AML Compliance for Travel Agencies

Schuyler "Rocky" Reidel

Schuyler is the founder and managing attorney for Reidel Law Firm.

- Published On: July 15, 2023

- Updated On: July 15, 2023

- Other Trade Articles

In today’s globalized economy, money laundering and terrorist financing have become significant threats that can have severe repercussions for industries all over the world. The travel industry, with its vast network of transactions and international connections, is particularly vulnerable to these illicit activities. To combat this ever-present risk, travel agencies must prioritize Anti-Money Laundering (AML) compliance within their operations.

Understanding AML (Anti-Money Laundering) Regulations in the Travel Industry

AML regulations are designed to detect and prevent the illegal movement of funds through various financial systems. In the travel industry, these regulations aim to mitigate the risks associated with money laundering, such as disguising the proceeds of criminal activities as legitimate travel expenses.

To effectively implement AML compliance measures, it is crucial to have a deep understanding of the regulations specifically designed for the travel industry. These regulations outline the responsibilities of travel agencies and establish guidelines on customer due diligence, risk assessments, monitoring, reporting, and more.

Why AML Compliance is Essential for Travel Agencies

Ensuring AML compliance is not only a legal obligation for travel agencies but also a critical component in safeguarding their reputation and maintaining the integrity of the global financial system. Failure to comply with AML regulations can result in severe penalties, including hefty fines, legal consequences, and even the suspension or revocation of a agency’s operating license.

Key Steps to Achieve AML Compliance in Travel Agencies

Implementing a robust AML compliance program requires a systematic approach. Travel agencies must establish comprehensive policies and procedures that encompass various elements, including customer due diligence, risk assessments, internal controls, training and education programs, and effective monitoring and reporting systems.

1. Customer Due Diligence: Travel agencies should conduct thorough customer due diligence by verifying the identity of their customers, assessing their risk profile, and monitoring transaction activities to ensure they align with expected patterns.

2. Risk Assessments: Regularly conducting risk assessments is vital to identify and prioritize potential areas of vulnerability within an agency’s operations. By understanding these risks, travel agencies can implement adequate controls and monitoring systems.

3. Internal Controls: Developing internal controls, such as implementing segregation of duties and establishing reporting mechanisms, helps ensure compliance with AML regulations. These controls should be regularly reviewed and updated to address emerging risks.

4. Training and Education: Providing comprehensive training and education programs to employees is essential to create awareness about AML regulations and the importance of compliance. Ongoing education helps employees stay updated on evolving money laundering techniques and regulatory changes.

5. Monitoring and Reporting Systems: Establishing robust systems for monitoring and reporting suspicious transactions is crucial for detecting and deterring money laundering activities. Travel agencies should have mechanisms in place to quickly and effectively report suspicious transactions to the relevant authorities.

The Impact of AML Non-Compliance on Travel Agencies

The consequences of non-compliance with AML regulations can be devastating for travel agencies. Apart from the financial and legal penalties mentioned earlier, non-compliant agencies may face reputational damage, loss of customer trust, difficulties in obtaining financial services, and strained relationships with key business partners and suppliers.

A Comprehensive Guide to Implementing AML Policies and Procedures in Travel Agencies

Implementing effective AML policies and procedures in travel agencies requires careful planning and execution. Here is a step-by-step guide to help travel agencies navigate this process:

1. Conduct a thorough risk assessment to identify potential vulnerabilities within your agency’s operations. This assessment should take into account factors such as transaction volumes, customer profiles, locations served, and the complexity of services offered.

2. Develop comprehensive AML policies and procedures that align with the specific requirements of your agency and the regulations governing the travel industry. These policies should cover all aspects of AML compliance, including customer due diligence, transaction monitoring, record-keeping, and reporting procedures.

3. Establish a dedicated team or designate a responsible individual to oversee the implementation and ongoing management of the AML compliance program. This includes training employees, ensuring policies are followed, and conducting regular audits to assess the effectiveness of controls and procedures.

4. Invest in technology solutions that facilitate AML compliance. Many software tools are available that can help automate transaction monitoring, customer due diligence, and reporting processes, making it easier for travel agencies to detect and report suspicious activities.

5. Monitor and update your AML policies and procedures regularly to keep pace with the evolving nature of money laundering techniques and regulatory changes. Stay informed about industry best practices and regulatory updates to ensure your agency remains compliant.

Best Practices for Conducting Customer Due Diligence in the Travel Industry

Customer due diligence (CDD) is a vital component of AML compliance in the travel industry. It involves collecting and verifying customer information to establish their identity and assess their risk profile. Implementing the following best practices helps travel agencies strengthen their CDD processes:

1. Obtain and verify customer identities using reliable and independent sources, such as government-issued identification documents, passports, or driver’s licenses. Consider using identity verification services for enhanced accuracy and efficiency.

2. Perform risk assessments based on factors such as the purpose and nature of the customer’s travel, the amount of money involved, and the countries involved. Higher-risk customers should undergo enhanced due diligence procedures.

3. Conduct ongoing monitoring of customer transactions to identify any unusual or suspicious patterns. Implement systems that flag transactions that deviate from expected behaviors or exceed predetermined thresholds.

4. Train employees on the importance of vigilant customer due diligence and provide them with the necessary knowledge and tools to identify potential red flags. Establish guidelines for reporting suspicions to the designated compliance officer or department.

How to Conduct Effective Risk Assessments for AML Compliance in Travel Agencies

Risk assessments play a crucial role in achieving effective AML compliance. To conduct accurate risk assessments, travel agencies should follow these steps:

1. Identify potential risks by reviewing industry-specific AML guidelines, legal requirements, and industry trends. Consider both internal and external factors that may pose risks to your agency, such as the geographic scope of your operations and the customer base you serve.

2. Assess the likelihood and impact of each identified risk. Assign scores or ratings based on the severity and probability of occurrence. This helps prioritize risks and allocate resources accordingly.

3. Develop appropriate controls and mitigation strategies for each identified risk. These controls can include enhanced customer due diligence procedures for high-risk customers, transaction monitoring systems, and regular employee training.

4. Regularly review and update risk assessments to ensure they remain relevant and reflect any changes in your agency’s operations or the risk landscape. Ongoing monitoring and reassessment will help identify emerging risks and adapt your controls and procedures accordingly.

The Role of Training and Education in Ensuring AML Compliance for Travel Agencies

Training and education play a pivotal role in promoting AML compliance within travel agencies. Comprehensive training programs enable employees to understand the significance of AML regulations and equip them with the knowledge and skills necessary to identify and prevent potential money laundering activities. Key considerations for effective training include:

1. Provide general AML training to all employees, regardless of their roles or responsibilities within the agency. Everyone should have a basic understanding of AML regulations and their individual responsibilities in ensuring compliance.

2. Tailor training programs to address the specific risks and requirements relevant to the travel industry. Incorporate real-life scenarios and case studies to help employees grasp the practical implications of AML compliance.

3. Conduct regular refresher training to keep employees updated on new money laundering techniques, regulatory changes, and best practices. This ensures continued compliance and helps maintain a culture of vigilance against money laundering activities.

4. Engage senior management actively in training and education programs and ensure they communicate their commitment to AML compliance throughout the organization. Strong leadership fosters a culture of compliance and reinforces the importance of AML measures.

Effective Monitoring and Reporting Systems for AML Compliance in Travel Agencies

Implementing effective monitoring and reporting systems is crucial for detecting and reporting suspicious transactions in a timely manner. Consider the following best practices when establishing robust monitoring and reporting systems:

1. Implement automated transaction monitoring tools designed specifically for the travel industry. These tools can help identify patterns and behaviors indicative of money laundering activities, enabling agencies to take appropriate action promptly.

2. Establish clear procedures for reporting suspicious transactions internally and to the relevant authorities. Designate a compliance officer or department responsible for receiving and investigating suspicious activity reports and ensuring their timely submission to the appropriate authorities.

3. Develop a culture of vigilance among employees, encouraging them to report any suspicions promptly and without fear of reprisal. Create anonymous reporting mechanisms to facilitate the reporting of concerns and foster open communication.

4. Regularly review and analyze transaction monitoring alerts and suspicious activity reports to identify any potential vulnerabilities or areas for improvement. This ongoing review helps refine monitoring systems and enhances overall compliance.

Utilizing Technology Solutions to Enhance AML Compliance in the Travel Industry

Technology solutions can significantly enhance AML compliance efforts in the travel industry by automating repetitive processes, improving accuracy, and enabling real-time monitoring. Consider the following technological solutions to strengthen AML compliance:

1. Automated Customer Due Diligence (CDD) Systems: These systems streamline customer onboarding and verification processes by automatically collecting and verifying customer identity information from reliable sources. Such systems reduce manual effort and enhance accuracy.

2. Transaction Monitoring Software: Implementing transaction monitoring software helps identify suspicious patterns or behaviors in real-time. These systems employ advanced algorithms to analyze vast amounts of transaction data, giving travel agencies a more comprehensive view of their operations.

3. Data Analysis and Artificial Intelligence (AI) Solutions: Utilize AI and data analysis tools to detect and investigate potential money laundering activities. These tools can identify complex transaction patterns and relationships that may go unnoticed with manual processes alone.

4. Blockchain Technology: Explore the adoption of blockchain technology to increase transparency and minimize the risk of fraudulent transactions. By utilizing decentralized and immutable ledgers, travel agencies can strengthen their AML compliance efforts and minimize the potential for money laundering.

Common Challenges Faced by Travel Agencies in Achieving AML Compliance and How to Overcome Them

Despite the importance of AML compliance, many travel agencies face challenges when attempting to achieve and maintain compliance. The following are some common challenges and recommendations for overcoming them:

1. Limited Resources: Some agencies may lack the necessary financial and human resources to fully implement robust AML compliance programs. Seek guidance from industry associations and regulatory bodies, leverage technology solutions to streamline processes, and consider outsourcing certain AML functions to specialized service providers.

2. Evolving Regulations: AML regulations are constantly evolving, making it challenging for travel agencies to stay up-to-date and ensure compliance. Establish a dedicated compliance function within the agency to monitor regulatory updates regularly and conduct periodic reviews and updates of policies and procedures.

3. Complex Customer Profiles and Transactions: The travel industry caters to a diverse range of customers with varying risk profiles. Balancing the need to provide excellent customer service while implementing robust due diligence procedures can be challenging. Establish clear guidelines for customer due diligence and leverage technology solutions to streamline and automate processes where possible.

4. Lack of Awareness and Training: Employees may not fully understand the importance of AML compliance or have the necessary knowledge to identify potential money laundering activities. Invest in comprehensive training programs, communicate the significance of AML measures, and regularly reinforce employee understanding through ongoing education.

Case Studies: Successful Implementation of AML Compliance Programs by Leading Travel Agencies

Examining real-life case studies of travel agencies that have successfully implemented AML compliance programs can provide valuable insights. Analyzing these success stories can help identify best practices and strategies that other agencies can adopt. Some well-known travel agencies have taken proactive steps to ensure compliance, demonstrating the importance of AML compliance as a competitive advantage in the industry.

Regulatory Updates and Trends Impacting AML Compliance for Travel Agencies

AML regulations are continually evolving to address emerging threats and adapt to the rapidly changing global landscape. It is essential for travel agencies to stay informed about regulatory updates and industry trends that may impact their AML compliance efforts. Monitor relevant regulatory bodies, attend industry conferences and seminars, and leverage industry publications and resources to stay up-to-date with the latest developments.

The Benefits of Maintaining Strong Partnerships with Financial Institutions to Ensure AML Compliance in the Travel Industry

Collaboration with financial institutions can significantly enhance AML compliance efforts within the travel industry. Establishing strong partnerships with banks and other financial institutions can provide numerous benefits, such as:

1. Access to AML Expertise: Financial institutions are well-versed in AML compliance requirements and have dedicated teams to ensure compliance. Leveraging their expertise can help travel agencies navigate complex AML regulations and establish industry best practices.

2. Enhanced Information Sharing: Establishing partnerships with financial institutions facilitates the exchange of valuable information related to emerging money laundering threats and trends. Such collaborations can help travel agencies stay ahead of potential risks and strengthen their compliance programs.

3. Improved Due Diligence Processes: Collaboration with financial institutions can streamline the customer due diligence process. Sharing information and leveraging the expertise of financial institutions can expedite verification processes and enhance the overall effectiveness of AML compliance.

4. Increased Industry Credibility: By actively maintaining partnerships with reputable financial institutions, travel agencies demonstrate their commitment to AML compliance and boost their credibility within the industry. Such collaborations can contribute to building trust among customers, business partners, and regulators.

In Conclusion

AML compliance is an essential responsibility for travel agencies operating in today’s global environment. By understanding the regulatory framework, implementing robust policies and procedures, conducting diligent risk assessments, providing comprehensive training, and leveraging technology solutions, travel agencies can effectively combat money laundering activities. Maintaining a culture of compliance and forging strong partnerships with financial institutions further strengthens AML efforts, ensuring the integrity and security of the travel industry while upholding global standards of financial transparency.

Share this:

Do I Need My FDD Reviewed?

If you’re on the brink of signing a franchise agreement, you might be asking: do I need my FDD reviewed? The answer is unequivocally yes.

The Importance of the Cross-Default Clause in a Franchise Agreement

If you’re involved in a franchise agreement, understanding the cross default clause is pivotal. This clause dictates what happens if a party falls short in

Can a Franchisee Terminate a Franchise Agreement?

Can a franchisee terminate a franchise agreement? The answer is yes, under certain circumstances. This pivotal decision, governed by the original contract and state laws,

Check Out Our Latest Videos:

Galveston, texas, +1(832)510-3292, © reidel law firm 2023.

The FinCEN Travel Rule

- February 25, 2021

- AML Compliance , Banks , Blog , Casino and Gaming , FinTechs , MSBs

Disclaimer: The contents of this article are intended to provide a general understanding of the subject matter. However, this article is not intended to provide legal or other professional advice, and should not be relied on as such.

The FinCEN “Travel Rule” has many requirements and nuances that can challenge and confuse new and seasoned AML compliance professionals alike. From the basics of what types of transactions fall under the Rule, to mandatory versus optional data requirements, to its many exemptions – as well as the nuances addressed by subsequent FinCEN guidance not contained in the Rule itself – compliance professionals need to understand the details of this longstanding Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) regulation.

This article begins with a review of the fundamentals of the FinCEN Travel Rule , and why compliance is so important to anti-money laundering efforts. Learn about the nuances of complying with the Travel Rule, including a discussion of pending changes to the Travel Rule in an October 2020 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking; Fedwire versus Travel Rule requirements; aggregated funds transfers; Originator name issues; and transfers by non-customers.

What is the FinCEN Travel Rule?

In January 1995, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve and FinCEN jointly issued a Rule for banks and other nonbank financial institutions, relating to information required to be included in funds transfers. The Rule is comprised of two parts – the Recordkeeping Rule, and what’s come to be known as the Travel Rule. The Travel Rule was promoted by FinCEN, in keeping with their mandate to enforce the Bank Secrecy Act .

The Recordkeeping Rule and the Travel Rule are complementary. The Recordkeeping Rule requires financial institutions to collect and retain the information that in turn, per the Travel Rule, must be included with a funds transfer and passed along – or “travel” – to each successive bank in the funds transfer chain. The Recordkeeping Rule does however serve other purposes besides ensuring that information is available to include with funds transfers.

The terms “transfer” and “transmittal” are used throughout this regulation. The distinction between these two terms is simple: a bank performs transfers, and a non-bank financial institution performs transmittals. The term “transfer” will primarily be used from this point on to refer to both types of transactions.

The Underlying Objective

Fund transfers have been the tool of choice for money laundering, fraud, and much more, for decades. As FinCEN’s mission is to implement, administer, and enforce compliance with the Bank Secrecy Act, it has the authority to require financial institutions to keep records that, according to FinCEN, have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory investigations or proceedings, or even in intelligence or counterintelligence matters when terrorism is involved.

Ultimately, the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule is primarily designed to help law enforcement to detect, investigate and prosecute money laundering and financial crimes, by preserving the information trail about who’s sending and receiving money through funds transfer systems. In other words, it helps them follow the money.

Transactions Subject to the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule

The Recordkeeping and Travel Rule states that it applies to funds transfers. The definition of a funds transfer is very important, as highlighted later in the discussion of the most recent Notice of Proposed Rulemaking.

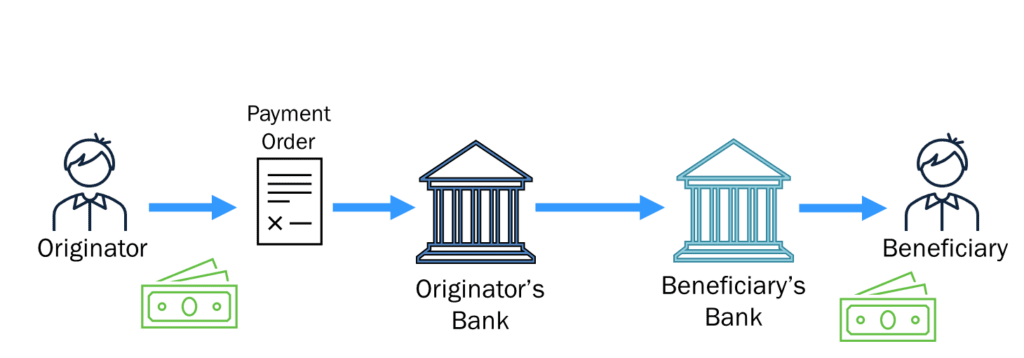

The Rule defines a funds transfer as a series of transactions, beginning with the Originator’s payment order, made for the purpose of making a payment of money to the Beneficiary of that payment order.

Below is a basic illustration of a funds transfer. An Originator creates a Payment Order to pay money to a specific Beneficiary. The Originator delivers the Payment Order to his bank, which then passes on the Payment Order details to the bank holding the Beneficiary’s account. The funds transfer is complete when the Beneficiary’s Bank accepts the Payment Order on behalf of the Beneficiary.

In today’s world, funds transfers are electronic, and a wire transfer is the most common form of electronic funds transfer. At its essence, a wire transfer is simply a message from one bank to another, passed through an electronic system, such as Fedwire, SWIFT , or CHIPS.

Electronic Funds Transfers That are Excluded

Besides wire transfers, there are many types of electronic funds transfers, or EFTs in use today. Although all are in essence funds transfers, these types of transactions are specifically excluded from the definition of a funds transfer or transmittal in the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule. Instead, these types of electronic funds transfers are defined in, and governed by, the Electronic Funds Transfer Act, otherwise known as Regulation E. [i] Currently, these are:

- ACH (automated clearing house) transactions

- ATM (automated teller machine) transactions

- Point of Sale (POS) transactions

- Direct deposits or withdrawals

- Telephone banking transfers

Terminology Review

The terminology used in the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule is in many cases unique. The more commonly-used terms when referring to wire transfers and other electronic funds transfers come from the Uniform Commercial Code’s Article 4A, which governs funds transfers. [ii]

Throughout this article, UCC 4A terminology will be used as it is more commonly understood:

* The spelling shown here is per the regulation; it is not the correct spelling of this word according to widely-accepted sources.

The term Sender per UCC 4A refers to the person who is delivering the Payment Order to the Receiving Bank. This person would typically be the Originator, but could potentially be a third party, as discussed further below.

Funds Transfer Data Requirements

The Rule divides the data requirements on a funds transfer into two groups: (1) data that is mandatory, and (2) data that, if the originator provides it , must be included.

First, the data that must be included on the funds transfer by the Originator’s Bank is:

- The Originator’s name

- The Originator’s address

- The Originator’s account number (if there is one)

- The identity of the Beneficiary’s Bank

- The payment amount

- The payment execution date

Typically, a bank will automatically populate the Originator’s name and address information on a wire transfer directly from the customer record. This is because it is very important that the Originator’s name reflects the actual party initiating the Payment Order. (This topic is explored further in the Deep Dives section below.)

The second group of data elements is optional – meaning, if the Originator provides any of this information, it must be included on the funds transfer record. This information includes:

- The Recipient’s (or Beneficiary’s) name

- The Beneficiary’s address

- The Beneficiary’s account number or other identifiers

- Any other message or payment instructions – what typically are entered in the freeform text fields on a wire transfer, such as the Originator to Beneficiary Information or OBI field on a Fedwire.

Even though this information is not mandatory per FinCEN’s Travel Rule requirements, nothing precludes a bank from mandating customers to supply it. From an operational perspective, at least the Beneficiary’s account number should be required information to minimize the risk that the transfer will be rejected and returned by the Receiving Bank as unpostable.

As well as being highly valuable to law enforcement, Beneficiary information is critical to a bank’s fraud detection , suspicious activity monitoring and sanctions compliance efforts. Without this information, detecting an unusual or suspicious wire transfer recipient, establishing a pattern of transaction activity to a particular recipient, or identifying a customer transaction with an OFAC-sanctioned party is impossible.

Exemptions from the Travel Rule

In addition to the types of EFTs that are not subject to the Rule (as they fall under the jurisdiction of Regulation E) there are several categories, or classes, of funds transfers that are exempt from FinCEN’s Travel Rule’s requirements. Specifically:

- A funds transfer that is less than $3,000.

- A funds transfer where the sender and the recipient are the same person . For example, if an individual is wiring money from her account at Bank A to her account at Bank B, Bank A does not have to obtain and retain the Travel Rule mandatory information for this transfer.

- A funds transfer made between two account holders at the same institution. Commonly known as a book transfer, this transaction is not processed through the Federal Reserve, but is simply a journal entry on the financial institution’s books.

- A bank, or a U.S. subsidiary thereof

- A commodities/futures broker, or a U.S. subsidiary thereof

- The U.S. government; a state or local government

- A securities broker/dealer, or a U.S. subsidiary thereof

- A mutual fund

- A federal, state or local government agency or instrumentality

Nothing prevents a financial institution from ignoring these exemptions; the institution is free to follow the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule requirements with every funds transfer. Such a practice benefits all the financial institutions involved in the transaction, as well as law enforcement.

Recordkeeping and Travel Rule Enforcement

FinCEN enforcement actions over the years have never solely targeted violations of the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule. This is likely because as a matter of operational efficiency, financial institutions typically populate the basic mandatory information on all outgoing funds transfers and maintain records of such.

However, it is important not to overlook the other key element of the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule: records retrievability.

A financial institution may be approached by federal, state, or local law enforcement, its regulator, another regulatory agency, or by subpoena, to provide specific funds transfer records.

If the institution is the Originator’s Bank, the mandatory funds transfer information to be collected and retained (Originator name & address, etc.) must be retrievable upon request, based on the Originator’s name . If the Originator is the institution’s established customer, transaction retrieval by the Originator’s account number may also be requested. A Beneficiary’s Bank must be able to retrieve funds transfer records by the Beneficiary’s name, and if an established customer, also by account number.

The FinCEN Travel Rule requires all funds transfer records to be retained for a minimum of five years from the date of the transaction.

Once funds transfer records are requested, the Rule states they must be supplied within a reasonable period – which may likely be negotiated between the financial institution and the requestor.

The 120-Hour Rule

However, financial institutions should be aware of a lesser-known clause within Section 314 of the USA PATRIOT Act that could impact records retrieval. Commonly known as the 120 Hour Rule , it states that any information, on any account that is opened, maintained, or managed in the U.S. requested by a federal banking agency, must be provided by the financial institution within 120 hours (5 days) after receiving the request. Funds transfer records would likely fall within the scope of this Rule.

Anecdotally, regulators have not imposed the 120 Hour Rule often. Financial institutions should nevertheless be prepared to respond to regulatory or law enforcement requests as quickly and efficiently as possible. IRS and civil case subpoenas requesting funds transfer records also typically have a short response window.

Recordkeeping and Travel Rule Guidance: A Deep Dive

The following sections explore deeper topics relating to Recordkeeping and Travel Rule guidance, including:

- The October 2020 Joint Notice of Proposed Rulemaking impacting the Rule

- Fedwire versus the Travel Rule

- Originator name issues

- Aggregated funds transfers

- Funds transfers for non-customers

Joint Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

On October 23, 2020, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve and FinCEN issued a Joint Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) to amend the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule regulations. Written comments on the Proposed Rule were due by the end of November 2020. The next step is a publication of the Final Rule, but FinCEN has not set a date for this.

According to the website Regulations.gov , 2,882 comments were submitted for the NPRM. Commenters ranged from major banking groups such as the American Bankers Association to private individuals. The comments were overwhelmingly negative.

The NPRM proposes two major changes, discussed below.

Reducing the Minimum Dollar Threshold for Recordkeeping and Travel Rule Compliance on Cross-Border Funds Transfers

Part 1 of the NPRM proposes reducing the $3,000 threshold for Recordkeeping and Travel Rule compliance to $250 for cross-border transactions. The threshold for domestic transactions would remain at $3,000.

While this change may not have a major impact on financial institutions that ignore the dollar threshold exemption, it would significantly impact those institutions that follow it. There are some interesting nuances in this proposed change regarding what is meant by “cross border.”

Initially, a “cross-border” transaction is defined as one that, “begins or ends outside of the United States.” The United States includes the 50 states, the District of Columbia, the Indian lands (as that term is defined in the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act), and the Territories and Insular Possessions of the United States. [iii]

A funds transfer would be considered to “begin or end outside the United States” if the financial institution knows, or has reason to know, that the Originator, the Originator’s financial institution, the Recipient/Beneficiary, or the Recipient/Beneficiary’s financial institution is located in, is ordinarily resident in, or is organized under the laws of a jurisdiction other than the United States. Furthermore, a financial institution would have “reason to know” that a transaction begins or ends outside the United States only to the extent such information could be determined based on the information it receives in the payment order or otherwise collects from the Originator.

The driving factor behind this regulatory change is the benefit to law enforcement and national security. FinCEN’s analysis of SAR filings , as well as comments collected by the Department of Justice from agents and prosecutors at the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, the Internal Revenue Service, the U.S. Secret Service, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, all supported lowering (or eliminating altogether) the reporting threshold, in order to disrupt illegal activity and increase its cost to the perpetrators.

According to FinCEN and these other law enforcement agencies, cross-border funds transfers, and especially lower dollar transfers in the $200 to $600 dollar range, are being used extensively in terrorist financing and narcotics trafficking to avoid reporting and detection.

For those institutions that abide by the minimum reporting threshold, the new lower cross-border threshold presents operational and programmatic challenges. The distinction between a cross-border and a domestic transaction is not always clear. For example, if a financial institution has no direct foreign correspondent banking relationships, its cross-border funds transfers must flow through a U.S. intermediary institution, and therefore the Federal Reserve. Automated systems may interpret such transactions as domestic because the first receiving institution will always be U.S.-based.

Recordkeeping and Travel Rule Applies to Virtual Currency

The second element of the NPRM would make funds transfers involving convertible virtual currency (CVC) and other digital assets, to be subject to the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule. CVC, more commonly known as cryptocurrency or cyber-currency, is a medium of exchange with an equivalent value in currency or acts as a substitute for currency, but at present does not fall under the regulatory definition of “money” (also known as legal tender).

The Proposed Rule now defines CVC as money. This is significant because transfers of CVC now legally fall within the meaning of “a transfer of money” to which the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule applies.

The “why” behind this aspect of the Proposed Rule is the exponential growth in CVC use for money laundering, terrorist financing, organized crime, weapons proliferation, and sanctions evasion. CVC’s anonymity makes it particularly attractive for financial crime. Bad actors can convert illegal proceeds into virtual currency and then transmit it to any destination anonymously within seconds, where it is redeemed for cash again or converted to another form. This makes CVC a perfect mechanism for the layering phase of money laundering.

For more information, check out our blog on the crypto travel rule .

NPRM Background and the “FATF Travel Rule”

Events leading up to the NPRM provide an interesting background, especially as they are intertwined with global anti-money laundering efforts – specifically those of the Financial Actions Task Force (FATF) and what has come to be known as the “FATF Travel Rule.”

As virtual currency’s popularity began to grow exponentially, regulators in the United States and globally were caught off-guard. It was not well understood, and there were no real protocols in place to govern it. In March 2013 , FinCEN released initial guidance clarifying that virtual currency exchangers and administrators must register as money service businesses, pursuant to federal law. [iv]

In October 2018 , FATF published guidance that clearly defined just what are virtual assets and virtual asset service providers (VASPs). [v] FATF followed this up in February 2019 with a far-reaching Interpretive Note to Recommendation 15 (New Technologies), in a Public Statement titled “Mitigating Risks from Virtual Assets.” [vi]

This publication included two key proposals that generated backlash from the cryptocurrency sector:

For one, it proposed that VASPs should, at a minimum, be required to be licensed or registered in the jurisdiction(s) where they are created. As well, VASPs should be subject to effective systems for monitoring compliance with a country’s AML/CFT requirements, and be supervised by a competent authority – not a self-regulatory body.

Second, it introduced what’s come to be known as the FATF Travel Rule for funds transferred over $1,000 – specifically referencing virtual asset transfers. These requirements match up point-for-point with the United States Recordkeeping and Travel Rule in terms of required funds transfer data to be obtained, retained and passed on.

In May 2019 , FinCEN published lengthy and complex guidance [vii] effectively stating that CVC-based transfers processed by nonbank financial institutions that meet the definition of a money service business are subject to the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA), and thereby the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule. Furthermore, it clarified that a transfer of virtual currency involves a sender making a “transmittal order.”

One month later in June 2019 , the FATF formally adopted the proposals from their 2018 guidance by incorporating them into the FATF 40 Recommendations – specifically, Recommendation 16, Wire Transfers.

In October 2020, the Federal Reserve Board and FinCEN issued their Joint NPRM, which would codify their May 2019 guidance as well.

Fedwire vs. the FinCEN Travel Rule

With respect to the implementation and enforcement of the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule, there is an interesting disconnect between the two key divisions of the U.S. Treasury Department. FinCEN is tasked with administering and enforcing the BSA, of which the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule is a part. The Federal Reserve Banks, also part of the US Treasury Department, own and operate Fedwire , the country’s primary funds transfer service. Yet the Fedwire system does no validation whatsoever that funds transfers processed through it include the basic, mandatory information required by the Travel Rule. The only data elements required to process a Fedwire transfer are the sending and receiving banks’ Fed routing numbers, the transaction amount, and its effective date. [viii]

One might conclude that law enforcement could have much more information on funds transfers at its disposal if the federal government’s actual funds transfer system made that information required. Today, should an Originator’s Bank fail to include the Travel Rule’s mandatory information (Originator’s name and address, etc.) on a funds transfer, the Receiving Bank is under no obligation to return the transfer and request the mandatory information. Instead, the burden is solely on the Originator’s Bank to comply, and any subsequent Receiving Banks’ responsibility is simply to retain (and pass on, if necessary) the information received.

Aggregated Funds Transfers

A financial institution may aggregate, or combine, multiple individual funds transfer requests into a single, aggregated funds transfer/transmittal.

For purposes of the FinCEN Travel Rule, whenever a financial institution aggregates multiple parties’ transfer requests into one single transfer, the institution itself becomes the Originator. Similarly, if there are multiple Beneficiaries in this aggregated transfer, but all with accounts at the same Receiving institution, then that institution becomes the Beneficiary on the aggregated funds transfer.

Aggregated funds transfers are common with money service businesses , as illustrated here:

A money service business (MSB) in Texas has several transmittal orders from various individuals, who are all sending funds to recipients via one particular Mexican casa de cambio. The Texas MSB aggregates these transactions into a single transmittal order, submitted to the MSB’s bank in Texas, for which the Beneficiary is the Mexican casa de cambio. This transmittal order does not identify the individual Originators or Beneficiaries of the underlying transfers. The Texas bank passes on the aggregated transmittal order to the Mexican bank holding the account of the casa de cambio. Once this funds transfer is complete, the casa de cambio pays the Mexican recipients, based on separate individual transmittal orders it received directly from the Texas MSB.

In this aggregated funds transfer scenario, the Originators’ payments are completed through a combination of individual transmittal orders between the senders and recipients, and an aggregated funds transfer between the MSB and the casa de cambio.

To summarize, the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule requirements for the Texas MSB and its Texas bank are as follows.

The MSB must keep a record of each customer’s individual transmittal order. The MSB is the Originator’s Bank, and the individual sender is the Originator. The Beneficiary is the individual who will receive the money, and the Beneficiary’s Bank is the Mexican casa de cambio.

The Texas bank must retain and pass on the information on the aggregated funds transfer between the MSB and the casa de cambio. On this funds transfer record, the Originator is the Texas MSB, the Texas bank is the Originator’s Bank, the Mexican casa de cambio is the Beneficiary, and its bank is the Beneficiary’s Bank.

Originator Name Issues

The Originator’s full true name is a required data element per the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule. A financial institution will typically populate the Originator’s name and address information on a funds transfer directly from its customer record.

A financial institution may be faced with a situation where a customer does not want his/her/their actual name to be present on a funds transfer.

For example, a customer may ask the financial institution to replace the Originator name on a funds transfer with that of some other party. Oftentimes, the customer is sending funds from their own account on behalf of someone else. Individuals as well as business entities may make such a request, for a variety of underlying reasons.

Changing an Originator’s name from that of the account holder to that of a third party is clearly a violation of the spirit of the Travel Rule, although not specifically addressed within it. Further, it exposes the financial institution to risks of abetting fraud, tax evasion, and other illicit activities.

The FinCEN Travel Rule does, however, specifically prohibit the use of a code name or pseudonym in place of an individual Originator’s true name. However, there are some exceptions to this with respect to commercial/business customers. For instance, a business may have several accounts, each of which is titled in a manner that reflects the purpose of the account – such as “Acme Corporation Payroll Fund.” Use of an account name that reflects its commercial purpose is acceptable for an Originator name under the Travel Rule.

Other acceptable Originator names for business customers are names of unincorporated divisions or departments, trade names, and Doing Business As (DBA) names, such as these examples:

- “Giant Inc Engineering Division”

- “McDonald’s” (a trade name for the McDonald’s Corporation)

- “Sue’s Flowers” (the DBA name for a sole proprietorship owned by Sue Smith)

Joint Accounts

When a funds transfer is made from a joint account, technically both account holders are the Originators. However, automated funds transfer systems, including Fedwire, do not provide space for more than one Originator name and address. FinCEN provides financial institutions with a solution: [ix] simply identify the Originator on the transfer as the joint account holder who requested it.

Funds Transfers for Non-Customers

Additional rules apply when a financial institution accepts a funds transfer order from a party that is not an established customer (i.e., a non-customer).

If the payment order is made in person by the Originator, the financial institution must verify his/her identity, and obtain and retain the following information:

- Originator’s name and address

- Type of identification document reviewed, and its number and other details (e.g., driver’s license number, state where issued)

- The Originator’s tax ID number, or, if none, an alien identification number or passport number and country of issuance. Should the Originator state that he/she has no tax ID number, a record of this fact should also be retained.

If the person delivering the payment order is not the Originator, the financial institution should record that person’s name, address, and tax ID number (or alternative as described above), or note the lack thereof. The institution should also request the actual Originator’s tax ID number (or alternative as described above) or a notation of the lack thereof. The institution must also keep a record of the method of payment for the funds transfer (such as a check or credit card transaction).

- The Recordkeeping and Travel Rule is a joint regulation under the Bank Secrecy Act, issued by the Federal Reserve Board and FinCEN.

- Record retrieval is equally important as record creation. Financial institutions should ensure full records of all outgoing and incoming funds transfers are retained for five years and can be retrieved by Originator name or account number (for established customers).

- Exemptions to the Rule, such as funds transfers under $3,000, are not mandatory . Financial institutions may choose to fully comply with the Recordkeeping and Travel Rule for every funds transfer sent or received, no matter the dollar amount or the parties involved.

- If the Originator is not required to provide the Beneficiary’s name, address, and account number on every wire transfer, this will have a significant detrimental impact on the financial institution’s suspicious activity monitoring, fraud detection, and sanctions compliance efforts.

- The October 2020 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking impacts cross-border funds transfers and the virtual currency industry. No date has yet been set for the publication of a Final Rule.

- A customer should not be allowed to substitute another name for the Originator on an outgoing funds transfer, as this exposes the financial institution to the risk of acting as a conduit for fraud, tax evasion, and other illicit activity, no matter how innocent or legitimate the customer’s request may seem.

- A financial institution that sends or receives aggregated funds transfers, or transfers for non-customers, should examine its existing processes to ensure compliance with the special rules for these activities.

How Alessa Can Help

Alessa is an integrated AML compliance software solution for due diligence, sanctions screening , real-time transaction monitoring , regulatory reporting and more. The solution integrates with existing core systems and includes:

- Identity verification and customer due diligence for KYC/KYB

- Real-time transaction monitoring and screening

- Sanctions, PEPs, watch list, crypto and other forms of screening

- Configurable risk scoring

- Automated regulatory reporting

- Advanced analytics like anomaly detection and machine learning

- Dashboards, workflows and case management

With Alessa, customers can monitor their wire transactions and ensure that the appropriate process is in place to collect and record the right information in order to comply with regulatory bodies. Contact us today to see how we can help you implement or enhance the AML program at your financial institution to comply with mandates such as the FinCEN Travel Rule.

[i] 15 USC 1693 et seq.

[ii] The Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) is a comprehensive set of laws governing all commercial transactions in the United States. It is not a federal law, but a uniformly adopted state law. Uniformity of law is essential in this area for the interstate transaction of business. Source: Uniform Law Commission, www.uniformlaws.org

[iii] 31 CFR 1010.100(hhh)

[iv] Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. “Application of FinCEN’s Regulations to Persons Administering, Exchanging, or Using Virtual Currencies.” FIN-2013-G001, 18 March 2013.

[v] Financial Actions Task Force. “Regulation of Virtual Assets.” 19 October 2018.

[vi] Financial Actions Task Force. “Public Statement – Mitigating Risks from Virtual Assets.” 22 February 2019.

[vii] Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. “Application of FinCEN’s Regulations to Certain Business Models Involving Convertible Virtual Currencies.” FIN-2019-G001, 9 May 2019.

[viii] Various codes are also required data on a Fedwire transfer; however, these codes are for system processing purposes and have no relation to originator or beneficiary data.

[ix] Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. “Funds ‘Travel’ Regulations: Questions and Answers.” FIN-2010-G004, 9 November 2010.

Schedule a free demo

See how alessa can help your organization.

100% Commitment Free

Recent Posts

Why PEP Screening is Critical for AML Compliance

PEP screening is a crucial component of an effective AML compliance program. Learn why your business needs to screen for PEPs and how Alessa can help.

Banking PEPs: How to Proactively Mitigate Screening Risks in the Banking Industry

Learn PEP screening best practices for banks, including using quality PEP lists, taking a risk-based approach, and leveraging AML technology solutions.

How to Reduce AML False Positives

Learn how to reduce AML false positives in your compliance programs and streamline your screening procedures to increase efficiency.

Sign up for our newsletter

Join the thousands of AML professionals who receive our monthly newsletter to stay on top of what is happening in the industry. You may opt-out at any time.

Customer Support

Customer Support Portal

1-844-265-2508 Ext. 5100

Copyright © 2023 Alessa Inc.

Please fill out the form to access the webinar:

The Federal Register

The daily journal of the united states government, request access.

Due to aggressive automated scraping of FederalRegister.gov and eCFR.gov, programmatic access to these sites is limited to access to our extensive developer APIs.

If you are human user receiving this message, we can add your IP address to a set of IPs that can access FederalRegister.gov & eCFR.gov; complete the CAPTCHA (bot test) below and click "Request Access". This process will be necessary for each IP address you wish to access the site from, requests are valid for approximately one quarter (three months) after which the process may need to be repeated.

An official website of the United States government.

If you want to request a wider IP range, first request access for your current IP, and then use the "Site Feedback" button found in the lower left-hand side to make the request.

- BSA/AML Manual

- Appendix D – Statutory Definition of Financial Institution

APPENDIX D: STATUTORY DEFINITION OF FINANCIAL INSTITUTION

As defined in the BSA 31 USC 5312(a)(2) , the term “financial institution” includes the following:

- An insured bank (as defined in section 3(h) of the FDI Act ( 12 USC 1813(h) )).

- A commercial bank or trust company.

- A private banker.

- An agency or branch of a foreign bank in the United States.

- Any credit union.

- A thrift institution.

- A broker or dealer registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 ( 15 USC 78a et seq.).

- A broker or dealer in securities or commodities.

- An investment banker or investment company.

- A currency exchange.

- An operator of a credit card system.

- An insurance company.

- A dealer in precious metals, stones, or jewels.

- A pawnbroker.

- A loan or finance company.

- A travel agency.

- A licensed sender of money or any other person who engages as a business in the transmission of funds, including any person who engages as a business in an informal money transfer system or any network of people who engage as a business in facilitating the transfer of money domestically or internationally outside of the conventional financial institutions system.

- A telegraph company.

- A business engaged in vehicle sales, including automobile, airplane, and boat sales.

- Persons involved in real estate closings and settlements.

- The United States Postal Service.

- An agency of the United States government or of a state or local government carrying out a duty or power of a business described in this paragraph.

- Is licensed as a casino, gambling casino, or gaming establishment under the laws of any state or any political subdivision of any state; or

- Is an Indian gaming operation conducted under or pursuant to the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act other than an operation that is limited to class I gaming (as defined in section 4 (6 ) of such act).

- Any business or agency which engages in any activity which the Secretary of the Treasury determines, by regulation, to be an activity that is similar to, related to, or a substitute for any activity in which any business described in this paragraph is authorized to engage.

- Any other business designated by the Secretary whose cash transactions have a high degree of usefulness in criminal, tax, or regulatory matters.

- Any futures commission merchant, commodity trading advisor, or commodity pool operator registered, or required to register, under the Commodity Exchange Act ( 7 USC 1 , et seq. ).

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Scoping and Planning

- BSA/AML Risk Assessment

- Assessing the BSA/AML Compliance Program

- Developing Conclusions and Finalizing the Exam

- Assessing Compliance with BSA Regulatory Requirements

- Office of Foreign Assets Control

- Program Structures

- Risks Associated with Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing

- Appendix 1 – Beneficial Ownership

- Appendix A – BSA Laws and Regulations

- Appendix B – BSA/AML Directives

- Appendix C – BSA/AML References

- Appendix E – International Organizations

- Appendix F – Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Red Flags

- Appendix G – Structuring

- Appendix H – Request Letter Items (Core and Expanded)

- Appendix I – Risk Assessment Link to the BSA/AML Compliance Program

- Appendix J – Quantity of Risk Matrix

- Appendix K – Customer Risk Versus Due Diligence and Suspicious Activity Monitoring

- Appendix L – SAR Quality Guidance

- Appendix M – Quantity of Risk Matrix – OFAC Procedures

- Appendix N – Private Banking – Common Structure

- Appendix O – Examiner Tools for Transaction Testing

- Appendix P – BSA Record Retention Requirements

- Appendix Q – Abbreviations

- Appendix R – Enforcement Guidance

- Appendix S – Key Suspicious Activity Monitoring Components

- Appendix T – BSA E-Filing System

Anti-Money Laundering Laws and Regulations USA 2023-2024

ICLG - Anti-Money Laundering Laws and Regulations - USA Chapter covers issues including criminal enforcement, regulatory and administrative enforcement and requirements for financial institutions and other designated businesses.

Chapter Content Free Access

1. the crime of money laundering and criminal enforcement, 2. anti-money laundering regulatory/administrative requirements and enforcement, 3. anti-money laundering requirements for financial institutions and other designated businesses.

1.1 What is the legal authority to prosecute money laundering at the national level?

Money laundering has been a crime in the United States since 1986, making the country one of the first countries to criminalise money laundering conduct. There are two money laundering criminal provisions; 18 United States Code, Sections 1956 and 1957 (18 U.S.C. §§ 1956 and 1957).

1.2 What must be proven by the government to establish money laundering as a criminal offence? What money laundering predicate offences are included? Is tax evasion a predicate offence for money laundering?

Generally, it is a crime to engage in virtually any type of financial transaction if a person conducted the transaction with knowledge that the funds were the proceeds of “criminal activity” and if the government can prove the proceeds were derived from a “specified unlawful activity”. Criminal activity can be a violation of any criminal law – federal, state, local, or foreign. Specified unlawful activities are set forth in the statute and include over 200 types of U.S. crimes, from drug trafficking, terrorism, and fraud, to crimes traditionally associated with organised crime, and certain foreign crimes, as discussed below in question 1.3.

The government does not need to prove that the person conducting the money laundering transaction knew that the proceeds were from a specified form of illegal activity.

Knowledge can be based on wilful blindness or conscious indifference – failure to inquire when faced with red flags for illegal activity. Additionally, knowledge can be based on a government “sting” or subterfuge, where government agents represent that funds are the proceeds of illegal activity.

Under Section 1956, the transaction can be: (1) with the intent to promote the carrying on of the specified unlawful activity; (2) with the intent to engage in U.S. tax evasion or to file a false tax return; (3) knowing the transaction is in whole or in part to disguise the nature, location, source, ownership or control of the proceeds of a specified unlawful activity; or (4) with the intent to avoid a transaction reporting requirement under federal or state law.

Section 1956 also criminalises the transportation or transmission of funds or monetary instruments (cash or negotiable instruments or securities in bearer form): (1) with the intent to promote the carrying out of a specific unlawful activity; or (2) knowing the funds or monetary instruments represent the proceeds of a specified unlawful activity and the transmission or transportation is designed in whole or in part to conceal or disguise the nature, location, source, ownership or control of the proceeds of the specified unlawful activity.

Under Section 1957, it is a crime to knowingly engage in a financial transaction in property derived from specified unlawful activity through a U.S. bank or other “financial institution”, or a foreign bank (in an amount greater than $10,000). Financial institution is broadly defined with reference to the Bank Secrecy Act (“BSA”) statutory definition of financial institution (31 U.S.C. § 5312(a)(2)), and includes not just banks but a wide range of other financial businesses, including securities broker-dealers, insurance companies, non-bank finance companies, and casinos.

Tax evasion is not itself a predicate offence, but, as noted, conducting a transaction with the proceeds of another specified unlawful activity with the intent to evade federal tax or file a false tax return is subject to prosecution under Section 1956. Also, wire fraud (18 U.S.C. § 1343) is a specified unlawful activity. Wire fraud to promote tax evasion, even foreign tax evasion, can be a money laundering predicate offence. See Pasquantino v. U.S. , 544 U.S. 349 (2005) (wire fraud to defraud a foreign government of tax revenue can be a basis for money laundering).

1.3 Is there extraterritorial jurisdiction for the crime of money laundering? Is money laundering of the proceeds of foreign crimes punishable?

There is extensive extraterritorial jurisdiction under the money laundering criminal provisions. Under Section 1956, there is extraterritorial jurisdiction over money laundering conduct (over $10,000) by a U.S. citizen anywhere in the world, or over a non-U.S. citizen if the conduct occurs at least “in part” in the United States. “In part” can be a funds transfer to a U.S. bank.

Under Section 1957, there is jurisdiction over offences that take place outside the United States by U.S. persons (citizens, residents, and legal persons) and by non-U.S. persons, as long as the transaction occurs in whole or in part in the United States.

Certain foreign crimes are specified unlawful activities, including drug crimes, murder for hire, arson, foreign public corruption, foreign bank fraud, arms smuggling, human trafficking, and any crime subject to a multilateral extradition treaty with the United States.

Generally, there is no extraterritorial jurisdiction under the BSA, discussed below in section 2. The BSA requirements for money services businesses (“MSBs”) can apply, however, even if the MSB has no physical presence in the United States but conducts business “wholly or in substantial part within the United States”, e.g. , if a substantial amount of the business of the MSB is based on U.S. customers. 31 C.F.R. § 1010.100(ff) (BSA definition of MSB).

1.4 Which government authorities are responsible for investigating and prosecuting money laundering criminal offences?

Prosecution of money laundering crimes is the responsibility of the Department of Justice. There is a special unit in the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice, the Money Laundering and Asset Recovery Section (“MLARS”), that is responsible for money laundering prosecution and related forfeiture actions. The 94 U.S. Attorney’s Offices across the United States and its territories may also prosecute the crime of money laundering alone or with MLARS. MLARS must approve any prosecution of a financial institution by a U.S. Attorney’s Office.

As required in Section 1956(e), there is a (non-public) memorandum of understanding among the Secretary of the Treasury, the Secretary of Homeland Security, the Attorney General, and the Postal Service setting forth investigative responsibilities of the various federal law enforcement agencies that have investigative jurisdiction over Sections 1956 and 1957. Jurisdiction is generally along the lines of the responsibility for the investigation of the underlying specified unlawful activity. The various federal agencies frequently work together on cases, sometimes along with state and local authorities, where jurisdiction overlaps.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the U.S. Secret Service, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Internal Revenue Service Criminal Division, and the Postal Inspection Service frequently conduct money laundering investigations. An investigation unit of the Environmental Protection Agency can investigate money laundering crimes relating to environmental crimes.

1.5 Is there corporate criminal liability or only liability for natural persons?

There is criminal liability for natural and legal persons.

1.6 What are the maximum penalties applicable to individuals and legal entities convicted of money laundering?

The maximum penalties are fines of up to $500,000 or double the amount of property involved, whichever is greater, for each violation; and for individuals, imprisonment of up to 20 years for each violation.

1.7 What is the statute of limitations for money laundering crimes?

The statute of limitations for money laundering crimes is five years. 18 U.S.C. § 3282(a).

1.8 Is enforcement only at national level? Are there parallel state or provincial criminal offences?

Section 1956(d) specifically provides that it does not supersede any provisions in federal, state or other local laws imposing additional criminal or civil (administrative) penalties.

Many states, including New York and California, also have parallel money laundering criminal provisions under state law. See , e.g. , New York Penal Law Article 470.

1.9 Are there related forfeiture/confiscation authorities? What property is subject to confiscation? Under what circumstances can there be confiscation against funds or property if there has been no criminal conviction, i.e., non-criminal confiscation or civil forfeiture?

There is both criminal forfeiture following a conviction for money laundering, and civil forfeiture against the assets involved in, or traceable to, money laundering criminal conduct.

Under 18 U.S.C. § 982, if a person has been convicted of money laundering, any property, real or personal, involved in the offence, or any property traceable to the offence, is subject to forfeiture.

Under 18 U.S.C. § 981, a civil forfeiture action can be brought against property involved in or traceable to the money laundering conduct even if no one has been convicted of money laundering. Because this is a civil action, the standard of proof for the government is lower than if there were a criminal prosecution for the money laundering conduct (preponderance of the evidence versus beyond a reasonable doubt). There is no need to establish that the person alleged to have committed money laundering is dead or otherwise unavailable.

1.10 Have banks or other regulated financial institutions or their directors, officers or employees been convicted of money laundering?

Absent established collusion with money launderers or other criminals, very few directors, officers, or employees have been convicted of money laundering. Recently, there have been criminal resolutions of money laundering cases against the principals of virtual currency exchanges where they were alleged to have engaged in money laundering or violations of AML requirements.

In most cases where there have been criminal settlements with banks and other financial institutions related to money laundering, the settlements have been based on alleged violations of the BSA, not violations of the money laundering criminal offences. There have been civil penalties against individual financial institution officers based on BSA violations.

If a bank is convicted of money laundering, subject to a required regulatory (administrative) hearing, the bank could lose its charter or federal deposit insurance, i.e. , be forced to cease operations. Such a review is discretionary if a bank is convicted of BSA violations and, in practice, is not conducted. See , e.g. , 12 U.S.C. § 1818(w) (process for state-licensed, federally insured banks). This authority has not been used to date.

1.11 How are criminal actions resolved or settled if not through the judicial process? Are records of the fact and terms of such settlements public?

Since 2002, over 40 financial institutions subject to AML regulatory requirements have pled guilty or have reached settlements with the Department of Justice, generally, as noted, based on alleged violations of the anti-money laundering (“AML”) regulatory requirements under the BSA ( e.g. , failure to maintain an adequate AML Program and/or failure to file required suspicious activity reports (“SARs”)). In December 2022, for instance, Danske Bank pled guilty to defrauding U.S. banks about the AML controls of its Estonian subsidiary and forfeited $2 billion to the United States. While this case is money-laundering related, it was based on the crime of bank fraud.

A few of the settlements with foreign-owned banks have been based on alleged sanctions violations in addition to BSA violations. Substantial fines or forfeitures were paid as part of these settlements. There were also two other BSA prosecutions of banks in the late 1980s relating to currency transaction reporting, and the Bank of Credit and Commerce International (“BCCI”) pled guilty to money laundering in 1990.

In connection with many of the criminal dispositions, civil (administrative) sanctions based on the same or related misconduct have been imposed at the same time by federal and/or state regulators and the Department of the Treasury Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (“FinCEN”) in a coordinated settlement. See questions 2.8–2.11.

Records relating to the criminal settlements are publicly available, including, in most cases, lengthy statements by the government about underlying facts that led to the criminal disposition. To our knowledge, there have been no non-public criminal settlements with financial institutions.

1.12 Describe anti-money laundering enforcement priorities or areas of particular focus for enforcement.

Pursuant to a statutory requirement in the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 (“AML Act”), codified at 31 U.S.C. § 5318(h)(4)(A), on June 30, 2021, FinCEN, in consultation with the Department of Justice, issued AML and Countering the Financing of Terrorism National Priorities, available at [Hyperlink] . The priorities were listed (in no particular order) as: corruption; cybercrime, including cybersecurity and virtual currency; terrorist financing; fraud; transnational criminal organisation activity; drug trafficking; human trafficking/human smuggling; and proliferation financing. FinCEN and the federal bank regulators are working on proposed regulations regarding how financial institutions should incorporate these priorities into their AML Programs.

2.1 What are the legal or administrative authorities for imposing anti-money laundering requirements on financial institutions and other businesses? Please provide the details of such anti-money laundering requirements.

Authorities

In the United States, the main AML legal authority is the BSA, 31 U.S.C. § 5311 et seq. , 12 U.S.C. §§ 1829b and 1951–1959 (the “BSA statute”), and the BSA implementing regulations, 31 C.F.R. Chapter X (the “BSA regulations”). (The BSA statute and regulations collectively will be referred to as “the BSA”.) The BSA statute was originally enacted in 1970 and has been amended several times, including significantly in 2001 by the USA PATRIOT Act (“PATRIOT Act”) and, most recently, by the AML Act. The BSA gives the Secretary of the Treasury the authority to implement reporting, recordkeeping, and AML Program requirements by regulation for financial institutions and other businesses listed in the statute. 31 U.S.C. § 5312(a)(2). The BSA is administered and enforced by a Department of the Treasury bureau, FinCEN. FinCEN is also the U.S. Financial Intelligence Unit (“FIU”). See question 2.6. Because FinCEN has no examination staff, it has further delegated BSA examination authority for various categories of financial institutions to their federal functional regulators (federal bank, securities, and futures regulators). Examination authority for financial institutions and businesses without a federal functional regulator is discussed in question 2.5.

The federal banking regulators (the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (the “OCC”), the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve (“Federal Reserve”), the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (“FDIC”), and the National Credit Union Administration (“NCUA”)) have parallel regulatory authority to require BSA compliance programs and suspicious activity reporting for the institutions for which they are responsible. See , e.g. , 12 C.F.R. §§ 21.21 (OCC BSA Program requirement), 21.12 (OCC suspicious activity reporting requirement). Consequently, the bank regulators have both delegated examination authority from FinCEN, as federal functional regulators, and independent regulatory enforcement authority.

BSA examination authority for broker-dealers has been delegated to the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”), as the federal functional regulator for broker-dealers. The SEC has further delegated authority to the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (“FINRA”), the self-regulatory organisation (“SRO”) for broker-dealers. The SEC has also incorporated compliance with the BSA requirements for broker-dealers into SEC regulations and, consequently, has independent authority to enforce the BSA. 17 C.F.R. §§ 240.17a-8, 405.4.

Similarly, BSA examination authority for futures commission merchants (“FCMs”) and introducing brokers in commodities (“IB-Cs”), which are financial institutions under the BSA, has been delegated by FinCEN to the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC”) as their federal functional regulator. The CFTC has also incorporated BSA compliance into its regulations. 17 C.F.R. § 42.2. The CFTC has delegated authority to the National Futures Authority (“NFA”) as that industry’s SRO.

AML requirements

For the United States, the response to the question of what requirements apply is complicated. Generally, the BSA statute is not self-executing and must be implemented by regulation. The scope and details of regulatory requirements for each category of financial institutions and financial businesses subject to the BSA vary. To further complicate the issue, all these businesses are defined as financial institutions under the BSA statute, but only certain ones are designated as financial institutions under the BSA regulations, i.e. , banks, broker-dealers, FCMs, IB-Cs, mutual funds, MSBs, casinos, and card clubs. Some BSA requirements only apply to businesses that fall within the BSA regulatory definition of financial institution.

There are also three BSA requirements that apply to all persons subject to U.S. jurisdiction or to all U.S. trades and businesses, not just to financial institutions or other businesses subject to specific BSA regulatory requirements. See question 3.16.

Main requirements

These are the main requirements under the BSA regulations, most of which are discussed in more detail in Section 3 of this chapter, as cross-referenced below:

- AML Programs : All financial institutions and financial businesses subject to the BSA regulations are required to maintain risk-based AML Programs with certain minimum requirements to guard against money laundering. See question 3.5.

- Currency Transaction Reporting : “Financial institutions”, as defined under the BSA regulations, must file Currency Transaction Reports (“CTRs”). See question 3.6.

- Cash Reporting or Form 8300 Reporting : This requirement applies to all other businesses that are subject to the AML Program requirement, but not defined as financial institutions under the BSA regulations, and all other U.S. trades and businesses. See questions 3.6 and 3.16.

- Suspicious Transaction Reporting : Most financial institutions and other businesses subject to the AML Program requirement must file SARs. See question 3.11.

- Customer Due Diligence (“CDD”) Program and Customer Identification Program (“CIP”) : Banks, broker-dealers, FCMs, IB-Cs, and mutual funds are required to maintain CDD Programs as part of their AML Programs, which include a CIP. See question 3.9.

- CDD Programs for Non-U.S. Private Banking Clients and Foreign Correspondents : This requirement is applicable to banks, broker-dealers, FCMs, IB-Cs, and mutual funds. See question 3.9.

- Recordkeeping : There are BSA general recordkeeping requirements applicable to all BSA financial institutions, specific recordkeeping requirements for specific types of BSA financial institutions, and requirements to maintain records related to BSA compliance for all financial institutions and financial businesses subject to the BSA. Generally, records are required to be maintained for five years. 31 C.F.R. § 1010.410 (general recordkeeping requirements for financial institutions); see , e.g. , 31 C.F.R. § 1023.410 (recordkeeping requirements for broker-dealers).

- Cash Sale of Monetary Instruments : There are special recordkeeping and identification requirements relating to the cash sale of monetary instruments in amounts of $3,000 to $10,000 inclusive (bank cheques or drafts, cashier’s cheques, travellers’ cheques, and money orders) by banks and other financial institutions under the BSA regulations. 31 C.F.R. § 1010.415.

- Funds Transfer Recordkeeping and the Travel Rule : This is applicable to banks and other financial institutions under the BSA regulations. See question 3.14.

- MSB Registration : MSBs must register (and re-register every two years) with FinCEN. MSBs that are only MSBs because they are agents of another MSB are not required to register. MSBs must maintain lists of their agents with certain information and provide the lists to FinCEN upon request. Sellers of prepaid access (unless MSBs by virtue of other business activities) are excepted from registration. 31 C.F.R. § 1022.380.

- Government Information Sharing or Section 314(a) Sharing : Periodically and on an ad hoc basis, banks, broker-dealers, and certain large MSBs receive lists from FinCEN of persons suspected of terrorist activity or money laundering by law enforcement agencies. The financial institutions must respond with information about accounts maintained for the persons and certain transactions conducted by them in accordance with guidance from FinCEN that is not public. The request and response are sent and received via a secure network. Strict confidentiality is required about the process. 31 C.F.R. § 1010.520.

- Voluntary Financial Institution Information Sharing or Section 314(b) Sharing : Financial institutions or other businesses required to maintain AML Programs under the BSA regulations and associations of financial institutions may voluntarily register with FinCEN to participate in sharing information with each other. The request can only be made for the purpose of identifying and/or reporting activity that the requestor suspects may be involved in terrorist activity or money laundering. The information received may only be used for SAR filing, to determine whether to open or maintain an account or conduct a transaction, or for use in BSA compliance. Strict confidentiality about the process must be maintained by participants. If all requirements are satisfied, there is a safe harbour from civil liability based on the disclosure. 31 C.F.R. § 1010.540.