse colonisation by appropriating a luxury weekend residential development), some are half-jocularly mythical, like the racy retelling of Māori creation myth in ‘Sun’s Marbles’, and some are realistic and sympathetic sketches of people on the margins of society. The writing is versatile and self-assured, and the stories stronger and more often surprising than before; several (‘Flower Girls’, ‘The Day of the Egg’, ‘My Leanne’) end with a dramatic twist or punch. The title story, about a group of people who live by re-making rejected clothes in a Wellington attic, shows a developed skill in combining entertaining storytelling with a telling underlying significance. It also (with others in this collection and earlier) illustrates a paradox that frequently sustains Grace’s art—stories of loss, isolation and sadness which yet are bright with colour, stories where the details of life’s sights and sounds tumble out in vivid lists, and where a childlike innocence and insight intersect with the most knowing adult awareness. Patricia Grace has won enthusiastic recognition among non-Māori readers, was awarded the Queen’s Service Order in 1988 and an honorary DLitt of Victoria University in 1989. She makes a significant early statement of her artistic aims in Tihe Māori Ora, ed. Michael King (1978). Significant critical discussion includes Rachel Nunns, Islands 26 (1979), John Beston, Ariel 15 (1984), W.H. New, Dreams of Speech and Violence (1987), Mark Williams, Journal of New Zealand Literature 5 (1987), the OHNZLE, ed. Terry Sturm (1991), and Roger Robinson in The Commonwealth Novel in English Since 1965 , ed. Bruce King (1991), and the C entre for Research into New Literatures in English Reviews Journal (New Zealand issue, 1993), which also reprints the interview with Jane McRae.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

In 1986, Patricia Grace published her novel Potiki , within which she discusses issues surrounding settler land appropriation and the preservation of the Māori culture. Grace was awarded third place for Potiki at the Goodman Fielder Wattie Book Awards, and in 1987, the novel won the New Zealand Book Award for Fiction.

The Trolley , written by Patricia Grace and illustrated by Kerry Gemmill, picked up the 1994 Russell Clark Award for Illustration.

Baby No-Eyes (1998) is a novel that merges controversial actual events with heartfelt family history, using different voices to interweave family mysteries with contemporary Māori issues. Among these voices are those of a deceased baby who becomes a ‘real’ person in order to interact with family members, and Granny Kura, who tells her story against a background of land occupation.

In Patricia Grace’s novel Dogside Story (2001), the power of the land, the strength of whānau, and the aroha of the community are powerful life-preserving factors. As the narrative unfolds, however, it becomes apparent that there is conflict within the whanau, which reaches breaking point as the new Millennium approaches. Dogside Story won the 2001 $15,000 Kiriyama Pacific Rim Book Prize for fiction, an award that was announced at the 14th Annual Vancouver International Writers Festival in Canada.

Dogside Story 's run of critical acclaim continued in 2001, when it was longlisted for the prestigious Booker Prize. It was also shortlisted in the 2002 Montana New Zealand Book Awards. Dogside Story was reissued by Penguin Books in 2005. Kelly Ana Morey reviewed that, in Dogside Story , Grace had created ‘...a magnificent hui of a book that bubbles over with laughter, human frailty, hope and love’ (NZ Listener).

Patricia Grace's next novel was Tu , published by Penguin in 2004. With this narrative, Patricia Grace explores the often terrifying and complex world faced by men of the Māori Battalion in Italy during the Second World War, drawing on the war experiences of her father and other relatives to write an authentic fiction about Māori soldier Tu. As the sole survivor of his family’s campaign, Tu must come to terms with what really happened as the Battalion fought in the hills and valley of Italy – and the truth is contained within the pages of his war journal. The novel received the Deutz Medal for Fiction and Montana Award for Fiction at the 2005 Montana New Zealand Book Awards. It also won the 2005 Nielsen Book Data New Zealand Booksellers' Choice Award.

Patricia Grace was honoured as a living icon of New Zealand art as part of the second biennial Arts Foundation of New Zealand Icon Awards in 2005.

She also wrote 'Moon Story' for the anthology Myths of the 21st Century (Reed, 2006).

In 2006, Grace was awarded $60,000 for fiction at the Prime Minister's Awards for Literary Achievement. Prime Minister Helen Clark said, 'Patricia Grace’s work has played a key role in the emergence of Māori fiction in English. A writer of novels, short stories and children’s fiction her work expresses Māori consciousness and values to a wide international audience.' The annual Prime Minister’s Awards for Literary Achievement recognise writers who have made a significant contribution to New Zealand literature.

As part of the Queen's Birthday Honours list in 2007, Grace received a Distinguished Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for her services to literature.

Grace was named the 2008 laureate of the US$50,000 Neustadt International Prize for Literature. The honour, administered by the University of Oklahoma and its international magazine World Literature Today , is judged by an international jury and widely considered to be the most prestigious international literary prize after the Nobel. In announcing the 2008 Neustadt laureate, Robert Con Davis-Undiano, Neustadt professor and executive director of World Literature Today said: ‘This award is a landmark recognition of an indigenous writer and gives a strong sense of the direction of important literature in the 21st century.’

Grace beautifully writes a true story of love in wartime and in peace in Ned and Katina (Penguin, 2009).

Patricia Grace was the 2014 Honoured New Zealand Writer at the Auckland Writers Festival.

Grace's novel Chappy - her first novel in ten years – was released in 2015. It follows the story of a young man (Daniel) who is sent back to New Zealand to reconnect to his Māori culture and ancestry. In Aotearoa, he discovers his ties to a Japanese grandfather (Chappy), to his local whānau, and to other Pacific peoples, making Chappy a powerful demonstration of the ties that Māori have with the wider world. The novel was a fiction finalist in the 2016 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

Haka and Whiti te Rā! were published by Huia Press in September 2015. Haka is Grace's retelling of the story of the great Ngāti Toa chief Te Rauparaha and how he came to compose the haka 'Ka Mate, Ka Mate'. It was also released in a te Reo edition, Whiti te Rā!, translated by Kawata Teepa. Both editions are illustrated by Andrew Burdan. Haka was a finalist for the Picture Book Award and Whiti te Rā! won the Te Kura Pounamu Award at the 2016 New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults.

Grace's novel Cousins was made into a feature film in 2021, directed by Ainsley Gardiner and Briar Grace-Smith, with a screenplay by Briar Grace-Smith.

Grace's memoir From the Centre: A writer's life was published in May 2021 by Penguin Random House, and followed by a book of short stories, Bird Child & Other Stories, in January 2024.

- Biography: Brittanica

- Profile: ANZL

- Interview: ANZL

- Profile: Huia

- Interview: Radio New Zealand

- Interview: e-Tangata

- Profile: Wellington Writers' Walk

- Interview: Nine to Noon

- Interview: The Guardian

Related writers

The Sitting Bee

Short Story Reviews

- Patricia Grace

Between Earth and Sky by Patricia Grace

In Between Earth and Sky by Patricia Grace we have the theme of struggle, happiness, connection and freedom. Taken from her The Dream Sleepers collection the story is narrated in the first person by an unnamed female narrator and after reading the story the reader realizes that Grace may be exploring the theme of struggle. […]

Beans by Patricia Grace

In Beans by Patricia Grace we have the theme of hard-work, enthusiasm, innocence, independence, gratitude, nature and appreciation. Taken from her The Dream Sleepers collection the story is narrated in the first person by an unnamed boy and the reader realizes from the beginning of the story that Grace may be exploring the theme of […]

It Used to be Green Once by Patricia Grace

In It Used to be Green Once by Patricia Grace we have the theme of shame, appearance, poverty, pride, good fortune and change. The story itself is a memory piece and is narrated in the first person by a woman who recalls events from her childhood and from the beginning of the story it is […]

Going for Bread by Patricia Grace

In Going for Bread by Patricia Grace we have the theme of fear, bullying, ignorance, anger, racism, conflict, struggle and love. Narrated in the third person by an unknown narrator the reader realizes from the beginning of the story that Grace may be exploring the theme of fear. Mereana is afraid to walk down the […]

Journey by Patricia Grace

In Journey by Patricia Grace we have the theme of change, powerlessness, frustration, responsibility and acceptance. Narrated in the third person by an unnamed narrator the reader realises after reading the story that Grace may be exploring the theme of change. The old man can remember travelling into the city by steam train. Also when […]

- Stories of Ourselves

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

‘I never found myself in a book’: Patricia Grace on the importance of Māori literature

In this extract from her new memoir, the New Zealand writer explains why children need to read about people like them

In 1987 I presented a paper at the Fourth Early Childhood Convention in Wellington. I titled the paper “Books Are Dangerous”. Always in my mind were the experiences of teaching reading in the small country schools, and what a difference it made to children’s learning, their self-confidence, their joy, when there were stories about them. Not only about them, but by them. This didn’t mean that they did not like the stories and books about others, because they did, but in writing their own stories and sharing them, they were able to see themselves as worthy protagonists too.

In preparation for the paper, I thought about my own childhood reading. Though I had always liked books, any books, any written-down words or expressions, the ones I read as a child were always exotic. I never found myself in a book.

The children I read about lived in other countries, lands of snow and robins. Sometimes they lived in large houses and had nurses and maids to look after them. They did not belong in extended families, did not speak as I spoke. There were malevolent aunts and terrible stepmothers. It was wrong to be poor. If you were poor you usually did some brave deed that made you rich by the end of the story, when you would marry a princess or a prince. Or you died in the snow while selling matches. Maidens and Jesus were fair. No one was brown or black unless there was something wrong with them or they held a lowly position in society.

I remembered Epaminondas who “didn’t have the sense he was born with”, who carried butter on his head and it melted all over him. He carried sausages in his pocket, which were soon trailing along the ground to be got at by the dogs of the neighbourhood. There was Man Friday who, because he was black, and only because of that – not because he didn’t have excellent survival skills – became Crusoe’s servant. In return for servitude, Crusoe first of all renamed him, then taught him a “proper” language, enlightened him in “proper” manners, social graces and religion. Then there was the original “Uncle Tom” with his servile mentality. There was the story of “The Kind Teddy Bear”.

In many stories blackness was equated with evil: devils, witches’ clothes, unlucky cats, bad wolves. New Zealand history was told from a Eurocentric point of view, if it was told at all.

On the day of the presentation, after telling of my own experiences, I went on to talk about readers and library books in use during my years of teaching in country schools.

The Ready to Read books still very much represented the nuclear Pākehā family and the traditional roles of mothers and fathers. There were some Māori characters but not within a Māori context. I pointed out that in one of the Ready to Read anthologies was the story The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids.

The little white goats, left alone at home, would know the bad wolf by his blackness. There was a large, almost whole-page illustration of this black wolf and his slanting eyes. The wolf dips his paws in flour to make them white and mother-like.

He places his white paws up on the windowsill so that the kids will mistake him for their mother, and therefore will open the door to him. During the trialling of the Ready to Read material in 1983, I wrote to the Department of Education outlining my objections to this particular story. The matter was considered, but in the end publication went ahead.

In every infant class library in my teaching days were the Little Black Sambo books, and the stories of his parents Black Mumbo and Black Jumbo. Though the stories themselves were of interest, the titles of the books and the names the characters were known by were, I thought, demeaning, insulting and enslaving.

The illustrations showed them more like dressed-up golliwogs than the southern Indian characters they were meant to represent. How would it be, I thought to myself, if I wrote a story called Little White Miss, whose parents were White Mummy and White Daddy? What if there was a picture of a white wolf who dipped his paws in coal to make himself acceptable to the black goats? But I only wondered. These ponderings did not become part of my presentation.

At the time I gave the paper, New Zealand history was still being evaluated from a Eurocentric viewpoint. It generally glorified the European settler experience and by doing so negated the Māori experience and settlement of Aotearoa.

A look at some of the vocabulary in use could be taken as a quick example. Take “pioneer” and “settler”. These referred to British pioneers and settlers. The ancestors of the Māori children sitting in our classrooms were referred to in many less complimentary terms. They were savage barbarians, hostile, cunning. Warlike. Yet the British with all their guns and armoury, sweeping in on many indigenous areas of the world, were never referred to as warlike.

In those times, the wars between Māori and Pākehā were still being referred to as “Māori Wars”. A British fighting force was an army. A Māori fighting force was a war party (a term still in use). British fighters were soldiers or colonial forces. Māori fighters were rebels and raiders and warriors (again, still in use). A successful battle by the colonial forces was a victory, by a Māori fighting force a massacre. Reading from my paper:

The books we put before children and the stories we tell them reflect different societies and environments through characters, settings, themes, language, dialogue and dialects. They affirm and set the social and ethical values of the people they are about. They either give identity to the self because they are familiar, or they help us to know others. They show us what is important, or not important to a particular group of people at a particular time. They help explain the world and define relationships with each other, the past, the present, the environments. They enrich and embellish lives.

Every society has its own stories – old stories, but very importantly, new stories too, that give identity to the self and explain that particular world. If there are no books which tell us about ourselves, but tell us only about others, that makes you invisible in the world of literature. That is dangerous.

If there are books and stories about you but they are ones belonging only to the past, it is as though you do not belong in present society. That is dangerous.

If there are books about you but they are negative, demeaning, insensitive and untrue, that is dangerous.

Multiply this by what appears on television, in advertising, teacher attitudes, health services, questionnaires, testing and examinations and in many areas of society, maybe we shouldn’t wonder at the low self-esteem, low self-confidence, and therefore the disengagement of many Māori children with education.

Many in the audience responded angrily. What right did I have to criticise traditional stories that children had read and loved for decades? What proof did I have that certain stories could deliver insidious and negative messages to some young readers? I really stumbled over my replies to these questions, because I didn’t have proof. I hadn’t done research or even discussed these matters with colleagues. It was all gut stuff.

Fortunately for me, I was rescued. The discussion was taken away from me by the audience who took up one side or the other, with much animation, going well past the time when our space was needed for the next session.

This is an edited extract from The Centre: A Writer’s Life by Patricia Grace (Penguin Random House, $NZ40). Grace will be discussing her work at the Auckland Writers Festival on 15 May 2021

- New Zealand

- Asia Pacific

Most viewed

Quality worth making room for

Book of the Week: Second thoughts on Patricia Grace

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

ReadingRoom in association with

Like many people, my love of Māori literature traces back to the short stories of Patricia Grace – specifically a tatty copy of Electric City & Other Stories found in a school library. It was Grace’s sparse, suggestive style that struck me most. Her best short stories leave things unsaid, like there’s a strain of subtext that never quite materialises. The dialogue is often blunt, repetitive, even hypnotic. And the stories are short – many of Grace’s most iconic works span just two or three pages. Her latest collection of short stories, Bird Child & Other Stories , Grace’s first book of fiction for nearly a decade, offers a unique chance to reflect on Grace’s development as a writer, to revisit some foundational work through a new lens.

It feels like there’s been a lot happening for Grace lately. In 2021 she released the excellent, thoughtful memoir From the Centre: A Writer’s Life ; that same year, a film adaptation of Cousins finally saw release (which at one point seemed like it’d never get off the ground). Likewise, in the broader zeitgeist of modern Māori literature – the emergence of vibrant contemporary writers, and a renewed interest in ‘the classics’ – she continues to occupy the mantle of our most important writer (rivalled only by Witi Ihimaera).

However, while Bird Child & Other Stories is being promoted as a ‘new collection’, the truth is a little more complex (and I imagine less marketable). There are new stories here, but a significant chunk of this collection is reworked older material – some obscure, some not. That’s not a criticism; Bird Child continues what was started in From the Centre ’s best moments, which were almost entirely concerned with Grace’s writing process and how her seminal stories came to be.

The book is divided into three sections. The first contains contemporary takes on traditional pūrākau. The second focuses on the character of Mereana, a young girl living in Wellington during the war. The third is a less-focused mix of new stories (minus “The Machine”, a rework of one of Grace’s oldest stories).

It opens with a title story that borders on novella-length. “Bird Child” is an ambitious piece of historical magical-realism, spanning multiple perspectives and narratives. The story’s main narrative opens with the birth of the ‘child’, who must be immediately killed so that their crying will not alert pursuers. The remains are inserted into the hollow of a tree, and the wairua becomes entangled with a bird. In its structural scope, the story feels like a microcosm of Grace’s past experiments in the form: varied narrative voices, fantastical perspectives on an otherwise grounded setting, play-like sections that develop simply through dialogue. The way in which the titular Bird Child exists on a plane between life and death recalls Missy’s first section in Cousins , narrated by her dead brother. Likewise, Grace demonstrates her deft ‘maturing’ of narrative voice – the voice of a child that develops before the reader (a trick famously used in her 1986 novel Potiki ).

The heart of the story is, however, the character of Puawhaanganga: a respected warrior who must atone for his failure to protect the village. An overlooked aspect of Grace’s fiction is her fascination with – and respect for – characters who are uncannily committed to their practice. One of the reasons I believe The Kuia and the Spider to be a great work of children’s literature is that Grace has the gall to – in a medium obsessed with ‘fixing’ deviance – allow the story’s rivals the joy of stoking their all-consuming competition for the rest of their days.