No products in the basket.

Nottingham Prison Information

- Accommodation: The prison provides multiple residential units with individual cells or shared accommodation for inmates. The cells are equipped with basic amenities, including beds, personal storage, and sanitation facilities.

- Education and Vocational Training: Nottingham Prison offers a range of educational programs and vocational training opportunities to help inmates develop skills, improve their prospects, and prepare for their eventual release. These programs may include basic education, literacy and numeracy courses, vocational skills training, and accredited qualifications.

- Work Opportunities: Inmates have access to work opportunities within the prison, such as maintenance, cleaning, kitchen, and other designated roles. These work activities aim to develop skills, instill discipline, and provide a sense of responsibility.

- Healthcare: Nottingham Prison has an on-site healthcare unit staffed with medical professionals who provide primary healthcare services to prisoners. Mental health support, substance abuse programs, and specialized medical care are also available.

- Family Contact: The prison recognizes the importance of maintaining family relationships and facilitates visits and contact with family members, subject to specific guidelines and regulations.

- Resettlement Support: Nottingham Prison offers pre-release planning and support to help inmates prepare for their eventual release. This may include assistance with accommodation, employment, and access to community-based support services.

Contact Information

Booking a visit to nottingham prison.

- Monday: 1pm to 4pm

- Tuesday: 9am to 12pm

- Wednesday: closed

- Thursday: 1pm to 4pm

- Friday: closed

- Saturday: 9am to 12pm

- Sunday: closed

Unlimited Prison Phone Calls Package

- Monday: 9am to 10:30am and 2pm to 3:30pm

- Tuesday: 9am to 10:30am and 2pm to 3:30pm

- Wednesday: 9am to 10:30am and 2pm to 3:30pm

- Thursday: 9am to 10:30am and 2pm to 3:30pm

- Saturday: 9am to 10:30am and 2pm to 3:30pm

- Sunday: 9am to 10:30am and 2pm to 3:30pm

- Valid Passport

- Valid Photographic

- Driving Licence (full or provisional)

- Citizen Card

- Senior Citizens Bus Pass Travel Card (issued by Scottish Government)

- Utility bill

- Council tax bill

- Benefit book

- Bank statement

- other letter from official source

- Skip to Navigation

- Skip to Content

Langue du site

Visiting the prison

Maintaining contact with family members or close friends is an important part of the rehabilitation process and helps to support our prisoners during their sentence. Our large, open-plan visits halls provide a relaxed atmosphere for both prisoners and their visitors. With refreshments available to purchase and play areas for younger children, we want to make your visiting experience as comfortable and enjoyable as possible.

We understand that visiting a prison can be quite daunting, especially if it is your first visit, so we try to make your experience as positive as possible. We want you to enjoy your visit, so we operate a zero tolerance for violence and aggressive behaviour to help us maintain a calm, friendly environment.

Children under the age of 18 must be accompanied by an adult.

Prohibited items

Please note the following items are not permitted inside the prison:

- Controlled / Illegal Drugs

- Metal Cutlery

- Chewing Gum

- Mobile devices

Please take the time to read and familiarise yourself with the list. View the prohibited items list .

We provide lockers for you to store personal belongings such as wallets, mobile phones and tobacco.

Professional / Legal visits

These will be available Monday to Friday between the times of 0900 - 1130hrs and 1430 - 1700hrs.

To book a legal visit, please contact: [email protected]

A confirmation will be emailed as soon as possible.

Parental Consent Form

Please download and complete the Parental Consent Form before your visit.

Visiting times and frequency

Details about visiting times allowed at HMP Lowdham Grange

Learn more Close

At HMP Lowdham Grange we believe in the importance of maintaining a healthy relationship with family and friends. We place a great deal of importance in making your visit experience as good as it possibly can be.

Visiting times

All social visits can only be booked by the prisoners themselves via internal processes.

Monday - In the morning from 0900 to 1000hrs and then 1030 to 1130hrs. In the afternoon, from 1430 to 1530hrs and 1600 to 1700hrs.

Tuesday - In the morning from 0900 to 1000hrs and then 1030 to 1130hrs. In the afternoon, from 1430 to 1530hrs and 1600 to 1700hrs.

Wednesday - In the morning from 0900 to 1000hrs and then 1030 to 1130hrs. In the afternoon, from 1430 to 1530hrs and 1600 to 1700hrs.

Thursday - In the morning from 0900 to 1000hrs and then 1030 to 1130hrs. In the afternoon, from 1430 to 1530hrs and 1600 to 1700hrs.

Friday - In the morning from 0900 to 1000hrs and then 1030 to 1130hrs. In the afternoon, from 1430 to 1530hrs and 1600 to 1700hrs.

Saturday - In the morning from 0900 to 1000hrs and 1030 to 1130hrs. In the afternoon from 1430 to 1530hrs and then 1600 to 1700hrs.

Sunday - In the morning from 0900 to 1000hrs and 1030 to 1130hrs. In the afternoon from 1430 to 1530hrs and then 1600 to 1700hrs.

Can money be taken in for a prisoner?

Visitors cannot give money to a prisoner during visits, but they can send money to a prisoner’s account :

- Send money free by debit card, you will need the prisoner number and their date of birth. Go to www.gov.uk/send-prisoner-money (opens in a new window).

- As a cheque (subject to 10 working days for clearance)

- As a postal order

What to expect

Guidelines of what to expect when visiting HMP Lowdham Grange

All first-time visitors must bring some form of photographic identification and a proof of address in order for them to be processed on to the system.

The following are examples of what could be used as photo ID:

- Current Passport

- Driving Licence

- Senior Citizens transport pass, issued by local authority

- Employers or Student ID card (Only if this clearly shows the name of the visitor and the employer/educational establishment, has a photograph and signature that can be compared and if it is a recognised employer or educational establishment) .

If your visitor is bringing children with them, they must bring the birth certificate or Passport and if it is not the parent or guardian of the child they must also bring written consent from the parent or guardian of the child and the birth certificate or Passport.

Car parking

Visitors' parking is provided free of charge.

Visits policy

To maintain a suitable visiting environment and to comply with the security element within the hall visitors and prisoners are asked to follow the guidelines set out below.

- No items may be given to prisoners other than refreshments purchased in the hall.

- Prisoners and visitors will remain in their seats and not wander around the hall.

- All visitors will be searched and pass by the drug dog on entry to the establishment and if they leave the hall.

- Prisoners and visitors will not be abusive to staff, other prisoners, or other visitors.

- Children must be kept under control - including in the play area.

- Prisoners and visitors must not be unduly noisy.

- Prisoners may greet their visitors with a kiss and kiss them goodbye, this should be done in a manner that is not offensive to others, please note that there should be no other physical contact throughout the visit other than stated above.

- Prisoners and visitors must obey instructions from staff and leave quietly when instructed.

- Visitors may purchase refreshments from the tea bar for themselves and the prisoner; this is a table service option.

- Visitors may leave the hall to use the toilet providing staffing and other circumstances permit - The time spent will be part of the visit time allocated and level B searches will be carried out.

- Visits will be subject to CCTV surveillance and staff will patrol the hall.

- Visits by children to prisoners who have been identified as presenting a potential risk to children will be particularly closely monitored.

- Cash is permitted into the prison for use at the coffee shop to a maximum value of £15 per adult and £5 per child. Notes are not accepted, coins only.

Appropriate Clothing

All visitors must be appropriately dressed at all times. This is a family environment and we do not wish to offend people. The following restrictions apply to all visits:

- All skirts must be no more than 3 inches above the knee (no mini-skirts).

- Leggings must not be see through.

- No trousers or jeans with holes/rips/multiple zips or pockets around the groin area, and they must be pulled up around the waist.

- Trousers/jeans must not have holes in the pockets near to the groin area.

- No short or cropped tops revealing the midriff.

- No see-through tops or tops that show excessive cleavage.

- No camisole tops.

- Underwear must be worn at all times.

- Males in t-shirts must have a sleeve, vests are not acceptable.

- Clothing displaying offensive patterns or logos will not be permitted (i.e. Cannabis leaves, racist logos, gang tags or offensive words).

- No steel toe caps.

- Sunglasses, hats and scarves are not permitted (with the exception of headwear for religious reasons).

Failure to comply may result in the prisoner's visitor being refused entry.

Types of visit

Details about the social (friends and family) and legal visits at HMP Lowdham Grange

Social Visits

Social visits are booked by the prisoners using our Internal Pods system. Prisoners are shown how to use this on their induction (normally within the first 3 days). They need to register all their visitors’ details and then request a visit. This can take a few days. Unfortunately due to data protection we are unable to book any social visits for anyone calling in.

We have a kiosk in the Visits Hall where you can purchase hot drinks and snacks. Please be advised we can only accept payment via a credit card (cannot accept cash).

Social visits will be available every afternoon seven days a week and will be supplemented by visits in the morning at a weekend. The timings of these are shown below:

Day AM /PM

Monday 1430 – 1530 1600 - 1700

Tuesday 1430 – 1530 1600 – 1700

Wednesday 1430 – 1530 1600 – 1700

Thursday 1430 – 1530 1600 – 1700

Friday 1430 – 1530 1600 – 1700

Saturday 0900-1000 1030-1130 1430 -1530 1600-1700

Sunday 0900-1000 1030-1130 1430 -1530 1600-1700

On a Monday through to Friday, prisoners may, if they wish choose, to remain for the second session without exchanging a Visiting Order (VO) as demand is lower during a week day.

Amendments to Visits due to the New Core Day

If a prisoner wishes to book a two-hour visit at the weekend this will result in two VOs being used, one for each session from their entitlement. Due to the demand at the weekend one-hour slots are encouraged so that as many prisoners as possible have the opportunity to book a visit.

Two Hour sessions

Prisoners are advised that those who are using the entire/double session will still be subject to the break in between the two visits sessions in order to allow for the room to be tidied up etc. We will review this arrangement in the coming weeks so that there is less interruption to people’s visits.

Purple Visits

We are pleased to offer all prisoners access to the online app. Purple Visit, enabling video call visits with family and friend.

They are available at the following times:

Prisoners can book a session through the internal booking system (Pod). Please note that to participate in a Purple Visits session you must download the application to your mobile phone or tablet (not laptop) to enable booking to be confirmed. To download the app please visit https://www.purplevisits.com/ .

To book a legal visit please contact [email protected] . A confirmation will be emailed as soon as possible.

Video Link: to book a Video Link please email [email protected]

please note: these departments will not be able to give out any prisoner information

How we collect and use your data

COLLECTION OF DATA

In order to facilitate your visit to one of our prisons and to ensure that we deliver appropriate levels of security and safety and prevent crime, for identification purposes we shall collect your name, date of birth, address, a biometric template of your fingerprint and a photograph. A series of reference points from a finger print are collected, allowing a unique identification pattern. We do not collect or hold actual fingerprints.

Our prisons operate CCTV and staff may wear Body Worn Video Recording Equipment. We do not collect biometric readings or photographs of children under 16, however with the use of CCTV, images may routinely be captured.

DATA SHARING

We will only share your information with a third party where there is a legal obligation to do so.

RIGHTS OF ACCESS, CORRECTION, ERASURE AND RESTRICTION

You have legal rights in connection with personal information. Under certain circumstances, by law you have the right to:

- Request access to your personal information (commonly known as a “data subject access request”). This enables you to receive a copy of the personal information we hold about you and to check that we are lawfully processing it.

- Request correction of the personal information that we hold about you. This enables you to have any incomplete or inaccurate information we hold about you corrected.

- Request erasure of your personal information. This enables you to ask us to delete or remove personal information where there is no good reason for us continuing to process it. You also have the right to ask us to delete or remove your personal information where you have exercised your right to object to processing.

- Object to processing of your personal information by us or on our behalf in certain situations.

- Request the restriction of processing of your personal information. This enables you to ask us to suspend the processing of personal information about you, for example if you want us to establish its accuracy or the reason for processing it.

DATA RETENTION

We keep personal data in accordance with our clients’ and Sodexo’s retention procedures. These retention periods depend on the nature of the information (e.g. we apply different retention periods to different type of information such as CCTV and your visitor record), and may be subject to change.

If you have any questions or concerns about how long we retain your personal data, please contact the Data Protection Officer using the details below.

FURTHER ADVICE / GUIDANCE

To exercise your rights, you can contact us by writing to us at the following address: [email protected] or email the Global Data Protection Office at the following email address: [email protected] stating your surname, first name and the reason for your request. We will most likely ask you for additional information in order to identify you and to enable us to deal with your request

You also have the right to contact the Information Commissioner’s Office and file a complaint. ( https://ico.org.uk/concerns/ )

HMP Lowdham Grange

Old Epperstone Road Lowdham Nottingham NG14 7DA

Tel: 0115 966 9200

Latest News

Ways to stay in touch... .

- The weekly online and monthly printed national newspaper for prisoners and detainees

Search articles and comments

Hmp nottingham.

- Inside Time Reports

- 13th December 2014

- East Midlands , Male Local , Male YOI , Prison Visit

Prison information

Address: Perry Road Sherwood NG5 3AG Switchboard: 0115 872 4000 Managed by: HMPPS Region: East Midlands Category: Male local Link to: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/nottingham-prison

Description

Nottingham Prison is a men’s prison in the Sherwood area of Nottingham and serves courts in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire.

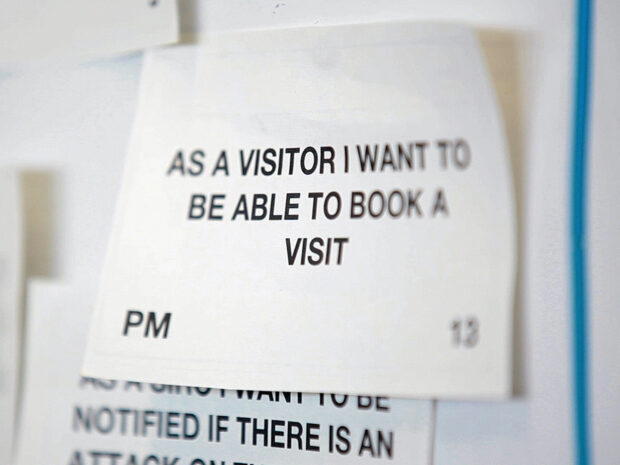

Visit Booking: On-line

Use this online service to book a social visit to a prisoner in England or Wales you need the:

- prisoner number

- prisoner’s date of birth

- dates of birth for all visitors coming with you

The prisoner must add you to their visitor list before you can book a visit.

You’ll get an email confirming your visit. It takes 1 to 3 days.

ID: Every visit Children’s Visits: General domestic visits allow children where no restrictions are in place for the individual. Bi monthly children’s visits have gathered pace so now delivering monthly with view for review for weekly.

Search reports

IMB Reports

Prison Inspectorates Reports

Probation Service Reports

Prisons and Probations Ombudsman

Search the InsideTime library

Related posts

Mailbites – april 2022, child abuse victims denied payouts due to convictions, world prison news, abuse suffered in foster care, prisons: the good, the bad and the ugly, revealed: jails with the most misconduct investigations, bright vibrant colours abound, life-changing minute, something missing or outdated.

If you have any information that you would like to be included or see anything that needs updating, contact Gary Bultitude at [email protected]

Share this on:

You might also enjoy...

- Prison Visit

- South Central

HMP WINCHESTER

One thought on “ hmp nottingham ”.

Thanks for every other informative website. Where else may I am getting that kind of information written in such a perfect means? I have a challenge that I am simply now running on, and I have been at the glance out for such info.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Conditions of acceptance of website comments

National Justice Museum

Top ways to experience National Justice Museum and nearby attractions

Most Recent: Reviews ordered by most recent publish date in descending order.

Detailed Reviews: Reviews ordered by recency and descriptiveness of user-identified themes such as waiting time, length of visit, general tips, and location information.

Also popular with travellers

NATIONAL JUSTICE MUSEUM: All You Need to Know BEFORE You Go (with Photos)

- Nottingham Quest: Self Guided City Walk & Immersive Treasure Hunt (From £29.45)

- Nottingham Treasure Hunt Adventure - Robin Hood's Secret Stash (From £7.63)

- Nottingham Walking Tour with a Local Guide (From £14.25)

- Fun and Flexible Treasure Hunt Around Nottingham with Hidden Gems (From £24.41)

- (0.02 mi) Lace Market Hotel

- (0.06 mi) Heritage Mews

- (0.09 mi) Lace Market Apartments

- (0.16 mi) Ibis Nottingham Centre

- (0.20 mi) Mercure Nottingham City Centre George Hotel

- (0.00 mi) Pitcher & Piano Nottingham

- (0.01 mi) Robe Room

- (0.01 mi) Iberico World Tapas

- (0.01 mi) Cock & Hoop

- (0.03 mi) Lace Market Hotel

Inspiring tales of justice

Hear true stories brought to extraordinary life.

Meet amazing, costumed characters from Nottingham's history in our Grade II* listed Shire Hall. Explore the Victorian Courtroom, Georgian gaol, and ancient cells - all spread over five fascinating floors. Be inspired by exhibitions on themes of social justice, and discover our captivating collection. Experience justice and the law like never before.

Adventures in history

Our thriving events programme explores the museum’s rich history and its unique collections in entertaining, intriguing and thought-provoking ways.

Saturday 1 June, 10:30am-12:30pm

Green Hustle - One Step at a Time

Saturday 1 June, 10am-4pm

Green Hustle - Messages of Hope

Friday 21 June, 2:30pm-4:30pm

Nottingham Refugee Week 2024

Saturday 15 June, 11am-3pm

Nottingham Refugee Week Launch 2024 - Words of Welcome

Friday 7 June, 1pm-3pm

Nottingham Poetry Festival - Roving Poet

Until Sunday 21 July 2024

Project Lab - Re-Present

Thursday 28 November - Saturday 21 December 2024, 6.30pm

The Spirit of Solstice: A Festive Murder Mystery

Thursday 30 May, 6pm - 8pm

Crime Club: The Reprieved

Thursday 25 July, 6pm - 8pm

Crime Club: A Day In Court

Select dates April - September 2024

Guilty?! - A National Justice Museum Escape Room

Saturday 10 February - Sunday 3 November 2024

Juvenile In Justice

Friday 24 May, 10am-12pm

How we tell our stories.

Friday 7 June, 10am-12pm

Body and Space Drawing Workshop

Friday 14 June, 10am-12pm

Found Poetry - Special Nottingham Poetry Festival Workshop

Friday 21 June, 10am-12pm

Our Home - Special Refugee Week Workshop

Friday 28 June, 10am-12pm

Rethinking Rehabilitation and Justice for All

Saturday 24 August 2024, 7pm

Dead to Writes - Cocktails & Crime

Excellent place so much to see, read and hear and fantastic actors staying true to their characters. we thoroughly enjoyed our visit, a fascinating day out and well worth the admission fee well done, good value for money, are you ready to join us.

Experience the harsh realities of life on the wrong side of the law. At the National Justice Museum we’re ready to share an adventure you’ll never forget. The question is, are you ready to join us?

Inspiring minds

Share a unique learning experience.

Sparking imaginations and inspiring minds, our unique curriculum-linked learning programmes for children and young people offer true-to-life workshops in real courtroom settings. Through immersive and engaging digital sessions, we illuminate justice, the law and its practise in a way learners will never forget. Plan a visit today.

Inspiring thinking

Read about our latest exhibitions, activities and initiatives about justice and the law.

National Justice Museum celebrates the life of its patron Lord Judge

National Justice Museum celebrates the life of its patron Lord Judge. Lord Judge was the former Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales and patron of our organisation.

National Justice Museum and City of Caves Recognized as Tripadvisor® 2023 Travellers’ Choice® Award Winners

Two iconic Nottingham attractions, the National Justice Museum and the City of Caves, today announced they have each been recognized by Tripadvisor as a 2023 Travellers’ Choice award winner. The coveted award celebrates businesses that have consistently received great traveller reviews on Tripadvisor over the last 12 months, placing these winners among the 10% of all listings on Tripadvisor globally.

An iconic piece of LGBTQ+ history returns to public display at the National Justice Museum

Oscar Wilde’s cell door from Reading Gaol, where he was incarcerated for “gross indecency”, was previously loaned to Queer Britain in London

National Justice Museum is awarded a £249,996 grant by The National Lottery Heritage Fund

The funding will allow the iconic Nottingham venue to create new job roles, deliver more workshops across the country, and create a brand-new escape room attraction.

Immersive, site-specific performances come to the National Justice Museum for one day only

Four experimental performances will be scattered throughout the historic gaol for curious visitors to find

National Justice Museum's Open Court podcast back for a second season

Retired Judge and former Barrister John Burgess leads a series of interviews taking you behind the scenes of the Justice system

Family devastation brought closer to home in knife crime prevention workshops

The heart-breaking accounts of Nottinghamshire families who lost loved ones to knife crime will be added to an award-winning workshop.

National Justice Museum announce recipient of £1000 photography award

The National Justice Museum has announced the recipient of a £1000 prize as part of their Freedom photography exhibition. The award includes a creative residency at the National Justice Museum in 2023 with a £1,000 budget, decided by a panel of esteemed and expert photographers Brian Griffin, Amanda Sinclair, and Ofilaye.

National Justice Museum recognised as one of England’s outstanding cultural organisations through Arts Council England’s National Portfolio

The scheme highlights leading arts and heritage organisations in the country and comes with over £700,000 of investment for the Lace Market venue

National Justice Museum’s new open-call photography exhibition, Freedom, to open in November

The exhibition opens on Saturday 12 th November and will feature over 200 black and white images submitted by the public

The National Justice Museum explores untold stories of Black presence

Tours, events, and displays are planned throughout October in the culmination of months of research into Black presence at the historic site

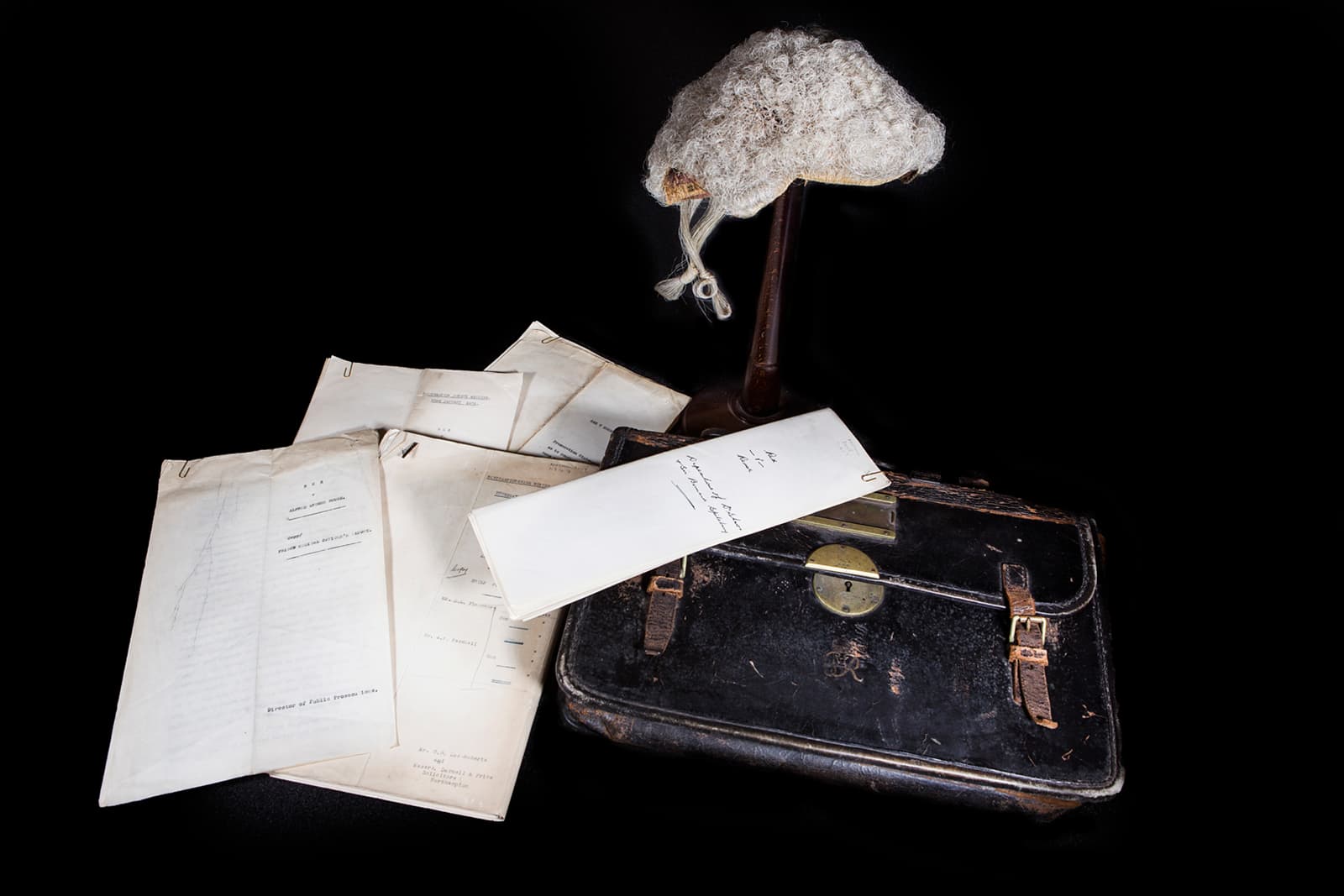

National Justice Museum opens call out for object donations from Black Legal Professionals

The National Justice Museum is looking to expand its collection to reflect the diversity within the legal profession, and to share the lived experiences and the contributions made by Black legal professionals.

National Justice Museum announces judges for Freedom photography competition

World world-renowned photographer, writer and director Brian Griffin leads a panel of judges for the National Justice Museum’s open call photography exhibition on the theme of Freedom. Griffin, along with fellow judges Amanda Sinclair and Ofilaye, will choose from hundreds of applicants to award a creative residency at the National Justice Museum in 2023 with £1,000 budget for the lucky winner.

National Justice Museum Wins 2022 Tripadvisor Travellers’ Choice Award

National Justice Museum today announced it has been recognised by Tripadvisor as a 2022 Travellers’ Choice award winner. The award celebrates businesses that have received great reviews from travellers around the globe on Tripadvisor over the last 12 months. As challenging as the past year was, National Justice Museum stood out by consistently delivering positive experiences to travellers.

Rolls Building Art and Education Trust & The Technology and Construction Court Art Competition

2023 is the 150th anniversary of The Technology and Construction Court (TCC), a major specialist Court that deals with disputes about building, engineering and all kinds of technology including software. The TCC is based in the Rolls Building, a spacious and modern courthouse in London's legal heartland.

As part of the anniversary celebrations, there will be a competition for young artists. Entries can be 2D artworks in any medium (except exclusively photography) and relate to the themes of Construction or Technology.

National Justice Museum opens submissions for photography exhibition with a £1,000 prize at stake

The call out is open to photographers from around the UK, from professionals to amateurs

National Justice Museum to receive £362,900 in fund which helps safeguard nation's cultural heritage

The National Justice Museum in Nottingham has been awarded a grant of £362,900 by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sports, delivered by Arts Council England.

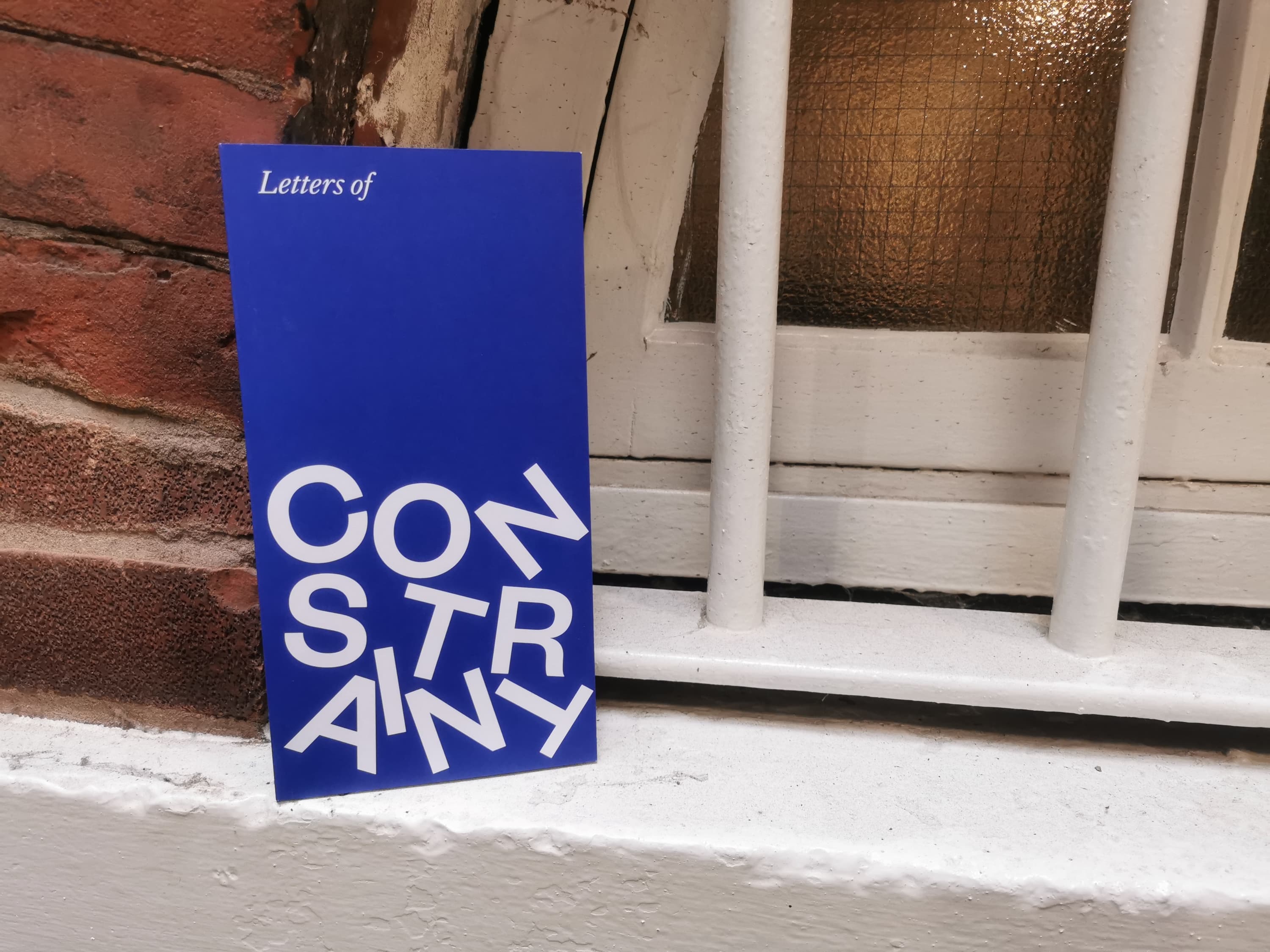

The National Justice Museum publishes Letters of Constraint

The newly released book is an intimate collection of letters and diary entries from lockdown

National Justice Museum wins Best Museums Change Lives Project at Museums Change Lives Awards 2021

The National Justice Museum has been awarded the Best Museums Change Lives Project at this year’s Museums Change Lives awards for our Make it Yours: Workshops in an Envelope project.

Welcome back S.H.E.D!

For two weeks in August 2021 summer, the National Justice Museum hosted a variety of exciting events, film screenings, talks and activities as part of S.H.E.D - the Social Higher Education Depot.

‘Freed Soul’ letters

For Women’s History Month 2021, we’re sharing a collection of Charlotte Bryant letters from our archives.

Justice week 2021

An interview with His Honour Judge John Burgess about the impact of COVID-19 on legal proceedings in Nottingham.

Ghost stories with Claire

We catch up with our former ghost tour extraordinaire Claire Finn to see whether she has any spooky stories to tell.

Autism and me

Michael, one of our educational facilitators at the National Justice Museum tells up about the positives of being Autistic.

Staying proud

With so many changes within legislation and human rights, the question has emerged in recent years; why is Pride still relevant?

Ultimate travel list

We’re delighted that the National Justice Museum has been chosen as one of the 500 top experiences and hidden gems in Great Britain.

The ‘Bloody Code’?

The Bloody Code imposed the death penalty for over 200 offences – many of which were surprisingly trivial.

Sandford award

Nottingham’s National Justice Museum has received a prestigious Sandford Award for Heritage Education.

National Justice Museum is an Educational Charity, registered number 1030554.

Check out our partner attraction venue:

What are you looking for?

Quick links.

- Book tickets

Blog Government Digital Service

https://gds.blog.gov.uk/2014/09/15/you-can-now-book-a-prison-visit-online/

You can now book a prison visit online

Booking a prison visit should be simple and straightforward. Until now that was far from the case. Booking a visit required both prisoner and visitor to jump through hoops: paper forms and drawn-out phone calls. And if the visit date turned out to be impossible, they had to start all over again.

Now you can book a visit online . It takes about 5 minutes. Before, picking an available date was pot luck. Now there's a date-picker that lets you select 3 possible slots instead of 1. It’s a straight-forward service with user-needs at its heart but, if you get stuck, you can call the prison's visits booking line and someone will help you with the booking.

Here's a very short film we've made about it:

By making it easier to book visits, prisoners will see more of their friends and family. Evidence suggests this will help their rehabilitation. Transformation isn't just about websites.

The service was built by the Ministry of Justice, with a combined team from the National Offender Management Service, HM Prison Service and MoJ Digital Services.

For more of the story behind this service, read Mike Bracken's account of his trip to HMP Rochester or check out the service’s transformation page .

Join the conversation on Twitter , and don't forget to sign up for email alerts .

You may also be interested in:

- Prison visit booking: using digital analytics to inform alpha development

- Making prison visits easier to book

- Meet the Transformation team

Sharing and comments

Share this page, 20 comments.

Comment by Pauline posted on 23 August 2015

How do you find out the prisoners number??? so you can go ahead with online booking of a visit?

Comment by Carrie Barclay posted on 24 August 2015

You can find a prisoner using this service: https://www.gov.uk/find-prisoner However it will be the prisoner's responsibility to get in touch with you to let you know their prison number etc.

Comment by linda posted on 15 August 2015

This service does not appear to work this is day 2 trying to use it

Comment by Olivia posted on 30 July 2015

Hi, If a visit is booked and someone cant make it, is it possible to change the name of one of the people to someone else?

Comment by Louise Duffy posted on 30 July 2015

It's best to contact the prison directly if this happens. You can find contact details here: http://www.justice.gov.uk/contacts/prison-finder

Thanks, Louise

Comment by Paige posted on 28 July 2015

Hi my partner was sent to nottingham today, I was on his previous list 4 months ago for a visit. Will that still be on the system all will it have to he put through again if so how long does it take to be approved for a visit? Thanks Paige.

Comment by Louise Duffy posted on 29 July 2015

You might want to get in touch with the prison first before booking a visit. You can find the contact details of the prison here: http://www.justice.gov.uk/contacts/prison-finder

Comment by Debs posted on 27 July 2015

Hello Is there a list of prisons where online booking can't be used?

Comment by Louise Duffy posted on 28 July 2015

According to the information on this page: https://www.gov.uk/prison-visits , you can arrange a visit to any prison in England and Wales through this service. If you're visiting someone in Northern Ireland or Scotland you'll need to contact the prison directly.

This link also lists the type of visits that are not covered by the online service: https://www.gov.uk/prison-visits so you need to get in touch with the prison directly.

Hope that's helpful.

Comment by c.steer posted on 26 July 2015

So how do I find the booking form to fill in I am new to computers

Comment by Louise Duffy posted on 27 July 2015

Here's the link to the booking form: https://www.gov.uk/prison-visits

You'll need this information to complete the form:

prisoner number prisoner’s date of birth dates of birth for all visitors coming with you make sure the person you’re visiting has added you to their visitor list

Hope that's useful.

Comment by Shawnaa posted on 09 May 2015

i have a visit booked which i did online but i do not have a visiting order woll the prison let me in?

Comment by Carrie Barclay posted on 11 May 2015

Your identity will be checked on arrival to make sure you’re on the visitor list.

Comment by jessicca posted on 27 January 2015

What happens after you book the visit and its confirmed by email do you need the visiting order ?

Comment by Carrie Barclay posted on 29 January 2015

The Visiting Order (VO) number is generated by the booking system, it is included in your confirmation email and you will need this to change or cancel a booking.

However, if you're visiting a prison the guidance is that you only need your ID, not the VO number. If when you visit the prison you are asked for the VO number you should report this via the Contact Us link on the Prison Visits Booking form.

I hope that helps.

Comment by Ilysa Mcnally posted on 18 November 2014

How late in advance can I book e.g. book a visit today (Tuesday) for the Sunday coming???

Comment by Carrie Barclay posted on 19 November 2014

Hi Ilysa. Thanks for your question. A visit needs to be booked 3 working days in advance. So in this case, the visit request would have to be no later than Tuesday to allow for a visit on Sunday.

Comment by carole posted on 23 October 2014

How far in advance can you book visits

Comment by Carrie Barclay posted on 23 October 2014

Hi Carole. You can book up to 28 days in advance. Thanks for your question.

Comment by kimberly posted on 16 August 2015

does anyone know how to cancel a visit online?

Related content and links

Government digital service.

GDS is here to make digital government simpler, clearer and faster for everyone. Good digital services are better for users, and cheaper for the taxpayer.

Find out more .

Sign up and manage updates

Be part of the transformation.

If you’re interested in joining us, check out all open opportunities on the GDS careers site.

- GDS Podcasts

Recent Posts

- How we’re using Webinars to demonstrate how quick and easy it is to use GOV.UK Forms 28 February 2024

- How we are improving GOV.UK Pay with user satisfaction feedback 29 January 2024

- How we migrated our PostgreSQL database with 11 seconds downtime 17 January 2024

Comments and moderation

Social media house rules.

Read our guidelines

HMP Nottingham, General Information

HMP Nottingham opened in 1890 as a city gaol but was reconstructed in 1912, and until 1997 served as a closed training establishment for adult males. In 1997, D wing and E wing were opened and the prison became a category B local establishment serving local courts in Nottingham and Derby. In 2005, F wing, G wing and the separation and reassessment unit were opened and B wing was decanted. All the original Victorian prison was demolished in 2008, with only part of the gatehouse and the wall remaining. Work to rebuild an expanded prison was completed in February 2010. The new prison has been in operation since 15 March 2010.

The prison is located close to the centre of Nottingham and accommodation is made up of seven main residential wings which hold up to 900 prisoners. The #1 governor is called Paul Yates , who has been in charge since February 2022, and the prison is part of the North Midlands area and run by HMPS.

Accommodation

- A wing – mainstream location

- B wing – mainstream location

- C wing – mainstream location

- D wing – mainstream location

- E wing – young adults

- F wing – first night centre and induction unit

- G wing – vulnerable prisoner unit

Return to Nottingham

Share this:

‘If you decide to cut staff, people die’: how Nottingham prison descended into chaos

As violence, drug use and suicide at HMP Nottingham reached shocking new levels, the prison became a symbol of a system crumbling into crisis

W hen Denise Ireson’s neighbour heard her son was going to prison, he issued a warning: just pray Ben isn’t sent to Nottingham. The neighbour’s relative worked in prisons, and he knew HMP Nottingham had a reputation for drugs, violence and suicide. This wasn’t exactly classified information. Since 2014, a series of alarming headlines had emerged. A prisoner bit off and, it’s believed, swallowed an officer’s right earlobe. An 80-year-old prisoner was throttled to death with a sheet while watching snooker in his cell. Another man was asphyxiated on his second day in the prison. His cellmate stabbed him with plastic cutlery, strangled him with a ligature made from shoelaces and put a plastic bag over his head. According to Steven Ramsell, a local criminal defence lawyer, conditions became so bad that some of his clients refused to board the bus that took them to the prison. “Nobody wanted to be in a prison,” Ramsell said. But more than anything, “nobody wanted to be in Nottingham prison”.

On 16 October 2018, Ben Ireson – a slender 31-year-old with a history of anxiety – arrived at Nottingham to await sentencing for a domestic violence charge. Allocated to the B wing, he called his mother six or seven times a day from the phone in his cell. On 22 October, Ben informed a staff member that he was under threat from other prisoners and that his cell had been robbed three times – teabags, biscuits and his crucifix were missing. That evening, he told his mother he’d attempted suicide and that he intended to try again. Denise yelled at him to hold out. At the time, she was caring for her grandson who had brain cancer. She spent the evenings alone in her flat worrying that Ben wouldn’t survive, either.

In the early hours of 13 December, an officer passed Ben’s cell and noticed that the observation hatch was covered with toilet roll. Peering through a crack, he saw Ben hanging from his wardrobe. The officer shouted to his colleague and called Code Blue on his radio, triggering the control room to call an ambulance. Staff cut Ben down and started CPR. Minutes later, when a nurse arrived, she advised them to stop: rigor mortis had already set in. Ben was pronounced dead at 6am. His was the 12th suicide at Nottingham in 18 months.

Just over a year later, an inquest revealed the catalogue of failings preceding Ben’s death. On arrival at the prison, Ben had told staff he had attempted suicide after a previous breakup. He should have been assessed by the mental health team within five days. When he was finally seen, a month later, it was by a trainee who hadn’t been given any information about him. When Ben complained that his belongings were being stolen, that he felt threatened and wanted to kill himself, he was placed on a suicide and self-harm prevention plan. Two days later, this monitoring stopped. Staff believed his condition had improved. At the inquest, Nottingham’s then governor, Phil Novis, described the state of the prison when he arrived in July 2018, five months before Ben’s death. “It was the worst prison I have ever been to. It was absolute chaos. There were no systems in place. There was just nothing. It was just … it was horrendous.”

At the start of 2018, Nottingham had become the first prison in Britain to be issued with an urgent notification , a new form of special measures reserved for the most dangerous institutions. “Inspection findings at HMP Nottingham tell a story of dramatic decline since 2010,” wrote Peter Clarke , then chief inspector of prisons. The report that accompanied the urgent notification – which followed poor inspection reports in 2015 and 2016 – described Nottingham as “a dangerous, disrespectful, drug-ridden jail” and raised a litany of concerns. Staff were being assaulted at twice the rate of their counterparts in other prisons. Prisoners were increasingly turning to self-harm. Eight men had taken their own lives since the last inspection.

How did Nottingham get so bad? Over the past year, I have interviewed more than 60 people – prisoners, prison staff, lawyers, academics, officials and families – to piece together how the prison unravelled. (The Ministry of Justice did not grant me permission to visit HMP Nottingham and rejected multiple requests to interview former governors and the prison chaplaincy team.) These interviews, alongside documents, inspection reports and inquest recordings, paint a vivid picture of Nottingham’s disintegration – at one inquest, an officer likened the prison to a war zone .

But the story of Nottingham is not one of individual crisis; it is a particularly shocking symbol of a nationwide crisis. Between 2009 and 2019, deaths in custody in English and Welsh prisons increased by 86%, while serious assaults on staff increased by 228%. “This decline was due to policy and political decisions, not suddenly a whole load of prison staff and prison governors deciding they were going to down tools and do a bad job,” Nick Hardwick, chief inspector of prisons from 2010 to 2016, told me. “It’s really important to understand that in prisons – as in other public services – this is a systemic issue.”

A s a category B local men’s prison, HMP Nottingham houses all sorts of prisoners: men waiting to be sentenced; men serving short sentences for minor crimes; men who have committed serious crimes who are waiting to be transferred to other prisons. A shoplifter might be held alongside a convicted murderer. According to the criminologist Philippa Tomczak, the constant turnover in local prisons feeds instability. One former Nottingham officer told me that local prison is the most dangerous place to work, because of the unknown. Drawn from an urban region with high levels of homelessness, drug use and organised crime, this revolving population is confined within around a dozen modern red-and-white blocks, the largest of which looks like a vast warehouse.

There were many reasons why things went so wrong at Nottingham, but staff and prisoners seem to agree on two major problems: first, there were too many prisoners, and second, there were not enough experienced officers. By January 2018, when Nottingham was issued its urgent notification, it had the capacity to house 718 men without being classed as overcrowded, but was holding almost 1,000. Across England and Wales, this kind of overcrowding was becoming the norm . (Scotland and Northern Ireland have devolved prison systems and so publish their own statistics.)

England and Wales not only locks up a greater percentage of its population than anywhere else in western Europe, but also locks them up for longer. There are more prisoners serving life sentences in England and Wales than in Italy, Germany, France, Belgium, Austria, the Netherlands, Sweden and Poland combined. England and Wales also impose harsh release conditions: when former prisoners break them, they return to custody. Roughly half of released prisoners are reconvicted within a year.

It wasn’t always this way. In the mid-90s, the prison population stood at roughly 40,000. But over the next few years, as Labour and the Conservatives competed to be seen as tough on crime, these numbers climbed steeply . Under New Labour, the prison population – which is disproportionately composed of men, minorities and people living with addiction and mental illness – reached 80,000 for the first time. In 2003, Martin Narey, director of the Prison Service, resigned in protest. “We could be turning people’s lives around,” he later said. “As long as numbers are continually rising, that’s not going to be possible.”

Rising numbers were, for a period, matched by rising investment. Between 2003 and 2008, prison expenditure in England and Wales increased by nearly 40% in real terms. “That investment reaped benefits,” says Andrea Albutt, head of the Prison Governors Association. “Prisons were performing as you would want prisons to perform. They were decent.” In 2008, an inspection report for Nottingham noted that while the prison was struggling with the growing number of prisoners, it was also “an effective local prison able to rise to many of the challenges it faced”.

Then the financial crisis struck, and the seeds of the present crisis were sown. In 2008, Jack Straw, the justice secretary, initiated a policy called benchmarking, which aimed to run prisons in the most cost-efficient way possible. The head of the Prison Service, Phil Wheatley, was asked to identify the best examples of cost-savings in individual prisons across the country, and then standardise these across every prison in England and Wales. If prisons tended to use five staff members to process 60 new prisoners, say, but Wheatley found a prison that did so with just three staff members, then he would investigate how they did it, and if it seemed effective and replicable, it would become the “benchmark” against which other prisons would be judged. Benchmarking enforced a kind of “levelling down” across prisons, making the bare minimum mandatory. Anything beyond this was considered to be wasteful, and was cut.

Identifying these benchmarks was a slow process, and in 2010, when the coalition government entered Downing Street and implemented austerity, it was still in its infancy. Rather than accelerating the policy, the new justice secretary Kenneth Clarke – who declared himself “amazed” that the prison population had doubled since he was home secretary in the early 90s – pledged to save money through privatisation and by reducing the number of prisoners. But in 2012, Clarke was replaced by Chris Grayling, who abandoned the pledge to reduce the prison population. Instead, he introduced the prison unit cost programme, an expansion of benchmarking. (This new policy initially garnered the support of the Prison Officers Association, the national union, because it replaced the planned privatisation.)

One of the things that makes prisons expensive to run is paying staff to run them. Grayling calculated that the quickest way to save a lot of money would be to employ fewer people and pay them less. To meet this goal, in 2013, the Ministry of Justice implemented a voluntary redundancy scheme. Thousands of long-serving officers on higher salaries left, saving money but leaving a void of experience in their wake. “You can’t get back experience,” said the former Nottingham officer.

Meanwhile, other cuts were starting to be felt. “We just couldn’t run prisons any more like we had done,” Andrea Albutt told me. By about 2013, she said that it had even become hard to procure socks and underwear for prisoners. As conditions deteriorated and staff found themselves stretched increasingly thin, a vicious cycle began where more and more officers signed off sick or resigned, meaning that some prisons were operating even below their benchmarked levels of staff.

During its time in office, the coalition government would cut prison budgets by 20% , and the number of prison staff would fall by almost 30%. “[Grayling] delivered on what David Cameron had asked him to do. But it’s at a considerable cost,” Wheatley told me. “Prisoners and staff are still paying.”

B y September 2013, Nottingham had lost 25% of its staff. Diane Ward was one of the officers who stayed. Ward – who has tawny hair, pale blue eyes and a robust commitment to straight-talking – had been in the Prison Service for three decades and was proud of her jailcraft. She knew that good officering requires a certain alchemy. Locks, bars, bolts, cameras and keys are crucial, but so are relationships. Because officers are outnumbered, they rely on the cooperation of those they lock up. This requires give and take. An officer is consistent and fair; they might turn a blind eye to certain transgressions. A prisoner shares snippets of information; they help keep order.

Ward joined Nottingham in 1997 and, until benchmarking started to affect the prison in 2013, she felt she could do her job properly. If she was working mornings, her alarm would ring, she’d fasten her hair, button her white shirt and lace up her Doc Marten boots. Passing through the prison’s gates, she would collect her keys. Then she’d head to the wing, unlocking and locking heavy metal gates along the way. Inside, it smelt faintly of bodies, an absence of fresh air, damp mops that hadn’t been wrung out properly.

Safe prisons run on routine. When the days were on track, Ward and her colleagues would unlock cells at 8am and prisoners would filter towards classes or work. (Working as painters and cleaners, serving meals and checking in new arrivals, prisoners can earn a weekly salary of about £12. They also earn revenue for the prison. If you’ve ever eaten airline food, your cutlery might have been packed by prisoners.) After work, during a leisure period known as “association”, prisoners could play pool, go to the gym, shower. Then they were locked in their cells until the morning. When this routine ran smoothly, the prison was quiet. Ward once worked a set of nights and the only alarm that rang was the fire alarm when she burned a slice of toast.

As staff numbers dwindled, these moments of calm disappeared. Formerly, officers were assigned to a wing for long stretches of time, so they could form relationships with prisoners, and pick up on when trouble was brewing. Now they became troubleshooters, deployed to multiple wings in a day. According to Albutt, governors were holding daily meetings to decide how to move staff around wings to plug gaps. “We used to call them swap shops,” she told me.

This constant churn didn’t just strain relations between staff and prisoners, it eroded solidarity among staff. Ward remembers a time when she found a prisoner who had a TV in his cell, which he wasn’t permitted. She ended up in a tug of war with him, yelling for help. Her colleagues on the landing didn’t appear. “I reported the two officers. Nothing happened,” Ward told me.

By 2014, staff shortages meant that prisoners’ activities were often cancelled. They could spend 21 hours a day in grim cells with graffitied walls and lidless toilets that were barely screened by stained, ragged curtains. Locked up for longer, prisoners became frustrated and more violent. It was around this time that Mark, a prison officer who had worked at Nottingham for more than a decade, started to feel unsafe. He recalled an incident in which a prisoner watered down a bowl of excrement until it formed a soup and then emptied it over a nurse’s head. Staff were being “potted” like this regularly, he said.

Mark was trained as a hostage negotiator, talking down men who barricaded themselves and other prisoners inside cells, showers and laundry rooms. These situations, he said, started to happen on a weekly basis. The prison regularly had to call on the support of a national riot squad, who are armed with shields and fireproof uniforms. The “nationals” were there so regularly, Mark said, that officers were on first-name terms with them. In 2010, the National Tactical Response group was called out to prisons across the country 118 times. During 2014, they were called 223 times . In April 2014, Steve Gillan, secretary general of the prison officers’ union, told the BBC that Nottingham was “a powder keg prison”.

As conditions deteriorated, Diane Ward began regularly filing security information reports (SIRs). She submitted roughly 100 between 2013 and 2015, lodging concerns about drugs and safety, as well as suspicions about potentially corrupt colleagues. Despite her persistence, the complaints seemed to disappear inside the prison intranet. Sometimes, when Ward was particularly irate, she would fire off emails to management:

“Please do something to support the good staff that are trying, but running out of the will to even bother.” “Dear Anyone who can tell me what we are doing.” “Is there really any point in submitting SIR’s!”

According to Albutt, similar scenes were playing out across the country. Austerity had not only reduced the number of officers, but administrative staff, too. Security reports would pile up, unread.

At the end of 2014, Ward booked a holiday to Australia. Before leaving, she sent emails to her manager outlining her concerns. “If the necessary changes aren’t made, I might just as well sit in my car, in the car park, for the good I do,” she wrote. “I have had enough of this awful place.”

The following year, Ward was accused of assaulting two prisoners. She admits to the first assault, saying that she pushed a man as she was trying to get him to go and have dinner. But she maintains that the second accusation was a stitch-up, planned between a prisoner and an officer. After being suspended for 143 days, Ward returned to work. She managed two shifts before being signed off for six months due to stress. She was later dismissed for being unable to do her job owing to ill health, so Ward took the prison to an employment tribunal. She claimed that the real reason for her dismissal were her criticisms of the way the prison was run. “I think they wanted to get rid of me to silence me,” she said in her witness statement.

Ward lost her case, but the judge upheld her concerns about safety in the prison. In the years that followed her suspension, the situation at Nottingham continued to decline at a terrifying rate.

I n 2015, a young man named Maurice McKenzie was recalled to Nottingham for breaking the conditions of his release. It had been three years since he was last inside, and he could see that the prison had changed. Prisoners were dominating the wings and officers didn’t seem to be able to stop them: “They lost control: fact,” he told me. There seemed to be more prisoners with severe mental illness. For two weeks, the man in the cell next door to him screamed throughout the night. “He don’t need prison. He can’t be locked up in a cell,” McKenzie told me.

Mental health is a grave problem in prisons across the country, but in Nottingham the problem may have been exacerbated by the fact that, at the time, patients from the nearby Rampton high-security psychiatric hospital were being automatically transferred to the prison if they had finished their treatment programmes but were deemed unfit for release into the community. Inspection reports in 2014 and 2015 flagged this as a major problem that the prison was not equipped to handle. (This policy of automatic transfer to Nottingham was subsequently amended.)

Around the time McKenzie returned to Nottingham, the justice select committee finished a year-long inquiry into the effects of “efficiency savings” in prisons, which made the link between funding cuts and a rise in prison deaths. In 2016, there were 119 suicides in English and Welsh prisons – twice as many as in 2012. The following year, self-harm incidents reached record numbers . That year, Frances Crook, then head of the Howard League for Prison Reform, gave evidence to parliament. “If you decide to cut staff, there are consequences; people die as a consequence,” she said. “Those are decisions that are made by politicians.”

In November 2016, in an effort to control the chaos its policies had unleashed, the government announced a recruitment drive to hire 2,500 officers. Having been stripped of experienced officers, prisons were now being filled with new recruits who were given as little as eight weeks training. (In Norway, officers are trained for two years .) At Nottingham, new officers were being sent into a particularly violent environment. A report published in February 2016 recorded 299 assaults on staff and prisoners in the previous six months, many of which involved weapons. One man who worked at Nottingham during this period recalled seeing a female member of staff being held down by her ponytail and kicked in the face. “If you have a jail that is at breaking point, don’t send inexperienced officers into that jail,” said former Nottingham prisoner Andrew Sedgwick.

There hasn’t been much research into the impacts of officering – prison officers sometimes refer to themselves as the forgotten service – but we do know that they suffer high levels of alcoholism, divorce and stress. Figures obtained by the BBC show that, in 2019, 1,000 prison officers in England and Wales were signed off due to stress. “My biggest regret in my life is going to work in the Prison Service,” says Mark, describing the toll taken by decades in the job. “It lives with you. I don’t know how many dead bodies I’ve seen in prison.”

Nottingham’s staff faced violence, but some abused their power. In April 2016, an officer assaulted a Black prisoner in his cell. In a WhatsApp group, the officer and two colleagues shared racist messages and agreed to lie to the prison investigation. One officer was later found guilty of common assault and all three were sentenced for misconduct in a public office. Eight months later, it emerged that another group of Nottingham staff had deliberately antagonised Black and Asian prisoners until they needed to be restrained, placed bets on who would win fights between officers and prisoners, and logged scores in a WhatsApp group.

These examples are extreme, but they reflect the evidence that those from ethnic minority backgrounds are both overrepresented in the criminal justice system, and have a worse time inside prison. It is unclear if any progress has been made since the 2017 Lammy Review into the justice system’s treatment of Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) individuals, which made 35 recommendations for reform. Earlier this year, in a new survey of BAME women prisoners, 40% of respondents had experienced discrimination, including racist abuse and prejudice from prison staff.

A s security was deteriorating, a new drug was tearing through British prisons. From around 2014, the synthetic cannabinoid spice, also known as mamba, was being smuggled in through visits, in the post, or with corrupt officers . In one case at Nottingham, the drug was sprayed on to a copy of Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, which was then torn up and sold for about £50 a strip.

Prisoners pay for drugs using bank transfers, known as “send outs”, or they pay in kind, using their canteen – a delivery of small items such as shampoo and deodorant that arrives on a Friday. Dealers provide the spice upfront and give the buyer a list of what they want; if they are not provided on time, the items on the list might be doubled. At Nottingham, a former officer told me, canteen day became known as “Black Eye Friday” because so many prisoners would get beaten up for failing to pay their debts.

Spice is popular in prisons because it’s hard to detect in drug testing. Its effects, though, are easy to spot. Sometimes, users slump into a state of oblivion, which helps melt away the hours in a cell. On other occasions, users start to behave violently or erratically. One prisoner, who served multiple sentences in Nottingham between 2010 and 2018, told me that he once saw a prisoner who was high on mamba trying to slice off his own penis. So many ambulances were called to the prison to treat drug-related episodes that they became known as Mambulances.

The combination of this rampant new drug and severe funding cuts could be lethal. At lunchtime on 27 September 2017, a Nottingham prisoner called Anthony Solomon rolled a spice cigarette from a page ripped out of the Bible. After smoking it, Solomon dropped to his knees and started vomiting and defecating. His cellmate rang the emergency cell bell.

Out on the wing, there was one officer for 220 men. New to the job, the officer was familiar with the effects of mamba, having previously been hospitalised after inhaling fumes while unlocking a cell. Alone on the lunch shift, the officer had to prioritise. He could begin the checks intended to prevent suicide and self-harm. Or he could start answering the cell bells, which prisoners rang constantly, often for minor reasons. He chose the former. About 40 minutes later, when another officer finally entered Solomon’s cell, he found him lying face-down in a pool of vomit. Shortly after, he was declared dead.

A mid this darkness, some prisoners still found light. One day, Ian McCluskey, a substance misuse recovery worker, was walking through the prison when he was intercepted by a prisoner called Garry Kinton, who asked for help getting sober.

When Kinton arrived at Nottingham in autumn 2017, around the time Solomon died, it was at least his 10th time in prison. He was 6ft 3in, skeletally thin and had yellow and black stumps for teeth. At night, he’d lie in his bunk – his angular spine jutting through the mattress, rubbing against the wooden slats – and think about his children, who had been put into care.

Kinton knew Nottingham’s reputation, and he was scared. In the four weeks after Solomon’s death, four prisoners had killed themselves. “I’d been in prison a lot of times. I hadn’t heard of that many deaths in such a short space of time,” Kinton told me. “It unnerved me.”

Kinton was on the “detox” wing, and drugs were everywhere. Prisoners queued to collect their subutex pills, a replacement for heroin, from the dispensary. They then often hid the pills under their tongues, sliced them into eight, and sold each slice for a tenner. Kinton hadn’t had a negative drugs test in 24 years, and assumed this would be his life. But then McCluskey agreed to help him.

McCluskey told me that he wanted to resist the apathy that naturally sets in after having seen so many prisoners try and fail to get sober. And so, even though Kinton wasn’t officially on his caseload, McCluskey decided to offer him emotional support and help secure him a spot in rehab for when he was released. A quarter of Nottingham’s prisoners are released without a fixed address, which is one of many overlapping factors that can lead to relapsing. “I am told, anecdotally, that if you have a drug problem then it takes about two hours for your drug dealer to get in touch with you,” says Graham Bowpitt, a professor in social policy at Nottingham Trent university.

With McCluskey’s support, Kinton queued for his last dose of methadone on 20 November 2017. He walked away from the dispensary and didn’t go back. “Encouragement is a massive thing,” Kinton told me. “A massive thing.” Just a few months earlier, he says he had no hope whatsoever. McCluskey helped change that. At the end of 2017, Kinton was released and stayed in the Carpenters Arms, a recovery centre that supports addicts. He is now a manager there, helping other people fight addiction.

P rison inspectors usually show up unannounced. But given that Nottingham’s previous two inspections had been so bad, the inspectorate gave advance warning that it would be arriving in January 2018. It made little difference. The subsequent report noted that just 12 of the 48 recommendations made in the last inspection had been fully implemented. Use of force had risen considerably, and 67% of surveyed prisoners said they felt unsafe. Although staff efforts were praised, inspectors noted that roughly half of staff based on the wings were in their first year of service, and many appeared passive and unconfident.

It was at this point that Nottingham was issued its urgent notification, and the prison’s failings became national news. Yet some argue that by focusing attention on individual failing prisons, urgent notifications can distract from just how widespread the rot has become. Nick Hardwick, the former prison inspector, told me that around 2013, the inspectorate had discussed whether they ought to actually lower standards because it was becoming impossible for prisons to meet them. They decided against this, because doing so would make it look as though everything was fine. “And it wasn’t.”

The systemic reasons for Nottingham’s decline are clear. But what role did the most senior individuals at the prison play in Nottingham’s continual decline? Mark, the former officer, certainly felt unsupported. “Senior management are like rocking horse droppings. You never see them,” he said. Phil Wheatley agrees that governors in prisons nationwide are more remote than they once were. But, he said, after benchmarking, “Governors were left with an impossible job and very often got blamed when it went wrong.” (Wheatley’s son, Tom Wheatley, was governor at Nottingham between 2016 and 2018 and is now governor of HMP Wakefield. The Ministry of Justice rejected my request to interview him.)

During its worst years, Nottingham’s governors didn’t remain in post for long. A 2016 inspection noted that the prison had had five governors in four years. Wheatley points out that this same problem was playing out in Westminster, too. In the past 10 years, there have been eight different secretaries of state for justice. Of course, Hardwick says, there were some examples of poor leadership at prisons like Nottingham. “But for the most part the buck had to stop at the door of the Ministry of Justice,” he told me.

When an urgent notification is issued, the Ministry of Justice is obliged to respond within 28 days, outlining an immediate action plan. As part of Nottingham’s short-term plan, pledges were made to remove young offenders from the prison and review use-of-force procedures. As part of a longer-term plan, then prisons minister Rory Stewart selected Nottingham to be part of a project that funnelled a total of £10m into 10 of the UK’s worst prisons, to fund new security measures, repairs and staff training. The resources were much needed. In September 2018, shortly after HMP Bedford became the fourth prison to be issued with an urgent notification, thousands of officers across the country staged a mass walkout . “We can’t just keep turning a blind eye to the broken limbs, the smashed eye sockets and broken jaws of our members,” Steve Gillan, general secretary of the prison officers’ union, told Sky News.

A year after Stewart’s project was launched, assaults had fallen in seven of the prisons. But at Nottingham they’d actually risen . In April 2019, a 23-year-old officer required 17 stitches after his throat was slit by a prison-issue razor. (According to Andrew Neilson, director of campaigns at the Howard League for Penal Reform, the rise in assaults at Nottingham might simply be due to an improvement in recording incidents, rather than an actual rise in violence.)

However, by the beginning of 2020, the situation at Nottingham looked slightly more hopeful. Although levels of self-harm and mental illness among prisoners remained high, there were also improvements. Drugs were being intercepted more often, prisoners could submit complaints via the electronic kiosks that had been installed on the landings, and the population had been reduced from a high of 1,074 to 798. Some new cultural projects had been introduced. Benje Howard, known as Kingdom Rapper, was brought in to teach prisoners how to rap. More than 200 men crowded into the gym to see him perform. “The atmosphere when I walked in was so jovial and electric,” Howard recalled.

“There is still a huge amount to do, but it would be wrong not to recognise the impressive progress that has been made,” concluded a report conducted in early 2020, before the pandemic. “When a previously poorly performing prison improves, I have seen how it is possible for a new and optimistic culture, offering real care for prisoners and a better chance for them to rehabilitate, can take hold.”

T wo years on, prisoners in England and Wales are still living with some of the restrictions that were implemented at the beginning of the pandemic; restrictions that saw many prisoners across the country confined to their cells for more than 22 hours a day . Once prisoners were locked down, rates of violence dropped. Now some staff are pushing to maintain the restricted regime indefinitely. “We have learned from Covid that lockdown is not a bad thing. It has returned control to the prison staff,” Mark Fairhurst, the chair of the prison officers’ union told the Times in July 2020. “Believe it or not, prisoners are telling us they like this regime. It is stable, they are not getting bullied by other prisoners.” Of course, if this is true, it raises deeper questions about why prisoners feel safer being locked inside their cells than engaging in some of the limited freedoms – education, work, exercise, visits – that should support their mental health and rehabilitation.

What is the situation like today at Nottingham? In a statement for this article, a Prison Service spokesperson said: “We have worked hard to improve HMP Nottingham by boosting staffing levels and installing a new X-ray body scanner to bolster security. Recent inspections show this is working, with a rapid fall in the amount of drugs entering the establishment and a reduction in violence.” The spokesperson also said that Nottingham has increased the number of specialist healthcare staff to support prisoners with mental health needs.

Yet worrying reports of violence and dire conditions continue to emerge from the prison. In July 2021, after an officer broke a prisoner’s arm in three places, the prisoner’s family held a protest outside the prison. (A Prison Service spokesperson said that an investigation into the use of force against the prisoner, Kyrone Moore, found it was proportionate.) A few months later, Stephanie Fogo, the mother of a prisoner named Richard Burnett, learned that his elbow had been broken, allegedly by an officer. (The prison is currently investigating the claims concerning Richard Burnett. In a statement responding to these allegations, a spokesperson told me: “Our highly trained officers use force as a last resort and in the overwhelming majority of cases it is unfortunately necessary to protect themselves or others from harm. All incidents involving use of force are investigated and anyone using disproportionate force can face dismissal and police investigation.”)

Since the alleged assault on her son, Fogo has received letters from prisoners detailing their treatment inside. “I didn’t know all these things were happening until it happened to my son,” Fogo told me. “No one, not one bloody person is doing anything about it.” The letters, which Fogo shared with me, raise a consistent set of concerns: poor food, prisoners going hungry, poor mental health support, and above all, abusive officers. (Though many of these same letters acknowledge that there are decent officers, too.)

“Constantly hungry and scared to even complain against the system + management in here, in case we get stitched up or staff turn against us, and it shouldn’t be like that.” “There’s a hell of a lot of inmates in here with mental health issues and it seems like staff don’t care!! […] Whats happened to the help we’re meant to get?” “I’ve been coming to this prison since 1999, in and out all the time, and my experience of doing time here has gone from bad to decent to OK to bad then to drasticly BAD with Capital letters!!! … By now, its nearly 2 years since Covid-19, and a structured plan should have been put in place by now? yet here we are, still being treated like cattle, with no light at the end of the tunnel.”

In October 2020, Peter Clarke wrote his final report as prisons inspector, warning that the challenges of recent years hadn’t disappeared. “When the immediate crisis is over, there will still be an urgent need to address the serious issues that adversely affect the safety and decency of our prisons.” Boris Johnson’s government, which campaigned on a traditional law and order ticket, have pushed for some innovation inside prisons; they’re encouraging companies to hire more ex-offenders and have advocated for internet installation inside cells. Day-to-day spending is back up significantly, largely due to more staffing. But the kind of reset Clarke recommended requires deeper consideration about what prisons actually are, and what we want them to be.

Late last year, the government published a white paper that outlined its plans. These included new facilities for prisoners dealing with drug and alcohol addiction and plans to help prisoners gain basic numeracy and literacy. If implemented, such measures may begin to address the crisis created by years of underfunding – not least chronic rates of reoffending. However, in his foreword, Dominic Raab began by trumpeting “the biggest prison building programme in more than 100 years,” and announced that the government “will provide 20,000 new prison places to protect the public through punishment and incapacitation of offenders”. The promise was to balance this punitive side of policy with targeted efforts at rehabilitating prisoners. But the latter is far more politically precarious. The slow, expensive, uncertain process of rehabilitating former prisoners is infinitely harder than building more prisons and locking more people up.

“They’re human beings,” says Denise Ireson, of the prisoners who have developed addictions, been assaulted, harmed themselves or taken their own lives. They’re somebody’s son, she says, somebody’s uncle, brother, grandson. “It’s us families that have lost our loved ones. We have to deal with this each and every day.”

Like all prisons, Nottingham gives the illusion of being severed from its city. But its connections run deep. The month Fogo found out her son had been beaten, Denise Ireson’s family gathered to mark the third anniversary of Ben’s death. As they had done for the last two years, they wrote notes to him on the side of helium balloons and released them into the sky. When the balloons floated away, Denise was left alone with her grief.

To cope, she lights candles in the memorial to Ben she has built in the corner of her flat. Three times a week, she visits Ben’s grave. When she dies, she will be buried next to him, with her epitaph etched on to the other side of the black marble headstone. Sometimes, Denise tends the grass, plucking weeds from the display she has created from artificial flowers and plastic meerkats, which Ben loved. Occasionally, she plugs in her headphones and, quietly, so she doesn’t disturb the other graves, she plays his favourite reggae song, Kingston Town. “The light seems to fade / But the moonlight lingers on / There are wonders for everyone / The stars shine so bright / But they’re fading after dawn.”

In the UK and Ireland, Samaritans can be contacted on 116 123 or email [email protected] or [email protected] . In the US, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is 1-800-273-8255 . In Australia, the crisis support service Lifeline is 13 11 14. Other international helplines can be found at www.befrienders.org

This article was amended on 22 June 2022. The National Tactical Response group was called out to prisons 118 times in 2010, not 18 times as stated in an earlier version.

- The long read

- Prisons and probation

Most viewed

- How we are run

- Our strategy

- Our statements

- Our funders

- Annual Reports

- Our committees

- Our policies

- Code of Ethics

- Anti-racism

- Collections

- Decolonising museums

- Learning and engagement

- Museums Change Lives

- Museums for Climate Justice

- Associateship (AMA)

- Museum Essentials

- Fellowship (FMA)

- Competency Framework

- Redundancy Hub

- Wellbeing Hub

- Career Conversations

- Entering the sector

- Conference 2024

- Forthcoming events

- Watch our webinars

- Conference 2023 content

- Esmée Fairbairn Collections Fund

- Benevolent Fund

- Beecroft Bequest

- Mindsets + Missions

- In practice

- Watch and listen

- Museums Journal

Behind bars | Juvenile In Justice, National Justice Museum, Nottingham

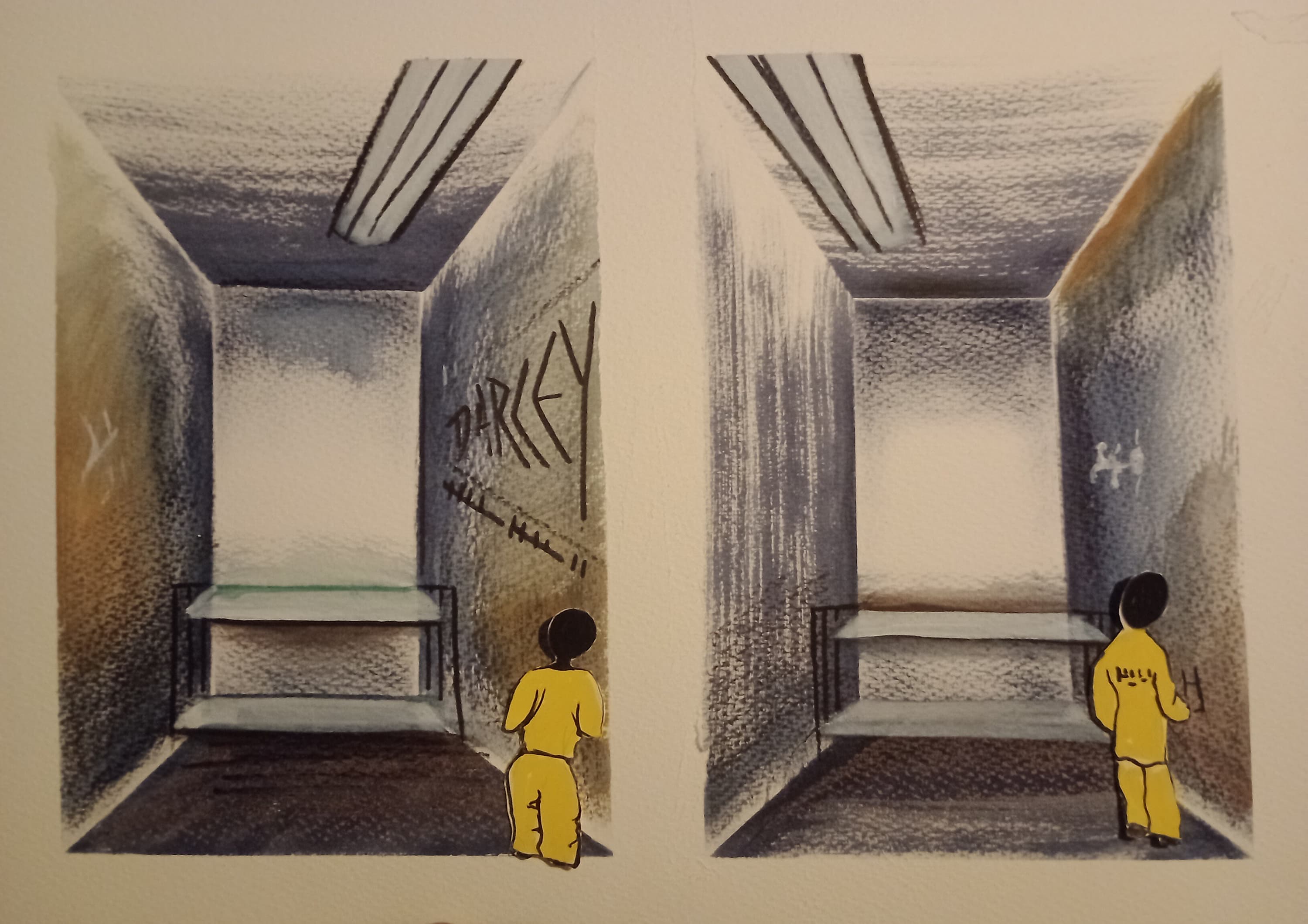

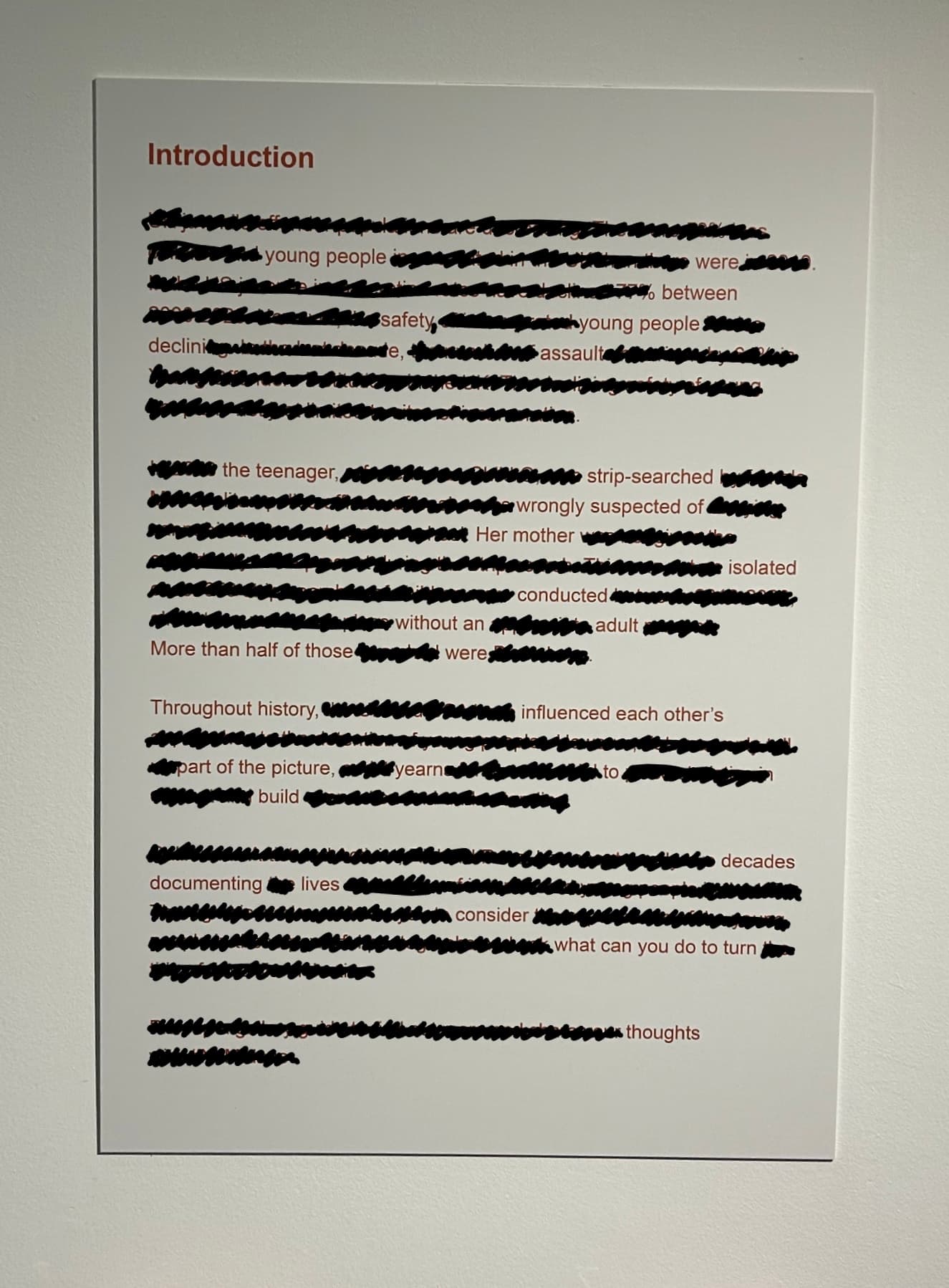

Juvenile In Justice, the new photography exhibition at Nottingham’s National Justice Museum, aims to offer a comparison between the justice systems of the US and the UK, inviting visitors to reflect on the lives of young people in prisons and detention centres.

The exhibition, which plays on the histories of justice in the two countries and the influence they have both had on each other, presents the work of California-based photographer Richard Ross alongside first-hand audio testimonials, a documentary and an engagement activity to prompt audiences to question what comes next, and how they can contribute to change.

Ross has spent the past 20 years visiting and documenting young people in prison across 35 US states and his photographs provide the foundation for the exhibition.