13 Social impacts of tourism + explanations + examples

Understanding the social impacts of tourism is vital to ensuring the sustainable management of the tourism industry. There are positive social impacts of tourism, demonstrating benefits to both the local community and the tourists. There are also negative social impacts of tourism.

In this article I will explain what the most common social impacts of tourism are and how these are best managed. At the end of the post I have also included a handy reading list for anybody studying travel and tourism or for those who are interested in learning more about travel and tourism management.

The social impacts of tourism

Preserving local culture, strengthening communities, provision of social services, commercialisation of culture and art, revitalisation of culture and art, preservation of heritage, social change, globalisation and the destruction of preservation and heritage, loss of authenticity , standardisation and commercialisation, culture clashes, tourist-host relationships, increase in crime, gambling and moral behaviour, social impacts of tourism: conclusion, social impacts of tourism- further reading.

Firstly, we need to understand what is meant by the term ‘social impacts of tourism’. I have covered this in my YouTube video below!

To put it simply, social impacts of tourism are;

“The effects on host communities of direct and indirect relations with tourists , and of interaction with the tourism industry”

This is also often referred to as socio-cultural impacts.

Tourism is, at its core, an interactive service. This means that host-guest interaction is inevitable. This can have significant social/socio-cultural impacts.

These social impacts can be seen as benefits or costs (good or bad). I will explain these below.

Positive social impacts of tourism

There are many social benefits of tourism, demonstrating positive social impacts. These might include; preserving the local culture and heritage; strengthening communities; provision of social services; commercialisation of culture and art; revitalisation of customs and art forms and the preservation of heritage.

It is the local culture that the tourists are often coming to visit.

Tourists visit Beijing to learn more about the Chinese Dynasties. Tourists visit Thailand to taste authentic Thai food. Tourists travel to Brazil to go to the Rio Carnival, to mention a few…

Many destinations will make a conserved effort to preserve and protect the local culture. This often contributes to the conservation and sustainable management of natural resources, the protection of local heritage, and a renaissance of indigenous cultures, cultural arts and crafts.

In one way, this is great! Cultures are preserved and protected and globalisation is limited. BUT, I can’t help but wonder if this is always natural? We don’t walk around in Victorian corsets or smoke pipes anymore…

Our social settings have changed immensely over the years. And this is a normal part of evolution! So is it right that we should try to preserve the culture of an area for the purposes of tourism? Or should we let them grow and change, just as we do? Something to ponder on I guess…

Tourism can be a catalyst for strengthening a local community.

Events and festivals of which local residents have been the primary participants and spectators are often rejuvenated and developed in response to tourist interest. I certainly felt this was the way when I went to the Running of the Bulls festival in Pamplona, Spain. The community atmosphere and vibe were just fantastic!

The jobs created by tourism can also be a great boost for the local community. Aside from the economic impacts created by enhanced employment prospects, people with jobs are happier and more social than those without a disposable income.

Local people can also increase their influence on tourism development, as well as improve their job and earnings prospects, through tourism-related professional training and development of business and organisational skills.

Read also: Economic leakage in tourism explained

The tourism industry requires many facilities/ infrastructure to meet the needs of the tourist. This often means that many developments in an area as a result of tourism will be available for use by the locals also.

Local people often gained new roads, new sewage systems, new playgrounds, bus services etc as a result of tourism. This can provide a great boost to their quality of life and is a great example of a positive social impact of tourism.

Tourism can see rise to many commercial business, which can be a positive social impact of tourism. This helps to enhance the community spirit as people tend to have more disposable income as a result.

These businesses may also promote the local cultures and arts. Museums, shows and galleries are fantastic way to showcase the local customs and traditions of a destination. This can help to promote/ preserve local traditions.

Some destinations will encourage local cultures and arts to be revitalised. This may be in the form of museum exhibitions, in the way that restaurants and shops are decorated and in the entertainment on offer, for example.

This may help promote traditions that may have become distant.

Many tourists will visit the destination especially to see its local heritage. It is for this reason that many destinations will make every effort to preserve its heritage.

This could include putting restrictions in place or limiting tourist numbers, if necessary. This is often an example of careful tourism planning and sustainable tourism management.

This text by Hyung You Park explains the principles of heritage tourism in more detail.

Negative social impacts of tourism

Unfortunately, there are a large number of socio-cultural costs on the host communities. These negative social impacts include; social change; changing values; increased crime and gambling; changes in moral behaviour; changes in family structure and roles; problems with the tourist-host relationship and the destruction of heritage.

Social change is basically referring to changes in the way that society acts or behaves. Unfortunately, there are many changes that come about as a result of tourism that are not desirable.

There are many examples throughout the world where local populations have changed because of tourism.

Perhaps they have changed the way that they speak or the way that they dress. Perhaps they have been introduced to alcohol through the tourism industry or they have become resentful of rich tourists and turned to crime. These are just a few examples of the negative social impacts of tourism.

Read also: Business tourism explained: What, why and where

Globalisation is the way in which the world is becoming increasingly connected. We are losing our individuality and gaining a sense of ‘global being’, whereby we are more and more alike than ever before.

Globalisation is inevitable in the tourism industry because of the interaction between tourists and hosts, which typically come from different geographic and cultural backgrounds. It is this interaction that encourage us to become more alike.

Here are some examples:

- When I went on the Jungle Book tour on my travels through Goa, the tourists were giving the Goan children who lived in the area sweets. These children would never have eaten such sweets should they not have come into contact with the tourists.

- When I travelled to The Gambia I met a local worker (known as a ‘ bumster ‘) who was wearing a Manchester United football top. When I asked him about it he told me that he was given the top by a tourist who visited last year. If it was not for said tourist, he would not have this top.

- In Thailand , many workers have exchanged their traditional work of plowing the fields to work in the cities, in the tourism industry. They have learnt to speak English and to eat Western food. If it were not for the tourists they would have a different line of work, they would not speak English and they would not choose to eat burger and chips for their dinner!

Many people believe globalisation to be a bad thing. BUT, there are also some positives. Think about this…

Do you want an ‘authentic’ squat toilet in your hotel bathroom or would you rather use a Western toilet? Are you happy to eat rice and curry for breakfast as the locals would do or do you want your cornflakes? Do you want to struggle to get by when you don’t speak the local language or are you pleased to find somebody who speaks English?

When we travel, most tourists do want a sense of ‘familiar’. And globalisation helps us to get that!

You can learn more about globalisation in this post- What is globalisation? A simple explanation .

Along similar lines to globalisation is the loss of authenticity that often results from tourism.

Authenticity is essentially something that is original or unchanged. It is not fake or reproduced in any way.

The Western world believe that a tourist destination is no longer authentic when their cultural values and traditions change. But I would argue is this not natural? Is culture suppose to stay the same or it suppose to evolve throughout each generation?

Take a look at the likes of the long neck tribe in Thailand or the Maasai Tribe in Africa. These are two examples of cultures which have remained ‘unchanged’ for the sole purpose of tourism. They appear not to have changed the way that they dress, they way that they speak or the way that they act in generations, all for the purpose of tourism.

To me, however, this begs the question- is it actually authentic? In fact, is this not the exact example of what is not authentic? The rest of the world have modern electricity and iPhones, they watch TV and buy their clothes in the nearest shopping mall. But because tourists want an ‘authentic’ experience, these people have not moved on with the rest of the world, but instead have remained the same.

I think there is also an ethical discussion to be had here, but I’ll leave that for another day…

You can learn more about what is authenticity in tourism here or see some examples of staged authenticity in this post.

Read also: Environmental impacts of tourism

Similarly, destinations risk standardisation in the process of satisfying tourists’ desires for familiar facilities and experiences.

While landscape, accommodation, food and drinks, etc., must meet the tourists’ desire for the new and unfamiliar, they must at the same time not be too new or strange because few tourists are actually looking for completely new things (think again about the toilet example I have previously).

Tourists often look for recognisable facilities in an unfamiliar environment, like well-known fast-food restaurants and hotel chains. Tourist like some things to be standardised (the toilet, their breakfast, their drinks, the language spoken etc), but others to be different (dinner options, music, weather, tourist attractions etc).

Do we want everything to become ‘standardised’ though? I know I miss seeing the little independent shops that used to fill the high streets in the UK. Now it’s all chains and multinational corporations. Sure, I like Starbucks (my mug collection is coming on quite nicely!), but I also love the way that there are no Starbucks in Italy. There’s something great about trying out a traditional, yet unfamiliar coffee shop, or any independant place for that matter.

I personally think that tourism industry stakeholders should proceed with caution when it comes to ‘standardisation’. Sure, give the tourists that sense of familiar that they are looking for. But don’t dilute the culture and traditions of the destination that they are coming to visit, because if it feels too much like home….. well, maybe they will just stay at home next time? Just a little something to think about…

On a less philosophical note, another of the negative social impacts of tourism is that it can have significant consequences is culture clashes.

Because tourism involves movement of people to different geographical locations cultural clashes can take place as a result of differences in cultures, ethnic and religious groups, values, lifestyles, languages and levels of prosperity.

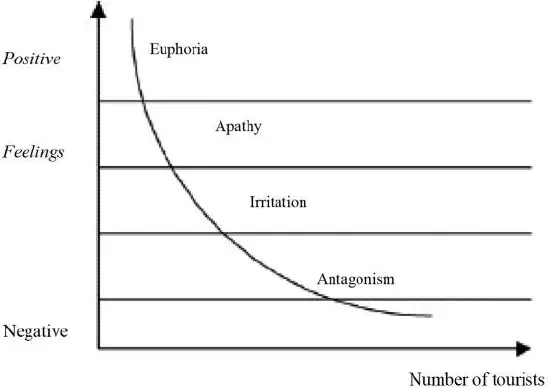

The attitude of local residents towards tourism development may unfold through the stages of euphoria, where visitors are very welcome, through apathy, irritation and potentially antagonism when anti-tourist attitudes begin to grow among local people. This is represented in Doxey’s Irritation Index, as shown below.

Culture clashes can also be exasperated by the fundamental differences in culture between the hosts and the tourists.

There is likely to be economic inequality between locals and tourists who are spending more than they usually do at home. This can cause resentment from the hosts towards the tourists, particularly when they see them wearing expensive jewellery or using plush cameras etc that they know they can’t afford themselves.

Further to this, tourists often, out of ignorance or carelessness, fail to respect local customs and moral values.

Think about it. Is it right to go topless on a beach if within the local culture it is unacceptable to show even your shoulders?

There are many examples of ways that tourists offend the local population , often unintentionally. Did you know that you should never put your back to a Buddha? Or show the sole of your feet to a Thai person? Or show romantic affection in public in the Middle East?

A little education in this respect could go a long way, but unfortunately, many travellers are completely unaware of the negative social impacts that their actions may have.

The last of the social impacts of tourism that I will discuss is crime, gambling and moral behaviour. Crime rates typically increase with the growth and urbanisation of an area and the growth of mass tourism is often accompanied by increased crime.

The presence of a large number of tourists with a lot of money to spend and often carrying valuables such as cameras and jewellery increases the attraction for criminals and brings with it activities like robbery and drug dealing.

Although tourism is not the cause of sexual exploitation, it provides easy access to it e.g. prostitution and sex tourism . Therefore, tourism can contribute to rises in the numbers of sex workers in a given area. I have seen this myself in many places including The Gambia and Thailand .

Lastly, gambling is a common occurrence as a result of tourism. Growth of casinos and other gambling facilities can encourage not only the tourists to part with their cash, but also the local population .

As I have demonstrated in this post, there are many social impacts of tourism. Whilst some impacts are positive, most unfortunately are negative impacts.

Hopefully this post on the social impacts of tourism has helped you to think carefully about the impacts that your actions may have on the local community that you are visiting. I also hope that it has encouraged some deeper thinking with regards to issues such as globalisation, authenticity and standardisation.

If you are interested in learning more about topics such as this subscribe to my newsletter ! I send out travel tips, discount coupons and some material designed to get you thinking about the wider impacts of the tourism industry (like this post)- perfect for any tourism student or keen traveller!

As you can see, the social impacts of tourism are an important consideration for all industry stakeholders. Do you have any comments on the social impacts of tourism? Leave your comments below.

If you enjoyed this article on the social impacts of tourism, I am sure that you will love these too-

- Environmental impacts of tourism

- The 3 types of travel and tourism organisations

- 150 types of tourism! The ultimate tourism glossary

- 50 fascinating facts about the travel and tourism industry

Overtourism Effects: Positive and Negative Impacts for Sustainable Development

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 02 October 2020

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Ivana Damnjanović 7

Part of the book series: Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals ((ENUNSDG))

324 Accesses

1 Citations

Responsible tourism ; Tourism overcrowding ; Tourism-phobia ; Tourist-phobia

Definitions

Tourism today is paradoxically dominated by two opposite aspects: its sustainable character and overtourism. Since its creation by Skift in 2016 (Ali 2016 ), the term “overtourism” has been a buzzword in media and academic circles, although it may only be a new word for a problem discussed over the past three decades.

Overtourism is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon destructive to tourism resources and harmful to destination communities’ well-being through overcrowding and overuse (Center for Responsible Travel 2018 ; International Ecotourism Society 2019 ) as certain locations at times cannot withstand physical, ecological, social, economic, psychological, and/or political pressures of tourism (Peeters et al. 2018 ). Overtourism is predominantly a problem producing deteriorated quality of life of local communities (Responsible Tourism n.d. ; The International Ecotourism Society 2019 ; UNWTO 2018...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Ali R (2016) ‘Exploring the coming perils of over tourism’, Skift, 23-08-2016 (online). Available at: www.skift.com (10-09-2019)

Google Scholar

Bowitz E, Ibenholt K (2009) Economic impacts of cultural heritage – research and perspectives. J Cult Herit 10(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2008.09.002

Article Google Scholar

Center for Responsible Travel – CREST (2018) The case for responsible travel: Trends & Statistics 2018. Retrieved from https://www.responsibletravel.org

Center for Responsible Travel – CREST (n.d.) Center for Responsible Travel. Retrieved 11 Sept 2019, from https://www.responsibletravel.org/

Cheer JM, Milano C, Novelli M (2019) Tourism and community resilience in the anthropocene: accentuating temporal overtourism. J Sustain Tour 27:554–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1578363

Croes R, Manuel A, Rivera KJ, Semrad KJ, Khalilzadeh J (2017) Happiness and tourism: evidence from Aruba. Retrieved from the dick pope Sr. Institute for Tourism Studies website. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.29257.85602

Epler Wood M, Milstein M, Ahamed-Broadhurst K (2019) Destinations at risk: the invisible burden of tourism. The Travel Foundation

Giulietti, S., Romagosa, F., Fons Esteve, J., & Schröder, C. (2018). Tourism and the environment: towards a reporting mechanism in Europe (ETC/ULS report |01/2018). Retrieved from European Environment Agency website: http://www.sepa.gov.rs/download/strano/ETC_TOUERM_report_2018.pdf

Global Sustainable Tourism Council – GSTC (2017) Official website. Retrieved August 23, 2019, from https://www.gstcouncil.org/

Goodwin, H. (2017) The challenge of overtourism (working paper). Responsible tourism partnership. Available at https://haroldgoodwin.info/pubs/RTP'WP4Overtourism01'2017.pdf

Interagency Visitor Use Management Council (2016) Visitor use management framework: a guide to providing sustainable outdoor recreation, 1st edn

Jordan P, Pastras P, Psarros M (2018) Managing tourism growth in Europe: the ECM toolbox. Retrieved from European Cities Marketing website: https://www.ucm.es/data/cont/media/www/pag-107272/2018-Managing%20Tourism%20Growth%20in%20Europe%20The%20ECM%20Toolbox.pdf

Kim D, Lee C, Sirgy MJ (2016) Examining the differential impact of human crowding versus spatial crowding on visitor satisfaction at a festival. J Travel Tour Mark 33(3):293–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2015.1024914

Leung Y, Spenceley A, Hvenegaard G, Buckley, R, Groves C (eds) (2018) Tourism and visitor management in protected areas: guidelines for sustainability. Best practice protected area guidelines series, vol 27. IUCN, Gland. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2018.PAG.27.en

Li L, Zhang J, Nian S, Zhang H (2017) Tourists’ perceptions of crowding, attractiveness, and satisfaction: a second-order structural model. Asia Pac J Tour Res 22(12):1250–1260. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2017.1391305

Milano C (2017) Overtourism and tourismphobia: global trends and local contexts. Retrieved from Barcelona: Ostelea School of Tourism and Hospitality website. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13463.88481

Book Google Scholar

Milano C, Novelli M, Cheer JM (2019) Overtourism and tourismphobia: a journey through four decades of tourism development, planning and local concerns. Tour Plan Dev 16(4):353–357. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1599604

Muler Gonzalez V, Coromina L, Galí N (2018) Overtourism: residents’ perceptions of tourism impact as an indicator of resident social carrying capacity – case study of a Spanish heritage town. Tour Rev 73(3):277–296. https://doi.org/10.1108/tr-08-2017-0138

Oklevik O, Gössling S, Hall CM, Steen Jacobsen JK, Grøtte IP, McCabe S (2019) Overtourism, optimisation, and destination performance indicators: a case study of activities in fjord Norway. J Sustain Tour:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1533020

Peeters P, Gössling S, Klijs J, Milano C, Novelli M, Dijkmans C, Eijgelaar E, Hartman S, Heslinga J, Isaac R, Mitas O, Moretti S, Nawijn J, Papp B, Postma A (2018) Research for TRAN committee – overtourism: impact and possible policy responses. European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels

Perkumienė D, Pranskūnienė R (2019) Overtourism: between the right to travel and residents’ rights. Sustainability 11(7):21–38. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11072138

Popp M (2012) Positive and negative urban tourist crowding: Florence, Italy. Tour Geogr 14(1):50–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2011.597421

Responsible Tourism (n.d.) Over Tourism (online). Available at: www.responsibletourismpartnership.org/overtourism

Seraphin H, Sheeran P, Pilato M (2018) Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. J Destin Mark Manag 9:374–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.01.011

Souza T, Thapa B, Rodrigues CG, Imori D (2018) Economic impacts of tourism in protected areas of Brazil. J Sustain Tour 27(6):735–749. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1408633

Spenceley A, Snyman S, Rylance A (2017) Revenue sharing from tourism in terrestrial African protected areas. J Sustain Tour 27(6):720–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1401632

The International Ecotourism Society (2019) Ecotourism is the solution to Overtourism. Retrieved 10 Sept 2019, from https://ecotourism.org/news/ecotourism-is-the-solution-to-overtourism/

The Travel Foundation. (2016). What is sustainable tourism? . Retrieved 13 July 2020, from https://www.thetravelfoundation.org.uk/resources-categories/what-is-sustainable-tourism/

Thomas, C. C., Koontz, L., and Cornachione, E. (2018). 2017 National park visitor spending effects: economic contributions to local communities, states, and the nation. Retrieved from U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service website: https://www.nps.gov/nature/customcf/NPS_Data_Visualization/docs/NPS_2017_Visitor_Spending_Effects.pdf

UN World Tourism Organization (2018a) Tourism for SDGs platform. Retrieved 13 Sept 2019, from http://tourism4sdgs.org/

UN World Tourism Organization (2018b) Measuring sustainable tourism. Retrieved from http://statistics.unwto.org/mst

UN World Tourism Organization (2018c) UNWTO tourism highlights, 2018 edition. UNWTO, Madrid, p 4. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284419876

UN World Tourism Organization; Centre of Expertise Leisure, Tourism & Hospitality; NHTV Breda University of Applied Sciences; and NHL Stenden University of Applied Sciences (2018d), ‘Overtourism’? – Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions, Executive Summary, UNWTO, Madrid. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284420070

UN World Tourism Organization (2019). ‘Key tourism figures’, infographic (online). Available at http://www2.unwto.org

UN World Tourism Organization; Centre of Expertise Leisure, Tourism & Hospitality; NHTV Breda University of Applied Sciences; and NHL Stenden University of Applied Sciences (2018) ‘Overtourism’? – understanding and managing urban tourism growth beyond perceptions, executive summary. UNWTO, Madrid. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284420070

UNEP and UNWTO (2005) Making tourism more sustainable: a guide for policy makers. World Tourism Organization Publications, Madrid

United Nations (2018) About the sustainable development goals. Retrieved 13 Sept 2019, from http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

UNWTO (2004) Tourism congestion management at natural and cultural sites. World Tourism Organization Publications, Madrid

Waller I (2011) Less law, more order. Acta Criminologica South Afr J Criminol 24(1):I–IV. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC29060

World Travel & Tourism Council (2019) Global Economic Impact & Trends 2019 (march 2019). Available at https://www.wttc.org/economic-impact/country-analysis/

World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) and McKinsey Company (2017) Coping with success: managing overcrowding in tourism destinations. Retrieved from https://www.wttc.org/-/media/files/reports/policy-research/coping-with-success%2D%2D-managing-overcrowding-in-tourism-destinations-2017.pdf

WWF – World Wide Fund For Nature (2019) Blue planet: coasts. Retrieved 12 Sept 2019, from http://wwf.panda.org/our_work/oceans/coasts/

Zehrer A, Raich F (2016) The impact of perceived crowding on customer satisfaction. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.06.007

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Health and Business Studies, Singidunum University, Valjevo, Serbia

Ivana Damnjanović

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ivana Damnjanović .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

European School of Sustainability, Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

Walter Leal Filho

Center for Neuroscience & Cell Biology, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

Anabela Marisa Azul

Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Passo Fundo University Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Passo Fundo, Brazil

Luciana Brandli

HAW Hamburg, Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

Amanda Lange Salvia

International Centre for Thriving, University of Chester, Chester, UK

Section Editor information

Department of Health Professions, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, UK

Haruna Musa Moda

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Damnjanović, I. (2020). Overtourism Effects: Positive and Negative Impacts for Sustainable Development. In: Leal Filho, W., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Wall, T. (eds) Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71059-4_112-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71059-4_112-1

Received : 10 October 2019

Accepted : 16 October 2019

Published : 02 October 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-71059-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-71059-4

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Earth and Environm. Science Reference Module Physical and Materials Science Reference Module Earth and Environmental Sciences

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: conceptual model and strategic framework

Journal of Tourism Futures

ISSN : 2055-5911

Article publication date: 15 November 2017

Issue publication date: 15 December 2017

The purpose of this paper is to clarify the mechanisms of conflict between residents and tourists and to propose a conceptual model to assess the impact of such conflicts on city tourism and to suggest a framework to develop strategies to deal with such conflicts and mitigate negative impacts.

Design/methodology/approach

Based on desk research a conceptual model was developed which describes the drivers of conflicts between residents and visitors. Building blocks of the model are visitors and their attributes, residents and their attributes, conflict mechanisms and critical encounters between residents and visitors, and indicators of the quality and quantity of tourist facilities. Subsequently the model was used to analyse the situation in Hamburg. For this analysis concentration values were calculated based on supply data of hotels and AirBnB, app-data, and expert consultations.

The study shows that in Hamburg there are two key mechanisms that stimulate conflicts: (1) the number of tourists in relation to the number of residents and its distribution in time and space; (2) the behaviour of visitors measured in the norms that they pose onto themselves and others (indecent behaviour of tourists).

Research limitations/implications

The model that was developed is a conceptual model, not a model with which hypotheses can be tested statistically. Refinement of the model needs further study.

Practical implications

Based on the outcomes of the study concrete strategies were proposed with which Hamburg could manage and control the balance of tourism.

Originality/value

City tourism has been growing in the last decades, in some cases dramatically. As a consequence, conflicts between tourists, tourism suppliers and inhabitants can occur. The rise of the so-called sharing economy has recently added an additional facet to the discussion. The ability to assess and deal with such conflicts is of importance for the way city tourism can develop in the future. This study is an attempt to contribute to the understanding of the mechanism behind and the nature of those conflicts, and the way they can be managed and controlled. Besides it illustrates how data generated by social media (apps) can be used for such purposes.

- City tourism

Conflict mechanisms

- Host-guest relations

- Overtourism

- Tourism impact studies

- Visitor management

Postma, A. and Schmuecker, D. (2017), "Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: conceptual model and strategic framework", Journal of Tourism Futures , Vol. 3 No. 2, pp. 144-156. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-04-2017-0022

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2017, Albert Postma Dirk Schmuecker

Published in the Journal of Tourism Futures. Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Introduction

Tourism is subject to massive growth. Projections made by the World Tourism Organisation anticipate a growth to 1.8 billion international arrivals worldwide till 2030. Based on its World Tourism Monitor, IPK states that city tourism is the fastest growing market segment in tourism ( IPK International, 2016 ). The direct and indirect effects of this increase in visitor numbers seem to cause an increase in annoyance among residents, which could lead to conflicts between tourists, tourism suppliers and inhabitants. The rise of the so-called sharing economy has recently added an additional facet to the discussion. During the past few years various media have reported on incidents, residents protests and the like. However, the humming-up of media may occasionally obscure the difference between actual conflicts perceived in the population and what interested actors in the media make of it. Here, only a careful analysis of the actual situation would help. On the other hand, such conflicts and the discussion about it are neither new nor limited to large cities. Yet, the focus of the discussion has shifted over the last decades: from tourism to developing countries, residents of villages in the Alps which have found themselves into ski-circuses, or greenlanders suffering from the rush of cruise ships. Recently, the discussion has shifted to where a large proportion of tourists go: from and to the European cities. Data from the German Reiseanalyse, an annual survey on holiday travel in Germany ( Schmücker et al. , 2016 ), suggest that in 2014, 31 per cent of the population and 33 per cent of German holiday makers were at home in cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants. In the cities, holiday travel is more than 80 per cent higher than in the countryside.

Tourism generates income and employment for cities, and thanks to tourism the liveliness and liveability in cities is boosted because many shops, services and facilities would not exist without that additional customer base. However, with an eye on the (social) sustainability of city tourism development, it is important to understand whether and how residents’ annoyance comes about and with which measures residents’ attitude could be kept within the margins of their tolerance level. Postma (2013) studied residents’ experiences with tourism in four tourism destinations. He identified three categories of so called “critical encounters”, four levels of annoyance, four levels on tolerance, and three levels of loyalty towards tourism development. The European Tourism Futures Research Network did a pilot study in Riga, Berlin and Amsterdam to investigate the applicability of Postma’s outcomes in an urban context. When this proved valid, the approach was used by the Dutch Centre of Expertise in Leisure, Tourism and Hospitality (CELTH) in a European study on visitor pressure in the city centres of Copenhagen, Berlin, Munich, Amsterdam, Barcelona and Lisbon. A second phase of this study just started in the Flemish cities of art (Antwerp, Bruges, Ghent, Leuven and Mechelen), Tallin and Salzburg. In this study residents were consulted to identify critical encounters and the support for various kinds of strategies to deal with it. Finally, NIT and ETFI conducted a study in Hamburg addressing these issues in 2015/2016.

The domain of tourism impact studies

The study presented here is an example of a tourism impact study. The domain of tourism impact studies has evolved since the second world war, echoing the development of tourism, its characteristics and its perception. During the first phase (1960-1970) the emphasis of tourism impact studies was on the positive economic impacts of tourism. Tourism was mainly seen as a means to strengthen economies. In the 1970s and 1980s, the focus gradually shifted to the negative social, cultural and environmental impacts. This reflected the growing concern of industrialisation, sustainability and quality of life. Ultimately in the 1980s and 1990s the interest of tourism impact studies moved to integrating the economic perspective with the social and environmental one. Tourism had continued to grow, had become more diffuse, and had become more interconnected with societies and economies. The divide in tourism impact studies between economic and social and environmental perspectives, and the emphasis on tourism and destinations as two different worlds impacting upon each other (nicely illustrated in binary terminology such as host and guest) gradually moved to a growing interest into the multidimensional relation between tourism and communities; the process by which tourism is shaped by the interactions between, tourism, host environments, economy and societies; and the meaning of tourism for society ( Postma, 2013 ; Pizam, 1978 ; Jafari, 1990, 2005, 2007 ; Butler, 2004 ; Hudson and Lowe, 2004 ; Ateljevic, 2000 ; Crouch, 1999, 2011 ; Williams, 2009 ; Sherlock, 2001 ). This so called cultural turn in tourism impact studies ( Milne and Ateljevic, 2001 ) opened the door to new research areas raising attention on themes and issues that were largely overlooked or marginalised before ( Causevic and Lynch, 2009 ), for instance, “the multiple readings of local residents while working, living, playing or, in other words, consuming and producing their localities through encounter with tourism” ( Ateljevic, 2000 , pp. 381-382).

According to Deery et al. (2012) , tourism impact studies have grown into a massive and mature field of study covering a wide spectrum of economic, social and environmental dimensions. However, Williams asserts that there is still a lack of understanding of the relationship between tourism and destination communities, both because the number of empirical studies, inconclusive or conflicting results of empirical studies, and a contested conceptual basis ( Williams, 2009 ). Postma (2013) confirms that mainstream tourism impact literature does not offer useful theoretical frameworks for tourism impact studies that focus on the tourism community relations.

Sustainable tourism

Although the notion of sustainable development has led to considerable debate since its introduction which in part is due to its vagueness for concrete action, it is incorporated as an important starting point in contemporary policy and planning worldwide. This also applies to tourism, where the basic ideas of sustainable development were gradually translated into the concept of sustainable tourism development. The first ideas were introduced by Krippendorf (1984) , and they were elaborated in the Brundtland report ( World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987 ) and the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. The ideas presented in the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development and in Agenda 21 guided the World Conference on Sustainable Tourism in Lanzarote in 1995, where the core principles were established ( France, 1997 ; Martin, 1995 ). In line with sustainable development, sustainable tourism development tries to establish a suitable balance between economic, environmental and social aspects of tourism development to guarantee its long-term sustainability ( World Tourism Organisation, 2004 ). The World Tourism Organisation’s core principles of sustainable tourism development are: to improve the quality of life of the host community; to provide high quality experience for visitors; and to maintain the quality of the environment, on which both the host community and the visitors depend ( Mill and Morrison, 2002 ).

Sustainable development and sustainable tourism development do not aim at prosperity and material gains but primarily at well-being and quality of life ( Postma, 2001, 2003 ; Postma and Schilder, 2007 ; Jackson, 1989 ; Burns, 1999 ). In this view residents should be both the starting point and the checkpoint for tourism policy and planning. As the negative perception of tourism affects the way in which residents perceive their quality of community life ( Kim, 2002 ), the long-term sustainability of tourism might be negatively affected by any impacts from tourism causing irritation, annoyance, or anger among local residents. The threshold level at which enthusiasm and support for tourism turns into irritation could be regarded as an indicator of the edge of sustainable development. Therefore, sustainable tourism development requires both greater efforts to incorporate the input of residents in the planning process both in communities exposed to tourism for the first time and in established destinations experiencing increased volumes of tourists ( Burns and Holden, 1997 ; Harrill, 2004 ), as well as to studying host community attitudes and the antecedents of residents’ reactions ( Zhang et al. , 2006 ). As Haywood (1988) states: “Local governments should be more responsible to the local citizens whose lives and communities may be affected by tourism in all its positive and negative manifestations” (in Burns and Holden, 1997 ).

Thus, understanding current and potential conflicts between residents and tourists is an integral part of the sustainable tourism debate. By definition, sustainable tourism development does have an ecological, economic and social dimension. It may be argued that the inclusion of the needs of the inhabitants stimulates the traditional understanding of a tourism market between buyers and sellers: while consumers look for tourism experiences and providers look for business opportunities, the claims of residents are more extensively focussed on an adequate quality of life ( Postma, 2003 ). The larger the interfaces between these three stakeholder groups, the more conflict-free tourism will be able to develop ( Figure 1 ).

For (city) tourism, it seems advisable to define the concept of sustainability in a broad and comprehensive way. Sustainable tourism thus entails “acceptance by the population”, and the population is clearly a part of the social dimension. The participation of the population and securing/increasing the acceptance of tourism is therefore also one of the objectives for Hamburg’s sustainable tourism development. To develop tourism in a sustainable way, in Hamburg as in other cities, the challenge is to bring the quality of life demands of the inhabitants (social dimension) and the quality-of-opportunity requirements of the providers (economic dimension) as far as possible into line.

The case of Hamburg

The aim of this viewpoint paper is to contribute to the conceptualisation of tourism community relations and to clarify the mechanisms of conflict between residents and tourists and to propose a conceptual model to assess the impact of such conflicts on city tourism and to suggest a framework to develop strategies to deal with such conflicts and mitigate negative impacts. This model was developed for a study in Hamburg that addressed the balanced and sustainable growth of tourism in the city. Hamburg is one of the most popular city destinations in Germany. The city, located in the north of the country, is faced with a gradual increase of visitor numbers, especially during the past few years. Internal papers of Hamburg’s Destination Management Organisation, Hamburg Tourismus ( HHT, 2015 ), show that between 2001 and 2015, the number of overnight stays in Hamburg increased with over 150 per cent, which is more than, for example, Barcelona (+112 per cent), Venice (+120 per cent), Amsterdam (+54 per cent) and Berlin (+153 per cent). Although the negative implications of tourism are not as visible as in some other European cities, critiques are getting louder in selected parts of the city, as shown by a regular resident monitoring implemented by HHT. Strategies to distribute tourism flows in time and space could help to prevent or to counteract. The study, commissioned by HHT, is an attempt to contribute to the understanding of the mechanisms behind and the nature of possible conflicts between tourists, tourism suppliers and residents and the way they can be managed and controlled, for example, by making use of data generated by social media. Based on desk research, a conceptual model was developed which describes the drivers of conflict between residents and visitors. Building blocks of the model are visitors and their attributes, residents and their attributes, conflict mechanisms and areas of conflict between both parties, and indicators of quality and quantity of tourist facilities. Subsequently the model was used to analyse the situation in Hamburg.

Conflict drivers and irritation factors

To develop a better understanding of the mechanism of conflict between tourists, tourism suppliers and residents, desk research was conducted into potential areas of conflict between locals and tourists, which factors would characterize particularly vulnerable residents and particularly disturbing locals, and what would be strategic options to manage and control the (occurrence) of such conflicts.

There is danger that for a focus on only negative aspects in the interaction between tourists and locals would cause bias. Therefore, it should be stressed that – for the destination – tourism is not an end in itself, but primarily an economic and, second, a social potential. Economically, tourism usually has positive effects for the inhabitants, mainly through the money flowing in from the outside, which tourists spend in the city and for the city. This money leads to tourist turnover, which is reflected in income. This income can be in the form of salaries, income from self-employment, company profits, or from the leasing or sale of land, buildings or flats. Indirectly, tourism revenues also contribute to the creation and maintenance of infrastructures and (tourist) offers which can also be used by residents. This applies to most cultural institutions (from the opera to the zoo), but also for public transport offers, gastronomy, etc. Socially, tourism can lead to desirable effects in the destination as well. This includes the (simple) encounter with others (provided they are “encounters on eye”), a general stimulation and a social enrichment and liveliness of the city.

It is especially in the economic dimension, where the dilemma to which involvement with tourism could sometimes lead, becomes clear. If an apartment is rented as a holiday home rather than as a permanent living space, because the landlord will get a higher income (in some cases at lower costs and lower risk), this is undoubtedly disadvantageous for the regular tenants and land-lords of houses undoubtedly advantageous. An assessment of this dilemma is therefore not only possible based on (short-term) economic considerations, but must consider long-term and non-economic aspects. The understanding of such balancing processes and the existence of potentially positive and negative effects of tourism is fundamental to the overall further consideration.

The study of the interaction between tourists and the residents of the destination has already shown a longer academic tradition (see Harrill, 2004 ; Zhang et al. , 2006 ; Andereck et al. , 2005 ; Vargas-Sánchez et al. , 2008 ). However, Postma notes: “A review of the literature concerning residents’ attitude toward tourism revealed an absence of research exploring factors that specifically contribute or cause irritation development, with the exception of Doxey’s (1975) article and the authors who quote him or elaborated and described his model in more detail, such as Murphy (1985) , Fridgen (1991) , Ryan (1991) , Matthieson and Wall (1982) , Wall and Mathieson (2006) , Vanderwerf (2008) and Milligan (1989) . Based on empirical investigations he designed an irritation index, describing four stages in the development of irritation: euphoria, apathy, annoyance, and antagonism. The model of this “irridex” describes the changing attitude of residents ensuing from reciprocal impacts between tourists and residents and varying degrees of compatibility between the residents and outsiders. According to Doxey (1975) irritation differs from person to person: it is affected by various personal characteristics and various characteristics of the tourist destination.

Much literature is devoted to investigating the positive and negative impacts of tourism. Rátz and Puczkó (2002) have summarised these impacts. This overview indicates that irritation might develop along four dimensions: population impacts, transformation of the labour market, changes in community characteristics and community structure, impacts at the individual and family level, and impacts on the natural and cultural resources ( Postma, 2013 , p. 25) lists the socio-cultural impacts of tourism, which is the focus of this study.

Model construction

The results of the desk research were put together in a conceptual framework to conceptualise the complex issue under study, that has largely been unexplored in this way so far. The model helps to identify and visualise possible irritation points on the part of the inhabitants and their (possibly disturbing) interaction with visitors. Just like other models, this conceptual model is a schematic abstraction of reality. It takes individual, relevant aspects into account, while other aspects might be neglected. The intention is not to be complete, but to visualise reality and identify relevant issues. So, the model presented here is abstract and descriptive. It is not a scientific structure or measurement model from which statistical hypotheses can be derived, but rather a “thinking structure” for further investigation.

The overview of positive and negative possible effects of tourism on the social dimension of tourism by Rátz and Puczkó (2002) is a first starting point for the modelling process. A second starting point is the Tourist Destination Model as developed by NIT, which has been evolved throughout many years ( Schmücker, 2011 ). Further starting points for the modelling process were reports and survey results from cities in which there have already been clearly observed annoyances among the local population because of tourism. A particularly prominent example is Barcelona (even a film was recorded), but also cities like Venice, Vienna, Amsterdam or Berlin are not only reported in the local, national and international press.

For the elaboration of a conceptual model, it is first necessary to clarify which content should be taken into account. First, the key actors: tourists and their characteristics, and residents and their characteristics. Second, attributes of the tourist product because their quantity and quality of the tourism opportunity spectrum are the prerequisite for tourists to visit the city at all. This includes both the specific tourist offer (hotel industry, semi-professional, private and sharing offers, MICE offers) as well as the offers which are aimed at both tourists and locals (cultural offers, gastronomy, mobility, etc.).

With these building blocks, the essential conflict mechanisms and concrete fields of conflict can be described, as well as strategic courses of action against the objectives of sustainable tourism development. The model is displayed in Figure 2 .

The model shows the interaction between local residents and tourists, its conditions and consequences. Conditioned by the attributes of both parties, and of conflict mechanisms between the two (sensitivity to) areas of conflict do arise. The model helps to understand how this process works. Based on intensive data collection and data analysis the model was applied in Hamburg to make an analysis of the distribution in time and space of overnight stay accommodation, events and visitor flows, the annoyance tourism caused among local residents, and the strategies that could be taken to manage tourism flows in a sustainable way. In the following sections the components of the model will be described in detail.

Relevant characteristics of tourists

“Adaptivity”: the ability of tourists to adapt to the people in the destination and their habits. “Adaptive” behaviour can be divided into general and specific. General adaptive behaviour is at work in many cultures, for example, general friendliness and restraint. Specific adaptive behaviour can include behaviour accepted by some cultures, but by others (e.g. preparing food in the hotel room or visiting sacred buildings with/without head cover). The larger the cultural distance between the locals and the tourists, the greater their adaptiveness should be to avoid conflicts.

“Tourism culture”: it seems plausible to attribute a greater potential for irritation to tourists with certain behaviours, travel situations or group sizes than others. In particular tourist trips that are mainly aimed at enjoyment in the city. Eye-catching examples can be actions such as bachelor parties, visits to sporting events and the like. In connection with conspicuous behaviour (e.g. shouting, drinking, etc.) the irritation potential increases significantly. This behaviour is often different from home. “[It] can be labelled as a tourist culture, a subset of behavioural patterns and values that tend to emerge only when the visitors are travelling but which, when viewed by local people in receiving areas, project a false and misleading image of the visitors and the societies they represent” ( Postma, 2013 , p. 144). Group size belongs to the same category: it can be assumed that tourists coming in (large) groups, tend to generate irritation easier than individual tourists.

Other demographic, socio-cultural and personal characteristics: of course there are other characteristics of tourists that could cause irritation or annoyance. However, it seems plausible to consider, for example, purely demographic attributes (such as age, gender, household type and size) as background variables rather than primary features in the model. The same applies to other attributes that contribute to the adaptivity, to socio-cultural attributes (nationality, ethnicity, language, attitude to women), to socio-economic attributes (such as income and consumption patterns) and to the regional origin of the visitors. Regardless of the adaptivity, the regional origin can be a relevant driver of irritation. Even if tourists behave in a very friendly and reserved manner, their appearance may be irritating some inhabitants due to specific characteristics (such as skin colour, language/dialect or clothing). Even if there is no objective cause for complaint, strangeness as such can cause irritation.

It is important to emphasise that these background variables are not directly affecting behaviour in a direct way. Stephen Williams (2009 , p. 144) comments: “The behaviour patterns of visitors often divert from their socio-cultural norms and do not accurately represent the host societies from which they originate, with conspicuous increases in levels of expenditure and consumption, or adoption of activities that might be on the margins pf social acceptability at home (e.g. drinking, overeating, gambling, atypical dress codes, nudity, semi nudity)”.

Relevant characteristics of inhabitants

On the part of the inhabitants, a fairly large number of potential attributes can be identified in the literature which could influence their attitude towards the tourists.

demographic characteristics: gender, age, education;

socio-economic characteristics: employment and income situation, housing situation (place of residence, duration of residence, property/rented), personal relationship to the city/district, attitude to economic growth;

socio-psychological and socio-cultural characteristics: orientation (new vs traditional) and lifestyle, origin (born and raised or migrant, born in city or country), personality traits such as self-image and group identity; and

tourism-specific characteristics: knowledge about tourism and its effects, income dependence from tourism, spatial distance to tourist hotspots and actual contacts with tourists, involvement in decisions about tourism development.

Harrill (2004) , Zhang et al. (2006) , Andereck et al. (2005) , Vargas-Sánchez et al. (2008) , Faulkner and Tideswell (1997) .

Investigations into residents’ perceptions of tourism have been approached from several perspectives: the balance between positive and negative perceived impacts (social exchange theory), the shared social representations of tourism with other community members (social representations theory; Moscovici, 1981, 1983, 1984, 1988 ), the speed and intensity of tourism growth, especially in the early phases of tourism development (social disruption theory; England and Albrecht, 1984 ; Kang, Long and Perdue, 1996 ) and increasing investments and associated commodification and destruction of the landscape and idyll (theory of creative destruction ( Mitchell, 1998 )).

“Cultural Distance” as a collective term for the cultural difference between tourists and locals. It can take the form of a lack of adaptivity, appearance in (large) groups, disturbing behaviour on the part of the tourists, and a sensitivity on the part of the local (which has its roots in the factors mentioned above) Altogether, cultural distance can be understood as the socio-cultural difference between locals and tourists. The term goes back to Stephen Williams (2009) : the larger the cultural distance, the greater the potential for conflict.

Spatial and temporal distribution. This refers to the crowding (the sheer number of tourists) or the concentration of tourists in space and/or time. This crowding can lead to irritation irrespective of “cultural distance”: even with the highest degree of “correct behaviour” by highly adaptive individual tourists without further disturbing characteristics, crowding can occur.

Each aspect can potentially cause irritation on its own, but in combination the effects become potentially stronger.

Concrete fields of conflict

The components of the model described in the previous section point at conflicts in a more abstract way (which characteristics and features could lead to conflicts and how does this work in general?). This section will focus on the actual (concrete) conflict fields that can occur. The basis for the collection of these fields of conflict is derived from the illustrated antecedents, yet it is mainly about what has been reported by destinations (especially big cities) and survey results.

The numerous arguments, which are mentioned in the literature, but above all in reports and interviews on areas of conflict, can be divided into possible direct restrictions (those which are perceived at the moment of occurrence) and indirect consequences. Table I shows the concrete fields of conflict that were identified in an overview. The fields of conflict are characterised as “potential”, because it is a structured collection without any further statement as to whether and how far these are relevant to Hamburg. Moreover, it is not an overview of fears by the authors, but about fears of local residents as they experienced in their daily lives (e.g. the authors do not believe that the employment of people with an immigration background is a negative consequence of tourism).

It becomes clear that the number of possible conflict fields is large and their structure heterogeneous and not always clearly assignable. In addition, specific developments do not only impact upon the direct interests of the local residents, but also upon the relations between different tourist actors and economic groups. For example, it is not clear yet how the renting through sharing portals has an impact upon the price development in the hotel industry ( Zervas et al. , 2016 ), and how much “sharing” (as opposed to businesses) there really is in the sharing economy ( O’Neill and Ouyang, 2016 ; European Commission, 2016 ).

In the case of Hamburg, conflicts arose from both temporary or seasonal and permanent sources of conflict. Examples of temporary sources of conflict can be large events, but also groups of cruise passengers who flood the city during daytime in the summer season. In the Hamburg case, there are few very large events in the course of the year which can be conflicting with the interests of the inhabitants, although mitigation and management measures have been taken. But also, a permanent area of conflict can be found in the concrete case, e.g. the misbehaviour of groups of drunken or otherwise intoxicated young males (mostly), entering the red-light district around Reeperbahn.

Strategic approaches

For the residents: to secure and increase the acceptance of tourism.

For tourists and touristic providers: to secure and increase tourist value creation.

Against this background, it is important to ask which measures are appropriate to achieve these goals (see also Figure 1 ).

Although this project is primarily aimed at the equalisation of tourism flows, further strategies and actions are conceivable that mitigate the perceived negative effects of tourism.

improved spatial distribution of visitors (Spreading visitors around the city and beyond);

better time distribution of visitors (time-based rerouting);

regulation (regulation);

incentives through creating itineraries;

improved audience segmentation (visitor segmentation);

making the benefit of the inhabitants clearer (make residents benefit from the visitor economy);

tourist offers with benefits for the inhabitants (create city experiences);

communicating with and involving local stakeholders;

communication approaches towards visitors (communicating with and involving visitors); and

improvement of infrastructure (Improve city infrastructure and facilities).

Each of those strategies is linked to specific actions (CELTH, 2016).

Conclusions and discussion

Currently tourism is on the rise and city tourism has a large share in this increase. The UN World Tourism Organisation anticipates a further growth during the years to come. Emerging economies play a major role in the vast increase of tourism. Driven by an increase of wealth the middle classes in these economies are discovering the world and for example, in Europe it is evident that this is causing a growing level of annoyance among residents of (urban) destinations. Because of the rise of international tourism it is likely that the situation will worsen if visitor flows are not managed properly. This requires a thorough understanding of the forces, the conditions and mechanisms at work. This paper is an attempt to contribute to this understanding by means of a case study in Hamburg and the construction of a model that could help to manage visitor flows and anticipate possible effects of potential measures. Future studies are needed to refine the model.

The model developed in this paper is a conceptual model. It is based upon desk research on and expert interviews in various European cities and a literature review. As a conceptual model, it’s main value lies in sorting and arranging the many possible aspects of visitor pressure occurring in city tourism. It can be (and in the case of Hamburg has been) used as a working structure to assess possible fields of conflict arising from the conflict mechanisms contained in the model. Furthermore, it is intended to help clarify the relation between stakeholders (i. e. the residents, the tourism suppliers and the visitors) and their respective objectives. Being conceptual, however, it is not intended to serve as a structural model delivering graphical representations of hypotheses or structural relationships.

Obviously, in order to assess the situation in a specific destination, the conceptual model is only one basic tool. For concrete applications, two more steps need to be taken, building on the model.

First, the concrete fields of conflict have to be identified. These fields will differ in their importance from city to city and from destination to destination. While in one city, cruise tourists flooding the city centre impose problems, it might be stag parties or beer bikes in another destination and the rise of housing prices because of increasing numbers of Airbnbs in the next. Typically, public discussion about “visitor pressure” or “overtourism” starts with one publicly visible field of conflict. The conceptual model can then help to embed this problem into a larger framework and thus prevent it from being discussed in isolation. In other cases, cities want to assess their current status and vulnerability to unbalanced tourism development. Then, the conceptual model can help to get a more holistic view to the problem.

Second, indicators and metrics have to be applied to the concrete fields of conflict. If, e.g. crowding is identified as a field of conflict, then indicators and measurement for crowding need to be found. These can be visitor counts or usage data from apps and mobile phones. If shared accommodation seems to be the problem, then the number of hosts, listings and overnights at Airbnb and other platforms can be appropriate metrics. A major drawback, however, in the current situation seems to be the lack of comparable metrics. Each city and destination has to rely on its own assessment of “how much is too much”. In terms of overnight stays in hotels, a reasonably well maintained European database exists (TourMIS). Furthermore, some methodological approaches to assess some fields of visitor pressure have been published by McElroy (2006) or Boley et al. (2014) . However, comparable indicators and metrics specific for the field of visitor pressure are not at hand at the moment.

Third, taking action and implementing measures is a logical consequence in cases where the assessment phase has shown problems of visitor pressure. These actions might be in the fields of regulation, visitor management, pricing or communication. The model does not give suggestions as to which actions to take. It can work, however, as a guideline for the strategic objectives of such actions, namely to secure (and possibly increase) the economic value from tourism for the city and its tourism suppliers on the one hand and to secure (and possibly increase) tourism acceptance on the residents’ side on the other hand.

Quality of life: equal demands on tourism

Conceptual model of conflict drivers and irritation factors

Potential areas of conflict

Source: Adapted from Postma (2013)

Andereck , K.L. , Valentine , K.M. , Knopf , R.C. and Vogt , C.A. ( 2005 ), “ Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 32 No. 4 , pp. 1056 - 76 .

Ateljevic , I. ( 2000 ), “ Circuits of tourism: stepping beyond the ‘production/consumption’ dichotomy ”, Tourism Geographies , Vol. 2 No. 4 , pp. 369 - 88 .

Boley , B.B. , McGehee , N.G. , Perdue , R.R. and Long , P. ( 2014 ), “ Empowerment and resident attitudes toward tourism: strengthening the theoretical foundation through a Weberian lens ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 49 , pp. 33 - 50 , available at: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.08.005

Burns , P. ( 1999 ), An Introduction to Tourism and Anthropology , Routledge , London .

Burns , P.M. and Holden , A. ( 1997 ), “ Alternative and sustainable tourism development – the way forward? ”, in France , L. (Ed.), The Earthscan Reader in Sustainable Tourism , Earthscan Publications Ltd , London , pp. 26 - 8 .

Butler , R. ( 2004 ), “ Geographical research on tourism, recreation and leisure: origins, eras and directions ”, Tourism Geographies , Vol. 6 No. 2 , pp. 143 - 62 .

Causevic , S. and Lynch , P. ( 2009 ), “ Hospitality as a human phenomenon: host-guest relationships in a post-conflict setting ”, Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development , Vol. 6 No. 2 , pp. 121 - 32 .

Crouch , D. (Ed.) ( 1999 ), Leisure/Tourism Geographies: Practices and Geographical Knowledge , Routledge , London .

Crouch , D. ( 2011 ), “ Tourism, performance and the everyday ”, Leisure Studies , Vol. 30 No. 3 , pp. 378 - 80 .

Deery , M. , Jago , L. and Fredline , L. ( 2012 ), “ Rethinking social impacts of tourism research: a new research agenda ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 33 , pp. 64 - 73 .

Doxey , G.V. ( 1975 , 8-11 September), “ A causation theory of visitor-resident irritants: methodology and research inferences ”, Proceedings of the Travel Research Association, ‘The impact of tourism’, 6th Annual Conference , San Diego, CA , pp. 196 - 8 .

England , J.L. and Albrecht , S.L. ( 1984 ), “ Boomtown and social disruption ”, Rural Sociology , Vol. 49 , pp. 230 - 46 .

European Commission ( 2016 ), “ A European agenda for the collaborative economy ”, COM(2016) 356 final and the Staff Working Document (SWD(2016)) 184 final .

Faulkner , B. and Tideswell , C. ( 1997 ), “ A framework for monitoring community impacts of tourism ”, Journal of Sustainable Tourism , Vol. 5 No. 1 , pp. 3 - 28 .

France , L. ( 1997 ), “ Introduction ”, in France , L. (Ed.), The Earthscan Reader in Sustainable Tourism , Earthscan Publications Ltd , London , pp. 1 - 22 .

Fridgen , J. ( 1991 ), Dimensions of Tourism , American Hotel and Motel Association Educational Institute , East Lansing, MI .

Harrill , R. ( 2004 ), “ Residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: a literature review with implications for tourism planning ”, Journal of Planning Literature , Vol. 18 No. 3 , pp. 251 - 66 .

Haywood , K.M. ( 1988 ), “ Responsible and responsive tourism planning in the community ”, Tourism Management , Vol. 9 , pp. 105 - 18 .

HHT ( 2015 ), Wirtschaftsfaktor Tourismus. Hamburg und die Metropolregion , dwif-Consulting GmbH, München/Berlin , Datengrundlage .

Hudson , J. and Lowe , S. ( 2004 ), Understanding the Policy Process. Analysing Welfare Policy and Practice , 2nd ed. , The Policy Press , Bristol .

IPK International ( 2016 ), “ ITB world travel trends report 2015-2015 ”, Messe Berlin GmbH, Berlin .

Jackson , E.L. ( 1989 ), “ Environmental attitudes, values and recreation ”, in Jackson , E.L. and Burton , T.L. (Eds), Understanding Leisure and Recreation. Mapping the Past, Charting the Future , E&F Spon Ltd , London , pp. 357 - 83 .

Jafari , J. ( 1990 ), “ Research and scholarship. The basis of tourism education ”, The Journal of Tourism Studies , Vol. 1 No. 1 , pp. 33 - 41 .

Jafari , J. ( 2005 ), “ Bridging out, nesting afield: powering a new platform ”, Journal of Tourism Studies , Vol. 16 No. 2 , pp. 1 - 5 .

Jafari , J. ( 2007 ), “ Entry into a new field of study: leaving a footprint ”, in Nash , D. (Ed.), The Study of Tourism: Anthropological and Sociological Beginnings , Elsevier , Oxford , pp. 108 - 21 .

Kang , Y.-S. , Long , P.T. and Perdue , R.R. ( 1996 ), “ Resident attitudes toward legal gambling ”, Annals of Tourism Research , Vol. 23 No. 1 , pp. 71 - 85 .

Kim , K. ( 2002 ), “ The effects of tourism impacts upon quality of life of residents in the community ”, PhD thesis, Electronic Theses and Dissertations at Virginia Tech, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, available at: http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/theses/available/etd-12062002-123337/unrestricted/Title_and_Text.pdf

Koens , K. and Postma , A. ( 2016 ), Understanding and Managing Visitor Pressure in Urban Tourism. A Study into the Nature and Methods used to Manage Visitor Pressure in Six Major European Cities , CELTH , Leeuwarden/Breda/Vlissingen .

Krippendorf , J. ( 1984 ), The Holidaymakers. Understanding the Impact of Leisure and Travel , Heinemann , London .

McElroy , J.L. ( 2006 ), “ Small Island tourism economies across the lifecycle ”, Asia Pacific Viewpoint , Vol. 47 No. 1 , pp. 61 - 77 .

Martin , C. ( 1995 ), “ Charter for sustainable tourism. World Conference on Sustainable Tourism ”, Lanzarote, 27-28 April, available at: www.world-tourism.org/sustainable/doc/Lanz-en.pdf

Matthieson , A. and Wall , G. ( 1982 ), Tourism: Economic, Physical and Social Impacts , Longman , Harlow .

Mill , R.C. and Morrison , A.M. ( 2002 ), The Tourism System , 4th ed. , Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company , Dubuque, IA .

Milligan , J. ( 1989 ), “ Migrant workers in the Guernsey hotel industry ”, PhD thesis, Nottingham Business School, Nottingham .

Milne , S. and Ateljevic , I. ( 2001 ), “ Tourism, economic development and the global-local nexus: theory embracing complexity ”, Tourism Geographies , Vol. 3 No. 4 , pp. 369 - 93 .

Mitchell , C.J.A. ( 1998 ), “ Entrepreneurialism, commodification and creative destruction: a model of post-modern community development ”, Journal of Rural Studies , Vol. 14 , pp. 273 - 86 .

Moscovici , S. ( 1981 ), “ On social representations ”, in Forgas , J.P. (Ed.), Social Cognition: Perspectives on Everyday Understanding , Academic Press , London , pp. 181 - 209 .

Moscovici , S. ( 1983 ), “ The coming era of social representations ”, in Codol , J.P. and Leyens , J.P. (Eds), Cognitive Approaches to Social Behaviour , Nijhoff , The Hague , pp. 115 - 50 .

Moscovici , S. ( 1984 ), “ The phenomenon of social representations ”, in Farr , R.M. and Moscovici , S. (Eds), Social Representations , Cambridge University Press , Cambridge , pp. 3 - 70 .

Moscovici , S. ( 1988 ), “ Notes toward a description of social representations ”, European Journal of Psychology , Vol. 18 , pp. 211 - 50 .

Murphy , P.E. ( 1985 ), Tourism: A Community Approach , Methuen , London .

O’Neill , J.W. and Ouyang , Y. ( 2016 ), “ From air mattresses to unregulated business: an analysis of the other Side of Airbnb ”, Penn State University School of Hospitality Management, State College, PA .

Pizam , A. ( 1978 ), “ Tourism impacts: the social costs to the destination community as perceived by its residents ”, Journal of Travel Research , Vol. 16 No. 4 , pp. 8 - 12 .

Postma , A. ( 2001 ), “ An approach for integrated development of quality tourism ”, in Andrews , S. , Flanagan , S. and Ruddy , J. (Eds), Tourism Destination Planning: Proceedings of ATLAS 10th Anniversary International Conference Tourism, Innovation and Regional Development, held in Dublin , Vol. 2 , DIT , Dublin , 3-5 October , pp. 205 - 17 .

Postma , A. ( 2003 ), “ Quality of life, competing value perspectives in leisure and tourism ”, Keynote presentation, ATLAS 10th International Conference, “Quality of Life, competing value perspectives in leisure and tourism” , Leeuwarden , June .

Postma , A. ( 2013 ), “ ‘When the tourists flew in’. Critical encounters in the development of tourism ”, PhD thesis, Faculty of Spatial Sciences, University of Groningen, Groningen .

Postma , A. and Schilder , A.K. ( 2007 ), “ Critical Impacts of tourism; the case of Schiermonnikoog ”, in Casado-Diaz , M. , Everett , S. and Wilson , J. (Eds), Social and Cultural Change: Making Space(s) for Leisure and Tourism , Leisure Studies Association publication , Vol. 98, No. 3 , University of Brighton , Eastborne , pp. 131 - 50 .

Rátz , T. and Puczkó , L. ( 2002 ), The Impacts of Tourism: An Introduction , Hame Polytechnic , Hämeenlinna .

Ryan , C. ( 1991 ), Recreational Tourism , Routledge , London .

Schmücker , D. , Grimm , B. and Beer , H. ( 2016 ), “ Reiseanalyse 2016 ”, in Schrader , R. (Ed.), Summary of the Findings of the RA 2016 German Holiday Survey , FUR , Kiel , pp. 7 - 8 .

Schmücker , D. ( 2011 ), Einflussanalyse Tourismus: Einfluss einer Festen Fehmarnbeltquerung auf den Tourismus in Fehmarn und Großenbrode , NIT , Kiel .

Sherlock , K. ( 2001 ), “ Revisiting the concept of hosts and guests ”, Tourist Studies , Vol. 1 No. 3 , pp. 271 - 95 .

Vanderwerf , J. ( 2008 ), “ Creative destruction and rural tourism planning: the case of Creemore, Ontario ”, master thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, available at: http://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/handle/10012/3809 (accessed 17 June 2009 ).

Vargas-Sánchez , A. , De los Angeles Plaza-Meija , M. and Porras-Bueno , N. ( 2008 ), “ Understanding residents’ attitudes toward the development of industrial tourism in a former mining community ”, Journal of Travel Research , Vol. 47 No. 3 , pp. 373 - 87 .

Wall , G. and Mathieson , A. ( 2006 ), Tourism: Changes, Impacts, and Opportunities , Pearson Education Unlimited , Essex .

Williams , S.W. ( 2009 ), Tourism Geography: A new Synthesis , 2nd ed. , Routledge , New York, NY .

World Commission on Environment and Development ( 1987 ), Our Common Future , Oxford University Press , Oxford , available at: http://worldinbalance.net/intagreements/1987-brundtland.pdf, www.un-documents.net/wced-ocf.htm (accessed 15 May 2005 ).

World Tourism Organisation ( 2004 ), “ Sustainable development of tourism. Concepts and definitions ”, available at: www.world-tourism.org/sustainable/top/concepts.html (accessed 15 May 2005 ).

Zervas , G. , Proserpio , D. and Byers , J. ( 2016 ), “ The rise of the sharing economy: estimating the impact of Airbnb on the hotel industry ”, Research Paper No. 2013-16, Boston University School of Management, Boston .

Zhang , J. , Inbakaran , J. and Jackson , M.S. ( 2006 ), “ Understanding community attitudes toward tourism and host-guest interaction in the urban-rural border region ”, Tourism Geographies , Vol. 8 No. 2 , pp. 182 - 204 .

Acknowledgements

© Albert Postma and Dirk Schmuecker. Published in the Journal of Tourism Futures . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

Corresponding author

About the authors.

Albert Postma is a Professor of Applied Sciences at the European Tourism Futures Institute, Stenden University of Applied Sciences, Leeuwarden, The Netherlands.

Dirk Schmuecker is the Head of Research at the NIT Institute for Tourism Research in Northern Europe, Kiel, Germany.

Related articles

All feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

- Conferences

- Current Issue

- Back Issues

- Announcements

- Full List of Journals

- Migrate a Journal

- Special Issue Service

- Conference Publishing

- Editorial Board

- OPEN ACCESS Policy

- Other Journals

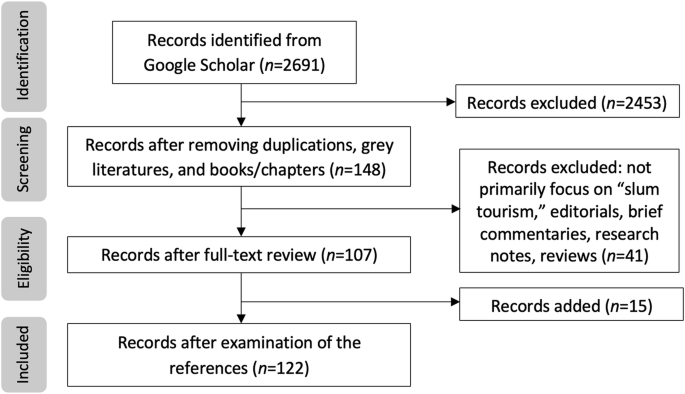

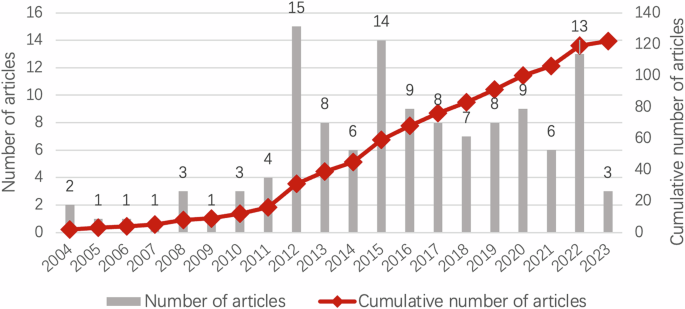

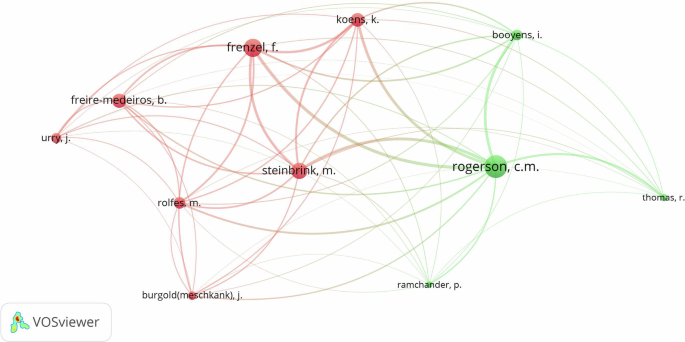

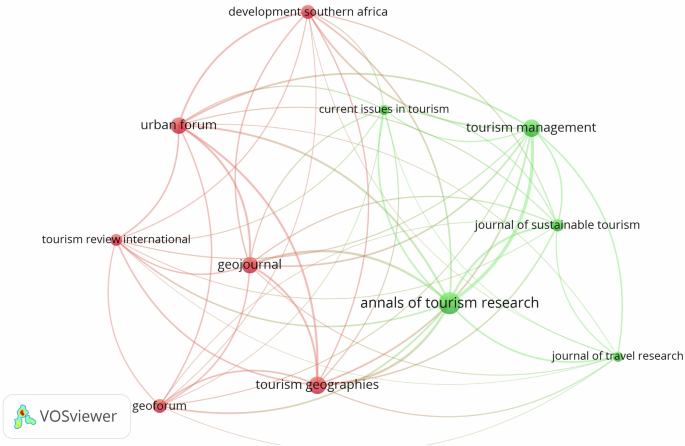

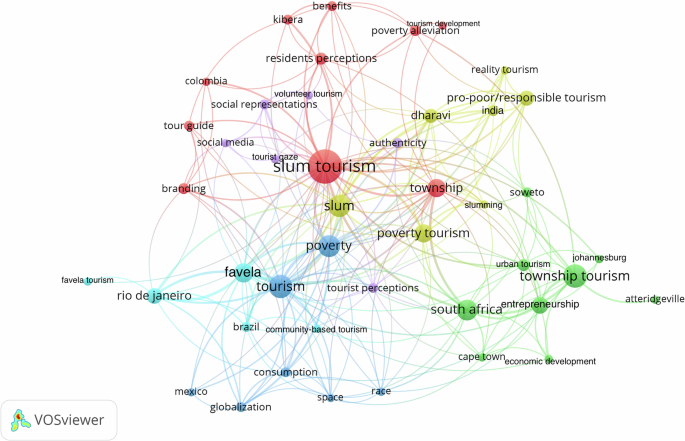

Positive and Negative Impacts of Tourism on Culture: A Critical Review of Examples from the Contemporary Literature