- Introduction

- Palp/Percus

- Auscultation

Palpation/Percussion

Thoracic expansion:.

- Is used to evaluate the symmetry and extent of thoracic movement during inspiration.

- Is usually symmetrical and is at least 2.5 centimeters between full expiration and full inspiration.

- Can be symmetrically diminished in ankylosing spondylitis .

- Can be unilaterally diminished in chronic fibrotic lung disease , extensive lobar pneumonia, large pleural effusions, bronchial obstruction and other disease states.

Percussion:

Percussion is the act of tapping on a surface, thereby setting the underlying structures in motion, creating a sound and palpable vibration. Percussion is used to determine whether underlying structures are fluid-filled, gas-filled, or solid. Percussion:

- Penetrates 5 - 6 centimeters into the chest cavity.

- May be impeded by a very thick chest wall.

- Produces a low-pitched, resonant note of high amplitude over normal gas-filled lungs.

- Produces a dull, short note whenever fluid or solid tissue replaces air filled lung (for example lobar pneumonia or mass) or when there is fluid in the pleural space (for example serous fluid, blood or pus).

- Produces a hyperresonant note over hyperinflated lungs (e.g. COPD ).

- Produces a tympanitic note over no lung tissue (e.g. pneumothorax ).

Diaphragmatic excursion:

- Can be evaluated via percussion.

- Is 4-6 centimeters between full inspiration and full expiration.

- May be abnormal with hyperinflation , atelectasis , the presence of a pleural effusion , diaphragmatic paralysis, or at times with intra-abdominal pathology.

Registered Nurse RN

Registered Nurse, Free Care Plans, Free NCLEX Review, Nurse Salary, and much more. Join the nursing revolution.

Body Movement Terms – Anatomy Body Planes of Motions

In this anatomy lesson, I’m going to cover all of the major body movement terms for anatomy (also called the planes of motion ) that can occur at the synovial joints. You’ll come across these in your anatomy or kinesiology courses, and if you pursue a career in healthcare, you’ll use these terms during documentation or patient assessments.

After you review these notes and the corresponding video, you can take a comprehensive quiz on anatomy body movement terms .

Categories of Body Movement Terms in Anatomy

There are four major categories of body movements that can occur at the synovial joints:

- Gliding movement

- Angular movements

- Rotational movements

- Special movements

Gliding Movement in Anatomy

What is gliding ? Gliding occurs when the surfaces of bones slide past one another in a linear direction, but without significant rotary or angular movement.

An example of this movement is moving your hand back and forth (left to right) in a waving motion, which causes gliding to occur at the joints of the carpals ( wrist bones ). When you move your hand back and forth in a waving motion, it can help you remember that gliding joint movements primarily take place in the carpals of the wrist and the tarsals of the ankle.

However, gliding can also occur in the other plane joints (also called planar joints) of the body. Just as airplanes glide through the air, the plane joints of the body allow a gliding motion.

Other plane joints that allow gliding include the sacroiliac joint of the pelvis , the acromioclavicular joint of the shoulder, the femoropatellar joint , tibiofibular joint , sternocostal joints for ribs 2-7, vertebrocostal joints , and the intervertebral joints of the spine (at the articular processes).

Angular Movements in Anatomy

The next category of body movement terms consists of the angular movements, which consist of the following movements:

- Flexion and Extension

- Abduction and Adduction

- Circumduction

Flexion and Extension in Anatomy

Because flexion and extension are angular movements, I find it really helpful to visualize an angle during the actual movement. Flexion decreases the angle between two structures or joints as they bend or move closer together, whereas extension increases the angle between them as they straighten and move apart.

Elbow Flexion and Extension

Elbow flexion (also called forearm flexion ) occurs when the angle between the forearm and arm decreases, allowing the ulna of the forearm to move closer to the humerus bone of the arm.

In contrast, elbow extension ( forearm extension ) occurs when the forearm moves away from the arm, increasing the angle between those bones.

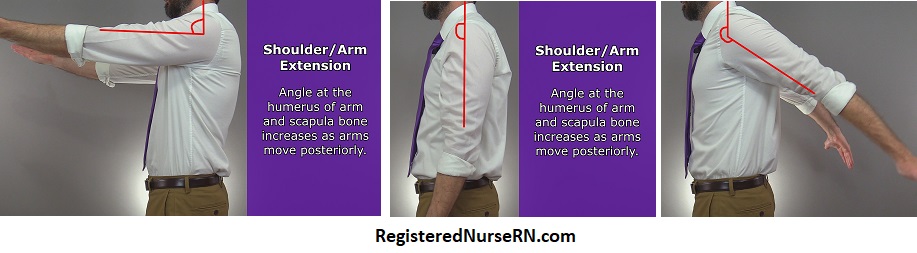

Shoulder Flexion and Extension

Shoulder flexion , also called arm flexion , occurs when the angle at the humerus of the arm and the scapula decreases as the arms move anteriorly. In contrast, shoulder extension (or arm extension ) occurs when the angle at the humerus of the arm and the scapula increases, causing the arm to move posteriorly. The joint here allows movement past the anatomical position. Some anatomists call arm movement beyond the anatomical position extension , whereas some call it hyperextension .

Wrist Flexion and Extension

Wrist flexion (also called hand flexion ) occurs when the angle between the palm of the hand and the anterior surface of the forearm decreases, while wrist extension (or hand extension ) is moving the palm of the hand away from the anterior surface of the forearm, hence the angle increases. This is another joint that can continue to move past the anatomical position in a posterior direction, which some anatomists call hyperextension.

Finger Flexion and Extension

Finger flexion occurs when the angle between the fingers and the palm decreases, as the fingers move toward the palm. When the angle between the fingers and the palm increases, finger extension occurs.

Flexion and extension also occur with the interphalangeal joints of the fingers (digits 2-5), including the distal interphalangeal joint (dip) and proximal interphalangeal joint (pip).

Thumb Flexion and Extension

The thumb (pollex) can confuse people because thumb flexion and extension occur in the frontal plane , which is a different direction than flexion of the fingers, which occurred in the sagittal plane. Thumb flexion moves the thumb toward the pinky finger, whereas extension moves the thumb away from the pinky finger. Think of your palm as a windshield and your thumb as the windshield wiper for this movement.

Flexion and extension can also occur at the interphalangeal joint of the thumb.

Hip Flexion and Extension

Hip flexion (or thigh flexion ) occurs when the angle between the femur of the thigh and hipbone decreases as the thigh moves anteriorly (forward). Hip extension ( thigh extension ) occurs when the angle between the femur and the hip bone increases, as the hip joint straightens. This joint also allows posterior movement past the anatomical position, which some anatomists call hyperextension.

Knee Flexion and Extension

Knee flexion ( leg flexion ) occurs when the tibia bone moves toward the femur, causing the angle to decrease between those two structures. Knee extension (or leg extension ) occurs as the angle between the leg bones increases, causing the leg to straighten.

Toe Flexion and Extension

Like the fingers, toe flexion and extension can also occur. Toe flexion involves bending the toes toward the sole of the foot, decreasing the angle between these two structures, while toe extension involves increasing the angle and straightening the toes.

Note : instead of using flexion and extension for the movement of the foot at the ankle joint, anatomists prefer to use the terms plantarflexion and dorsiflexion .

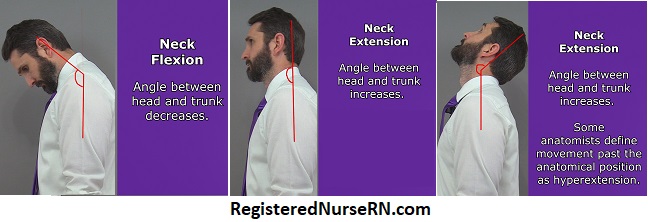

Neck Flexion and Extension

Neck flexion occurs as the angle between the head and the trunk of the body decreases as those two structures move closer together, whereas neck extension occurs as the head moves away from the trunk of the body, thus increasing the angle. The neck is another structure that can continue posteriorly, beyond the anatomical position, which some anatomists call hyperextension of the neck .

Vertebral Column Flexion and Extension

Vertebral column flexion at the trunk, (spine flexion) occurs when the angle between the trunk and the hip joint decreases. Vertebral column (spine) extension at the trunk occurs as the spine straightens and the angle between the hip joint and spine increases.

By the way, you might have noticed that most of these movements so far are occurring within (or parallel to) the sagittal plane. However, just like the thumb, flexion can also occur in the frontal (coronal) plane for the vertebral column. For example, if you bend the spine to the left or right, that’s called lateral flexion , and movement back toward the anatomical position is called lateral extension .

Note: you might want to watch our other lecture if you are unfamiliar with the different body planes .

Hyperextension

Finally, when extension of a structure moves beyond a certain point, anatomists call it hyperextension. However, anatomists differ on what constitutes hyperextension when it comes to body movement terms.

For example, some anatomists say that when the arm , neck , wrist , or thigh moves past the anatomical position in a posterior motion, it becomes hyperextension . Other anatomists only consider these movements hyperextension if the movement exceeds the normal range of motion permitted by the joint. For test-taking purposes, follow your anatomy teacher’s definition!

Abduction and Adduction in Anatomy

Unlike flexion and extension movements, which mostly take place within the sagittal plane , you’ll notice that abduction and adduction motions mostly take place within the frontal, or coronal, plane. However, the thumb is a notable exception to this rule, as it moves within the sagittal plane during abduction and adduction when in the anatomical position .

What is Abduction?

Abduction (think: ABDUCT ion) is the movement of a structure away from its midline reference point. Let the name help you out. What does “abduct” mean? When you hear on the news that a man was abducted, you know it means that someone took him away . That’s exactly what’s going on with this movement. The structure is being moved away from its midline reference point.

What is Adduction?

Adduction (think: ADD uction) occurs as the structure is ADDED back toward its midline reference point.

Let’s take a look at examples of abduction and adduction on the body.

Arm Abduction and Adduction

During arm abduction (also called shoulder abduction), the arms move away from the body’s midline. During arm adduction (or shoulder adduction), you ADD them right back toward the midline.

Finger Abduction and Adduction

Finger abduction occurs when the fingers move away from the midline reference of the hand, whereas finger adduction occurs when you add them back toward the hand’s midline reference.

When the middle finger (3rd digit), which serves as the midline reference of the hand, deviates to the away from the body, it’s called lateral abduction . When it deviates toward the body, it’s called medial abduction .

Thumb Abduction and Adduction

The thumb (pollex) is different from the fingers. Abduction of the thumb has it moving within the sagittal plane, in an anterior motion. Adduction of the thumb has it added back to the hand.

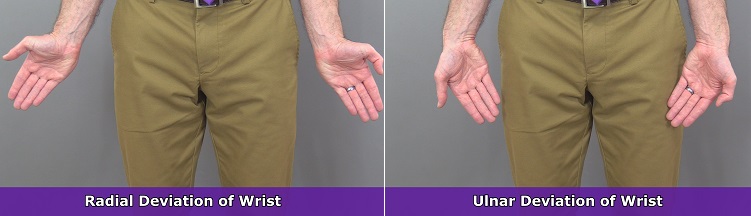

Wrist Abduction and Adduction (Ulnar Deviation & Radial Deviation)

When determining abduction and adduction of the wrist, I find that it helps to stand in the anatomical position. Abduction of the wrist has it moving away from the body’s midline, in the same direction as arm abduction. Adduction of the wrist has it going in the opposite direction, toward the body’s midline.

These movements are also referred to as radial deviation and ulnar deviation . Remember, the radius is on the thumb side, which where you check the radial pulse. So radial deviation is movement on the radial side, whereas ulnar deviation occurs on the opposite side.

Thigh Abduction and Adduction

During thigh abduction (also called hip abduction or leg abduction), the lower limb moves away from the body’s midline. During adduction of the thigh , you ADD the lower limb right back toward the body’s midline.

Toes Abduction and Adduction

When the toes move away from the midline of the foot, toe abduction occurs. Toe adduction adds them right back together.

Just like with the hand, devation of the 2nd toe away from the body’s midline is called lateral abduction , whereas movement toward the midline is called medial abduction .

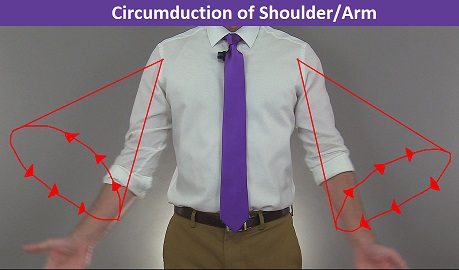

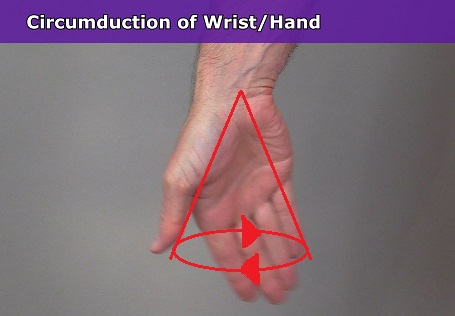

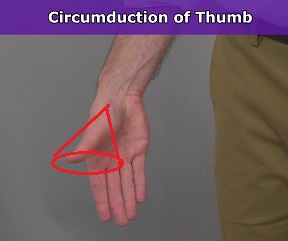

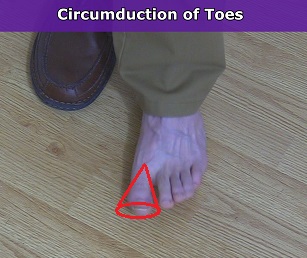

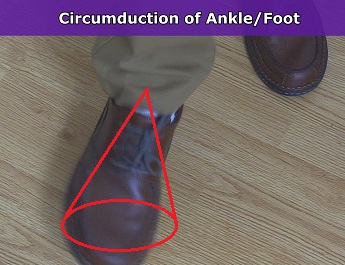

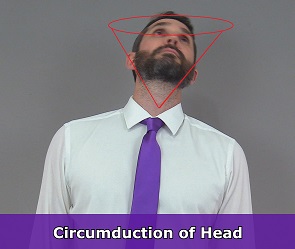

Circumduction in Anatomy

The final body movement term in this category is circumduction , which is an angular movement that blends the motions of flexion , abduction , extension, and adduction to create a circular or conical motion of the attached structure.

The word circ umduction starts with the same letters as the word “ circ le,” so that will tip you off that this movement creates a circular, or conical, movement in the structure extending beyond the joint.

Circumduction Movement Demonstrated

Because circumduction is a combined movement, I find it helpful to think about the individual movements in slow motion. Looking at the shoulder joint, I’ll begin with arm flexion and then arm abduction. Next is arm extension , followed by arm adduction . When you combine those movements into one smooth motion, you can see how it forms a cone or circle.

The mnemonic “FABEA” might help you remember the order:

You could also reverse that order, but the movements have to alternate in a similar succession to create the circular motion that characterizes the circumduction movement.

Joints Capable of Circumduction

Where can circumduction occur on the body? Because it requires the motions of flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction, the joint will generally have to be capable of all four of those sequential movements. Below are examples of joints/structures that can perform the circumduction movement.

Circumduction of the Hip Joint (Thigh)

Circumduction of the Shoulder Joint (Arm)

Circumduction of the Wrist Joint (Hand)

Circumduction of the Thumb (Pollex)

Circumduction of the Fingers

Circumduction of the Toes

Circumduction of the Ankle Joint (Foot)

Circumduction of the Head

Rotation in Anatomy

The next category of the body planes of motion is rotation , which is a body movement term that describes a bone moving around a central axis.

Rotation Body Movement Term in Anatomy

When I think of the rotation body movement , I like to picture a screw turning to either the right or left, as that is similar to the rotation movement that can occur in the body.

Rotation can occur at the head/neck, vertebral column, and the ball-and-socket joints of the upper and lower limbs (shoulder joint and hip joint). Let’s take a look at these movements, starting with the head.

Head and Neck Rotation

The head can rotate laterally to either the left or right, thanks to the pivot joint between vertebrae C1 (atlas) and C2 (axis). Moving the head back toward the anatomical position is medial rotation of the head.

Trunk Rotation

The vertebral column can also rotate laterally to either the left or right. Returning the trunk back toward the anatomical position is medial rotation of the trunk.

Arm Rotation (Medial and Lateral)

The ball-and-socket joint of the shoulder allows the humerus of the arm to rotate laterally, or away from the body’s midline , which is also called external rotation. It can also rotate medially, or toward the body’s midline, which is also called internal rotation.

Thigh/Leg Rotation (Medial and Lateral)

The ball-and-socket joint of the hip allows rotation of the thigh’s femur . Like the humerus, it can rotate laterally, or away from the body’s midline, which is also called external rotation. It can also rotate medially, or toward the body’s midline, creating an internal rotation movement.

Tip for Medial vs Lateral Limb Rotation

Be sure to focus on the anterior surface of the femur or humerus when you do this movement, because that’s the focal point for determining medial vs lateral rotation.

Special Body Movement Terms in Anatomy

The final category of body movement terms include the “special movements.” These movements don’t fall neatly into the categories I’ve already listed, so they are placed in their own unique category. The special movements involve the following:

Supination and Pronation

- Dorsiflexion and Plantarflexion (also spelled plantar flexion)

Inversion and Eversion

Elevation and depression.

- Protraction and Retraction

- Protrusion, Retrusion, and Excursion

- Opposition and Reposition

Supination and pronation are special movements involving rotation of the forearm .

Supination of Forearm and Hand

During supination , the distal end of the radius bone rotates over the ulna bone in a lateral direction . Lateral rotation means it is rotating away from the body’s midline.

I like to watch the thumb during this movement, because it is on the same side as the radius (hence, the radial pulse is located below the thumb). When the thumb is rotating away from the body’s midline, supination is occurring.

Pronation of Forearm and Hand

In contrast, pronation is the opposite movement: the distal end of the radius rotates over the ulna medially, and the two bones cross. Medial rotation is toward the body’s midline. So when the thumbs point toward the middle of the body, you know that pronation has occurred.

Palm Orientation During Supination and Pronation

You can also look at the orientation of the palms. During supination, the palms will face anteriorly (forward), which is their natural orientation in the anatomical position. However, if you flex the elbow about 90 degrees, the palms would then be facing up (superiorly).

Pronation has the palms facing the opposite direction: posteriorly (toward the back) when in the anatomical position, or down (inferiorly) when the elbow flexes to around 90 degrees. This is another reason why I like to look at the thumbs during this movement. Thumbs will point away from the body’s midline during supination, and toward the body during pronation, regardless of how the elbow is flexed.

Supination vs Pronation Mnemonic

Here’s a simple mnemonic (memory trick) to help you remember pronation vs supination special movements:

At the grocery store, you pro nate to pick up your pro duce, and you sup inate to eat it for sup per.

Also, if you want to take your vitamins, you pro nate to p our, and you sup inate to take your sup plements.

Plantarflexion and Dorsiflexion

In this continued series on body movements of anatomy, I’m going to demonstrate dorsiflexion and plantarflexion (or plantar flexion), which are special movements involving the foot and ankle joint.

Dorsiflexion vs Plantarflexion

To help you understand this special movement, let’s break down the words.

Dorsal Side of the Foot (Dorsum)

Dorsal refers to the back (or upper) side of something. In my video on body cavities and membranes , I used the example of a dorsal fin of a dolphin to help you remember that dorsal refers to the backside of a surface. Your toenails are on the dorsal side of the foot, because they are on the back (or upper) side of it.

Plantar Side of Foot (Sole)

In contrast, plantar refers to the sole (or bottom) of the foot. If you’ve ever had a plantar wart, then you’ve had a wart on the sole of your foot (ouch!).

Flexion Meaning

Flexion refers to the movement that decreases the angle between two surfaces or joints, usually within the sagittal plane of the body. Now, let’s put all these words together, and you’ll be able to remember the difference between plantarflexion vs dorsiflexion .

Dorsiflexion Example

During dorsiflexion , the back (upper) side of the foot moves toward the shin, decreasing the angle between these two surfaces, leaving the toes pointing closer toward your head. When you try to walk on your heels only, you dorsiflex the foot.

Plantar Flexion (Plantarflexion) Example

During plantar flexion , the sole of the foot angles downward toward the calf, decreasing the angle between those two surfaces, leaving the toes pointing farther away from the body. When you perform calf raises in the gym or walk on your tip toes, you plantar flex the foot. If you need help remember the direction of this movement, just remember this phrase: “Plantarflexion helps you stand on your toes and walk in any direction!”

Next, I’m going to demonstrate inversion and eversion , which are special movements that cause the foot to move relative to the body’s midline.

Inversion of the Foot

During inversion , the bottom of the foot (sole) turns so that it faces toward the body’s midline, in a medial orientation. Inversion starts with the word “in,” so that’s the dead giveaway that the sole is pointing in wardly (medially).

Eversion of the Foot

During eversion , the opposition motion occurs: the bottom of the foot turns so that it faces away from the body’s midline (laterally). The word “evert” literally means to “turn outward,” which is exactly what happens during eversion!

Now lets’s examine elevation and depression, which are special body movement terms that describe motion in a superior (up) or inferior (down) direction.

Elevation in Anatomy

Elevation refers to movement of a body part in a superior direction, or moving upward. When you walk into a hotel lobby, you have to get on the elevator to go up, right? We’d also say that a mountain has a peak “elevation” of 20,000 feet. Therefore, the term is pretty self-explanatory: elevation has a structure moving up, or superiorly.

Depression in Anatomy

Depression refers to movement of a body part in an inferior direction, or moving downward. When you are depressed, you feel down in the dumps, right? Therefore, depression is easy to remember as movement in an inferior, or downward direction.

Elevation and Depression in Anatomy

In anatomy, elevation and depression most commonly describe movements of the mandible (lower jaw) or scapulae (shoulder blades) within the frontal plane . When you move your lower jaw (mandible) in a downward direction, depression occurs. When you move your mandible upward, elevation occurs.

Similarly, when you move your scapulae up, elevation of the shoulder girdle occurs. When you move them back down, depression of the shoulder girdle occurs.

Protraction and Retraction in Anatomy

Now let’s discuss protraction and retraction , which are special body movements in anatomy that most commonly involve the scapulae (shoulder blades).

Protraction Movement

Protraction moves the scapula forward (anteriorly) and toward the side of the body (laterally) in an anterolateral direction.

Retraction Movement

Retraction is the opposite movement. It causes the shoulder blades to move back (posteriorly) and toward the body’s midline (medially). This movement is known as a posteromedial movement.

Protraction and Retraction Mnemonic

Here’s a simple way to remember protraction and retraction body movements in anatomy:

- You Retract when you Reach Back !

- You P unch to P rotract! In fact, the serratus anterior muscles assist with protraction of the scapulae, and they even call this muscle the boxer’s muscle for that very reason.

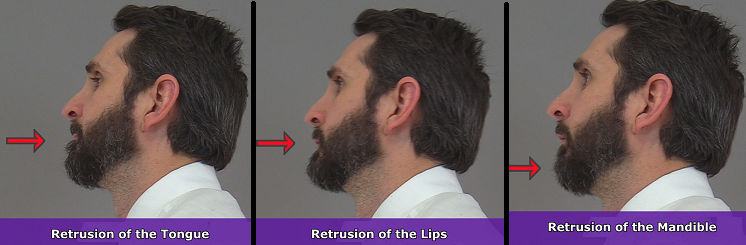

Protrusion, Retrusion, and Excursion in Anatomy

In this anatomy lesson, I’m going to demonstrate protrusion, retrusion, and excursion , which are special body movement terms in anatomy that refer to forward (anterior), backward (posterior), or side to side movements.

Protrusion in Anatomy

Protrusion refers to the movement of a structure in an anterior (forward) direction. In fact, the word protrude means “projecting something forward.”

I call protrusion the kissing movement because it occurs when you pucker your lips like you’re going to give someone a kiss or stick out your tongue. Moving the mandible (lower jaw) forward is also an example of protrusion.

Retrusion in Anatomy

Retrusion is the opposite of protrusion. It refers to the movement of a structure in a posterior, or backward, direction. Putting your tongue back in your mouth, moving the lips back, or moving the mandible back are all examples of retrusion in anatomy.

Excursion in Anatomy

Finally, we have excursion , which refers to the side-to-side movement of the lower jaw (mandible). If you’ve ever heard of a character named Ernest P. Worrell, then you’ve definitely seen the excursion movement. He’s the character in those movies such as Ernest Goes to Camp, Ernest Goes to Jail, etc. When Ernest saw something nasty, he’d move his jaw back and forth and say, “Ewwww.”

Excursion can occur in either direction, and anatomists use directional terms to specify the type of excursion. When the mandible moves to either the left or right, it’s moving away from the body’s midline, so it’s called lateral excursion . When the mandible moves closer to the midline of the body, it’s called medial excursion .

Protrusion and Retrusion vs Protraction and Retraction

What about protraction and retraction ? Some anatomy textbooks will refer to the forward movement of the mandible, lips, or tongue as protraction (instead of protrusion), and the backward (posterior) movement will be called retraction (instead of retrusion). The terms are sometimes used interchangeably, so use whatever method your anatomy professor suggests (they give you the grade, not me!).

However, some anatomists today use protraction and retraction to refer almost exclusively to the scapulae, as it is a combined movement (protraction is anterolateral, and retraction is posteromedial). In contrast, protrusion and retrusion are more of an anterior/posterior movement. Then again, some anatomists prefer not to use protraction and retraction at all, even when describing shoulder blade movement.

Opposition and Reposition of the Thumb: Anatomy

Finally, I’ll demonstrate opposition and reposition , which are special movements involving the thumb.

The thumb, also known as the pollex or digit one, articulates (forms a joint) with the trapezium bone of the wrist (carpus) via a saddle joint, which is a type of synovial joint featuring interlocking convex and concave surfaces. They call it a saddle joint because, well, it kinda looks like a saddle (yee-haw, cowboy!).

Thanks to this saddle joint, the thumb can perform circumduction, flexion and extension, abduction and adduction, as well as special movements called opposition and reposition .

Opposition of the Thumb

Opposition of the thumb occurs when the tip of the thumb comes to meet (and oppose) the tip of another finger from the same hand. A super easy way to remember this is that you’ve probably heard someone say that humans have opposable thumbs. Oppos ition is the special movement of our oppos able thumbs.

In fact, think about this: when the opposition movement occurs, what happens? In the picture above, did you notice how the thumb and finger created a shape similar to the letter ‘O’? The ‘O’ stands for opposition! Now you can easily remember this motion of our opposable thumbs!

Reposition of the Thumb

Reposition is the opposite action of opposition. During reposition, the thumb and finger return to their original position.

Free Quiz and More Anatomy Videos

Take a free comprehensive quiz on body movement terms to test your knowledge, or review our anatomy body movement terms video . In addition, you might want to watch our anatomy and physiology lectures on YouTube, or check our anatomy and physiology notes .

Please Share:

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

Disclosure and Privacy Policy

Important links, follow us on social media.

- Facebook Nursing

- Instagram Nursing

- TikTok Nurse

- Twitter Nursing

- YouTube Nursing

Copyright Notice

1. Download the Taber's Online app by Unbound Medicine

2. Log in using your existing username and password to start your free, 30-day trial of the app

3. After 30 days, you will automatically be upgraded to a 1-year subscription at a discounted rate of $29.95

Type your tag names separated by a space and hit enter

There's more to see -- the rest of this topic is available only to subscribers.

2. Select Try/Buy and follow instructions to begin your free 30-day trial

We're glad you have enjoyed Taber's Online! As a thank-you for using our site, here's a discounted rate for renewal or upgrade.

Mobile + Web Renewal

1 Year Subscription

Consult Taber’s anywhere you go with web access + our easy-to-use mobile app.

Nursing Central

Nursing Central combines Taber’s with a medical dictionary, disease manual, lab guide, and useful tools.

Not now - I'd like more time to decide

Want to regain access to Taber's Online?

Renew my subscription

Log in to Taber's Online

Forgot your password, forgot your username, contact support.

- unboundmedicine.com/support

- [email protected]

- 610-627-9090 (Monday - Friday, 9 AM - 5 PM EST.)

Type your tag names separated by a space and hit enter

There's more to see -- the rest of this topic is available only to subscribers.

1. Download the Nursing Central app by Unbound Medicine

2. Select Try/Buy and follow instructions to begin your free 30-day trial

Want to regain access to Nursing Central?

Renew my subscription

Not now - I'd like more time to decide

Log in to Nursing Central

Forgot your password, forgot your username, contact support.

- unboundmedicine.com/support

- [email protected]

- 610-627-9090 (Monday - Friday, 9 AM - 5 PM EST.)

Medical Dictionary

Search medical terms and abbreviations with the most up-to-date and comprehensive medical dictionary from the reference experts at Merriam-Webster. Master today's medical vocabulary. Become an informed health-care consumer!

Browse the Medical Dictionary

Featured game.

Find the Best Synonym

Test your vocabulary with our 10-question quiz!

Deniz Burnham & 'Astronaut'

Peyton Manning & 'Omaha'

Issa Rae & 'Insecure'

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Games & Quizzes

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Multidiscip Respir Med

- v.17; 2022 Jan 12

Diaphragmatic excursion by ultrasound: reference values for the normal population; a cross-sectional study in Egypt

Ahmed e. kabil.

1 Chest Diseases Department, Faculty of Medicine, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

2 Chest Diseases Department, Faculty of Medicine for Girls, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt

3 College of Medical Rehabilitation Sciences, Taibah University, Medina, Saudi Arabia

Mahmoud Elsaeed

Houssam eldin hassanin, ibrahim h. yousef, heba h. eltrawy, ahmed m. ewis, ahmed aboseif, abdallah m. albalsha, sawsan elsawy, abdul rahman h. ali.

4 Mahatma Gandhi University, Meghalaya, India

Publisher's note: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Measurement of diaphragmatic motion by ultrasound is being utilized in different aspects of clinical practice. Defining reference values of the diaphragmatic excursion is important to identify those with diaphragmatic motion abnormalities. This study aimed to define the normal range of diaphragmatic motion (reference values) by Mmode ultrasound for the normal population.

Healthy volunteers were included in this study. Those with comorbidities, skeletal deformity, acute or chronic respiratory illness were excluded. Diaphragmatic ultrasound in the supine position was performed using a lowfrequency probe. The B-mode was applied for diaphragmatic identification, and the M-mode was employed for the recording of the amplitude of diaphragm contraction during quiet breathing, deep breathing and sniffing.

The study included 757 healthy subjects [478 men (63.14%) and 279 women (36.86%)] with normal spirometry and negative history of previous or current respiratory illness. Their mean age and BMI were 45.17 ±14.84 years and 29.36±19.68 (kg/m 2 ). The mean right hemidiaphragmatic excursion was 2.32±0.54, 5.54±1.26 and 2.90±0.63 for quiet breathing, deep breathing and sniffing, respectively, while the left hemidiaphragmatic excursion was 2.35±0.54, 5.30±1.21 and 2.97±0.56 cm for quiet breathing, deep breathing and sniffing, respectively. There was a statistically significant difference between right and left diaphragmatic excursion among all studied subjects. The ratio of right to left diaphragmatic excursion during quiet breathing was (1.009±0.19); maximum 181% and minimum 28%. Only 19 cases showed a right to left ratio of less than 50% (5 men and 14 women). The diaphragmatic excursion was higher in males than females. There was a significant difference in diaphragmatic excursion among age groups. Age, sex and BMI significantly affected the diaphragmatic motion.

Conclusions

Diaphragmatic excursion values presented in this study can be used as reference values to detect diaphragmatic dysfunction in clinical practice. Diaphragmatic motion is affected by several factors including age, sex and body mass index.

Introduction

The diaphragm is the main muscle of respiration [ 1 ]. Diaphragmatic excursion is 1-2 cm during tidal breathing and 7-11 cm during deep inspiration [ 2 ]. The assessment of diaphragmatic function is important for diagnosis and follow up of various physiologic and pathologic conditions [ 1-4 ]. Several methods exist for the evaluation of diaphragmatic function. These methods include fluoroscopy [ 3 ], computed tomography [ 4 ], magnetic resonance imaging [ 2 ], and ultrasonography [ 5 ]. Thoracic ultrasound has been reported to be a useful tool for the examination of diaphragmatic function [ 6 ]. It is a bedside non-invasive tool that provides various techniques for evaluation of diaphragmatic function including measurement of diaphragmatic excursion and thickness as well as changes during different phases of inspiration [ 7 ]. Ultrasonography has been proved to be superior to fluoroscopy and can provide accurate measurement of diaphragmatic excursion [ 3 ]. Previous studies highlighted the lack of reference values for diaphragmatic excursion in the normal population which complicates diagnosing abnormal diaphragmatic motion in certain diseases. No data is available about diaphragmatic motion in the normal Egyptian population and no reference data are available to compare with. This study aimed to explore the normal diaphragmatic excursion in the Egyptian population by M-mode ultrasonography.

This is a cross-sectional study that initially included 780 participants. Twenty-three subjects were excluded due to poor images or failed visualization of one hemidiaphragm, rendering the finally included number 757 individuals (478 males and 279 females), all had normal lung functions with no history of chest disease. Smokers, those with acute respiratory illness, chronic respiratory disease, associated comorbidities, physical disability, abnormal pulmonary function tests or history of anesthesia within the past six months were excluded from the study.

Pulmonary functions were done using spirometry (Spirosift 5000; Fukuda Denshi, Beijing, China). The operator encouraged all subjects verbally to exhale as fast and as deep as possible. Each subject performed at least three technically accepted measurements, and the best of them was selected for statistical analysis. All measurements were performed according to ERS/ATS standards [ 7 ].

Diaphragmatic ultrasound

All sonographic examinations were done by the research team. Inter-operator and intra-operator variability were excellent (data not shown). Examinations were performed at quiet temperature (22-25C°). All subjects were asked to rest for 30 min before sonography. Ultrasonography was done using an ultrasound device (SSI6000; Sonoscape, Nanshan, China), while subjects located in the supine position. Examinations were performed using 3.5 MHz curvilinear probe. Each hemidiaphragm was first visualized by Bmode, then M-mode was used to evaluate diaphragmatic excursion in tidal breathing, deep breathing and sniff. The right hemidiaphragm was measured by positioning the probe between the midclavicular and midaxillary lines below the right costal margin (subcostal approach), using the liver as an acoustic window. The probe was directed medially, cephalic and dorsally. When the hemidiaphragm was well visualized, the M-mode was applied to measure the excursion [ 8 ]. The left hemidiaphragm was visualized using the spleen as an acoustic window. The probe was positioned between the left midclavicular and midaxillary lines below the left costal margin. The probe was directed in the same way as the right side [ 8 ]. Targeting to improve visualization of the left hemidiaphragm, and overcome the small acoustic window of spleen, the probe was sometimes displaced caudally in the abdomen to obtain a better angle for visualization. The diaphragm was seen as a single echogenic line ( Figure 1 ), moving towards the probe during inspiration and away from the probe during expiration [ 5 ]. Diaphragmatic excursion was defined as the difference between the highest point and steep point (amplitude). The diaphragmatic excursion was recorded in different respiratory phases; tidal breathing (normal quiet inspiration), deep inspiration (holding up breathing after maximal inspiration), and sniffing (quick nasal inspiration with a closed mouth) ( Figure 2 ). The direction of movement was also observed (normal or paradoxical), as absent or paradoxical motion may indicate diaphragm paralysis.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed by SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) software version 19 (IBM corp., Armonk, NY, USA) after data cleaning and check. Numerical data were presented as mean ±SD, while categorical data were presented as number (percentage). Independent sample t-test and ANOVA were used for comparisons, Pearson correlation coefficient for testing the relationship between diaphragmatic excursion and demographic parameters, and linear regression analysis for the detection of factors affecting diaphragmatic motion. The significance level was set at a p≤0.05.

Totally, 757 healthy subjects with normal spirometry were included in this study [478 men (63.14%) and 279 women (36.86%)]. The mean age of the study population was 45.17±14.84 years. Men were significantly older, had significantly higher FVC% and VT%, while women had significantly higher body mass index (BMI) and better FEF25-75% ( Table 1 ). There was a statistically significant difference between right and left diaphragmatic excursion among all studied subjects ( Table 2 ). The ratio of right to left diaphragmatic excursion during quiet breathing was (1.009±0.19); maximum 181% and minimum 28%. Only 19 cases showed a right to left ratio less than 50% (5 men and 14 women). Right diaphrag- matic motion was significantly higher in men than in women ( Table 3 ). There were significant differences in diaphragmatic excursion among age groups ( Table 4 ). However, there were no statistically significant differences among BMI categories ( Table 5 ). A statistically significant positive correlation was found between age and right diaphragmatic excursion during both deep breathing and sniffing, and between age and left hemidiaphragmatic excursion during deep breathing (r=0.045, p˂0.001, r=0.117, p=0.001, r=0.190, p˂0.001, respectively). A statistically significant negative correlation was observed between age and left hemidiaphragmatic excursion during quiet breathing (r=-0.098, p=0.007). On the other hand, a statistically significant negative correlation was detected between BMI and right hemidiaphragmatic excursion during deep breathing and sniffing, and between BMI and left hemidiaphragmatic excursion during deep breathing (r = 0.182, p˂0.001; r = -0.094, p=0.009; r = -0.142, p˂0.001, respectively). A positive correlation between BMI and left hemidiaphragmatic excursion was found during quiet breathing (r = 0.148, p˂0.001) ( Table 6 ). Regression analysis revealed that sex, age, BMI and pulmonary functions affect diaphragmatic motion (good predictors). Age, sex and BMI index significantly affect diaphragmatic motion by variable extents during different types of breathing.

Right diaphragm visualization by B-mode ultrasound. The diaphragm is seen as a thick white line moving with respiration. The liver is used as an echogenic window.

Visualization and measurement of right diaphragmatic excursion by M-mode ultrasound. The diaphragm is seen as a white line moving with respiration. The diaphragmatic excursion is measured as the amplitude of wave seen in M-mode during breathing.

Demographic data and pulmonary functions of the studied population.

# Comparison between men and women

* p<0.05.

Diaphragmatic excursion in the normal population.

Diaphragmatic excursion according to sex.

# Comparison between men and women; *p<0.05.

Diaphragm accounts for three fourths of lung ventilation [ 9 ]. Diaphragmatic imaging is important for the diagnosis of diaphragmatic dysfunction or paralysis [ 3 , 9 ]. Normal values of diaphragmatic excursion are important to evaluate abnormalities in different diseases [ 8 ]. Diaphragmatic dysfunction (weakness or paralysis) is usually underdiagnosed in clinical practice [ 10 ]. Normal values can be used to detect either hypokinesia or hyperkinesia [ 11 ]. In this study we found that the mean diaphragmatic excursion for right hemidiaphragm during quiet breathing was 2.32±0.54 cm, while that for the left one was 2.35±0.54 cm. The mean diaphragmatic excursion during deep breathing was 5.54±1.26 cm for the right side and 5.30±1.21 cm for the left, whereas the excursion during sniffing was 2.90±0.63 cm for the right side and 2.97±0.56 cm for the contralateral hemidiaphragm. These results are in line with the results of previous reports [ 5-7 ]. Normal diaphragmatic excursion in tidal breathing in previous studies was reported to be from 1-2.5 cm [ 8 ]. These values can be affected by age, sex, body composition [ 12 , 13 ], scanning position, and phase of inspiration [ 14 ]. Right diaphragmatic excursion was shown to be significantly better in men than in women ( Table 3 ). The same results were reported by Kantarci et al . who in their study reported a significant difference in diaphragmatic motion between male and female subjects [ 13 ]. In their study, sex was the most significant factor affecting diaphragmatic function. In our study, there was a significant difference in diaphragmatic excursion among age groups ( Table 4 ). Similar results were reported in previous studies [ 6 , 8 ]. Boussuges et al. [ 8 ] reported a higher diaphragmatic excursion in men than women in all types of breathing. This can be attributed to differences in height, weight, age [ 6 , 8 ], diaphragmatic mass, diaphragmatic fiber type property, metabolic activity, contractile properties and environmental factors [ 9 ].

In the current study, a statistically significant positive correlation was observed between age and diaphragmatic excursion during both deep breathing and sniffing in the right side, and during deep breathing only in the left one. Besides, a statistically significant negative correlation was revealed between age and left hemidiaphragmatic excursion during quiet breathing ( Table 4 ). Kantarci et al . [ 13 ] found that diaphragmatic function is significantly lower in the individuals below 30 years when compared to those aged more than 30 years.

We did not find any significant statistical differences among BMI categories ( Table 5 ). However, there was a significant positive correlation between BMI and left hemidiaphragmatic excursion during quiet breathing ( Table 6 ). Moreover, regression analysis showed that age, sex and BMI are the main factors that significantly affect diaphragmatic excursion. Kantarci et al . [ 13 ] reported a significant difference in diaphragmatic motion according to BMI categories and explained this by the difference in fat and muscle composition. In the same context, Scarlata et al . [ 12 ] reported a significant correlation between diaphragmatic motion and gender, age, weight and height. This difference is clinically important for the identification of those with a risk of low diaphragmatic function to include them in rehabilitation programs. This discrepancy between studies may be due to different demographic characters and distribution of population in different body mass index categories. Increased diaphragmatic motion with increased BMI may be attributed to differences in height or the increased diaphragm weight with increased body weight [ 10 ]. This can be confirmed through the assessment of diaphragmatic thickness by ultrasonography.

Diaphragmatic excursion according to age groups.

Diaphragmatic excursion according to BMI.

Correlation with body mass index and age and diaphragmatic excursion.

BMI, body mass index; **correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

The strengths of this study include the large number of studied populations, different age groups and body composition. This study reflects the normal distribution of diaphragmatic excursion in the normal population in Egypt. Knowing normal references for diaphragmatic ultrasound measurements can be of clinical value in identifying and diagnosing diaphragmatic paralysis, as well as exploring the cause and predicting the prognosis of diaphragm paralysis [ 15 ]. Diaphragmatic ultrasound normal values can be also used to predict the response to treatment as in rehabilitation programs, in addition to setting cut-off values to predict successful weaning parameters from mechanical ventilation. Likewise, it can be used to evaluate diaphragmatic function before and after surgeries. Furthermore, these values can also predict diaphragmatic dysfunction and deconditioning [ 15 ]. They can be applied as a predictor of mechanical ventilation-induced diaphragm dysfunction, too [ 16 ]. The unequal distribution of age groups, the disparity of BMI among different age groups, together with the inability to perform a simultaneous assessment of pulmonary functions and diaphragmatic motion by ultrasound due to technical difficulties are the main limitations of this study. The study included only Egyptian volunteers, which may be considered another limitation, so large worldwide studies are recommended to reach worldwide normal values that can be applied to all countries. Also, further studies are needed for assessments of diaphragmatic functions in patients with chronic respiratory diseases.

Diaphragmatic excursion values presented in this study can be used as reference values to detect diaphragmatic dysfunction in clinical practice. There is a significant statistical difference between right and left hemidiaphragmatic movement during all types of breathing (quiet, deep and sniffing). Age, sex and BMI significantly affect diaphragmatic motion with variable extents during different types of breathing. The assessment of diaphragmatic motion by ultrasound could be a useful indicator for the diagnosis and follow up of respiratory diseases, and could be added to outcomes in clinical trials. Further studies to assess other factors that may affect the diaphragmatic motion including metabolic factors and other anthropometric parameters are required.

- Daily Crossword

- Word Puzzle

- Word Finder

Word of the Day

- Synonym of the Day

- Word of the Year

- Language stories

- All featured

- Gender and sexuality

- All pop culture

- Grammar Coach ™

- Writing hub

- Grammar essentials

- Commonly confused

- All writing tips

- Pop culture

- Writing tips

Advertisement

[ ik- skur -zh uh n , -sh uh n ]

a pleasure excursion; a scientific excursion.

weekend excursions to mountain resorts.

an excursion of tourists.

excursions into futile philosophizing.

- Physics. the displacement of a body or a point from a mean position or neutral value, as in an oscillation.

- an accidental increase in the power level of a reactor, usually forcing its emergency shutdown.

- the range of stroke of any moving part.

- the stroke itself.

- Obsolete. a sally or raid.

verb (used without object)

- to go on or take an excursion.

an excursion fare; an excursion bus.

/ -ʒən; ɪkˈskɜːʃən /

- a short outward and return journey, esp for relaxation, sightseeing, etc; outing

- a group of people going on such a journey

an excursion ticket

an excursion into politics

- (formerly) a raid or attack

- a movement from an equilibrium position, as in an oscillation

- the magnitude of this displacement

- the normal movement of a movable bodily organ or part from its resting position, such as the lateral movement of the lower jaw

- machinery the locus of a point on a moving part, esp the deflection of a whirling shaft

Discover More

Other words from.

- ex·cursion·al ex·cursion·ary adjective

- preex·cursion noun

Word History and Origins

Origin of excursion 1

Example Sentences

It’s important that your significant other or family is supportive, since your new obsession will likely become all-consuming, and most of your outdoor excursions will now revolve around searching for animal poop in the woods.

Insulated, waterproof footwear like the Paninaro Omni-Heat Tall Boot will go a long way in making your snow bike or snowshoe excursion a treat rather than a trial.

More time outdoors has been great for dialing in our kit for weekend excursions.

The thought of being able to knock out a three-day excursion with just a single carry-on is tantalizing.

I’ve spent the past two months testing the pack on a handful of short camp-outs and a seven-day family surf excursion, and the SEG42 delivered the organization I desperately needed.

It is disappointing and, frankly, frightening that Thompson walked away from his repugnant Sea World excursion scot-free.

Several events specifically cater to kids, making this a fun excursion for the whole family.

I learned a lot about myself on that excursion, and from the trip as a whole.

There was, instead, a nauseating excursion into base and sad fantasies.

While a two-day feeding frenzy makes for a fun excursion, the human body is only capable of so much consumption.

Out gets Uncle David, looking brown and healthy after his northern excursion.

The other day an excursion was arranged to Sondershausen, a town about three hours' ride from Weimar in the cars.

We got back to Weimar about eight in the evening, and this delicious excursion, like all others, had to end.

To my friends ever since I have not failed to recommend the passage of the Butterley tunnel as a desirable pleasure excursion.

From childhood I had longed to see something of the world, and this excursion to Paris was the first gratification of that wish.

Related Words

[ ak -s uh -lot-l ]

Start each day with the Word of the Day in your inbox!

By clicking "Sign Up", you are accepting Dictionary.com Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policies.

- Dictionaries home

- American English

- Collocations

- German-English

- Grammar home

- Practical English Usage

- Learn & Practise Grammar (Beta)

- Word Lists home

- My Word Lists

- Recent additions

- Resources home

- Text Checker

Definition of excursion noun from the Oxford Advanced American Dictionary

- trip an act of traveling from one place to another, and usually back again: a business trip a five-minute trip by taxi

- journey an act of traveling from one place to another, especially when they are far apart: a long and difficult journey across the mountains

- A trip usually involves you going to a place and back again; a journey is usually one-way. A trip is often shorter than a journey , although it does not have to be: a trip to New York a round-the-world trip. It is often short in time, even if it is long in distance. Journey is more often used when the traveling takes a long time and is difficult.

- tour a journey made for pleasure during which several different places are visited: a tour of California

- commute the regular trip that a person makes when they travel to work and back home again: a two-hour commute into downtown Washington

- expedition an organized journey with a particular purpose, especially to find out about a place that is not well known: the first expedition to the South Pole

- excursion a short trip made for pleasure, especially one that has been organized for a group of people: We went on an all-day excursion to the island.

- outing a short trip made for pleasure or education, usually with a group of people and lasting no more than a day: My project team organized an afternoon outing to celebrate.

- an overseas trip/journey/tour/expedition

- a bus/train trip/journey/tour

- to go on a(n) trip/journey/tour/expedition/excursion/outing

- to set out/off on a(n) trip/journey/tour/expedition/excursion

- to take a(n) trip/journey/expedition/excursion

Join our community to access the latest language learning and assessment tips from Oxford University Press!

- 2 excursion into something ( formal ) a short period of trying a new or different activity After a brief excursion into drama, he concentrated on his main interest, which was poetry.

Nearby words

- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Meaning of excursion – Learner’s Dictionary

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

(Definition of excursion from the Cambridge Learner's Dictionary © Cambridge University Press)

Translations of excursion

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

be chasing your tail

to be busy doing a lot of things but achieving very little

Binding, nailing, and gluing: talking about fastening things together

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- Learner’s Dictionary Noun

- Translations

- All translations

Add excursion to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

- Open access

- Published: 15 April 2024

Implementing spiritual care education into the teaching of palliative medicine: an outcome evaluation

- Yann-Nicolas Batzler 1 ,

- Nicola Stricker 2 , 3 ,

- Simone Bakus 4 ,

- Manuela Schallenburger 1 , 6 ,

- Jacqueline Schwartz 1 &

- Martin Neukirchen 1 , 5

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 411 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

162 Accesses

Metrics details

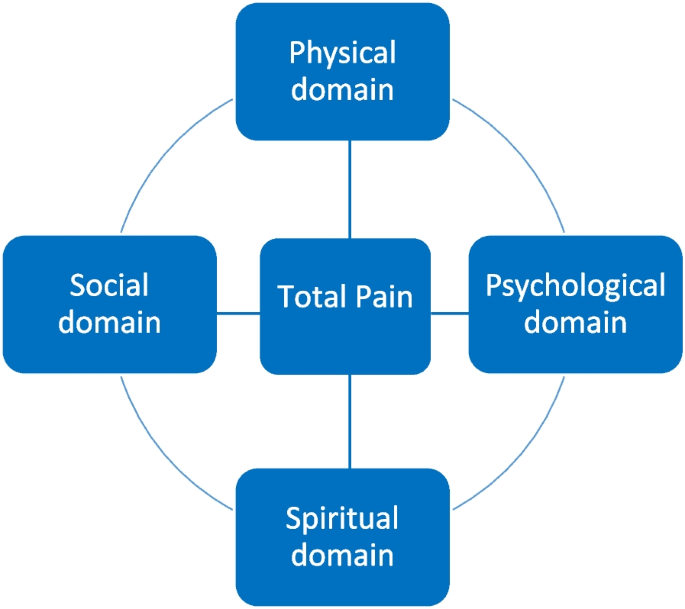

The concept of “total pain” plays an important role in palliative care; it means that pain is not solely experienced on a physical level, but also within a psychological, social and spiritual dimension. Understanding what spirituality entails, however, is a challenge for health care professionals, as is screening for the spiritual needs of patients.

This is a novel, interprofessional approach in teaching undergraduate medical students about spiritual care in the format of a seminar. The aim of this study is to assess if an increase in knowledge about spiritual care in the clinical context is achievable with this format.

In a mandatory seminar within the palliative care curriculum at our university, both a physician and a hospital chaplain teach strategies in symptom control from different perspectives (somatic domain – spiritual domain). For evaluation purposes of the content taught on the spiritual domain, we conducted a questionnaire consisting of two parts: specific outcome evaluation making use of the comparative self-assessment (CSA) gain and overall perception of the seminar using Likert scale.

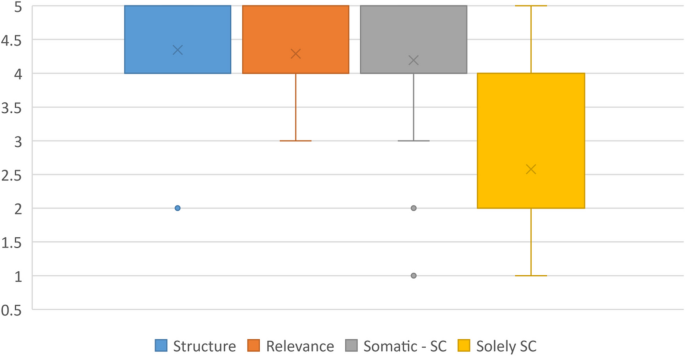

In total, 52 students participated. Regarding specific outcome evaluation, the greatest gain was achieved in the ability to define total pain (84.8%) and in realizing its relevance in clinical settings (77.4%). The lowest, but still fairly high improvement was achieved in the ability to identify patients who might benefit from spiritual counselling (60.9%). The learning benefits were all significant as confirmed by confidence intervals. Overall, students were satisfied with the structure of the seminar. The content was delivered clearly and comprehensibly reaching a mean score of 4.3 on Likert scale (4 = agree). The content was perceived as overall relevant to the later work in medicine (mean 4.3). Most students do not opt for a seminar solely revolving around spiritual care (mean 2.6).

Conclusions

We conclude that implementing spiritual care education following an interprofessional approach into existing medical curricula, e.g. palliative medicine, is feasible and well perceived among medical students. Students do not wish for a seminar which solely revolves around spiritual care but prefer a close link to clinical practice and strategies.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Education in palliative care was introduced in 2009 as a compulsory subject in German medical curricula. In the 1960s, Dame Cicely Saunders established palliative medicine and hospices as we know them today. Back then, Cicely Saunders propagated the concept of “total pain”, which means that pain or suffering in general is not solely experienced on a physical level, but also within a psychological, social and spiritual dimension (see. Fig. 1 ) [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. Understanding the importance of spirituality in everyday clinical practice and what it entails, however, is a challenge for health care professionals (HCP) in all medical disciplines across the world [ 5 , 6 ]. Palliative care is a relatively young medical discipline which oftentimes is not sufficiently taught in medical curricula [ 1 , 7 ] and, therefore, knowledge regarding the importance of spirituality, which at many faculties is integrated into palliative care education, is scarce [ 1 , 7 ]. As a result, HCP tend to neglect the spiritual needs of patients [ 7 , 8 ]. But, if there is no fundamental knowledge in regards of spirituality and spiritual care among physicians, how can they target total pain adequately?

The European Association of palliative care (EAPC) describes spirituality as following:

“Spirituality is the dynamic dimension of human life that relates to the way persons (individual and community) experience, express and/or seek meaning, purpose and transcendence, and the way they connect to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, to the significant and/or the sacred.” [ 1 , 9 ].

It must be clear to all HCP that spirituality is a unique and subjective phenomenon that differs substantially from patient to patient [ 2 , 10 ]. Furthermore, to fully address the spiritual needs of patients, self-reflection, thorough consideration of one’s own attitude towards death, and finding meaning in life, are essential [ 8 , 9 ]. Several studies have shown the impact which the addressing of spiritual needs in the context of total pain can have on ameliorating the symptoms of patients, leading to a better quality of life and care [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. Thus, once spiritual needs become imminent, it is necessary to engage in an interdisciplinary and multi-professional collaboration with specially trained professionals in the field of spiritual care [ 8 , 10 , 14 , 15 , 19 ]. Summing up, it is very important to raise awareness about the positive impact of spiritual care among HCPs [ 8 , 15 ]. To increase such knowledge and accrue such skills, the teaching of spiritual care in medical curricula is essential [ 20 ]. Throughout different regions in the world, in-person didactic teaching on spiritual care is the most commonly used technique [ 5 ]. Usually, the teaching is based on case studies and many include screening strategies assessing spiritual needs [ 5 ]. Often, education on spirituality and spiritual care is part of curricula in palliative care [ 5 , 21 ]. In German medical curricula, there is no compulsory subject solely revolving around spiritual care [ 22 ]. However, regarding the concept of total pain, implementing spiritual care into palliative care teaching, however, seems like a plausible proposition.

This study was conducted in order to assess the way medical students perceive the concept of implementing spiritual care into the teaching on symptom control in palliative care. Furthermore, we aimed to determine whether an actual increase of knowledge about spiritual care in the clinical context was achievable within this seminar.

Material and methods

This study is a single-centre prospective study conducted at University Hospital Duesseldorf, Germany. Ethical approval was obtained by the local ethics committee (reference number 2022–2274).

Curricular structure

At our facility, palliative care education is structured as followed: Five lectures (somatic symptoms, psychological symptoms, social symptoms and advance care planning, spiritual symptoms and end-of-life care and care for relatives, clinical ethics) and four seminars (symptom control, breaking bad news, clinical ethics I and II). Since 2022, the lecture on spiritual symptoms and end-of-life-care is held by both a physician and a hospital chaplain within the palliative care curriculum at Düsseldorf medical faculty. Beforehand, this lecture was solely held by a hospital chaplain. As internal evaluations implied, this concept was not well perceived by medical students as the relevance to daily clinical work was not apparent to them. They did not understand how spiritual care can support somatic strategies of symptom control and how both approaches are intertwined. Furthermore, they were unsure of how to assess patients’ spiritual needs. We therefore opted for the above-mentioned approach which allows lecturing relevant medical implications alongside spiritual care. As evaluations showed, this embeds spiritual care in a more clinical and tangible manner and students seem to better realize the relevance that spiritual care has in daily clinical practice. For example, students repeatedly stated that they were now able to understand the importance of ongoing collaborations for patients’ comfort care, e.g., in more sufficiently relieving anxiety or social distress.

Since this novel concept was perceived positively by medical students, we transposed it to our seminar titled “symptom control” which is now also held by a hospital chaplain and a physician. In the seminars, content from the lectures is further deepened and there is more room for discussions, e.g. concerning assessment of spiritual needs, possibilities of spiritual care, and inter-professional collaboration. There is also an emphasis on determining which patients might benefit from spiritual care making use of the SPIR tool (patient’s self-description as a S piritual person— P lace of spirituality in patient’s life – patient’s I ntegration in a spiritual community – R ole of health care professional in the domain of spirituality), which tackles different dimensions of spirituality [ 23 ].

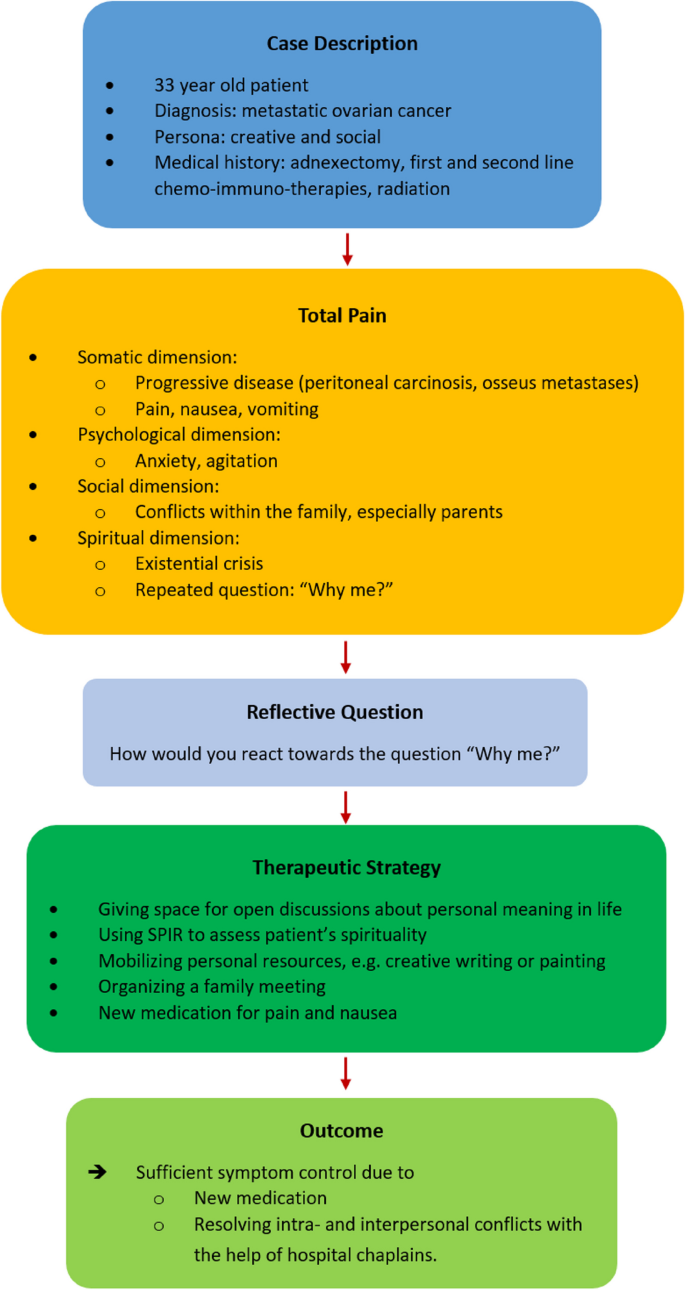

In the seminar, a 33-year-old fictitious patient (inspired by a real patient) served as an example case. Her situation is used to address strategies for symptom control on both somatic and spiritual domains. To achieve this, a reflective question is discussed with the students followed by a joint development of possible therapeutic strategies on both the somatic and spiritual domain (see Fig. 2 ).

Case discussion in the seminar

Our approach can be described as novel, since training in spiritual care often involves the mere shadowing of chaplains [ 5 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. An interprofessional, educational approach was mainly used with physicians or nurses in training [ 5 , 27 , 28 , 29 ], but not with medical students.

Evaluation methods

A structured, paper-based questionnaire was developed in repeated interdisciplinary and multi-professional discussions in the Interdisciplinary Centre for Palliative Care Medicine, University Hospital Düsseldorf, Germany. The basis for the questionnaire were the learning goals that are to be achieved within the seminar, as well as a didactic evaluation. The questionnaire was pretested among medical students, and unclear statements were altered. The questionnaire consists of two parts. The first part is made up of five statements regarding knowledge about total pain, assessing spiritual needs, and defining spiritual care (see Table 1 ) on both the knowledge and skills level. These statements cover the field of specific outcome evaluation. Making use of the comparative self-assessment (CSA) method to determine if a gain in knowledge was achieved, each student evaluated their knowledge before and after the seminar using the German school grading system (1 = “excellent” to 6 = “unsatisfactory”). The CSA gain is a well described and implemented method in evaluating actual knowledge gains in education [ 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 ]. This evaluation tool has the benefit of not taking into account experiences made beforehand as they are not contributing to the effect size [ 31 ]. CSA gain is calculated as followed:

Furthermore, CSA gain was calculated with a 95% confidence interval and standard error using individual learning gain (ILG) values. These values were calculated using the following formulas:

ILG = 0 if pre = post and

ILG = (pre − post)/(pre − 1) × 100 if pre > post [ 31 ].

The second part of the questionnaire consists of four questions regarding the perception of the seminar (structure, teaching spiritual care alongside symptom control in palliative care). A 5-Point-Likert scale was used for evaluation (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree).

Study participation and analysis

Participation in the study was anonymous, voluntary, and could be withdrawn at any time without explanation. Eligible participants were undergraduate medical students at the beginning of their fifth year of medical education (Germany: total of min. six years), who completed the mandatory palliative care course. The purpose and content of the study were presented orally, and, furthermore, written information and consent documents were handed out. After completion of the seminar, the questionnaire was handed out making use of a post-then design in which the students were asked to retrospectively rate their knowledge before and after the seminar. There were no exclusion criteria other than refusing to participate. Due to the small number of students per seminar ( n = 15–20), no demographic characteristics besides sex were assessed.

Data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2020 (version 16.42, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) and IBM SPSS Statistic version 28.0.1.1 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Throughout the course of one semester in 2023, the questionnaires were rolled out in each of six separate seminars. Out of 108 eligible attending students, 52 students participated in total (48.1%). 25% ( n = 13) of the participants were of female, 75% ( n = 39) of male sex. Within the answered questionnaires, there was no missing data.

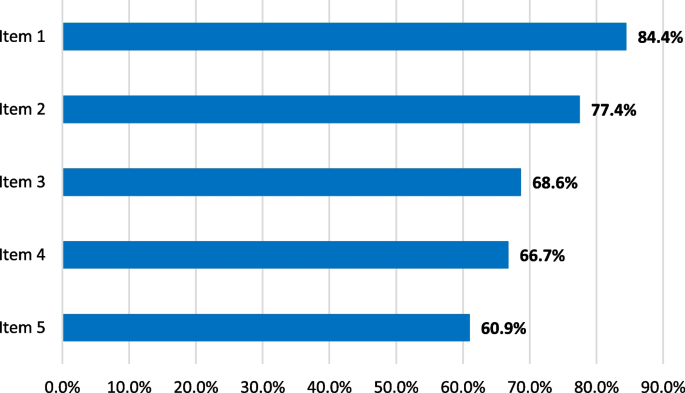

Regarding the specific outcome evaluation, CSA gains showed a relevant increase especially in the field of knowledge (see Table 2 and Fig. 3 ). The greatest improvement (84.8%) was achieved in the ability of defining total pain and realizing its importance in clinical settings (77.4%). After the seminar, medical students were increasingly able to name tools such as SPIR in order to engage in spiritual needs assessment (CSA gain 68,8%). A lower increase in knowledge was achieved in realizing how spiritual care itself can benefit patients’ needs (66.7%). The lowest gain was detected in actually identifying patients who might benefit from spiritual care (60.9%), which represents a skill to be learned rather than knowledge to be gained.

CSA gains for each item

Statistical analysis using 95% confidence intervals confirmed the gains in knowledge, which were significant for all items (Table 2 ).

In regard to the second part of the questionnaire, students were overall satisfied with the new structure of the seminar (Table 3 and Fig. 4 ). The content was comprehensible and delivered clearly gaining a mean score of 4.3 (median 4, SD 0.6, min. 2, max. 5). The content was perceived as overall relevant to the later work in medicine (mean 4.3, median 4, SD 0.6, min. 3, max. 5). It seems as if medical students regard the implementation of spiritual care education into the seminar “symptom control”, which focuses on alleviating symptoms on multidimensional levels, as expedient. They feel that implementing education on spiritual care into this seminar makes sense (mean 4.2, median 4, SD 0.8, min. 1, max. 5). Furthermore, most students do not opt for a seminar solely revolving around spiritual care (mean 2.6, median 2, SD 1.3, min. 1, max. 5).

Perception of the seminar, Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree)

Our data show that implementing spiritual care education into existing medical curricula, in our example palliative care, is feasible and well perceived among medical students. The timing of our seminar is in accordance to other studies that found that spiritual care should be implemented in mandatory undergraduate courses [ 6 ]. Students do not wish for a seminar solely revolving around spiritual care but prefer a connection to clinical practice and strategies in symptom management. This enables them to understand the relevance of spiritual care in a daily clinical setting.

To evaluate training programs, Kirkpatrick proposed a four-level approach (level 1: reaction, level 2: learning, level 3: behaviour, level 4: results) [ 35 ]. We followed levels 1 (reaction—satisfaction) and 2 (learning—gains in knowledge) making use of the conducted questionnaire. Level 3 (change in behaviour – acquired skills) was briefly addressed with item 5 in the first part of the questionnaire. As level 4 is an indicator of direct results of the training at an organizational level, we were not able to incorporate items on this level. A different study among undergraduate nursing students assessed the effectiveness of teaching spiritual care in mandatory classes: There was an increase in knowledge, e.g., in defining spirituality, compared to students who obtained no information on spiritual care [ 36 ]. This is comparable to our study, as there were gains in knowledge after completing the mandatory seminar. We reached higher individual learning gains on the knowledge level than on the skills level, as was also the case in a number of other studies we conducted [ 31 ]. This is mainly because, due to the format of the seminar, no bedside teaching takes place and scenarios that might occur in everyday clinical practice can only be discussed and serve as examples.

The concept of total pain is essential in palliative care; however, it should not only be taken into consideration in a palliative setting, but whenever patients experience high burdens on various dimensions such as pain, anxiety, grief or existential distress [ 2 , 4 , 17 , 37 , 38 ]. We were able to thoroughly educate students on total pain and its relevance in clinical settings. Spirituality plays an important role in a holistic approach. However, literature shows that HCP often don’t know how to implement spiritual assessments and how to deal with spiritual needs [ 1 , 5 , 6 , 8 ]. A systematic review on teaching methods found the usage of practical tools and the involvement of chaplains to be effective facilitators in the teaching of spiritual care [ 5 ]. A scoping review found that spiritual care should be taught in both mono- and multi-disciplinary educational settings [ 6 ]. With our multi-professional approach, we were able to introduce students to tools in assessing spiritual needs, such as SPIR [ 23 ]. Within this item, there was a definite gain in knowledge of these tools which make assessing spiritual needs of patients more feasible. This is in accordance with findings of a number other studies [ 5 ]. In our study, however, students are still unsure if they are fully able to determine which patients might actually benefit from spiritual care, even though this item still reached a learning gain of 60.9%. As concluded by other authors, there is need for ongoing education [ 5 ].

Even though our seminar entails many different aspects of the total pain concept (somatic symptom management, spirituality, and spiritual care) medical students found the content to be clearly structured and comprehensible. More importantly, they understood the relevance of spirituality for their future clinical work and perceived the multi-professional teaching as highly satisfactory. In sensitizing them in this, we hope that they keep in mind the importance of ongoing collaborations between different professions.

Our study has some limitations. Even though the questionnaire was pretested among medical students before the actual study, no validated questionnaire was used. The response rate of almost 50% is relatively low and it can be assumed that those who participated were mostly students who were interested in the topic. This might have led to bias as positive effects might have been overestimated. Due to the small study population and to protect the privacy of participating students, no demographic data besides sex was collected. Demographic data, however, might contribute to a better understanding of spirituality or palliative medicine beforehand such as age, professional expertise, or own spiritual resources. This also meant that adjusting for confounding factors was not possible. This study solely dealt with medical students and no patients were involved. It would be of interest to assess as to whether the content taught in this seminar ultimately impacts the wellbeing or stress levels of patients in everyday clinical practice. A study focusing on patients would complement the findings of this study, as suggested by other researchers [ 5 ]. Furthermore, the study was only performed in one centre; therefore, it can only serve as an example on how spiritual care education might be successfully implemented into medical curricula.

Spirituality plays an important role for many people and should always be taken into consideration when treating patients. This especially applies to palliative care where the addressing of spiritual needs is of crucial importance [ 18 ]. However, many HCP don’t know how to address topics revolving around spirituality which makes it hard to determine which patients might benefit from spiritual care. Therefore, education on the nature of spiritual care, on what it entails and on how it can support patients in everyday clinical practice should be thoroughly integrated into medical curricula. We opted to implement spirituality and spiritual care into an existing seminar and lecture within the medical curriculum at our faculty. This was well received among students. As a result, we found a clear increase in knowledge about total pain and about the tools one might use to assess spiritual needs. This knowledge needs to be further strengthened in practical clinical scenarios.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials are available within this publication.

Abbreviations

Health care professional

European Association of palliative care

- Spiritual care

Best M, Leget C, Goodhead A, Paal P. An EAPC white paper on multi-disciplinary education for spiritual care in palliative care. BMC Palliat Care. 2020;19(1):9.

Article Google Scholar