What is Amenity? Meaning, Origin, Popular Use, and Synonyms

What is Amenity?

An amenity refers to a feature or service that enhances comfort, convenience, and enjoyment for travelers during their stay at accommodations or while visiting public places. Amenities can vary widely, ranging from essential offerings such as Wi-Fi, air conditioning, and complimentary toiletries to luxurious perks like spa facilities, swimming pools, and fine dining restaurants. These add-ons are designed to elevate the overall guest experience and make the stay more pleasant and memorable.

Origins of the term Amenity

The term “ amenity ” traces its roots back to the Latin word “amoenus,” which means “pleasant” or “delightful.” Over time, the word evolved and found its way into the English language, where it came to signify anything that adds to the comfort and enjoyment of a particular place or environment. In the context of travel and hospitality, amenities have become a critical aspect of accommodations and public spaces, contributing to the overall satisfaction of travelers.

Where is the term Amenity commonly used?

The term “amenity” is widely used in the travel and hospitality industry . It is frequently mentioned in hotel descriptions, vacation rental listings, and travel websites to highlight the facilities and services available to guests. Additionally, public spaces such as airports, train stations, and tourist attractions often promote their amenities to attract and cater to travelers.

Synonyms of the term Amenity

While “amenity” is the standard term used, there are some synonymous expressions that convey a similar concept:

- Facility: Emphasizing the availability of various features and conveniences.

- Perk: Referring to additional benefits or advantages offered to guests.

- Feature: Highlighting specific attributes that enhance the guest experience.

Definition of amenity

Examples of amenity in a sentence.

These examples are programmatically compiled from various online sources to illustrate current usage of the word 'amenity.' Any opinions expressed in the examples do not represent those of Merriam-Webster or its editors. Send us feedback about these examples.

Word History

Middle English amenite , from Latin amoenitat-, amoenitas , from amoenus pleasant

14th century, in the meaning defined at sense 3a

Dictionary Entries Near amenity

Cite this entry.

“Amenity.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/amenity. Accessed 30 May. 2024.

Kids Definition

Kids definition of amenity, more from merriam-webster on amenity.

Nglish: Translation of amenity for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of amenity for Arabic Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

More commonly misspelled words, commonly misspelled words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), absent letters that are heard anyway, how to use accents and diacritical marks, popular in wordplay, pilfer: how to play and win, the words of the week - may 24, 9 superb owl words, 10 words for lesser-known games and sports, your favorite band is in the dictionary, games & quizzes.

What Does Amenities Mean in Tourism?

By Anna Duncan

When planning a vacation, one of the key factors that travelers consider is the amenities offered by their chosen accommodation. Amenities are the extra features and services that hotels, resorts, and other tourism establishments provide to enhance their guests’ experience. These can range from basic facilities such as Wi-Fi and parking to luxurious perks like spas and private beaches.

Types of Amenities

There are various types of amenities that hotels and resorts can offer to cater to different preferences and needs of their guests. Some common examples include:

- Accommodation Amenities: These are the basic facilities provided in a guest room such as comfortable bedding, air conditioning, TV, and mini-fridge.

- Food and Beverage Amenities: This includes complimentary breakfast, room service, on-site restaurants or bars, coffee makers in rooms.

- Recreational Amenities: These amenities are provided for entertainment purposes such as swimming pools, gyms, sports courts or fields.

- Wellness Amenities: These include fitness centers or yoga studios, spas or massage services, saunas or steam rooms.

- Business Amenities: For business travelers these include conference rooms, printers/fax machines/scanners provided by the hotel.

The Importance of Offering Quality Amenities

Providing top-notch amenities has become a crucial aspect for tourism establishments to attract potential guests. With more competition in the market than ever before it’s essential for hotels to stand out from their competitors. By offering high-quality amenities at an affordable price point not only helps in attracting new customers but also creating loyal customers who may choose your establishment again over others.

The quality of amenities offered also plays a significant role in customer satisfaction. By providing a memorable experience, guests are more likely to leave positive reviews and recommend your establishment to others.

In conclusion, amenities have become an essential component of the tourism industry. They play a significant role in attracting new customers, creating loyal ones, and improving customer satisfaction.

9 Related Question Answers Found

What is mean by amenities in tourism, what are the example of amenities in tourism, what are tourism amenities, what jobs does tourism create, what benefits tourism brings to individuals and society, what does recreation mean in tourism, what are social benefits of tourism, what are the service characteristics of tourism, what does attractions mean in tourism, backpacking - budget travel - business travel - cruise ship - vacation - tourism - resort - cruise - road trip - destination wedding - tourist destination - best places, london - madrid - paris - prague - dubai - barcelona - rome.

© 2024 LuxuryTraveldiva

Know What to Expect From Hotel Amenities

When you’re staying at a hotel domestically or abroad, your guest stay often includes a few additional amenities. These extra services or products are given to hotel guests at no extra charge and can broadly include such items as shampoo, conditioner, body lotion, soaps, specialty candies, and the like. Amenities can also refer to a service like a printing station in the hotel lobby, access to a hotel pool or spa, or even free parking for hotel guests.

Most hotels in the United States offer the basic amenities like soap and toothpaste, free coffee and perhaps a continental breakfast, and some discounts to local restaurants, bars, and entertainment venues for guests of the hotel. However, depending on how deluxe the hotel suite is, you may receive even more of these extra surprise and delight treats.

In a 2014 poll by the Huffington Post , the publication determined that the top 10 amenities offered by hotels, according to hotel guests, are complimentary breakfast, an on-site restaurant offering guest discounts, free internet and Wi-Fi, free parking, 24-hour front desk service, a smoke-free facility, a swimming pool, an on-site bar, air conditioning throughout the building, and coffee or tea in the lobby—in that order.

Amenities: From Common to Luxe

Most hotel rooms offer a standard level of service including a bed, a mini-fridge, a shower and bath , and air conditioning (if you’re in America), but anything in addition to these standard price points are considered amenities and used as selling points between differing hotel chains.

Hair dryers, ironing boards, televisions, in-room internet access, ice machines, and towels, though typically included in most hotel rooms in the United States, are in fact considered amenities. Ovens, stoves, kitchen sinks, refrigerators, microwaves, and other kitchenette items are rarer in modern hotel rooms, though most do at least come with some way to keep your leftovers cool.

In recent years, indoor pools, gyms, and other means of exercise on-site are become more and more popular, with long-established hotel chains renovating their locations to include these deluxe amenities to draw even more guests to use their accommodations. Other hotels now even offer recreational activities like tennis, golf, and beach volleyball to their guests.

What to Know Before You Go

Although amenities are obviously not necessary to a successful night’s rest, they can certainly help ease your stay. Most hotels list their amenities online, but you can always ask your booking agent before you rent a room for the night.

If you’re simply looking for a nice hotel to rest for the night and don’t plan to arrive early or stick around late the next morning, there’s not much you’ll need in the way of amenities, so you can often save a few dollars by booking a hotel with fewer extras—although these hotels say amenities are not included in the price, the more amenities a hotel has, the more they can justifiably charge guests to stay with them.

If instead you’re booking far in advance and plan to stay multiple nights or base your vacation on the amenities featured at a particular hotel, inn, lodge, or other accommodation, you will definitely want to know exactly what’s offered both in the room and at the hotel facility itself.

What Can You Take From a Hotel, and What Is Stealing?

AAA Diamond Ratings

Best Hotel Chains for Large Families

Best Budget Disney World Hotels

The Best Places to Stay When Going to Cedar Point Amusement Park

Best Budget Manhattan Hotels

The Best Oceanfront Virginia Beach Hotels

Hotels at Foxwoods Casino in Connecticut

The Best Oregon Coast Hotels

How to Stay at a Ryokan

Top 9 Hotels in Heidelberg

Best Disneyland Hotels

The Best Key West Beachfront Hotels

11 Family Hotels with Amenities Just for Kids

11 Cool Features at Universal's Cabana Bay Resort

10 Hotel Add-On Charges to Avoid

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 3. Accommodation

Rebecca Wilson-Mah

Learning Objectives

- Explain the contribution the accommodations sector makes to Canada’s economy

- Identify how a hotel category is determined, and describe different hotel categories in Canada

- Explain the meaning and structure of independent ownership, franchise agreements, and management contracts

- Summarize current accommodation trends

- Discuss the structure of hotel operations

In essence, hospitality is made up of two services: the provision of overnight accommodation for people travelling away from home, and options for people dining outside their home. We refer to the accommodation and food and beverage services sectors together as the hospitality industry. This chapter explores the accommodation sector, and the Chapter 4 details the food and beverage sector.

In Canada, approximately 25% to 35% of visitor spending is attributed to accommodation, making it a substantial portion of travel expenditures.

There were 8,090 hotel properties with a total of 440,123 rooms in Canada in 2014. Direct spending on overnight stays was $16.7 billion, and the year’s average occupancy rate was forecast at 64%. Across the country the sector employed 287,000 people (Hotel Association of Canada, 2014). According to go2HR, “with a projected rate of annual employment growth of 1.5 per cent, there will be 18,920 job openings between 2011 and 2020” (2015a).

In order to understand this large and significant sector, we will explore the history and importance of hotels in Canada, and review the hotel types along with various ownership structures and operational considerations. To complete the chapter, we will identify accommodation alternatives and specific trends that are affecting the accommodation sector today.

Spotlight On: The Hotel Association of Canada

The Hotel Association of Canada (HAC) is the national trade organization advocating on behalf of over 8,500 hotels. Founded over 100 years ago, the association also provides professional development resources, discounts with vendors, and industry research including statistics monitoring and an extensive member database. For more information, visit the Hotel Association of Canada website : www.hotelassociation.ca

The History of Hotels in Canada

As we learned in Chapter 2, travel in Europe, North America, and Australia developed with the establishment of railway networks and train travel in the mid-1800s. The history of Canada’s grand hotels is also the story of Canada’s ocean liners and railways. Until the use of personal cars became widespread in the 1920s and 1930s, and taxpayer-funded all-weather highways were created, railways were the only long-distance land transportation available in Canada.

Both of Canada’s railway companies established hotel divisions: Canadian Pacific Hotels and Canadian National Hotels (Canada History, 2013). The first hotels were small and included Glacier House in Glacier National Park, BC, and Mount Stephen House in Field, BC. The hotel business was firmly established when both companies recognized the business opportunity in the growth of tourism, and they soon became rivals, building grand hotels in select locations close to railway stops.

Spotlight On: Canadian Pacific Hotels

Under the guidance of Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) chief engineer and visionary William Cornelius Van Horne, a hotel empire was born (Canada History, 2013). Van Horne was a pioneer of tourism, and like Thomas Cook in the UK, he saw the potential for tourism that was made possible by the railway. Van Horne was famously quoted in 1886, “If we can’t export the scenery, we’ll import the tourists.” In 1999, many historic CPR properties joined the Fairmont brand. For more information, visit the Fairmont website : www.fairmont.com/about-us/ourhistory/

Banff Springs Hotel opened in 1888, and other hotels soon followed, including the Château Frontenac in Quebec City (1893), the Royal York in Toronto (1929), and the Hotel Vancouver (1939). These hotels remain in operation today and are landmarks in their destinations, functioning as accommodations and as local attractions due to their historic significance and outstanding architecture.

Through the 1950s and 1960s, an increase in motor traffic saw the rise of the motel. The word motel, used less commonly today, comes from the term “motorist’s hotel,” used to denote a hotel that provides ample parking and rooms that are easily accessible from the parking lot. Traditionally, these structures were designed with all the rooms facing the parking lot, and relied heavily on motor traffic from nearby highways (Diffen, 2015).

Today, there are a number of hotel types, which can be classified in multiple ways. Let’s explore these classifications in more detail.

Hotel Types

Hotels are typically referred to by hotel type or category. The type of hotel is determined primarily by the size and location of the building structure, and then by the function, target market, service level, other amenities, and industry standards.

Take a Closer Look: Hotelier

The magazine Hotelier , available online and in eight annual print editions, is a resource relied on by many industry professionals across Canada. Featuring profiles of successful hoteliers, information about specific brands and properties, and hosting events including a speaker series, Hotelier is a good resource for students wanting more information about the sector in a dynamic format. Read press releases, find out about upcoming events, and subscribe at the Hotelier Magazine website : www.hoteliermagazine.com

Classifications

Competitive set is a marketing term used to identify a group of hotels that include the competitors that a hotel guest is likely to consider as an alternative. These can be grouped by any of the classifications listed in Table 3.1, such as size, location, or amenities offered. There must be a minimum of three hotels to qualify as a competitive set.

Business hotels, airport hotels, budget hotels, boutique hotels, convention hotels, and casino hotels are some examples of differentiated hotel concepts and services designed to meet a specific market segment. As companies continue to innovate and compete to capture defined niche markets within each set, we can expect to see the continued expansion of specific concepts. For example, hotels found close to, or even within, convention facilities are a great match for meetings and events, as well as the SMERF market (social, military, educational, religious, and fraternal segment of the group travel market).

Spotlight On: BC Hotel Association

The BC Hotel Association (BCHA) represents over 600 members and 200 associate members — accounting for 80,000 rooms and more than 60,000 employees. The association produces an annual industry trade show and seminar series, and publishes InnFocus magazine for professionals in the trade. For more information, visit the BC Hotel Association website : www.bchotelassociation.com

Table 3.2 outlines the characteristics of specific hotel types that have evolved to match the needs of a particular traveller segment. As you can see, hotels adapt and diversify depending on the markets they want and need to attract to stay in business.

Let’s now take a closer look at three types of hotel that have emerged to meet specific market needs: budget hotels, boutique hotels, and resorts.

Budget Hotels

The term budget hotel is challenging to define, however most budget properties typically have a standardized appearance and offer basic services with limited food and beverage facilities. Budget hotels were first developed in the United States and built along the interstate highway system. The first Holiday Inn opened in the United States in 1952; the first Quality Motel followed in 1963.

In Europe, Accor operates the predominant European-branded budget rooms. Accor has four hotel brands that were recently redesigned: hotelF1, ibis budget, ibis Styles, and ibis. These budget brands offer comfort, modern design, and breakfast on site; ibis Styles is all inclusive, with one price for room night, breakfast, and internet access (Accor, 2015).

The budget brands owned by Accor are an example of a shift toward the budget boutique hotel style. A relatively new category of hotel, budget boutique is a no-frills boutique experience that still provides style, comfort, and a unique atmosphere. Starwood has entered this category with a scaled down version of W with the new Aloft brand that debuted in Montreal in 2008 (Starwood Hotels, 2011).

Boutique Hotels

Canada currently has no industry standards to define boutique hotels, but these hotels generally share some common features. These include having less than 100 rooms and featuring a distinctive design style and on-site food and beverage options (Boutique Hotel Association, n.d.). As a reflection of the size of the hotel, a boutique hotel is typically intimate and has an easily identifiable atmosphere, such as classic, luxurious, quirky, or funky.

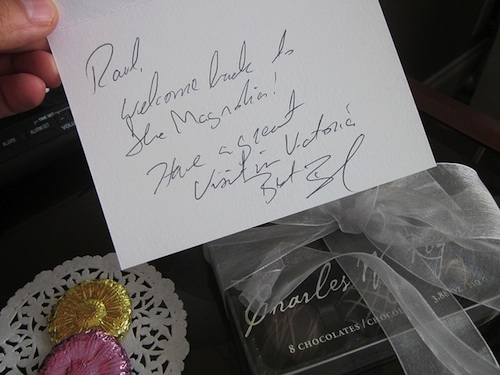

According to Bill Lewis, general manager for the Magnolia Hotel and Spa in Victoria, “guests seek out boutique hotels for their small size, individual design style, … and personalized service.” He feels that “maintaining this service level in a small hotel allows for a very personalized and intimate experience that cannot be matched in large branded hotels” (personal communication, 2014).

A resort is a full-service hotel that provides access to or offers a range of recreation facilities and amenities. A resort is typically the primary provider of the guest experience and will generally have one signature amenity or attraction (Brey, 2009).

Examples of signature amenities include skiing and mountains, golf, beach and ocean, lakeside, casino and gaming, all inclusiveness, spa and wellness, marina, tennis, and waterpark. In addition, resorts also offer secondary experiences and a leisure or retreat-style environment.

Take a Closer Look: Condé Nast Best Hotels and Resorts in Canada 2014

Condé Nast Traveler and the CN publishing family have many well-regarded “best of” lists, one of which is the Best Hotels and Resorts in Canada. In 2014, three of the top 10 were in BC, with the Wickaninnish Inn and Black Rock Oceanfront Resort earning first and second place. You can read the rest of the list at, “The Best Hotels and Resorts in Canada: 2014” : www.cntraveler.com/gold-list/2014/americas/canada

Now that we understand the classifications of hotel types, let’s gain a deeper understanding of the various ownership structures in the industry.

Ownership Structures

There are several ownership models employed in the sector today, including independent, management contract, chains and franchise agreements, fractional ownership, and full ownership strata units. This section explains each of these in more detail and provides examples of each.

Independent

An independent hotel is financed by one individual or a small group and is directly managed by its owners or third-party operators. The term independent refers to a management system that is free from outside control.

There are a number of very well-established independently branded hotels. These hotel companies have developed their own standards, support systems, policies and procedures, and best practices in all areas of the business. Independent hotels have the flexibility to customize or adjust their systems to position their property for success, and the location, product, service, experience, sales and marketing, and brand are all necessary for that success (Cabañas, 2014). An example of an independent hotel is the Wedgewood Hotel and Spa in Vancouver, founded by Eleni Skalbania, and currently co-owned by her daughter Elpie (Wedgewood, 2015).

Management Contract

Another business model is a management contract. This is a service offered by a management company to manage a hotel or resort for its owners. Owners have two main options for the structure of a management contract. One is to enter into a separate franchise agreement to secure a brand and then engage an independent third-party hotel management company to manage the hotel. SilverBirch Hotels is an example of a hotel management company that manages independent hotels and hotels operating under different major franchise brands, such as Marriott, Hilton, and Radisson (SilverBirch Hotels, 2015).

A slightly different option is for owners to select a single company to provide the brand and the expertise to manage the property. Four Seasons Hotels and Resorts and Fairmont Hotels and Resorts are companies that provide this option to owners. In 2014, the iconic Fairmont Empress hotel was purchased by Vancouver developer Nat Bosa and his wife Flora, who continued to retain Fairmont as the management company after the purchase (Meiszner, 2014).

Selecting a brand affiliation is one of the most significant decisions hotel owners must make (Crandell, Dickinson, & Kante, 2004). The brand affiliation selected will largely determine the cost of hotel development or conversion of an existing property to meet new brand standards. The affiliation will also determine a number of things about the ongoing operation including the level of services and amenities offered, cost of operation, marketing opportunities or restrictions, and the competitive position in the marketplace. For these reasons, owners typically consider several branding options before choosing to operate independently or selecting a brand affiliation.

Chains and Franchise Agreements

Another managerial and ownership structure is franchising. A hotel franchise enables individuals or investment companies (the franchisee ) to build or purchase a hotel and then buy or lease a brand name to operate a business and become part of a chain of hotels using the franchisor ’s hotel brand, image, goodwill, procedures, controls, marketing, and reservations systems (Rushmore, 2005).

A well-known franchise in BC is Coast Hotels. A franchisee with Coast Hotels becomes part of a network of properties that use a central reservations system with access to electronic distribution channels, regional and national marketing programs, central purchasing, and brand operating standards (Coast Hotels, 2015). A franchisee also receives training, support, and advice from the franchisor and must adhere to regular inspections, audits, and reporting requirements.

Selecting a franchise structure may reduce investment risk by enabling the franchisee to associate with an established hotel company. Franchise fees can be substantial and a franchisee must be willing to adhere to the contractual obligations with the franchisor (Migdal, n.d.; and Rushmore, 2005). Franchise fees typically include an initial fee paid with the franchise application, and then continuing fees paid during the term of the agreement. These fees are sometimes a percentage of revenue but can be set at a fixed fee. Franchise fees generally range from 4% to 7% of gross rooms revenue (Crandell et al., 2004).

Fractional Ownership

In a fractional ownership model, developers finance hotel builds by selling units in one-eighth to one-quarter shares. This financing model was very popular in BC from the late 1990s to 2008 (Western Investor, 2012). Examples of fractional ownership include the Sun Peaks Ski Resort in Kamloops and the Penticton Lakeside Resort.

In this model, owners can place their unit in a rental pool. The investment return for owners is based on the term

s of the contract they have for their unit, the strata fees, and the hotel’s occupancy. Managing fractional ownership can be very time consuming for hotel owners or management companies as each hotel unit can have up to eight owners. If occupancy rates are too low, an owner may not be able to cover the monthly strata fees. For the hotel management company, attaining occupancy rate targets is necessary to ensure that the balance of revenue is sufficient to cover the hotel’s operating expenses.

Developers now anticipate that fractional ownership will not be used to finance new hotel builds in the future due to poor performance. There have been some high-profile collapses for hotel developers in BC, and between 2002 and 2012 fractional hotel owners experienced asset depreciation (Western Investor, 2012). It is uncertain how the market will perform in the next several years.

Full Ownership Strata Units

In this financing model, hotel developers finance a new hotel build with the sale of full ownership strata units. The sale of the condominium units finances the hotel development. Examples include the Fairmont Pacific Rim and the Rosewood Hotel Georgia.

Spotlight On: The BC Hospitality Foundation

The BC Hospitality Foundation (BCHF) was created to help support hospitality (accommodation and food and beverage) professionals in their time of need. It has expanded to become a provider of scholarships for students in hospitality management and culinary programs. To raise funds for these initiatives, the foundation hosts annual events including Dish and Dazzle and a golf tournament. For more information, visit the BC Hospitality Foundation website : bchospitalityfoundation.com

No matter what the ownership model, it’s critical for properties to offer a return on investment for owners. The next section looks at ways of measuring financial performance in the sector.

Financial Performance

According to hotel consultant Betsy McDonald from HVS International Hotel Consultancy, the “industry rule of thumb is that a hotel room must make $1 per night for every $1,000 it takes to build or buy. If the hotel costs $125,000 per [room], the room has to rent for $125 per night on average and you need 60% to 70% occupancy to break even” (McDonald, 2011).

Several terms and formulas are used to evaluate revenue management strategies and operational efficiency:

Occupancy is a term that refers to the percentage of all guest rooms in the hotel that are occupied at a given time.

Average daily rate (ADR) is a calculation that states the average guest room income per occupied room in a given time period. It is determined by dividing the total room revenue by the number of rooms sold.

Revenue per available room (RevPAR ) is a calculation that combines both occupancy and ADR in one metric. It is calculated by multiplying a hotel’s ADR by its occupancy rate. It may also be calculated by dividing a hotel’s total room revenue by the total number of available rooms and the number of days in the period being measured.

Costs per occupied room (COPR) is a figure that states all the costs associated with making a room ready for a guest (linens, cleaning costs, guest amenities).

These terms and measurements allow hotel staff and management to track the success of the operation and to compare against competitors and regional averages.

Table 3.3 indicates the top five hotel companies in Canada based on revenue (Hotel Association of Canada, 2014). Note that the top two listings include units and revenues earned outside of Canada as these are international companies.

Across all ownership models, most properties have operational aspects in common. But before we take a closer look at the roles within a typical hotel, let’s review an important part of the accommodations sector in Canada and BC: camping and recreational vehicle (RV) stays.

Camping and RV Accommodation

A significant portion of travel accommodation is also provided in campgrounds and recreational vehicles (RVs). As the Canadian and BC tourism brands are closely tied to the outdoors, and these are two options that immerse travellers in the outdoor experience, it is no surprise that these two types of accommodation are popular options.

In 2011, 14% of Canadian households owned an RV, with over 1 million RVs on the road in the country that year. Economic activity associated with RVing generated approximately $14.5 billion. Across the country 3,000 independently owned and operated campgrounds welcomed guests for camping in RVs and in tents that year (CNW, 2014).

Spotlight On: Camping and RVing British Columbia Coalition

The Camping and RVing British Columbia Coalition (CRVBCC) represents campground managers and brings together additional stakeholders including the Recreation Vehicle Dealers Association of BC and the Freshwater Fisheries Society. Their aim is to increase the profile of camping and RV experiences throughout BC, achieving this through a website, a blog, and media outreach. For more information, visit the Camping and RVing British Columbia Coalition website : www.campingrvbc.com

According to the Camping and RVing British Columbia Coalition (CRVBCC, 2014), BC is home to 340 vehicle accessible campgrounds managed by the BC Society of Park Facility Operators, and Destination British Columbia inspects and approves over 500 campgrounds across the province. Seven national parks within the province contain an additional 14 campgrounds, and the BC Recreation Sites and Trails Branch manages more than 1,200 backcountry sites including campgrounds and other facilities. Another 300 private RV parks and campgrounds play host to a mixture of longer-stay residents and overnight guests.

Spotlight On: the BC Lodging and Campgrounds Association

The BC Lodging and Campgrounds Association (BCLCA) was founded in 1944 to represent the interests of independently owned campgrounds and lodges. It provides advocacy and collaborative marketing, and promotes best practice among members. For more information, visit the BC Lodging and Campgrounds Association website : www.travel-british-columbia.com

In 2014, national industry associations began to call on the government for taxation relief and marketing help to ensure this segment of the sector could continue to thrive. They also highlighted the need to increase the operating hours and seasons of publicly funded campgrounds to match the private sector and to ensure continuity of service for guests (CNW, 2014). Closer to home, the BCLCA (see Spotlight On above) continues to advocate for equitable property tax arrangements, support with employment issues, and other policies relating to land and water use for their members.

Chapter 5 provides more in-depth information about the importance of the recreation sector to BC. For now, let’s move our discussion forward by taking a closer look at the common organizational structure of many accommodation businesses.

The organizational structures of operations and the number of roles and levels of responsibility vary depending on the type and size of accommodation. They are also determined by ownership and the standards and procedures of the management company. In this section, we explore the organizational structure and roles that are typically in place in a full-service hotel with under 500 rooms. These can also apply to smaller properties and businesses such as campgrounds — although in these cases several roles might be fulfilled by the same person.

Guest Services

Before we turn to examples of specific operational roles, let’s take a brief look at the importance of guest services, which will be covered in full in Chapter 9.

The accommodation sector provides much more than tangible products such as guest rooms, beds and meals; service is also crucial. Regardless of their role in the operation, all employees must do their part to ensure that each guest’s needs, preferences, and expectations are met and satisfied.

In some cases, such as in a luxury hotel, resort hotel, or an all-inclusive property, the guest services may represent a person’s entire vacation experience. In other cases, the service might be less significant, for example, in a budget airport hotel where location is the key driver, or a campground where guests primarily expect to take care of themselves.

In all cases, operators and employees must recognize and understand guest expectations and also what drives their satisfaction and loyalty. When the key drivers of guest satisfaction are understood, the hotel can ensure that service standards and business practices and policies support employees to deliver on these needs and that guest expectations are satisfied or exceeded.

Spotlight On: 4Hoteliers

4Hoteliers compiles world news for hotel, travel, and hospitality professionals. It features recent news releases and articles and a free e-newsletter distributed three times per week. For more information, or to subscribe, visit the 4Hoteliers website : www.4hoteliers.com

General Manager and Director of Operations

In most properties, the general manager or hotel manager serves as the head executive. Division heads oversee various departments including managers, administrative staff, and line-level supervisors. The general manager’s role is to provide strategic leadership and planning to all departments so revenue is maximized, employee relations are strong, and guests are satisfied.

The director of operations is responsible for overseeing the food and beverage and rooms division. This role is also responsible for providing guidance to department heads to achieve their targets and for directing the day-to-day operations of their respective departments. The director of operations also assumes the responsibilities of the general manager when he or she is absent from the property.

The controller is responsible for overall accounting and finance-related activities including accounts receivable, accounts payable, payroll, credit, systems management, cash management, food and beverage cost control, receiving, purchasing, food stores, yield management, capital planning, and budgeting.

Engineering and Maintenance

The chief engineer is the lead for the effective operation and maintenance of the property on a day-to-day basis, typically including general maintenance, heating, ventilation and air conditioning, kitchen maintenance, carpentry, and electrical and plumbing (Fairmont Hotels and Resorts, 2015). The chief engineer is also responsible for preventive maintenance and resource management programs.

Food and Beverage Division

The food and beverage director is responsible for catering and events, in-room dining, and stand-alone restaurants and bars. The executive chef, the director of banquets, and the assistant managers responsible for each restaurant report to the director of food and beverage. The director assists with promotions and sales, the annual food and beverage budget, and all other aspects of food and beverage operations to continually improve service and maximize profitability.

Human Resources

The human resources department provides guidance and advice on a wide range of management-related practices including recruitment and selection, training and development, employee relations, rewards and recognition, performance management, and health and safety.

Rooms Division

Front office.

Reporting to the director of rooms, the front office manager, sometimes called the reception manager, controls the availability of rooms and the day-to-day functions of the front office. The front desk agent reports to the front office manager and works in the lobby or reception area to welcome the guests to the property, process arrivals and departures, coordinate room assignments and pre-arrivals, and respond to guest requests.

Housekeeping

Reporting to the director of rooms, the executive housekeeper manages and oversees housekeeping operations and staff including the housekeeping manager, supervisor, house persons, and room attendants. An executive housekeeper is responsible for implementing the operating procedures and standards. He or she also plans, coordinates, and schedules the housekeeping staff. Room audits and inspections are completed regularly to ensure standards are met (go2HR, 2015b).

Reporting to the housekeeping supervisor, room attendants complete the day-to-day task of cleaning rooms based on standard operating procedures and respond to guest requests. Reporting to the housekeeping supervisor, house persons clean public areas including hallways, the lobby, and public restrooms, and deliver laundry and linens to guest rooms.

Reservations

Large full-service hotels typically have a reservations department, and the reservations manager reports directly to the front office manager. The guest’s experience starts with the first interaction a guest has with a property, often during the reservation process. Reservations agents convert calls to sales by offering the guest the opportunity to not only make a room reservation but also book other amenities and activities.

Today, with online and website reservations available to guests, there is still a role for the reservations agent, as some guests prefer the one-to-one connection with another person. The extent to which the reservations agent position is resourced will vary depending on the hotel’s target market and business strategy.

Sales and Marketing

The sales and marketing director is responsible for establishing sales and marketing activities that maximize the hotel’s revenues. This is typically accomplished by increasing occupancy and revenue opportunities for the hotel’s accommodation, conference and catering space, leisure facilities, and food and beverage outlets. The sales and marketing manager is responsible for coordinating marketing and promotional activities and works closely with other hotel departments to ensure customers are satisfied with all aspects of their experience (go2HR, 2015c).

Catering and Conference Services

In larger full-service hotels with conference space, a hotel will have a dedicated catering and conference services department. The director of this department typically reports to the director of sales and marketing. The catering and conference services department coordinates all events held in the hotel or catered off-site. Catering and conference events and services range from small business meetings to high-profile conferences and weddings.

Now that we have a sense of the building blocks of a typical hotel operation, let’s look at some trends affecting the sector.

Trends and Issues

The accommodation sector is sensitive to shifting local, regional, and global economic, social, and political conditions. Businesses must be flexible to meet the needs of their different markets and evolving trends. These trends affect all hotel types, regions, and destinations differently. However, overall, hoteliers must respond to these trends in a business landscape that is increasingly competitive, particularly in markets where the supply base is growing faster than demand ( Hotelier , 2014).

The Sharing Economy: Airbnb

The sharing economy is a relatively new economic model in which people rent beds, cars, boats, and other underutilized assets directly from each other, all coordinated via the internet ( The Economist , 2013). Airbnb is the most prominent example of this model. It provides a platform for travellers and manages all aspects of the relationship without requiring any paperwork.

At Airbnb, the host who rents out the space controls the price, the description of the space, and the guest experience. The host also makes the house rules and has full control over who books the space. As well, both hosts and guests can rate each other and write reviews on the website (Cole, 2014).

Airbnb began in 2008 when the founders rented their air mattresses to three visitors in San Francisco (Fast Company, 2012). In fact, the name Airbnb is derived from “air mattress bed and breakfast.” However, Airbnb is not only for couch surfers or budget-conscious travellers; it includes a wide range of spaces in locations all over the world. When users create an account, they set the price and write the descriptions to advertise the space to guests (Airbnb, 2015). Since 2008, the Airbnb online marketplace has grown rapidly, with more than 1 million properties worldwide and 30 million guests who used the service by the end of 2014 (Melloy, 2015).

This and other innovations have changed the accommodation landscape as never before. Ten to 15 years ago online travel agents were a major innovation that changed the distribution and sale of rooms. But they still had to work with existing hotels, whereas Airbnb has enabled new entrants into the industry and thus increased supply.

On the supply side, Airbnb enables individuals to share their spare space for rent; on the demand side, consumers using Airbnb benefit from increased competition and more choice. An unanswered question is to what extent Airbnb has impacted the hospitality industry at large and how it will impact it in the future. A study completed in 2014 in Austin, Texas, indicates that lower-end hotels, and hotels not catering to business travellers, are more vulnerable to increased competition from rentals enabled by firms like Airbnb than are hotels without these characteristics (Zervas, Preserpio, & Byers, 2015).

Distribution and Online Travel Agents

Online travel agents (OTAs) are a valuable marketing and third-party distribution resource for hotels and play a significant role in online distribution (Inversini & Masiero, 2014). In the first quarter of 2014, 13.2% of hotel bookings for individual leisure and business travellers (TravelClick, 2014) were made through OTAs (for example, Expedia, Hotels.com, Kayak.com).

OTAs offer global distribution so that each hotel and chain can be available to anyone at the click of a button (Then Hospitality, 2014). Smaller independent hotels that do not have the global marketing and sales resources of a larger chain are able to gain exposure, sell rooms, and build their reputation through online guest ratings and reviews. OTAs also help hotels offer combined value and packaging options that are attractive to many consumers (for example, booking and search options for hotels, car rentals, air fare, attractions, and travel packages). Customized searches, travel guidance, and rewards points are also available when booking through an OTA. If a hotel or chain has an exceptional product and service, OTAs share guest ratings, which can increase the number of reservations and referrals.

Chris Anderson at the Center for Hospitality Research at Cornell University analyzed 1,720 reservations made on the websites of six InterContinental Hotels brands (2012). Anderson found that every booking made on Expedia attracted three to nine reservations to the hotel’s site, suggesting the commission a hotel pays an OTA is a cost-effective expense, as it generates additional revenues.

The general industry guidance for hotels using OTAs is to ensure that this distribution channel is part of a broader sales strategy, coupled with sound customer relationship management practices.

Table 3.4 provides an overview of some of the distribution channels that are available to hoteliers.

For more on marketing in the services sector, see Chapter 8.

Online Bookings and Mobile Devices

In 2014, 27% of online bookings in leading regions in the United States were made by consumers using their mobile devices and tablets (Travel Click, 2014). As the trend continues, hoteliers are adapting their e-commerce strategy to respond appropriately and to understand what consumers in their hotel segment need, want, and expect from the mobile booking experience. According to Travel Click (2014), same-day reservations are also on the rise. Bookings made with mobile devices can be incentivized by offers for deals such as mobile-specific rate plans or discounts to directly target last-minute shoppers.

Table 3.5 was generated by a review of press releases (Hotel Analyst, 2014), and it provides some examples of mobile technologies and customized apps used by hotel companies.

The accommodation sector, and the hotel sector in particular, encompasses multiple business models and employs hundreds of thousands of Canadians. A smaller, but important segment in BC is that of camping and RV accommodators.

As broader societal trends continue and morph, they will continue to impact the accommodations marketplace and consumer. Owners and operators must stay abreast of these trends, continually altering their business models and services to remain relevant and competitive.

Now that we have a better sense of the accommodation sector, let’s visit the other half of the hospitality industry: food and beverage services. Chapter 4 explores this in more detail.

- Average daily rate (ADR): average guest room income per occupied room in a given time period

- BC Hospitality Foundation (BCHF): created to help support hospitality professionals in their time of need; now also a provider of scholarships for students in hospitality management and culinary programs

- BC Hotel Association (BCHA): the trade association for BC’s hotel industry, which hosts an annual industry trade show and seminar series, and publishes InnFocus magazine for professionals

- BC Lodging and Campgrounds Association (BCLCA): represents the interests of independently owned campgrounds and lodges in BC

- Camping and RVing British Columbia Coalition (CRVBCC): represents campground managers and brings together additional stakeholders including the Recreation Vehicle Dealers Association of BC and the Freshwater Fisheries Society

- Competitive set: a marketing term used to identify a group of hotels that include all competitors that a hotel’s guests are likely to consider as an alternative (minimum of three)

- Costs per occupied room (CPOR): all the costs associated with making a room ready for a guest (linens, cleaning costs, guest amenities)

- Fractional ownership: a financing model that developers use to finance hotel builds by selling units in one-eighth to one-quarter shares

- Franchise: enables individuals or investment companies to build or purchase a hotel and then buy or lease a brand name under which to operate; also can include reservation systems and marketing tools

- Franchisee: an individual or company buying or leasing a franchise

- Franchisor: a company that sells franchises

- Hotel Association of Canada (HAC): the national trade organization advocating on behalf of over 8,500 hotels

- Hotel type: a classification determined primarily by the size and location of the building structure, and then by the function, target markets, service level, other amenities, and industry standards

- Motel: a term popular in the last century, combining the words “motor hotel”; typically designed to provide ample parking and easy access to rooms from the parking lot

- Occupancy: the percentage of all guest rooms in the hotel that are occupied at a given time

- Revenue per available room (RevPAR): a calculation that combines both occupancy and ADR in one metric

- Sharing economy: an internet-based economic system in which consumers share their resources, typically with people they don’t know, and typically in exchange for money

- SMERF: an acronym for the social, military, educational, religious, and fraternal segment of the group travel market

- On a piece of paper, list as many types of accommodation classifications (e.g., by size) as you can think of. Name at least five. Provide examples of each.

- When researching a franchisor, the cost of the franchise must be carefully considered. What other factors would you consider to determine the value of a franchise fee?

- How should lower-end hotels and hotels that do not cater to business travellers respond to increased competition from rentals enabled by firms like Airbnb?

- A hotel earns $3,000 on 112 rooms. What is its ADR?

- That same hotel has an occupancy of 75%. What is its RevPAR?

- How many independent campgrounds are there across Canada?

- How many vehicle-accessible campsites are there in BC?

- Airbnb enables hosts to rate their guests after a stay. Consider some other types of accommodation and list the pros and cons of rating guests.

- Draw an organizational chart for a 60-room boutique hotel, listing all the staff required to run the operation. Put the most influential people (e.g., the general manager) at the top and work your way down. How would you structure this differently from a larger full-service hotel? What would you keep the same?

- Read the Condé Nast list for Best Hotels and Resorts in Canada for 2014 (in the Take a Closer Look feature). Now find two other “best of” lists for BC, Canada, or global accommodations. What do the winners have in common? List at least three things. Now try to find at least two differences.

Case Study: Hotel for Dogs – Philanthropy and Media Coverage

In 2014, the media was taken by storm with a story about a hotel in North Carolina that combined philanthropy with their business model. The property expanded on the trend of allowing dogs in hotels by fostering rescues from a nearby shelter and allowing guests to adopt them. Guests appreciated the warm interactions with the animals and several dogs were adopted as a result (Manning, 2014).Not only did the property provide a valuable service and enhance the guest experience, but the story was repeated across multiple media outlets, creating publicity for the hotel.

This is an example of a current trend: allowing pets in hotels. Now choose from one of the following trends, and research it to answer the questions that follow:

- Carbon offset programs

- Customization

- Reputation management

- Digital concierge

- Themed sleep

- Lifestyle food choices

- Educational experiences

- Millennial traveller

- Sharing economy

- Green certified

- Extreme experiences

- Why do you think this trend has emerged? What market is it helping to serve?

- Find an example of a hotel that has responded to your chosen trend and explain how the trend has informed or changed the hotel’s business strategy or practice.

- Are there any trends that are not listed above that you think should be added? Try to name at least two. Why are these important accommodation trends today?

Accor. (2015). Brand portfolio, economy brands . Retrieved from www.accor.com/en/brands/brand-portfolio.html

Airbnb. (2015). How to host . Retrieved from www.airbnb.ca/help/getting-started/how-to-host

Anderson, C. (2012, November). The impact of social media on lodging performance . Retrieved from www.hotelschool.cornell.edu/research/chr/pubs/reports/abstract-16421.html

Boutique Hotel Association. (n.d.) Terminology and definitions for boutique and lifestyle hotels and properties. Retrieved from www.blla.org/lifestyle-hotels.htm

Brey, E. (2009). Resort definitions and classifications: A summary report to research participants. [PDF] University of Memphis: Center for Resort and Hospitality Business. Retrieved from http://caribbeanhotelassociation.com/source/Members/DataCenter/Research-UofMemphis.pdf

Cabañas, A. (2014). “Chain” versus “independent” – A view from an operator of independent hotels. hospitalitynet . Retrieved from www.hospitalitynet.org/news/4064293.html

Canada History. (2013). The railroad. Retrieved from www.canadahistory.com/sections/eras/nation%20building/Railroad.html

CNW. (2014, May 1). Canadian RV and camping industry urges government to address critical infrastructure needs. Retrieved from www.newswire.ca/en/story/1347701/canadian-rv-and-camping-industry-urges-government-to-address-critical-infrastructure-needs

Coast Hotels and Resorts. (2015) Management and franchises . Retrieved from www.maclabhotels.com/about_coast/management

Cole, S. (2014). Fast company how a startup grows up: Lessons from AirBnB’s open air summit . Retrieved from www.fastcompany.com/3029758/how-a-startup-grows-up-lessons-from-airbnbs-openair-summit

Crandell, C., Dickinson, K., & Kanter, G. I. (2004). Negotiating the hotel management contract. In Hotel Asset Management: Principles & Practices. East Lansing, MI: University of Denver and American Hotel & Lodging Educational Institute.

CRVBCC. (2014). About us: The Camping and RVing British Columbia Coalition . Retrieved from www.campingrvbc.com/about/

Diffen. (2015). Hotel vs motel. Retrieved from www.diffen.com/difference/Hotel_vs_Motel

Economist, The. (2013). Silverstein, B. The rise of the sharing economy. Retrieved from www.economist.com/news/leaders/21573104-internet-everything-hire-rise-sharing-economy

Fairmont Hotels and Resorts. (2015). Chief engineer job description . Retrieved from www.linkedin.com/company/fairmont-hotels-and-resorts?trk=job_view_topcard_company_name

Fast Company. (2012). Airbnb – Most innovative companies 2012 . Retrieved from www.fastcompany.com/3017358/most-innovative-companies-2012/19airbnb

go2HR. (2015a). Accommodations . Retrieved from www.go2hr.ca/bc-tourism-industry/what-tourism/accommodation

go2HR. (2015b). Executive housekeeper profile . Retrieved from www.go2hr.ca/career-profiles/executive-housekeeper

go2HR. (2015c). Director of sales and marketing in hotel profile . Retrieved from www.go2hr.ca/career-profiles/director-sales-and-marketing-hotel

Hotel Analyst. (2014). The intelligence source for the hotel investment community . Retrieved from http://hotelanalyst.co.uk

Hotel Association of Canada. (2014). Hotel industry fact sheet . [PDF] Retrieved from www.hotelassociation.ca/forms/Hotel%20Industry%20Facts%20Sheet.pdf

Hotelier. (2014, September 12). The 2014 hospitality market Report. Retrieved from www.hoteliermagazine.com/the-2014-hospitality-market-report/

Inversini, A., Masiero, L. (2014). Selling rooms online: the use of social media and online travel agents. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 26 (2), 272-292

McDonald, B. (2011). Canadian Monthly Lodging Outlook . Retrieved from www.hvs.com/Library/Articles/

Manning, S. (2014, December 31). This hotel is saving lives by matching guests with rescue pups. Huffington Post . Retrieved from www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/12/31/hotel-rescue-dogs_n_6401418.html

Meiszner, P. (2014, June 27.) Fairmont Empress hotel in Victoria purchased by Vancouver developer. Global News. Retrieved from http://globalnews.ca/news/1421407/fairmont-empress-hotel-in-victoria-purchased-by-vancouver-developer/

Melloy, J. (2015, February 2). Airbnb guests triple hurting Priceline, HomeAway. CNBC. Retrieved from www.cnbc.com/id/102389442

Migdal, N. (n.d.) Franchise agreements vs. management agreements: Which one do I choose? Hotel Business Review . Retrieved from hotelexecutive.com/business_review/2101/test-franchise-agreements-vs-management-agreements-which-one-do-i-choose

Rushmore, S. (2005). What does a hotel franchise cost? Canadian Lodging Outlook . Retrieved from www.hotel-online.com/News/PR2005_4th/Oct05_FranchiseCost.html

SilverBirch Hotels. (2015). About us . Retrieved from www.silverbirchhotels.com/about/

Starwood Hotels. (2011, April 12). Starwood to reach 60th hotel milestone in Canada . Retrieved from www.starwoodhotels.com/sheraton/about/news/news_release_detail.html?Id=2011-04-12-SI&language=en_US

Then Hospitality. (2014, April 15). The benefits of using online travel agencies (OTAs) . Retrieved from www.thenhospitality.com/blog/the-benefits-of-using-online-travel-agencies-otas

Travel Click. (2014). Business and leisure travelers continue to book more hotel reservations online . Retrieved from www.travelclick.com/en/news-events/press-releases/business-and-leisure-travelers-continue-book-more-hotel-reservations-online

Wedgewood Hotel & Spa. (2014). Luxury boutique Vancouver Hotel – Wedgewood Hotel & Spa . Retrieved from www.wedgewoodhotel.com

Western Investor. (2012). Investors burnt in hotel condos, fractionals . Retrieved from westerninvestor.com/index.php/news/ab/692-investors-burnt-in-hotel-condos-fractionals

Zervas, G., Preserpio, D., & Byers, J.W., (2015). The rise of the sharing economy: Estimating the impact of Airbnb on the hotel industry . Boston U. School of Management Research Paper No. 2013-16. Available at SSRN: ssrn.com/abstract=2366898 or dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2366898

Attributions

Figure 3.1 Shot from balconey by Alan Wolf is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 license.

Figure 3.2 Banff Springs Hotel by Evan Leeson is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 3.3 JONETSUpanpac07 by Jonetsu.ca is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 3.4 The Magnolia Hotel (Victoria) 2013 by Raul Pacheco-Vega is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 3.5 Wedgewood Hotel by Stewart Marshall is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 3.6 The Empress by 3dpete is used under a CC BY ND 2.0 license.

Figure 3.7 Coast Bastion Hotel (Nanaimo) by Raul Pacheco-Vega is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 3.8 Delta Sun Peaks Hotel by jhopkins is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 3.9 Hotel Georgia, Rosewood Hotel Vancouver by Rishad Daroowala is used under a CC BY-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 3.10 Night Neighbours by James Wheeler is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 3.11 Vicky Lee at Delta Burnaby Hotel by LinkBC is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 3.12 Scott and Tina Visit the Pan Pacific Vancouver by Pan Pacific Hotel is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 3.13 Cafe Pacifica Restaurant 2013 Winter Menus by Pan Pacific is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 3.14 Airbnb by Gustavo da Cunha Pimenta is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 3.15 Waiting at baggage claim by hjl is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 license.

Introduction to Tourism and Hospitality in BC Copyright © 2015 by Rebecca Wilson-Mah is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of amenity in English

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

- consumer society

- culturomics

- digital divide

- non-segregated

- non-segregation

- non-utility

- sociologist

- superstructure

- uncivilized

amenity | American Dictionary

Amenity | business english, examples of amenity, translations of amenity.

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

injury to someone caused by severe cold, usually to their toes, fingers, ears, or nose, that causes permanent loss of tissue

Keeping up appearances (Talking about how things seem)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- basic amenities

- American Noun

- Translations

- All translations

To add amenity to a word list please sign up or log in.

Add amenity to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

Home » Language » English Language » Words and Meanings » Difference Between Amenities and Facilities

Difference Between Amenities and Facilities

The main difference between amenities and facilities is that the amenities refer to things that are designed to provide comfort and enjoyment to the guests while facilities basically refer to places or even equipment built to facilitate guests in their specific needs.

These two terms are common in the hotel and hospitality terminologies, and often, people tend to use them interchangeably. However, they have different meanings that pertain to their correct usage.

Key Areas Covered

1. What are Amenities – Definition, Features, Examples 2. What are Facilities – Definition, Features, Examples 3. What is the Difference Between Amenities and Facilities – Comparison of Key Differences

What are Amenities

Amenities are not buildings or construction. They are the things or benefits that are made to offer convenience and comfort to people. In other words, they are things that conduce comfort, convenience or enjoyment of the people.

Amenities are additional features or comfort things inside a property or building, and they add extra value to it. Moreover, amenities are usually the benefits that come with the hotel services or with an apartment . They render the pleasure and comfort to the guests. Therefore, the more amenities a building has, the more likely it will gain a competitive edge in attracting prospective tenants and guests.

Figure 1: Amenities in a Hotel

Amenities in a hotel may include things or services such as high kitchen quality services, valet services, quality products, WIFI, elevators, air conditioning, TV and computers for use, balconies, laundry services, swimming pool, playground, etc.

What are Facilities

Facilities are places (as a hospital, machinery, plumbing) that are built, constructed, installed, or established to perform some particular function, and thus to facilitate people in that.

In brief, a facility can be a building designed for a particular purpose. But, this purpose may not always be enjoyment; it is often for other needs as well. They can range from providing healthcare, monitoring the security of the place, developing technological advancements, and providing relaxation and comfort to people too

With concern to hotel and tourism industry, facilities are also places that are constructed to answer the particular needs of the guests. Therefore, unlike amenities, their main aim is not to provide pleasure and entertainment but to render a specific service and facilitate the people in the process of it.

Figure 2: Spa in a Hotel

Some public facilities include medical facilities, telecommunication facilities, educational facilities, research facilities, and commercial or institutional buildings, such as a hotel, resort, school, office complex, sports arena, or convention center etc.

Some examples of hotel facilities are health clubs, spas, conference facilities, banquet halls, movie theatres, parking areas, etc.

Since the hotel industry mainly aims at providing the best services to the guests, the amenities they provide often get categorized under hotel facilities.

Amenities refer to things that are designed to provide comfort and enjoyment to the guests while the facilities mainly refer to places or even equipment built to facilitate guests in their specific needs.

The main aim of the amenities is to provide comfort, pleasure and enjoyment for people while the main aim of the facilities is to facilitate the people in their necessities. Therefore, they answer particular needs, but people staying there may or may not enjoy them.

The word, ‘amenity’ is thus used mostly in the hotel and other related industries while the word ‘facility’ can be used mostly in a general sense in addition to its use in the hotel and tourism industry.

Examples in Hotel Industry

Some examples of hotel amenities are swimming pools, games, high-quality products such as dishwasher units, microwave ovens, washer and dryers, minibars, shampoos, laundry services, internet and computer services, balconies, transport services, swimming pool, childcare centre, playground, etc

Some examples of hotel facilities are gyms, spas, community service centres, tourist aid centres, childcare centres, business service centres, etc. However, in the tourism industry, the main aim of the facilities is also to provide the best services to make the guest feel more at ease and comfortable.

The two terms amenities and facilities are commonly used to express benefits and places that provide facilities for people. Thus, these two words are common in the hotel and tourism terminology. The difference between amenities and facilities is that the amenities refer to things provided mainly for the enjoyment and comfort of the guests while facilities are the places that are constructed for a particular purpose thus, facilitating the guests in their needs.

1. “Hotel Amenity.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 19 June 2018, Available here . 2. “Facility.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 29 May 2018, Available here .

Image Courtesy:

1. “L’HOTEL PORTO BAY SÃO PAULO | amenities” by PortoBay Hotels & Resorts (CC BY 2.0) via Flickr 2. “Spa at Mandarin Oriental Harmony Suite Tokyo” By Mandarin Oriental Hotel Group – Mandarin Oriental Hotel Group (CC BY-SA 3.0) via Commons Wikimedia

About the Author: Upen

Upen, BA (Honours) in Languages and Linguistics, has academic experiences and knowledge on international relations and politics. Her academic interests are English language, European and Oriental Languages, Internal Affairs and International Politics, and Psychology.

You May Also Like These

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Definition of 'amenities'

Amenities in british english.

amenities in American English

Amenities in hospitality, examples of 'amenities' in a sentence amenities, cobuild collocations amenities, trends of amenities.

View usage for: All Years Last 10 years Last 50 years Last 100 years Last 300 years

Browse alphabetically amenities

- Amenhotep III

- Amenhotep IV

- amenity bed

- amenity society

- All ENGLISH words that begin with 'A'

Related terms of amenities

- basic amenities

- hotel amenities

- luxury amenities

- public amenities

- View more related words

Quick word challenge

Quiz Review

Score: 0 / 5

Wordle Helper

Scrabble Tools

UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

Ethics, culture and social responsibility.

- Global Code of Ethics for Tourism

Accessible Tourism

- Tourism and Culture

- Women’s Empowerment and Tourism

share this content

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2023), 1.3 billion people - about 16% of the global population - experience significant disability. Accessibility for all to tourism facilities, products, and services should be a central part of any responsible and sustainable tourism policy. Accessibility is not only about human rights. It is a business opportunity for destinations and companies to embrace all visitors and enhance their revenues.

Did you know..?

- Almost 50% of people aged more than 60 have a disability (UNDESA, 2022)

- Travellers with disabilities tend to travel accompanied by 2 to 3 travel companions (Bowtell, 2015)

- 2/3 of people with disabilities in developed economies are likely to have means to travel (based on Bowtell, 2015)

This portal provides an insight into UN Tourism resources on accessibility. All resources were developed with key inputs from Organizations with Persons with Disabilities (OPDs), civil society and tourism sector stakeholders. The publications generally follow the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 (level AA).

International Accessible Tourism Forum - Asia & the Pacific

Download here the Programme of the Forum .

UN Tourism International Conference on Accessible Tourism

The Conference discussed accessible tourism policies and product development, as well as international guidance tools applied to the tourism value chain. Good practices showcased innovative solutions in access to transportation, cultural heritage, nature areas, leisure, MICE and a wide range of tourism businesses. The UN Tourism & San Marino Action Agenda for the Future of Accessible Tourism 2030 outlines a series of public commitments to undertake specific accessibility improvements.

Download here the Programme of the Conference .

Download the San Marino Action Agenda in English , Spanish , French and Arabic .

Recommendations for managers of natural resources

A set of guidelines on accessibility targeting key players in the management of natural resources, was published by UN Tourism in October 2023. The document focuses on facilitating access to protected nature areas, beaches and parks. The WCPA Tourism and Protected Areas Specialist Group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and the European Network for Accessible Tourism (ENAT) , acted as the expert reviewers. Their involvement was key in identifying the best actions geared towards a greater extent of accessibility and inclusiveness within nature areas, vis a vis tourism.

The guidance tool, whose drafting was led by UN Tourism, the ONCE Foundation and UNE, is part of the promotion of ISO Standard 21902:2021 .

Download here the guidelines in English and Spanish .

Recommendations for cultural tourism key players

Download here the English and Spanish version of the Recommendations.

Recommendations for Accommodation, Food&Beverage and MICE companies

Download the user-guide (January 2023) here:

Recommendations for governments and destinations

Download the user-guide (December 2022) produced in collaboration with Turismo de Portugal, Turismo Argentina and European Network for Accessible Tourism (ENAT):

Accessibility Standards guiding the Recovery

You can click and download below the takeaway thoughts & conclusions (accessible PDF file) : ➥ Conclusions (in accessible PDF format) - English: Webinar ➥ Conclusions (in accessible PDF format) - Spanish: Webinar

UN Tourism Inclusive Recovery Guide - Persons with Disabilities

- Download full document

Reopening Tourism for Travellers with Disabilities

Accessible Tourism Destination

The ATD is an annual UN Tourism distinction based on an Expert Committee evaluation, which acknowledges destinations enabling a seamless experience to any tourist, regardless of their abilities . The first ATD was awarded in 2019 and has been temporarily put on hold.

Documents available for download:

- Expert Committee

- Accessible Tourism Destination award (First Edition)

Video "Change your destination"

The video “Change your destination” was issued by Fundación ONCE and UN Tourism by the occasion of the 2019 International Fair of Tourism (FITUR).

Facilitating travel for people with disabilities is an exceptional business opportunity. Yet, a change in mind-set and in the model of tourism services provision is needed in order to meet this major market demand. Accessible environments and services contribute to improve the quality of the tourism product and can create more job opportunities for people with disabilities.

Accessibility, therefore, must be an intrinsic part of any responsible and sustainable tourism policy and strategy.

World Tourism Day 2016: "Tourism for All - promoting universal accessibility"

While these examples provide a small sample of possible solutions regarding accessibility, they will hopefully inspire others to take steps towards broadening the availability of accessible offers in tourism destinations around the world.

Download full text: Tourism for All - promoting universal accessibility

UN Tourism Recommendations on Accessible Information in Tourism

Ensuring that the information is accessible, is without any doubt a key to communicating successfully with visitors in all stages of their journey, particularly with regards to travelers with disabilities and special access requirements.

The UNWTO Recommendations on Accessible Information in Tourism have been developed with the support and collaboration of the ONCE Foundation for Cooperation and Social Inclusion of People with Disabilities and the European Network for Accessible Tourism (ENAT). They were adopted by the Resolution A/RES/669(XXI) of the General Assembly of UNWTO as a follow-up to the ‘Recommendations on Accessible Tourism for All’ of 2013.

Download full text: UNWTO Recommendations on Accessible Information in Tourism

UN Tourism Recommendations on Accessible Tourism for All

The Recommendations incorporate the most relevant aspects of the UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities of 2006 and the principles of Universal Design.

In the context of a trilateral agreement between UNWTO, ONCE and ENAT, the recommendations were adopted by UNWTO General Assembly Resolution A/RES/637(XX) of August 2013, updating the 2005 UNWTO Recommendations.

Download full text: UNWTO Recommendations on Accessible Tourism for All

San Marino Declaration on Accessible Tourism

The Declaration which resulted from the 1st UNWTO Conference on Accessible Tourism in Europe, held on 19-20 November 2014 in the Republic of San Marino, can be downloaded here:

Download full text: Highlights of the 1st UNWTO Conference on Accessible Tourism in Europe

Highlights of the 1st UN Tourism Conference on Accessible Tourism in Europe

In recognition of accessibility’s importance in the tourism sector, UNWTO and the Government of San Marino jointly organized the 1st UNWTO Conference on Accessible Tourism in Europe (19 - 20 November 2014).

Drawing together policy makers, tourism destinations, the private sector and civil society, this landmark event addressed challenges in advancing quality, sustainability and competitiveness within the tourism sector through universal accessibility.

This publication features 14 good practices presented at the Conference which focus on accessibility of cultural heritage sites, policy frameworks and strategic actions to make accessible tourism a reality.

Manuals on Accessible Tourism for All

One of the most significant outcomes of a major collaboration framework between UN Tourism and Disabled People’s Organizations (DPOs), particularly the Spanish ONCE Foundation for the Cooperation and Social Inclusion of People with Disabilities, the European Network for Accessible Tourism (ENAT) , and the Spanish ACS Foundation , are the Manuals on Accessible Tourism for All.

The manuals are meant to assist tourism stakeholders in improving the accessibility of tourism destinations, facilities and services worldwide.

Manual on Accessible Tourism for All: Public-Private Partnerships and Good Practices

Download full text: English | Spanish

Download Executive Summary: English | Français

Module I: Definition and Context

Download full text: Module I: Definition and Context

Module II: Accessibility Chain and Recommendations

Download full text: Module II: Accessibility Chain and Recommendations (Español)

Module III: Principal Intervention Areas

Download full text: Module III: Principal Intervention Areas (Español)

Module IV: Indicators for Assessing Accessibility in Tourism

Module IV of the Manual on Accessible Tourism for All: Principles, Tools and Best Practices , co-produced with the ONCE Foundation and ENAT, proposes a series of indicators developed for tourism destinations to assess, control, and manage their accessible tourism offer. Accompanied by a detailed methodology for their application, these indicators can serve as a practical tool not only to assess the current situation within destinations but also to consider further actions that may be required. Module IV is currently available in Spanish only, in a digital accessible version.