- location of the visitor¡¦s home ¡¦ how far they traveled to the site

- how many times they visited the site in the past year or season

- the length of the trip

- the amount of time spent at the site

- travel expenses

- the person¡¦s income or other information on the value of their time

- other socioeconomic characteristics of the visitor

- other locations visited during the same trip, and amount of time spent at each

- other reasons for the trip (is the trip only to visit the site, or for several purposes)

- fishing success at the site (how many fish caught on each trip)

- perceptions of environmental quality or quality of fishing at the site

- substitute sites that the person might visit instead of this site

- The value of improvements in water quality was only shown to increase the value of current beach use. However, improved water quality can also be expected to increase overall beach use.

- Estimates ignore visitors from outside the Baltimore-Washington statistical metropolitan sampling area.

- The population and incomes in origin zones near the Chesapeake Bay beach areas are increasing, which is likely to increase visitor-days and thus total willingness to pay.

- changes in access costs for a recreational site

- elimination of an existing recreational site

- addition of a new recreational site

- changes in environmental quality at a recreational site

- number of visits from each origin zone (usually defined by zipcode)

- demographic information about people from each zone

- round-trip mileage from each zone

- travel costs per mile

- the value of time spent traveling, or the opportunity cost of travel time

- exact distance that each individual traveled to the site

- exact travel expenses

- substitute sites that the person might visit instead of this site, and the travel distance to each

- quality of the recreational experience at the site, and at other similar sites (e.g., fishing success)

- perceptions of environmental quality at the site

- characteristics of the site and other, substitute, sites

- The travel cost method closely mimics the more conventional empirical techniques used by economists to estimate economic values based on market prices.

- The method is based on actual behavior¡¦what people actually do¡¦rather than stated willingness to pay¡¦what people say they would do in a hypothetical situation.

- The method is relatively inexpensive to apply.

- On-site surveys provide opportunities for large sample sizes, as visitors tend to be interested in participating.

- The results are relatively easy to interpret and explain.

- The travel cost method assumes that people perceive and respond to changes in travel costs the same way that they would respond to changes in admission price.

- The most simple models assume that individuals take a trip for a single purpose ¡¦ to visit a specific recreational site. Thus, if a trip has more than one purpose, the value of the site may be overestimated. It can be difficult to apportion the travel costs among the various purposes.

- Defining and measuring the opportunity cost of time, or the value of time spent traveling, can be problematic. Because the time spent traveling could have been used in other ways, it has an "opportunity cost." This should be added to the travel cost, or the value of the site will be underestimated. However, there is no strong consensus on the appropriate measure¡¦the person¡¦s wage rate, or some fraction of the wage rate¡¦and the value chosen can have a large effect on benefit estimates. In addition, if people enjoy the travel itself, then travel time becomes a benefit, not a cost, and the value of the site will be overestimated.

- The availability of substitute sites will affect values. For example, if two people travel the same distance, they are assumed to have the same value. However, if one person has several substitutes available but travels to this site because it is preferred, this person¡¦s value is actually higher. Some of the more complicated models account for the availability of substitutes.

- Those who value certain sites may choose to live nearby. If this is the case, they will have low travel costs, but high values for the site that are not captured by the method.

- Interviewing visitors on site can introduce sampling biases to the analysis.

- Measuring recreational quality, and relating recreational quality to environmental quality can be difficult.

- Standard travel cost approaches provides information about current conditions, but not about gains or losses from anticipated changes in resource conditions.

- In order to estimate the demand function, there needs to be enough difference between distances traveled to affect travel costs and for differences in travel costs to affect the number of trips made. Thus, it is not well suited for sites near major population centers where many visitations may be from "origin zones" that are quite close to one another.

- The travel cost method is limited in its scope of application because it requires user participation. It cannot be used to assign values to on-site environmental features and functions that users of the site do not find valuable. It cannot be used to value off-site values supported by the site. Most importantly, it cannot be used to measure nonuse values. Thus, sites that have unique qualities that are valued by non-users will be undervalued.

- As in all statistical methods, certain statistical problems can affect the results. These include choice of the functional form used to estimate the demand curve, choice of the estimating method, and choice of variables included in the model.

- GolfSW.com - Golf Southwest tips and reviews.

- VivEcuador.com - Ecuador travel information.

- TheChicagoTraveler.com - Explore Chicago.

- FarmingtonValleyVisit.com - Discover Connecticut's Farmington Valley.

Environmental Justice Organisations, Liabilities and Trade

Mapping environmental justice.

- Nuclear Energy

- Oil and Gas and Climate Justice

- Biomass and Land Conflicts

- Mining and Ship Breaking

- Environmental Health and Risk Assessment

- Liabilities and Valuation

- Law and Institutions

- Consumption, Ecologically Unequal Exchange and Ecological Debt

Travel-cost method

The travel-cost method (TCM) is used for calculating economic values of environmental goods. Unlike the contingent valuation method, TCM can only estimate use value of an environmental good or service. It is mainly applied for determining economic values of sites that are used for recreation, such as national parks. For example, TCM can estimate part of economic benefits of coral reefs, beaches or wetlands stemming from their use for recreational activities (diving and snorkelling/swimming and sunbathing/bird watching). It can also serve for evaluating how an increased entrance fee a nature park would affect the number of visitors and total park revenues from the fee. However, it cannot estimate benefits of providing habitat for endemic species.

TCM is based on the assumption that travel costs represent the price of access to a recreational site. Peoples’ willingness to pay for visiting a site is thus estimated based on the number of trips that they make at different travel costs. This is called a revealed preference technique, because it ‘reveals’ willingness to pay based on consumption behaviour of visitors.

The information is collected by conducting a survey among the visitors of a site being valued. The survey should include questions on the number of visits made to the site over some period (usually during the last 12 months), distance travelled from visitor’s home to the site, mode of travel (car, plane, bus, train, etc.), time spent travelling to the site, respondents’ income, and other socio-economic characteristics (gender, age, degree of education, etc). The researcher uses the information on distance and mode of travel to calculate travel costs. Alternatively, visitors can be asked directly in a survey to state their travel costs, although this information tends to be somewhat less reliable. Time spent travelling is considered as part of the travel costs, because this time has an opportunity cost. It could have been used for doing other activities (e.g. working, spending time with friends or enjoying a hobby). The value of time is determined based on the income of each respondent. Time spent at the site is for the same reason also considered as part of travel costs. For example, if respondents visit three different sites in 10 days and spend only 1 day at the site being valued, then only fraction of their travel costs should be assigned to this site (e.g. 1/10). Depending on the fraction used, the final benefit estimates can differ considerably.

Two approaches of TCM are distinguished – individual and zonal. Individual TCM calculates travel costs separately for each individual and requires a more detailed survey of visitors. In zonal TCM, the area surrounding the site is divided into zones, which can be either concentric circles or administrative districts. In this case, the number of visits from each zone is counted. This information is sometimes available (e.g. from the site management), which makes data collection from the visitors simpler and less expensive.

The relationship between travel costs and number of trips (the higher the travel costs, the fewer trips visitors will take) shows us the demand function for the average visitor to the site, from which one can derive the average visitor’s willingness to pay. This average value is then multiplied by the total relevant population in order to estimate the total economic value of a recreational resource.

TCM is based on the behaviour of people who actually use an environmental good and therefore cannot measure non-use values. This method is thus inappropriate for sites with unique characteristics which have a large non-use economic value component (because many people would be willing to pay for its preservation just to know that it exists, although they do not plan to visit the site in the future).

The travel-cost method might also be combined with contingent valuation to estimate an economic value of a change (either enhancement or deterioration) in environmental quality of the NP by asking the same tourists how many trips they would make in the case of a certain quality change. This information could help in estimating the effects that a particular policy causing an environmental quality change would have on the number of visitors and on the economic use value of the NP.

For further reading:

Ward, F.A., Beal, D. (2000) Valuing nature with travel cost models. A manual. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

Ecosystem valuation [ www.ecosystemvaluation.org/travel_costs.htm ]

This glossary entry is based on a contribution by Ivana Logar

EJOLT glossary editors: Hali Healy, Sylvia Lorek and Beatriz Rodríguez-Labajos

One comment

I quite like reading a post that will make people think. Also, thanks for allowing me to comment!

Browse by Theme

Browse by type.

- Presentations

- Press Releases

- Scientific Papers

Online course

Online course on ecological economics: http://www.ejolt.org/2013/10/online-course-ecological-economics-and-activism/

Privacy Policy | Credits

- View source

- View history

- Community portal

- Recent changes

- Random page

- Featured content

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

- Browse properties

Travel cost method

This article deals with the Travel Cost Method, which is often used in evaluating the economic value of recreational sites. This is particularly important in the coastal zone because of the level of use and the potential values that can be attached to the natural coastal and marine environment.

The Travel Cost Method (TCM) is one of the most frequently used approaches to estimating the use values of recreational sites. The TCM was initially suggested by Hotelling [1] and subsequently developed by Clawson [2] in order to estimate the benefits from recreation at natural sites. The method is based on the premise that the recreational benefits at a specific site can be derived from the demand function that relates observed users’ behaviour (i.e., the number of trips to the site) to the cost of a visit. One of the most important issues in the TCM is the choice of the costs to be taken into account. The literature usually suggests considering direct variable costs and the opportunity cost of time spent travelling to and at the site. The classical model derived from the economic theory of consumer behaviour postulates that a consumer’s choice is based on all the sacrifices made to obtain the benefits generated by a good or service. If the price ( [math]p[/math] ) is the only sacrifice made by a consumer, the demand function for a good with no substitutes is [math]x=f(p)[/math] , given income and preferences. However, the consumer often incurs other costs ( [math]c[/math] ) in addition to the out-of-pocket price, such as travel expenses, and loss of time and stress from congestion. In this case, the demand function is expressed as [math]x = f(p, c)[/math] . In other words, the price is an imperfect measure of the full cost incurred by the purchaser. Under these conditions, the utility maximising consumer’s behaviour should be reformulated in order to take such costs into account. Given two goods or services [math]x_1, x_2[/math] , their prices [math]p_1, p_2[/math] , the access costs [math]c_1, c_2[/math] and income [math]R[/math] , the utility maximising choice of the consumer is:

[math]max \, U = u(x_1,x_2) \quad subject \, to \quad (p_1+c_1)x_1+(p_2+c_2)x_2=R . \qquad (1)[/math]

Now, let [math]x_1[/math] denote the aggregate of priced goods and services, [math]x_2[/math] the number of annual visits to a recreational site, and assume for the sake of simplicity that the cost of access to the market goods is negligible ( [math]c_1 \approx 0[/math] ) and that the recreational site is free ( [math]p_2=0[/math] ). Under these assumptions, equation (1) can be written as:

[math]max \, U = u(x_1,x_2) \quad subject \, to \quad p_1x_1+c_2x_2=R . \qquad (2)[/math]

Under these conditions, the utility maximising behaviour of the consumer depends on:

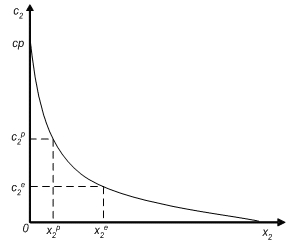

The TCM is based on the assumption that changes in the costs of access to the recreational site [math]c_2[/math] have the same effect as a change in price: the number of visits to a site decreases as the cost per visit increases. Under this assumption, the demand function for visits to the recreational site is [math]x_2=f(c_2)[/math] and can be estimated using the number of annual visits as long as it is possible to observe different costs per visit. The basic TCM model is completed by the weak complementarity assumption, which states that trips are a non-decreasing function of the quality of the site, and that the individual forgoes trips to the recreational site when the quality is the lowest possible [3] , [4] . There are two basic approaches to the TCM: the Zonal approach (ZTCM) and the Individual approach (ITCM). The two approaches share the same theoretical premises, but differ from the operational point of view. The original ZTCM takes into account the visitation rate of users coming from different zones with increasing travel costs. By contrast, ITCM, developed by Brown and Nawas [5] and Gum and Martin [6] , estimates the consumer surplus by analysing the individual visitors’ behaviour and the cost sustained for the recreational activity. These are used to estimate the relationship between the number of individual visits in a given time period, usually a year, the cost per visit and other relevant socio-economic variables. The ITCM approach can be considered a refinement or a generalisation of ZTCM [7] .

[math]x_2 = g(c_2) . \qquad (3)[/math]

The demand function can also be estimated for non-homogeneous sub-samples introducing among the independent variables income and socio-economic variables representing individual characteristics [8] . Therefore, if an individual incurs [math]c_2^e[/math] per visit, he chooses to do [math]x_2^e[/math] visits a year, while if the cost per visit increases to [math]c_2^p[/math] the number of visits will decrease to [math]x_2^p[/math] . The cost [math]cp[/math] is the choke price, that is the cost per visit that results in zero visits. The annual user surplus (the use value of the recreational site) is easily obtained by integrating the demand function from zero to the current number of annual visits, and subtracting the total expenditures on visits.

Related articles

- ↑ Hotelling, H. (1949), Letter, In: An Economic Study of the Monetary Evaluation of Recreation in the National Parks , Washington, DC: National Park Service.

- ↑ Clawson, M. (1959), Method for Measuring the Demand for, and Value of, Outdoor Recreation . Resources for the Future, 10, Washington, DC.

- ↑ Freeman, A.M. III. (1993). The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values: Theory and Method , Washington, DC: Resources for the Future.

- ↑ Herriges, J.A., C. Kling and D.J. Phaneuf (2004), 'What’s the Use? Welfare Estimates from Revealed Preference Models when Weak Complementarity Does Not Hold', Journal of Environmental Economics and Management , 47 (1), pp. 53-68.

- ↑ Brown, W.G. and F. Nawas (1973), 'Impact of Aggregation on the Estimation of Outdoor Recreation Demand Functions', American Journal of Agricultural Economics , 55, 246-249.

- ↑ Gum, R.L. and W.E.Martin (1974), 'Problems and Solutions in Estimating the Demand for and Value of Rural Outdoor Recreation', American Journal of Agricultural Economics , 56, 558-566.

- ↑ Ward, F.A. and D. Beal (2000), Valuing Nature with Travel Cost Method: A Manual , Northampton: Edward Elgar.

- ↑ Hanley, N. and C.L. Spash (1993), Cost Benefit Analysis and the Environment , Aldershot, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Definitions

- Articles by Paolo Rosato

- Integrated coastal zone management

- Evaluation and assessment in coastal management

- This page was last edited on 3 March 2022, at 21:18.

- Privacy policy

- About Coastal Wiki

- Disclaimers

Your Article Library

Methods used for the environmental valuation (with diagram).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

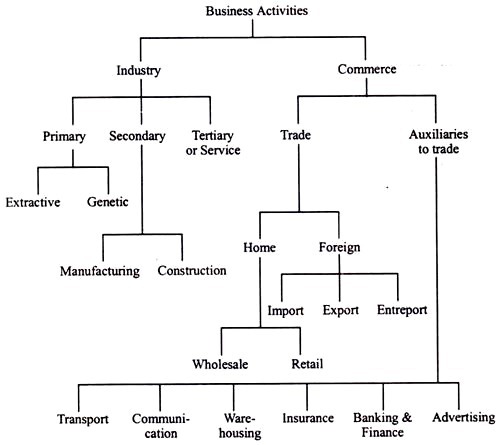

The following methods are used for environmental valuation:

(A) Expressed Preference Methods:

The demand for environmental goods can be measured by examining individuals’ expressed preference for these goods relative to their demand for other goods and services. These techniques avoid the need to find a complementary good (travel or house), or a substitute good (compensating wage rate), to derive a demand curve and hence estimate how much an individual implicitly values an environmental good. Moreover, expressed preference techniques ask individuals explicitly how much they value an environmental good.

Contingent Valuation Method (CVM):

Analytic survey techniques rely on hypothetical situations to place a monetary value on goods or services. Most survey-based techniques are examples of contingent valuation method. Contingent valuation frequently elicits information on willingness to pay or willingness to accept compensation for an increase or decrease in some usually non-marketed goods or services.

This method puts direct questions to individuals to determine how much they might be willing to pay for environmental resources or how much compensation they would be willing to accept if they were deprived of the same resources. This method is more effective when the respondents are familiar with the environmental good or service and have adequate information on which to base their preferences. We will discuss trade-off game method, costless-choice method, and Delphi method as part of contingent valuation approach.

(1) Trade-Off Game Method:

This method relates to a set of contingent valuation techniques that rely on the creation of a hypothetical market for some good or service. In a single bid game the respondents are asked to give a single bid equal to their willingness to pay or willingness to accept compensation for the environmental good or service described. In an iterative (repeating) bid game the respondents are given a variety of bids to determine at what price they are indifferent between receiving (or paying) the bid or receiving (or losing) the environmental good at issue.

The trade-off game method is a variant of the bidding game wherein respondents are asked to choose between two different bundles of goods. Each bundle might, for example, include a different sum of money plus varying levels of an environmental resource. The choice indicates a person’s willingness to trade money for an increased level of an environmental good. When no money is involved, the approach becomes similar to the costless-choice method.

(2) Costless-Choice Method:

The costless-choice method is a contingent valuation technique whereby people are asked to choose between several hypothetical bundles of goods to determine their implicit valuation of an environmental good or service. Since no monetary figures are involved, this approach may be more useful in settings where barter and subsistence production are common.

(3) Delphi Method:

The Delphi method is a variant of the survey-based techniques wherein experts, rather than consumers, are interviewed. These experts place values on a good or service through an iterative process with feedback among the group between each iteration. This expert-base approach may be useful when valuing very esoteric resources.

This is really a specialized survey technique designed to overcome the speculative and isolated nature of expert opinions. A sufficiently large sample of experts is presented individually with a list of events on which to attach probabilities and to which other events, with probabilities may be added. Some recent Delphi exercises have been recreation-specific. But testing the accuracy of their forecasts is not yet possible, especially since the predictions are only meant to be general perspectives.

(B) The Revealed Preference Methods:

The demand for environmental goods can be revealed by examining the purchases of related goods in the private market place. There may be complementary goods or other factor inputs in the household’s production function. There are a number of revealed preference methods such as travel- cost method, hedonic price method and property value method.

(2) The Hedonic Price Method:

The underlying assumption of the hedonic price method is that the price of a property is related to the stream of benefits to be derived from it. The method relies on the hypothesis that the prices which individuals pay for commodities reflect both environmental and non-environmental characteristics. The implicit prices are sometimes referred to as hedonic prices, which relate the environmental attributes of the property.

Therefore, the hedonic price approach attempts to identify how much of a property differential is due to a particular environmental difference between properties, and how much people are willing to pay for an improvement in the environmental quality that they face and what the social value of improvement is.

The hedonic price method is based on consumers which postulates that every good provides a bundle of characteristics or attributes. Again, market goods can be regarded as intermediate inputs into the production of the more basic attributes that individuals really demand.

The demand for goods, say housing can, therefore, be considered as a derived demand. For example, a house yields shelter, but through its location it also yields access to different quantities and qualities of public services, such as schools, centres of employment and cultural activities etc. Further it accesses different quantities and qualities of environmental goods, such as open space parks, lakes etc.

The price of a house is determined by a number of factors like structural characteristics, e.g. number of rooms, garages, plot sizes etc. and the environmental characteristics of the area. Controlling the non-governmental characteristics which affect the demand for housing, permits the implicit price that individuals are willing to pay to consume the environmental characteristics associated with the house to be estimated.

The hedonic price function describing the house price Pi of any housing unit is given below:

Pi = f [S 1i …………S ki , N 1i ,…………….N mi , Z 1i ………….Z ni ]

Where, S represents structural characteristics of the house i i.e. type of construction, house size and number of rooms; N represents neighbourhood characteristics of house i, that is accessibility to work, crime rate, quality of schools etc. It is assumed that only one environment variable affects the property value i.e. air quality (Z).

For example, if the linear relation exists, then the equation becomes

P i = [α 0 + α 1 S 1i + ….. + α K S Ki + β 1 N 1i + ……. + β m N mi + γ a Z a ]

and y a > 0.

There is a positive relation between air quality and property price as shown in Figure 50.2. The figure indicates that house price increases with air quality improvement.

Figure 50.3. indicates that the implicit marginal purchase price of Z a (air quality) varies according to the ambient level (Z a ) prior to the marginal change.

The hedonic price method has become a well-established technique for estimating the disaggregated benefits of various goods attributes. In the case of housing, these attributes include not only basic structural and amenity characteristics but also environmental characteristics such as clean air, landscape and local ecological diversity. Thus, when a particular policy is implemented which will have a very great effect on the local environment, the hedonic method offers a useful way of estimating the change in amenity benefits.

1. This method is of no relevance when dealing with many types of public goods i.e. defence, nation-wise air pollution and endangered species, etc., as it prices are available for them.

2. The hedonic price method may be used to estimate the environmental benefits provided to local residents by an area as it exists today. But in fact, it cannot reliably predict the benefits which will be generated by future improvements because those improvements will have the effect of shifting the existing function.

3. Another problem is whether an individual’s perceptions and consequent property purchase decisions are based upon actual or historic levels of pollution and environmental quality. If expectations are not the same as measured by present pollution estimate, then there are clearly problems relating to values derived from purchases.

4. Moreover, expectations regarding future environmental quality may bias present purchases away from that level dictated by present characteristic levels.

5. This method has been criticised for making the implicit assumption that households continually re-evaluate their choice of location.

6. Further, there is considerable doubt that such an assumption can hold in the context of spatially large study areas. If people cluster for social or transportation reasons, the results of this method will be biased.

(3) Preventive Expenditure Method:

The preventive expenditure method is a cost based valuation method that uses data on actual expenditures made to alleviate all environmental problems. Often, costs may be incurred to mitigate the damage caused by an adverse environmental impact. For example, if drinking water is polluted, extra purification may be needed. Then, such additional defensive or preventive expenditure could be taken as a minimum estimate of the mitigation of benefits beforehand.

In the preventive expenditure method, the value of the environment is inferred from what people are prepared to spend to prevent its degradation. The averting or mitigating behaviour method infers a monetary value for an environmental externality by observing the costs people are prepared to incur in order to avoid any negative effects.

For example, by moving to an area with less air pollution at a greater distance from their place of work thus incurring additional transportation costs in terms of time and money. Both of these methods are again, conceptually closely linked.

These methods assess the value of non-marketed commodities such as cleaner air and water, through the amount individuals are willing to pay for market goods and services to mitigate an environmental externality, or to prevent a utility loss from environmental degradation, or to change their behaviour to acquire greater environmental quality.

(4) Surrogate Markets:

When no market exists for a good or service and therefore, no market price is observed, then surrogate (or substitute) markets can be used to derive information on values. For example, travel-cost information can be used to estimate value for visits to a recreational area; property value data are used to estimate values for non-marketed environmental attributes such as view, location or noise levels.

The effects of environmental damages on other markets like property values and wages of workers are also evaluated. Valuation in the case of property is based on risks involved in evaluating the value of property due to environmental damage. Similarly, jobs with high environmental risks will have high wages which will include large risk premiums.

(5) Property-value Method:

In the property-value method, a surrogate market approach is used to place monetary values on different levels of environmental quality. The approach uses data on market prices for homes and other real estates to estimate consumers’ willingness to pay for improved levels of environmental quality, air, noise etc.

In areas where relatively competitive markets exist for land, it is possible to decompose real estate prices into components attributable to different characteristics like house, lot size and water quality. The marginal willingness to pay for improved local environmental quality is reflected in the increased price of housing in cleaner neighborhoods.

(C) Cost-Based Methods:

Cost-based methods are discussed below:

(1) Opportunity Cost Method:

This method values the benefits of environmental protection in terms of what is being foregone to achieve it. This forms the basis of compensation payments for the compulsory purchase by the government of land and property under eminent domain laws. Further, it assumes that the land owner or user has property rights over the use of the land or the natural resource, and that to restrict these rights the government, on behalf of the society, must compensate the owner.

The opportunity cost method is useful in cases where it is difficult to enumerate the benefits of an environmental change. For example, rather than comparing the benefits of various alternative conservation schemes in order to choose between them, the method can be used to enumerate the opportunity costs of foregone development associated with each scheme with the preferred option, being the one with the lowest opportunity cost.

The opportunity cost method does not include non-marketed public good values of land. The fact that land and its attributes produce externalities is explicitly recognised in regulatory land-use planning controls, which seek to minimize external bads through development control and land-use class orders, by separating externality producing land uses spatially.

Thus planning controls seek to preserve amenity benefits by restricting the development of land. However, by imposing such restrictions, the price of land, such as green belt land, has a lower financial value than its opportunity cost value.

(2) Relocation Cost Method:

This is a cost-based technique used to estimate the monetary value of environmental damages based on the potential costs of relocating a physical facility that would be damaged by a change in environmental quality. This method relies on data on potential expenditures.

(D) Other Methods:

There are some other methods of valuing the environment.

(1) Dose-Response Method:

This method requires information on the effect that a change in a particular chemical or pollutant has on the level of an economic activity or a consumer’s utility. For example, ground levels of air pollution, such as ozone, affect the growth of various plant species differentially. Where this results in a change in the output of a crop, the loss of output can be valued at market or shadow (adjusted or proxy) market prices.

Dose-response relationships or production function approaches, are perhaps the most familiar valuation techniques. Essentially, a link is established between say, a pollution level and a physical response, for example, the rate at which the surface of a material decays. The decay is valued by applying the market price (costs of repair) or by borrowing a unit valuation from non-market studies.

Notable examples include the valuation of health damage. Once air pollution is linked to morbidity and morbidity is linked to days lost from work, the days lost can be valued, perhaps using a market wage rate. The main effort of the analysis is devoted to identifying the link between dose and the response.

(2) Human Capital or Foregone Earning Approach:

The human capital approach values environmental attributes through their effects on the quantity and quality of labour. The loss earnings approach focuses on the impact which adverse environmental conditions have on human health and the resultant costs to society in terms of income lost through illness, accidents and spending on medical treatments.

The principle involved in this approach is that of valuing life in terms of the value of labour. Given adequate data regarding lifetime earnings, participation rates in the labour force mortality rates, etc., it is possible to estimate the value of the expected future earnings of individuals in any age- group.

On the assumption that wage rates are a precise indicator of productivity, the same measure with some adjustment to allow for social preferences being different from private preferences can be used as a measure of the value of the future output of the individual to society.

The social values emerging are usually referred to as the economic value of life. The other being non-economic or intangible aspects which are additional to that part of life which the method has been able to measure. This type of valuation system is the one most commonly found in practice.

The adjusted stream of life-time earnings has to be discounted to convert it to present value terms. This present value stream of future earnings with these various adjustments made, represents the human capital value of life span. In some cases, the measurement of lost output is taken net of consumption and in others a gross figure is used.

The reasoning behind the adoption of a net of consumption estimate is that when a worker dies due to an accident that occurs in a factory, the earnings of the workers will be stopped. The society loses the difference between what he would have produced and what he would have consumed.

Related Articles:

- Difficulties Faced During the Measurement of Environmental Values

- Valuing the Environment: Meaning and Need for Environment Valuation

Environment

No comments yet.

Leave a reply click here to cancel reply..

You must be logged in to post a comment.

The Travel Cost Approach to Recreation Demand Modeling: An Introduction

Cite this chapter.

- V. Kerry Smith 4 &

- William H. Desvousges 5

Part of the book series: International Series in Economic Modeling ((INSEM,volume 3))

61 Accesses

The travel cost approach offers some of the most widely used demand models for valuing recreation sites. Originally suggested in a letter from Harold Hotelling to the director of the National Park Service, the approach’s basic idea—i.e., that the distances recreationists travel to the sites they visit indicate the implicit prices they are willing to pay for using these sites—has spawned an extensive literature.* Drawing on this literature, this chapter introduces and develops our indirect approach for measuring households’ valuation of water quality changes. In particular, we generalize the travel cost model to reflect the role of recreation sites’ characteristics on households’ demands for the services of these sites.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Becker, Gary S., 1965, “A Theory of the Allocation of Time,” Economic Journal , Vol. 75, September 1965, pp. 493–517.

Article Google Scholar

Becker, Gary S., 1974, “A Theory of Social Interactions,” Journal of Political Economy , Vol. 82, 1974, pp. 1063–93.

Berndt, Ernst, R., 1983, “Quality Adjustment in Empirical Demand Analysis,” Working Paper 1397–83, Sloan Schools, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, January 1983.

Google Scholar

Bockstael, Nancy E., W. Michael Hanemann, and Catherine L. Kling, 1985, “Modeling Recreational Demand in a Multiple Site Framework,” paper presented at AERE Workshop on Recreational Demand Modelings, Boulder, Colorado, May 1985.

Bockstael, Nancy E., and Kenneth E. McConnell, 1981, “Theory and Estimation of the Household Production Function for Wildlife Recreation,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management , Vol. 8, No. 3, September 1981, pp. 199–214.

Bockstael, Nancy E., and Kenneth E. Monnell, 1983, “Welfare Measurement in the Household Production Framework,” American Economic Review , Vol. 73, No. 4, September 1983, pp. 806–14.

Bockstael, Nancy E., Ivar E. Strand. Jr. and W. Michael Hanemann, 1984, “Time and Income Constraints in Recreation Demand Analysis,” unpublished paper, Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland, March 1984.

Brown, Gardner. Jr. and Robert Mendelsohn, 1984, “The Hedonic Travel Cost Method,” Review of Economics and Statistics , Vol. 66, No. 3, August 1984, pp. 427–33.

Burt, O. R., and D. Brewer, 1971, “Estimation of Net Social Benefits from Outdoor Recreation,” Econometrica , Vol. 39, October 1971, pp. 813–27.

Cesario, Frank J., 1976, “Value of Time in Recreation Benefit Studies,” Land Economics , Vol. 52, No. 1, February 1976, pp. 32–41.

Cesario, Frank J., and Jack L. Knetsch, 1970, “Time Bias in Recreation Benefit Estimates,” Water Resources Research , Vol. 6, No. 3, June 1970, pp. 700–04.

Cesario, Frank J., and Jack L. Knetsch, 1976, “A Recreation Site Demand and Benefit Estimation Model,” Regional Studies , Vol. 10, pp. 97–104.

Cicchetti, Charles J., Anthony C. Fisher, and V. Kerry Smith, 1976, “An Econometric Evaluation of a Generalized Consumer Surplus Measure: The Mineral King Controversy,” Econometrica , Vol. 44, No. 6, November 1976, pp. 1259–76.

Clawson, M., 1959, “Methods of Measuring the Demand for and Value of Outdoor Recreation,” Reprint No. 10, Resources for the Future, Inc., Washington, D.C., 1959.

Clawson, M., and J. L. Knetsch, 1966, Economics of Outdoor Recreation , Washington, D.C.: Resources for the Future, Inc., 1966.

Desvousges, William H., V. Kerry Smith, and Matthew McGivney, 1983, A Comparison of Alternative Approaches for Estimating Recreation and Related Benefits of Water Quality Improvements , Environmental Benefits Analysis Series, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, March 1983.

Deyak, Timothy A., and V. Kerry Smith, 1978, “Congestion and Participation in Outdoor Recreation: A Household Production Approach,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management , Vol. 5, March 1978, pp. 63–80.

Dwyer, John F., John R. Kelly, and Michael D. Bowes, 1977, Improved Procedures for Valuation of the Contribution of Recreation to National Economic Development , Research Report No. 128, Water Resources Center, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1977.

Fisher, Franklin M., and Karl Shell, 1968, “Taste and Quality Changes in the Pure Theory of the True Cost-of-Living Index,” in J. N. Wolfe, ed., Value, Capital, and Growth: Papers in Honour of Sir John Hicks , Chicago: Aldine Publishing Co., 1968.

Freeman, A. Myrick III, 1979, The Benefits of Environmental Improvement: Theory and Practice , Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press for Resources for the Future, Inc., 1979.

Hausman, Jerry A., 1978, “Specification Error Tests in Econometrics,” Econometrica , Vol. 46, November 1978, pp. 1251–72.

Lau, Lawrence J., 1982, “A Note on the Fundamental Theorem of Exact Aggregation,” Economic Letters , Vol. 9, 1982, pp. 119–26.

McConnell, Kenneth E., and Ivar Strand, 1981, “Measuring the Cost of Time in Recreation Demand Analysis: An Application to Sport Fishing,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics , Vol. 63, No. 1, February 1981, pp. 153–56.

Mendelsohn, Robert, 1984, “An Application of the Hedonic Travel Cost Framework for Recreation Modeling to the Valuation of Deer" in V. Kerry Smith and Ann D. Witte, eds., Advances in Applied Micro-Economics , Greenwich: JAI Press, 1984.

Morey, Edward R., 1981, “The Demand for Site-Specific Recreational Activities: A Characteristics Approach,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management , Vol. 8, No. 4, December 1981, pp. 345–71.

Morey, Edward R., 1984, “Confuser Surplus,” American Economic Review , Vol. 74, No. 1, March 1984, pp. 163–73.

Morey, Edward R., 1985, “Characteristics, Consumer Surplus and New Activities: A Proposed Ski Area,” Journal of Public Economics , Vol. 26, March 1985, pp. 221–36.

Muellbauer, John, 1974, “Household Production Theory, Quality and the ’Hedonic Technique,” American Economic Review , Vol. 64, No. 6, December 1974, pp. 977–94.

Pollak, Robert A., and Michael L. Wachter, 1975, “The Relevance of the Household Production Function and Its Implications for the Allocation of Time,” Journal of Political Economy , Vol. 83, April 1975, pp. 255–77.

Ravenscraft, David J., and John F. Dwyer, 1978, “Reflecting Site Attractiveness in Travel Cost-Based Models for Recreation Benefit Estimation,” Forestry Research Report 78–6, Department of Forestry, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, Illinois, July 1978.

Shephard, Ronald W., 1953, Cost and Production Functions , Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953.

Smith, V. Kerry, 1975, “Travel Cost Demand Models for Wilderness Recreation: A Problem of Non-Nested Hypotheses,” Land Economics , Vol. 51, May 1975, pp. 103–11.

Smith, V. Kerry, William H. Desvousges, and Matthew P. Mivney, 1983a, “An Econometric Analysis of Water Quality Improvement Benefits,” Southern Economic Journal , Vol. 50, No. 2, October 1983, pp. 422–37.

Smith, V. Kerry, William H. Desvousges, and Matthew P. Mivney, 1983b, “The Opportunity Cost of Travel Time in Recreation Demand Models,” Land Economics , Vol. 59, No. 3, August 1983, pp. 259–78.

Smith, V. Kerry, and Yoshiaki Kaoru, 1985. "The Hedonic Travel Cost Model: A View from the Trenches,” unpublished paper, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, September 1985.

Talhelm, Daniel R., 1978, “A General Theory of Supply and Demand for Outdoor Recreation in Recreation Systems,” unpublished manuscript, Department of Agricultural Economics, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, July 1, 1978.

Vaughan, William J., Clifford S. Russell, and Jule A. Hewitt, 1984, “Measuring the Benefits of Recreation Related Resource Enhancement: A Caution,” unpublished working paper, Resources for the Future, April 1984.

Wilman, Elizabeth A., 1980, “The Value of Time in Recreation Benefit Studies,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management , Vol. 7, No. 3, September 1980, pp. 272–86.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA

V. Kerry Smith

Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA

William H. Desvousges

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 1986 Kluwer-Nijhoff Publishing, Boston

About this chapter

Smith, V.K., Desvousges, W.H. (1986). The Travel Cost Approach to Recreation Demand Modeling: An Introduction. In: Measuring Water Quality Benefits. International Series in Economic Modeling, vol 3. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-4223-3_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-4223-3_7

Publisher Name : Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN : 978-94-010-8374-4

Online ISBN : 978-94-009-4223-3

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Environmental Valuation: The Travel Cost Method

Related Papers

isabel mendes

Working Papers

Journal of Leisure Research

John Loomis

Mahidi Hasan kawsar , Muha Abdullah Al Pavel , Md Abdullah Al Mamun

Estimation of recreational benefits is an important tool for both biodiversity conservation and ecotourism development in national parks and sanctuaries. The design of this work is to estimate the recreational value and to establish functional relationship between travel cost and visitation of Lawachara National Park (LNP) in Bangladesh. This study employed zonal approach of the travel cost method. The work is grounded on a sample of 422 visitors of the LNP. Results showed that the total value of environmental assets of the LNP is 55,694,173 Taka/Year. Moreover, our suggestion based on visitors' willingness to pay is that the park entrance fee of 25 Tk per person should be introduced that could generate revenue approximate 2.3 million Taka/ year, beneficial for the park management and conservation of biodiversity.

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences

Kamarul Ismail

Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics

Clement Tisdell

Discusses the implications of the economic valuation of natural resources used for tourism and relates this valuation to the concept of total economic valuation. It demonstrates how applications of the concept of total economic valuation can be supportive of the conservation of natural resources used for tourism. Techniques for valuing tourism’s natural resources are then outlined and critically evaluated. Consideration is given to travel cost methods, contingent valuation methods, and hedonic pricing approaches before concentrating on current developments of valuation techniques, such as choice modelling. The general limitations of existing methods are considered and it is argued that more attention should be given to developing guidelines that will identify ‘optimally imperfect methods’. An overall assessment concludes this article.

David Kenworthy

International Journal of Emerging Trends in Engineering Research

WARSE The World Academy of Research in Science and Engineering

The challenge of providing adequate lighting along highways, particularly at critical points such as sharp turns and speed breakers, poses significant safety concerns. Traditional energy sources often fail to meet the demands of continuous lighting, especially in remote areas. To tackle this challenge, we present an automatic lighting system aimed at selectively activating lights during nighttime while also reducing vehicle speed near or at danger zones. Entire system is designed as automatic, human involvement is not required; lights are controlled automatically by sensing the vehicles. Whenever the vehicle enters into the danger zone, lights will be energized and they remain in ON state until the vehicle leaves that area. The system will be activated automatically during dark. In this method precious energy acquired from the solar panel can be saved. During the day time the battery will be charged and this stored energy is utilized in the nights[10]. It is a novel approach to vehicle navigation and safety implementation, and also aimed at automatically sensing the areas/zones like Schools, Hospital Accident, etc and automatically reducing the speed of the vehicle for safety purposes.

RELATED PAPERS

Gabrielle Abreu

Zakaria Mohammed

Marxism & Sciences

Martin Küpper

Angela Simalcsik

Roussos Dimitrakopoulos

Enrique Cabanilla V. , Edison Molina V.

Ponto Urbe: revista do núcleo de antropologia urbana da usp

Sarah Hissa

Intervention Press; Kriza János Ethnographic Society

Mária Szikszai

Environment and Ecology Research

Angelo Mark P Walag

SENSORY ANALYSIS OF GLUTEN-FREE FOODS MADE WITH GREEN BANANA FLOUR

Nádia M A C H A D O Santana

Physical Review C

George Lolos

Revista Chilena de Terapia Ocupacional

Veronica Veliz

Uswatun Chasanah

Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR

shalini bahadur

Public Health Nutrition

Rimante Ronto

Alevilik-bektaşilik araştirmalari dergisi

Electronic Journal of Plant Breeding

Keshav Kranthi

1比1仿制psu毕业证 宾州州立大学毕业证学位证书实拍图学历认证报告原版一模一样

Research Square (Research Square)

Dr. Sandip M Honmane

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

COMMENTS

This is chapter 15 of Environmental Economics: An Integrated Approach and it describes the pros and cons of the travel cost method of valuing environmental goods. Content may be subject to ...

The travel cost method is used to estimate economic use values associated with ecosystems or sites that are used for recreation. The method can be used to estimate the economic benefits or costs resulting from: changes in access costs for a recreational site. elimination of an existing recreational site. addition of a new recreational site.

The travel cost method estimates the economic value of recreational sites or other concentrated environmental amenities (e.g., wildlife observation) by looking at the full travel costs (time, out of pocket, and any applicable fees) of visiting the sites. In existence since a letter written in 1949 from Harold Hotelling to the director of the ...

Chapter 15. ravel Cost Method of Valuing Environmental Amenities. ent valuation or voting) or indirectly reveal values via obs. vedwillingness-to-pay for relate. useful in certain circumstances, but which has flaws f. pture use values, shedding no light on. on-use values which couldbe much larger, at least in princ.

An approach offering a methodological value to evaluate EE is the travel cost method (TCM), which is a non-market valuation approach in the field of environmental economics. Conventionally, TCM has been used to assess the economic value of recreational sites. For this study, the TCM is applied to indirectly value EE by using the costs of travel ...

Environmental and Resource Economics - The treatment of the opportunity cost of travel time in travel cost models has been an area of research interest for many decades. ... 3.3 Travel Cost Method with Consumer-Specific Values of Travel Time Savings. In this section we present the estimation results of 5 travel cost models with different ...

The travel cost model is used to value recreational uses of the environment. For example, it may be used to value the recreation loss associated with a beach closure due to an oil spill or to value the recreation gain associated with improved water quality on a river. The model is commonly applied in benefit-cost analyses and in natural ...

The travel cost method of economic valuation, travel cost analysis, or Clawson method is a revealed preference method of economic valuation used in cost-benefit analysis to calculate the value of something that cannot be obtained through market prices (i.e. national parks, beaches, ecosystems). The aim of the method is to calculate willingness to pay for a constant price facility.

The travel-cost method (TCM) is used for calculating economic values of environmental goods. Unlike the contingent valuation method, TCM can only estimate use value of an environmental good or service. It is mainly applied for determining economic values of sites that are used for recreation, such as national parks.

The travel cost model (TCM) of recreation demand is a survey-based method that was developed to estimate the recreation-based use value of natural resource systems. The TCM may be used to estimate the value of. changes in the quality of recreation sites or natural resources systems (Freeman 2003).

The Travel Cost Method (TCM) has been employed to derive the demand model, whilst the concept of consumer surplus was used for value determination and comparison. The findings showed that the ...

TCM is used to value recreational uses of the environment. It is commonly applied in benefit cost analyses (BCA) and in natural resource damage assessments. It is based on „observed behaviour‟, thus is used to estimate use values only. TCM is a demand-based model for use of a recreation site or sites. A site: a river for fishing, a trail ...

This video is a part of Conservation Strategy Fund's collection of environmental economics lessons and was made possible thanks to the support of Jon Mellber...

Keywords: Economic Value, Travel Cost Method (TCM), Recreation Area, ... Environmental economic . assessment is important as all costs and ben efits from the environment need to be .

Travel Cost Method for Environmental Valuation, Dissemination Paper-23. Center of Excellence in Environmental Economics. February 2013, Chennai, India: Madras School of Economics. pp. 10-12.

This article deals with the Travel Cost Method, which is often used in evaluating the economic value of recreational sites. This is particularly important in the coastal zone because of the level of use and the potential values that can be attached to the natural coastal and marine environment.. The Travel Cost Method (TCM) is one of the most frequently used approaches to estimating the use ...

2. The travel-cost method is of limited value if congestion is a problem. Small changes affecting recreational quality may be difficult to evaluate using this method. 3. The basic assumption of travel-cost method is that consumers treat increase in admission fees as equivalent to increase in travel cost. This is subject to question. 4.

The travel cost methods (TCM) is based on the observation that recreational services can only be realised ... Cost Benefit Analysis. Chapter 8 in Environmental and Resource Economics. An Introduction. Longman. Zandersen, M; Termansen, M and Jensen, F (2007). Evaluating approaches to predict recreation values of new forest sites. Journal of ...

The travel cost approach offers some of the most widely used demand models for valuing recreation sites. ... "The Hedonic Travel Cost Method," Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 66, No. 3, August 1984, pp. 427 ... Elizabeth A., 1980, "The Value of Time in Recreation Benefit Studies," Journal of Environmental Economics and ...

The design of this work is to estimate the recreational value and to establish functional relationship between travel cost and visitation of Lawachara National Park (LNP) in Bangladesh. This study employed zonal approach of the travel cost method. The work is grounded on a sample of 422 visitors of the LNP. Results showed that the total value ...

A common approach is the travel cost method. It assesses how much people pay to use environmental goods or places, and as a result it reveals the recreational value ... Consequently, this valuation technique may not reflect the total economic value of the environment concerned. 17 Moreover, it presents problems with respect to multi-purpose ...

In the second installment of my Env-Econ 101: Environmental Economics blog classroom data project, here is some data suitable for a single site travel cost method recreation demand model estimation. Details: n = 151. Dependent variable = trips (day trips to Wrightsville Beach, NC) Income = household income in thousands.

Issues and Limitations of the Travel Cost Method: The travel cost method assumes that people perceive and respond to changes in travel costs the same way that they would respond to changes in admission price. The most simple models assume that individuals take a trip for a single purpose ¡¦ to visit a specific recreational site.