Characteristics of Office-based Physician Visits, 2018

NCHS Data Brief No. 408, May 2021

PDF Version pdf icon (592 KB)

Jill J. Ashman, Ph.D., Loredana Santo, M.D., M.P.H., and Titilayo Okeyode, M.Sc.

- Key findings

Do office-based physician visit rates vary by patient age and sex?

What was the primary expected source of payment at office-based physician visits, and did it vary by age, what were the major reasons for office-based physician visits, what services were ordered or provided at office-based physician visits, and did they vary by age, definitions, data source and methods, about the authors, suggested citation.

Data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey

- In 2018, there were an estimated 267 office-based physician visits per 100 persons.

- The visit rate among females was higher than for males, and the rates for both infants and older adults were higher than the rates for those aged 1–64.

- Private insurance was the primary expected source of payment for most visits by children under age 18 years and adults aged 18–64, whereas Medicare was the primary expected source of payment for most visits by adults aged 65 and over.

- Compared with adults, a larger percentage of visits by children were for either preventive care or a new problem.

- Compared with children, a larger percentage of visits by adults included an imaging service that was ordered or provided.

In 2018, 85% of adults and 96% of children in the United States had a usual place to receive health care ( 1 , 2 ). Most children and adults listed a doctor’s office as the usual place they received care ( 1 , 2 ). In 2018, an estimated 860.4 million office-based physician visits occurred in the United States ( 3 , 4 ). This report examines visit rates by age and sex. It also examines visit characteristics—including insurance status, reason for visit, and services—by age using data from the 2018 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS).

Keywords : ambulatory health care, insurance, NAMCS

- In 2018, there were 267 office-based physician visits per 100 persons ( Figure 1 ).

- The visit rate for both infants under age 1 year (596 per 100 infants) and adults aged 65 and over (550 per 100 adults aged 65 and over) was higher than the rate for children aged 1–17 years, (153 per 100 children aged 1–17 years), adults aged 18–44 (173 per 100 adults aged 18–44), and adults aged 45–64 (302 per 100 adults aged 45–64).

- The visit rate for adults aged 45–64 was lower than the rates for both infants and adults aged 65 and over and higher than the rates for children aged 1–17 and adults aged 18–44.

- The visit rate among females (308 visits per 100 females) was higher than the rate for males (224 visits per 100 males).

Figure 1. Visit rates, by selected demographics: United States, 2018

- Private insurance was the primary expected source of payment at one-half (50%) of all office-based physician visits, followed by Medicare (29%), Medicaid (12%), and no insurance (7%) ( Figure 2 ).

- Private insurance was the primary expected source of payment for most visits by children under age 18 years (64%) and adults aged 18–64 (67%), whereas Medicare was the primary expected source of payment for most visits by adults aged 65 and over (80%).

- Medicaid as the primary expected source of payment decreased with increasing age: 30% among under 18, 14% among 18–64, and 2% among 65 and over.

- No insurance or self-pay as the primary expected source of payment varied by age: 11% among 18–64, 3% among under 18, and 2% among 65 and over.

Figure 2. Primary expected source of payment, by age: United States, 2018

- A chronic condition was listed as the major reason for 39% of all office-based physician visits, followed by a new problem (24%), preventive care (23%), pre- or postsurgery care (8%), and an injury (6%) ( Figure 3 ).

- Compared with children, a larger percentage of visits by adults listed chronic conditions (13% compared with 38% among 18–64 and 52% among 65 and over) and pre- or postsurgery care (1% compared with 11% among 18–64 and 8% among 65 and over) as the major reason for visit.

- Preventive care as the major reason for visit decreased as age increased: 38% for under 18, 23% for 18–64, and 16% for 65 and over. This same decreasing pattern was seen for a new problem: 43% for under 18, 22% for 18–64, and 18% for 65 and over.

- The percentage of visits that listed injury as the major reason for the visit was similar by age: 5% for children and adults aged 65 and over, and 6% for adults aged 18–64.

Figure 3. Major reasons for office-based physician visits, by age: United States, 2018

- An examination or screening was ordered or provided at almost one-half (45%) of all office-based physician visits, followed by laboratory tests (24%), health education or counseling (19%), imaging (13%), and procedures (11%) ( Figure 4 ).

- A higher percentage of examinations or screenings was ordered or provided at visits by children (57%) than adults (44% for 18–64 and 42% for 65 and over), but a lower percentage of imaging services was ordered or provided at visits by children (3%) than those aged 18–64 (15%) and 65 and over (14%).

- A lower percentage of health education or counseling services was ordered or provided at visits by adults aged 65 and over (13%) compared with younger adults (20%) and children (28%), but a higher percentage of laboratory tests was ordered or provided at visits by adults aged 18–64 (26%) compared with children (18%).

- The percentage of visits with a procedure ordered or provided was similar by age: 9% for children, 10% for adults aged 18–64, and 12% for adults aged 65 and over.

Figure 4. Selected services ordered or provided at office-based physician visits, by age: United States, 2018

During 2018, the overall rate of office-based physician visits was 267 visits per 100 persons. The visit rate for infants and older adults was higher than the rate for other age groups. The visit rate for females was higher than the rate for males. Most visits by children (64%) and adults aged 18–64 (67%) listed private insurance as the primary expected source of payment, whereas most visits by older adults listed Medicare as the primary expected source of payment (80%). Approximately 7% of office-based physician visits were made by those with no insurance. A higher percentage of visits by adults aged 18–64 (11%) had no insurance compared with adults aged 65 and over (2%) and children (3%). A chronic condition was the major reason for 39% of all office-based physician visits, and visits for chronic conditions were higher among adults than children. A higher percentage of visits by children than adults were for a new problem or preventive care, whereas the reverse was true for visits related to pre- or postsurgery care. Almost one-half (45%) of all office-based physician visits included an examination or screening that was ordered or provided. Compared with adults aged 65 and over, a higher percentage of visits by children and younger adults included health education or counseling. Compared with children, a higher percentage of visits by adults included imaging services.

Major reason for this visit : A variable was created by merging the “INJURY” variable with the provider-assessed major reason for this visit ( 5 ). Injury was given preference over all other reasons. The five categories for major reason for this visit included:

- Chronic condition: A visit primarily to receive care or examination for a preexisting chronic condition or illness (onset of condition was 3 months or more before this visit). Includes both routine visits and flare-ups; a visit primarily due to a sudden exacerbation of a preexisting chronic condition.

- Injury: A visit defined as injury or poisoning related, based on any listed reason for visit and diagnosis ( 5 ). In 2018, the definition of injury used the I nternational Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision , Clinical Modification to code injury and poisoning diagnoses.

- New problem: A visit for a condition or illness having a relatively sudden or recent onset (within 3 months of this visit).

- Pre- or postsurgery: A visit scheduled primarily for care required prior to or following surgery (e.g., presurgery tests or removing sutures).

- Preventive care: General medical examinations and routine periodic examinations. Includes prenatal care, annual physicals, well-child examinations, screening, and insurance examinations.

Selected services : Services that were ordered or provided during the sampled visit for the purpose of screening (i.e., early detection of health problems in asymptomatic individuals) or diagnosis (i.e., identification of health problems causing individuals to be symptomatic) are included ( 5 ). Each selected service item was grouped into five categories:

- Examinations or screenings: Includes alcohol misuse, breast, depression, domestic violence, foot, neurologic, pelvic, rectal, retinal or eye, skin, and substance misuse.

- Health education or counseling: Includes alcohol abuse counseling, asthma, asthma action plan given to patient, diabetes education, diet or nutrition, exercise, family planning or contraception, genetic counseling, growth or development, injury prevention, sexually transmitted disease prevention, stress management, substance abuse counseling, tobacco use or exposure, and weight reduction.

- Imaging services: Includes bone mineral density, CT scan, echocardiogram, ultrasound, mammography, MRI, and X-ray.

- Laboratory tests: Includes basic metabolic panel, complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, creatinine or renal function panel, culture (blood, throat, urine, or other), glucose, chlamydia test, gonorrhea test, HbA1c, hepatitis testing, HIV test, human papillomavirus DNA test, lipid profile, liver enzymes or hepatic function panel, pap test, pregnancy or HCG test, prostate-specific antigen, rapid strep test, thyroid-stimulating hormone or thyroid panel, urinalysis, and vitamin D test.

- Procedures: Includes audiometry, biopsy, cardiac stress test, colonoscopy, cryosurgery or destruction of tissue, EKG or ECG, electroencephalogram, electromyogram, excision of tissue, fetal monitoring, peak flow, sigmoidoscopy, spirometry, tonometry, tuberculosis skin testing, and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

Data for this report are from NAMCS, which is conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics. NAMCS is an annual, nationally representative survey of office-based physicians and visits to their practices ( 3 , 5 ). The target universe of NAMCS is physicians classified as providing direct patient care in office-based practices. Radiologists, anesthesiologists, and pathologists are excluded, as are physicians in community health centers. The 2018 sample consisted of 2,999 physicians. Participating physicians provided 9,953 visit records. The participation rate—the percentage of in-scope physicians for whom at least one visit record was completed—was 35.2%. The response rate—the percentage of in-scope physicians for whom at least one-half of their expected number of visit records was completed—was 31.1%. An iterative proportional fitting procedure was used to adjust NAMCS weights for nonresponse bias ( 5 ).

Data analyses were performed using the statistical packages SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.) and SAS-callable SUDAAN version 11.0 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, N.C.). Differences in the distribution of selected characteristics of office-based physician visits were based on chi-square tests ( p < 0.05). If a difference was found to be statistically significant, additional pairwise tests were performed. Statements of difference in paired estimates were based on two-tailed t tests with statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level. Terms such as “higher” or “lower” indicate that the differences were statistically significant.

Jill J. Ashman, Loredana Santo, and Titilayo Okeyode are with the National Center for Health Statistics, Division of Health Care Statistics.

- Black LI, Benson V. Table C-7a. Age-adjusted percentages (with standard errors) of having a usual place of health care, and age-adjusted percent distributions of type of place, for children under age 18 years, by selected characteristics: United States, 2018. Tables of Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Children: 2018 National Health Interview Survey pdf icon . National Center for Health Statistics. 2019.

- Villarroel MA, Blackwell DL, Jen A. Table A-16a. Age-adjusted percent distributions (with standard errors) of having a usual place of health care and of type of place, among adults aged 18 and over, by selected characteristics: United States, 2018. Tables of Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Adults: 2018 National Health Interview Survey pdf icon . National Center for Health Statistics. 2019.

- National Center for Health Statistics. 2018 NAMCS micro-data file. 2021.

- Santo L, Okeyode T. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2018 National Summary Tables. National Center for Health Statistics. 2021. [Forthcoming].

- National Center for Health Statistics. 2018 NAMCS micro-data file documentation. 2021.

Ashman JJ, Santo L, Okeyode T. Characteristics of office-based physician visits, 2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 408. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2021. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:105509 external icon .

Copyright information

All material appearing in this report is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission; citation as to source, however, is appreciated.

National Center for Health Statistics

Brian C. Moyer, Ph.D., Director Amy M. Branum, Ph.D., Acting Associate Director for Science

Division of Health Care Statistics

Carol J. DeFrances, Ph.D., Acting Director Alexander Strashny, Ph.D., Associate Director for Science

- Get E-mail Updates

- Data Visualization Gallery

- NHIS Early Release Program

- MMWR QuickStats

- Government Printing Office Bookstore

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- Health, Pharma & Medtech ›

- Health Professionals & Hospitals

U.S. physicians - statistics & facts

How much are u.s. physicians paid, compensation for services depends on the payer, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Total active physicians in the U.S. 2024, by state

Physicians in patient care in the U.S. 1975-2019

Number of active physicians in the U.S. 2024, by specialty area

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Healthcare Professionals

Active physicians in the U.S. 1975-2019

Primary care physicians in the U.S. in 2019, by gender and specialty

Top U.S. states by number of active physicians 2019

Further recommended statistics

- Basic Statistic Number of active physicians in the U.S. 2024, by specialty area

- Basic Statistic Number of physicians in the U.S. by specialty and gender 2021

- Premium Statistic Active physicians in the U.S. 1975-2019

- Premium Statistic Physicians in patient care in the U.S. 1975-2019

- Premium Statistic Primary care physicians in the U.S. in 2019, by gender and specialty

- Premium Statistic Number of office-based, direct patient care physicians in the US 2019, by specialty

- Premium Statistic Number of office-based primary care physicians in the US 2019, by specialty

Number of active physicians in the U.S. in 2024, by specialty area

Number of physicians in the U.S. by specialty and gender 2021

Number of active physicians in the U.S. in 2021, by specialty and gender

Active physicians per 10,000 civilian population in the U.S. from 1975 to 2019*

Physicians in patient care per 10,000 civilian population in the U.S. from 1975 to 2019*

Distribution of primary care physicians in the United States in 2019, by gender and specialty

Number of office-based, direct patient care physicians in the US 2019, by specialty

Number of office-based, direct patient care physicians in the United States in 2019, by specialty

Number of office-based primary care physicians in the US 2019, by specialty

Number of office-based, direct patient care physicians dispensing primary care in the United States in 2019, by specialty

U.S. states

- Premium Statistic Total active physicians in the U.S. 2024, by state

- Basic Statistic Leading U.S. states based on the total number of active physicians 2024

- Premium Statistic Leading U.S. states by number of active primary care physicians 2024

- Basic Statistic Leading U.S. states by number of active specialist physicians 2024

- Premium Statistic Top U.S. states by number of active physicians 2019

- Premium Statistic Top U.S. states by number of physicians in patient care 2019

Total number of active physicians in the U.S., as of January 2024, by state

Leading U.S. states based on the total number of active physicians 2024

Leading 10 U.S. states based on the total number of active physicians as of 2024

Leading U.S. states by number of active primary care physicians 2024

Leading 10 U.S. states based on the number of active primary care physicians as of 2024

Leading U.S. states by number of active specialist physicians 2024

Leading 10 U.S. states based on the number of active specialist physicians as of 2024

Leading 10 U.S. states by number of active physicians per 10,000 civilian population in 2019*

Top U.S. states by number of physicians in patient care 2019

Leading 10 U.S. states by number of physicians in patient care per 10,000 civilian population in 2019*

Expenditure

- Premium Statistic U.S. physician and clinical services expenditure 1960-2022

- Premium Statistic Physician and clinical services spending in the U.S. 2012-2022, by payer

- Basic Statistic U.S. consumer price index: physician and dental services 1960-2022

U.S. physician and clinical services expenditure 1960-2022

Physician and clinical services expenditure in the United States in selected years from 1960 to 2022 (in billion U.S. dollars)

Physician and clinical services spending in the U.S. 2012-2022, by payer

Physician and clinical services expenditure in the United States from 2012 to 2022, by payer

U.S. consumer price index: physician and dental services 1960-2022

Consumer price index for physician and dental services in the U.S. from 1960 to 2022

Compensation

- Basic Statistic Annual compensation of U.S. physicians by specialty 2024

- Basic Statistic Physician pay change in 2024, by specialty

- Basic Statistic Average U.S. physician compensation in 2024, by region

- Basic Statistic Top U.S. states by annual compensation for physicians 2023

- Basic Statistic Annual compensation earned by U.S. physicians 2024, by gender

- Basic Statistic Share of U.S. physicians who felt fairly paid 2024, by specialty

- Basic Statistic Use of signing bonuses as incentive for the recruitment of U.S. physicians 2016-2021

Annual compensation of U.S. physicians by specialty 2024

Average annual compensation earned by U.S. physicians as of 2024, by specialty (in 1,000 U.S. dollars)

Physician pay change in 2024, by specialty

Percentage physician compensation increase in select medical specialties in the U.S. as of 2024

Average U.S. physician compensation in 2024, by region

Average annual physician compensation in the United States as of 2024, by region (in 1,000 U.S. dollars)

Top U.S. states by annual compensation for physicians 2023

Top 10 U.S. states by annual compensation for physicians as of 2023 (in U.S. dollars)*

Annual compensation earned by U.S. physicians 2024, by gender

Annual compensation earned by male and female physicians in the U.S. as of 2024, by type of physician (in U.S. dollars)

Share of U.S. physicians who felt fairly paid 2024, by specialty

Percentage of U.S. physicians who felt fairly compensated as of 2024, by specialty

Use of signing bonuses as incentive for the recruitment of U.S. physicians 2016-2021

Use of signing bonuses as incentive for the recruitment of physicians in the U.S. from 2004/2005 to 2020/2021

- Basic Statistic Burnout among U.S. physicians as of 2023, by gender and age

- Basic Statistic Percentage of U.S. physicians feeling burned out by specialty 2019-2020

- Premium Statistic Major causes for burn-out among U.S. physicians 2020

- Basic Statistic Share of U.S. physicians that would recommend medicine careers to younger people 2023

Burnout among U.S. physicians as of 2023, by gender and age

Percentage of physicians in the U.S. that have frequent feelings of burnout as of 2023, by gender and age group

Percentage of U.S. physicians feeling burned out by specialty 2019-2020

Percentage of physicians feeling burned out in the U.S. in 2019 and 2020, by specialty

Major causes for burn-out among U.S. physicians 2020

Major causes for burn-out among U.S. physicians as of 2020

Share of U.S. physicians that would recommend medicine careers to younger people 2023

Share of physicians in the U.S. that would recommend medicine as a career to young people from 2014 to 2023

- Basic Statistic Share of U.S. physicians who experienced select changes due to COVID-19, 2020-2021

- Basic Statistic Share of U.S. physicians affected by COVID-19 in select ways, August 2020

- Basic Statistic Share of U.S. physicians frustrated by COVID-19 regulation non-compliance, Aug. 2020

- Basic Statistic Estimated loss of revenue among U.S. physicians due to COVID-19 as of July 2020

Share of U.S. physicians who experienced select changes due to COVID-19, 2020-2021

Percentage of U.S. physicians who experienced select changes as a result of COVID-19 in July 2020 and June 2021

Share of U.S. physicians affected by COVID-19 in select ways, August 2020

Percentage of U.S. physicians who had select experiences due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on their practice or professional employment, August 2020

Share of U.S. physicians frustrated by COVID-19 regulation non-compliance, Aug. 2020

Percentage of U.S. physicians frustrated by lack of population compliance with COVID-19 distancing and mask-wearing protocols as of August 2020, by gender

Estimated loss of revenue among U.S. physicians due to COVID-19 as of July 2020

Estimated revenue losses due to COVID-19 among independent physician practices in the United States as of July 2020 (in billion U.S. dollars)*

Further reports

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

- Physicians in the U.S.

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

- Doctors' consultations

Related topics

This indicator presents data on the number of consultations patients have with doctors in a given year. Consultations with doctors can take place in doctors’ offices or clinics, in hospital outpatient departments or, in some cases, in patients’ own homes. Consultations with doctors refer to the number of contacts with physicians, both generalists and specialists. There are variations across countries in the coverage of different types of consultations, notably in outpatient departments of hospitals. The data come from administrative sources or surveys, depending on the country. This indicator is measured per capita.

Latest publication

- Child vaccination rates

- Influenza vaccination rates

- Length of hospital stay

- Hospital discharge rates

- Computed tomography (CT) exams

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) exams

- Caesarean sections

Doctors' consultations Source: Health care utilisation

- Selected data only (.csv)

- Full indicator data (.csv)

- Add this view

- Go to pinboard

©OECD · Terms & Conditions

Perspectives

Highlight countries.

Find a country by name

Currently highlighted

Select background.

- European Union

latest data available

Definition of Doctors' consultations

Last published in.

Please cite this indicator as follows:

Related publications

Source database, further indicators related to health care use, further publications related to health care use.

Your selection for sharing:

- Snapshot of data for a fixed period (data will not change even if updated on the site)

- Latest available data for a fixed period,

- Latest available data,

Sharing options

Permanent url.

Copy the URL to open this chart with all your selections.

Use this code to embed the visualisation into your website.

Width: px Preview Embedding

- Open access

- Published: 10 May 2024

The role of perceived quality of care on outpatient visits to health centers in two rural districts of northeast Ethiopia: a community-based, cross-sectional study

- Mohammed Hussien 1

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 614 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

24 Accesses

Metrics details

Patients who have had a negative experience with the health care delivery bypass primary healthcare facilities and instead seek care in hospitals. There is a dearth of evidence on the role of users’ perceptions of the quality of care on outpatient visits to primary care facilities. This study aimed to examine the relationship between perceived quality of care and the number of outpatient visits to nearby health centers.

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in two rural districts of northeast Ethiopia among 1081 randomly selected rural households that had visited the outpatient units of a nearby health center at least once in the previous 12 months. Data were collected using an interviewer-administered questionnaire via an electronic data collection platform. A multivariable analysis was performed using zero-truncated negative binomial regression model to determine the association between variables. The degree of association was assessed using the incidence rate ratio, and statistical significance was determined at a 95% confidence interval.

A typical household makes roughly four outpatient visits to a nearby health center, with an annual per capita visit of 0.99. The mean perceived quality of care was 6.28 on a scale of 0–10 (SD = 1.05). The multivariable analysis revealed that perceived quality of care is strongly associated with the number of outpatient visits (IRR = 1.257; 95% CI: 1.094 to 1.374). In particular, a significant association was found for the dimensions of provider communication (IRR = 1.052; 95% CI: 1.012, 1.095), information provision (IRR = 1.088; 95% CI: 1.058, 1.120), and access to care (IRR = 1.058, 95% CI: 1.026, 1.091).

Conclusions

Service users’ perceptions of the quality of care promote outpatient visits to primary healthcare facilities. Effective provider communication, information provision, and access to care quality dimensions are especially important in this regard. Concerted efforts are required to improve the quality of care that relies on service users’ perceptions, with a special emphasis on improving health care providers’ communication skills and removing facility-level access barriers.

Peer Review reports

Essential health service coverage, which is one of the two dimensions of universal health coverage, is also an indicator of progress towards sustainable development goals. The goal of the service coverage dimension of universal health coverage is that people in need of health services receive them and that the services received are of sufficient quality to achieve potential health gains [ 1 ].

Despite various efforts put in place as part of the main global agenda to facilitate access and effective coverage, persistent inequalities in accessing and using essential health services exist both between and within countries [ 2 ]. A recent global estimate showed that the excess deaths of 3·6 million people in low- and middle-income countries were due to the non-utilization of health care [ 3 ]. Essential health service coverage involves receiving a wide range of promotive, preventative, curative, rehabilitative, and palliative health services [ 2 ]. Outpatient visits with primary care providers are for many people the most frequent contact with health services, and often provide an entry point for subsequent health care [ 4 ]. Outpatient service use, which is measured by the number of outpatient visits per person per year, is one of the proposed core indicators for health care delivery [ 5 ]. The use of outpatient services can be used as a proxy for essential services coverage and portray the image of the health care system. Low rates of outpatient visits are suggestive of limited access and low quality of care [ 6 ].

There has been an increasing emphasis on the importance of improving health-care quality as a critical component of the path to universal health coverage, along with expanding service coverage and financial risk protection [ 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Low-quality health services, despite their availability, are a major deterrent to achieving effective universal health coverage. This is due to the fact that communities will not use services that they distrust and are of little benefit to them [ 7 ]. In line with the global trend, the health system in Ethiopia has shifted its focus from increasing coverage of essential health services to quality improvement. Parallel to expanding access to services, the Ministry of Health identified five priority areas in its strategic plan that require radical shifts, one of which is transformation in quality of care [ 10 ].

Quality of health care is a broad concept that has been assessed using various measurement approaches in order to better understand it [ 11 ]. The emphasis on measuring healthcare quality has shifted away from the perspectives of healthcare providers towards people-centered approaches that rely on user perceptions [ 12 ]. Patients’ perceptions of health-care quality, which are based on a combination of patient experiences, rumor, and processed information, are becoming an important component of quality measurement because they are significant drivers of healthcare utilization [ 11 ].

The literature supports the view that a positive experience with healthcare services would prompt patients to revisit the healthcare facility [ 13 , 14 , 15 ] and attend for scheduled appointments [ 16 ]. This is based on the view that patients with negative health-care delivery experiences will lose trust in service providers, and they will be less likely to use services once more [ 17 , 18 ]. It was also documented that a greater number of problems related to the quality of primary care provisions, as perceived by users, discourages the use of health care [ 19 ]. The perception of the quality of care also has an effect on the choice of healthcare facility. Evidence indicated that patients who had little faith in primary health care facilities sought treatment elsewhere, preferably in hospitals [ 20 ]. Service users with a positive experience with care delivery also recommend the service provider to others. A nationally representative survey conducted in 14 low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries showed that high ratings of user-reported quality of care is a positive predictor of patients’ recommendations of the healthcare facility to a friend or family member [ 21 ].

The quality of healthcare must be assessed and improved on a regular basis to foster optimum health care utilization and health outcomes. A recent study in Ethiopia investigated the perceived quality of medical services at public hospital outpatient units [ 22 ]. However, the quality of outpatient services in primary health care facilities is not well addressed from the perspective of the service users. Furthermore, while some studies looked at the effect of perceived quality of care on behavioral intentions [ 13 , 14 , 15 ] and the choice of health facility levels [ 20 , 23 ], there is little scientific evidence on the relationship between perceived quality of care in primary care facilities and the frequency of outpatient visits in the same facility. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to examine the association between service users’ perceptions of the quality of care and the number of outpatient visits to nearby health centers among households in two rural districts of Ethiopia.

Improving the quality of health care is among the top priorities of Ethiopia in its health sector strategic plan [ 10 ]. The findings of this study will inform health authorities, service providers, and other relevant actors on the role of service users’ perceptions of the quality of care in their choice of health facility, which can be a proxy for the performance of the larger health system. It will also provide useful information to identify areas of focus that require the attention of relevant stakeholders striving to improve the quality of care.

Study design and setting

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in rural parts of two neighboring districts in northeast Ethiopia, Kalu and Tehulederie. Kalu has nine health centers serving a population of around 235,000, of which 89% live in rural areas. In Tehulederie, there are five health centers and one primary hospital designated to provide services for a population of more than 145,000, of which 88% are rural dwellers [ 24 ].

In Ethiopia, health services are provided by a network of health facilities arranged in a three-tier health care delivery model: primary healthcare units, general hospitals, and specialized hospitals. A primary healthcare unit consists of health posts, health centers, and primary hospitals. A health center is attached to five satellite health posts to provide both preventive and curative services to approximately 25,000 people, while a health post delivers preventive, promotional, and selected curative interventions at the community level. Health centers are assumed to be the first level of outpatient service delivery points in the three-tier system. Primary and general hospitals both offer inpatient and outpatient services, but to varying degrees. The third-tier system includes a specialized hospital dedicated to providing tertiary-level health care. The population is free to choose between health care facilities without being constrained by a gatekeeping policy; however, patients are encouraged to use the lower-level health facility first before proceeding to the next higher level via upward referral [ 10 ].

Sample size and sampling

The data used in this study comes from a research project examining the sustainability of a community health insurance (CHI) scheme in Ethiopia. As part of this project, a sample size of 1257 was calculated for a companion article [ 25 ], of which 1081 eligible households took part and provided complete data relevant to the current study. The study population of interest consisted of rural households that had been enrolled in the CHI scheme. This includes households that were active members at the time of the study and those that dropped out of the scheme. Households that had not visited health centers for outpatient services in the 12 months period prior to the study were excluded to minimize recall bias in measuring the perceived quality of care.

A three-level multistage sampling was used to recruit study participants. First, 12 clusters of Kebeles organized around a health center catchment area were selected. Then, 14 rural Kebeles were drawn at random proportional to the number of Kebeles under each cluster. Accordingly, nine Kebeles from Kalu and five from Tehulederie were included. A list of households that have ever been enrolled in the CHI was obtained from each Kebele’s membership registration logbook. Using random number generator software, the required sample was generated randomly from each Kebele , proportional to the number of households that have been enrolled in the scheme.

Data collection and variables

The data were collected from February 4 to March 21, 2021, through face-to-face interviews with household heads at their homes using a structured questionnaire via an electronic data collection platform. Data was collected on characteristics of the household head, including age, gender, current marital status, and educational attainment. Data was also collected on place of residence, family size, economic status, household CHI membership status, presence of chronic illness in the household, perceived health status of the household, perception of the quality of health care received from the nearby health center, and number of outpatient visits to the nearby health center by any member of the household (see Supplementary file). The data collectors submitted the completed forms to a data aggregating server on a daily basis, allowing us to review them and simplify the supervision process. Health extension workers assisted data collectors in tracking the sampled households because they are primarily responsible for providing home-based health services in rural areas and are familiar with each household’s location.

The outcome variable of interest is the number of outpatient visits to nearby health centers. It refers to a household’s outpatient trips to a nearby health center for curative health care in the year preceding the study. It is a count data with all observations greater than zero because households that had not used health care in the previous 12 months prior to data collection were excluded from the study. This was done to reduce recall bias on some of the items designed to measure perceived quality of care. Per capita outpatient visit, which is the average number of outpatient visits to nearby health center made by a household member during the one-year period preceding the study, was also calculated to allow comparison across covariates.

The number of outpatient visits was assumed to be influenced by the perceived quality of care and other household characteristics, which were included as covariates. The perceived quality of care, which is the main independent variable of interest, was assessed using a 17-item scale developed following a thorough review of validated tools for outpatient visit encounters in low- and middle-income settings including Ethiopia [ 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ]. Respondents were asked to rate how much they agreed on a set of items relating to their experiences with health services received in the outpatient departments of a nearby health center, which is thought to be the usual source of health care. Each item was designed with a 5-point response format, with 1 representing strongly disagree, 2 disagree, 3 neutral, 4 agree, and 5 strongly agree.

To allow for comparisons of summary scores of overall perceived quality of care, quality dimensions, and measurement items on a common scale, the 5-point response was converted to scores of 0, 2.5, 5.0, 7.5 and 10 respectively, and mean scores were arithmetically transformed to a continuous scale of 0 to 10 [ 31 , 32 ]. A mean score of the overall perceived quality of care was calculated from the total items and was handled as a continuous variable. The scores for the 17 items were translated into five quality dimensions using exploratory factor analysis. A mean score is also computed for each dimension based on the items that load in that dimension.

The covariates in this study are based on Anderson’s behavioral model of health service use, which contends that people’s use of health services is driven by their predisposition, enabling factors to access services, and their needs for care [ 33 ]. Based on this framework, the following characteristics were considered to control for potential confounding factors in the association between perceived quality of care and choice of health facility for outpatient visits: predisposing characteristics (age, gender, marital status, educational attainment, place of residence, and household size); enabling factors (wealth index and health insurance coverage); and the need for care (chronic illness and perceived health status).

The wealth index was created using the principal component analysis method. The scores for 15 different types of assets were converted into latent factors, and a wealth index was generated using the first factor that explained most of the variations. Based on the index, the study households were categorized into three wealth tertiles: poor, middle, and rich. Perceived health status was rated as poor, moderate, or good based on a household head’s subjective assessment of the household’s health status.

The questionnaire was pre-tested on 84 randomly selected participants prior to data collection. A cognitive interview on selected items was conducted as part of the pre-test with eight respondents using the verbal probe method to determine whether the items and response categories were well understood and interpreted by the potential respondents. As a result, six quality measurement items were removed and the wording of some items was modified on the translated local language.

Data analysis

Stata Statistical Software, release 17 was used to analyze the data. The validity of the measurement scale on perceived quality of care was assessed using exploratory factor analysis. The details on the factor analysis procedures and its results are thoroughly described in another companion article [ 34 ].

Since the outcome variable of interest is a count data, that is the annual number of outpatient visits made by the household, Poisson regression was considered as a standard analysis model. Because the number of outpatient visits is a count response variable with all observations greater than zero, the analysis would employ either zero-truncated Poisson regression (ZTP) or zero-truncated negative binomial (ZTNB) regression models. Poisson model assumes that the variance is equal to the mean. A test of goodness of fit was performed and it showed an overdispersion (the variance of outpatient visits was more than twice its mean). The Negative Binomial model is appropriate when the dependent variable is over-dispersed [ 35 ]. In addition, the Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) statistics were computed to select the best fitted model. Accordingly, the values of the AIC, BIC and DIC statistics of the zero-truncated negative binomial model were substantially lower than those of the zero-truncated Poisson model, indicating a better fit to run the multivariable regression analysis.

The basic Poisson model is given by a regression equation of the form [ 36 ],

where β 0 is the intercept, β 1 , β 2 ,. . β i are the Poisson regression coefficients of i explanatory variables whose values are at X 1 , X 2 …, X i , and, r is the incidence rate.

When interpreting results, it is preferable to use the incidence rate ratio (IRR) rather than the regression coefficients to investigate the effect of predictor variables on the count response variable. By taking the exponent of the coefficient, we obtain the incidence rate ratio (IRR) as follows,

The estimated IRR for the individual covariate \({x}_{j}\) is defined as:

where \({\widehat{\beta }}_{j}\) is the j th estimated regression coefficient.

After adjusting for the confounding effect of covariates, the measures of association estimated the association between the perceived quality of care and annual number of outpatient visits. The existence of a statistically significant association was determined at p -values of < 0.05. The degree of the association was assessed using incidence rate ratio (IRR), and their statistical significance was determined at a 95% confidence interval. In the multivariable regression analysis, two models were estimated. Model I demonstrated the association between overall perceived quality of care and the number of outpatient visits, whereas Model II showed the link between the dimensions of perceived quality of care and the number of outpatient visits, both after controlling for covariates.

Background characteristics of the study participants

The study included 1081 participants who had visited a health center at least once in the previous 12 months. The study participants’ average age was 49.25 years, with slightly more than half (51.3%) between the ages of 45 and 64, and 12.7% being 65 and older. among the total study participants, 938 (86.8%) were male, and 1003 (92.8%) were currently married. One-fifth of the study participants (20.9%) had a formal education, and 62.7% had a household size of five or above.

Nearly nine out of ten households (87.1%) were active members of the CHI scheme at the time of the study. A quarter of households (25.7%) had one or more individuals with a known chronic illness who had been informed by a healthcare provider. One-third of respondents (33.6%) rated their household health status as good, while 511 (47.3%) and 207 (19.1%) rated it as moderate and poor, respectively (Table 1 ).

Perceptions of the quality of care

The exploratory factor analysis extracted five dimensions of quality of care: technical care, patient-provider communication, information provision, access to care, and trust in care providers. On a scale of 0–10, the mean score of the overall perceived quality of care was 6.28 (SD = 1.05). Provider communication had the highest mean score (M = 7.23, SD = 1.27) of the five quality dimensions, while information provision had the lowest score (M = 5.58, SD = 1.73). The mean score of the quality dimensions and each measurement item is displayed by Table 2 .

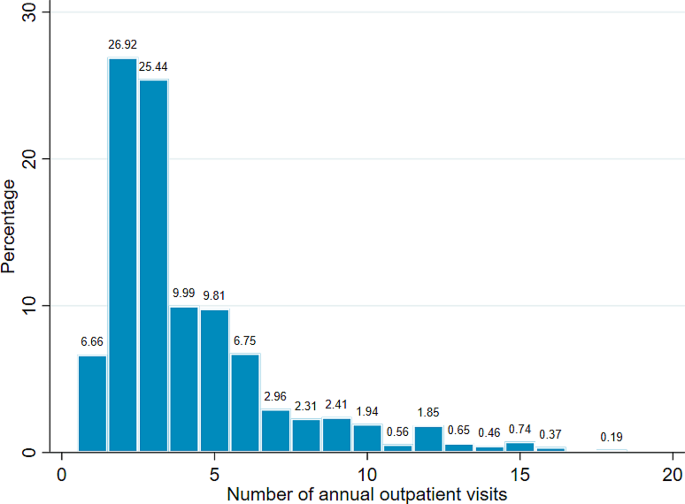

Frequency of annual outpatient visits

Frequency distribution of outpatient visits showed that more than half of the study households (52.4%) had two or three outpatient visits per year, with other counts having a smaller percentage. The maximum distribution of outpatient visits was 18 visits (0.2%) over one year. A typical household makes roughly four outpatient visits to health centers per year. The variance of outpatient visits was 8.47, which was slightly more than twice the mean of 4.10, indicating data overdispersion. Figure 1 depicts the frequency distribution of outpatient visits. Health-care utilization as measured by the number of outpatient visits per household member was 0.99 visits per person per year. Table 1 presents the per capita outpatient visits across different respondent characteristics.

Frequency distribution of outpatient visits (number of observations = 1081)

Multivariable analysis using zero-truncated negative binomial regression model

The results of the multivariable zero-truncated negative binomial regression are presented in Table 3 . In model I, the overall perceived quality of care was included in the regression analysis after adjusting for the confounding effect of the covariates. Accordingly, a positive perception of the quality of care is significantly associated with an increase in the annual number of outpatient visits. As the mean score of perceived quality of care increased by one unit, the number of outpatient visits to a nearby health center increased by 25.7% (95% CI: 1.210, 1.306; p < 0.001).

Model II included the five quality of care dimensions while controlling for the confounding effect of covariates. Three quality dimensions, namely provider communication, information provision, and access to care, were found to be significantly correlated to the number of outpatient visits. The number of outpatient visits increases by a factor of 1.052 as the mean score of provider communication rises by one unit (95% CI: 1.012, 1.095; p = 0.011). For a one-point increase in the mean score of the information provision and access to care dimensions, the number of outpatient visits increases by a factor of 1.088 and 1.058, respectively (95% CI: 1.058, 1.120; p < 0.001 and 95% CI: 1.026, 1.091; p < 0.001).

Among the covariates, age of the household head, CHI membership status, wealth index, existence of chronic illness, and perceived health status were significantly associated with the number of outpatient visits, as shown in Model II. Outpatient visits are 1.275 and 1.156 times higher in households headed by individuals aged 65 + and 45 to 64 years, respectively, compared to those headed by individuals aged 25 to 44 years (95% CI: 1.123, 1.446; p < 0.001 and 95% CI: 1.058, 1.264; p = 0.001). Similarly, the number of outpatient visits for rich households is reduced by 17.5% compared to those who belong to poor households (95% CI: 0.716, 0.950; p = 0.008). Households that were active members of CHI at the time of the study had 1.199 times the number of outpatient visits as previous members (95% CI: 1.057, 1.360; p = 0.00).

With respect to health status, the number of outpatient visits among households that had a chronic illness in their family increased by 18.3% compared to those without a chronic illness (95% CI: 1.080, 1.296; p < 0.001). Furthermore, the number of outpatient visits among households that rated their health status as good and moderate was lower by 30.8% and 23.1%, respectively, compared to those who rated it as fair (95% CI: 0.617, 0.777; p < 0.001 and 95% CI: 0.694, 0.852; p < 0.001).

This study examined how the perception on quality of care relate to the number of outpatient visits in the nearby health centers among households. According to the findings, a typical household makes about 4.10 outpatient visits to nearby health centers per year. Health care utilization, as measured by the number of outpatient visits per household member, was 0.99 visits per person per year. This is lower than the findings of a previous study in Ethiopia, which reported outpatient visits of 1.77 per person per year [ 37 ]. This could be due to differences in measurement of the outcome variable. Outpatient visits in the previous study refers to the number of health facility visits made by a household for any type of health services, including curative, follow-up, and health promotion services, in any health facility during a one-month period preceding the study, whereas in the current study, it refers to the number of outpatient visits to a nearby health center made by a household for curative health services during the 12-month period prior to the study.

The findings demonstrated that the perception on the quality of outpatient service was a predictor of the number of annual outpatient visits. This is consistent with other studies which support the view that positive experience with healthcare service would prompt patients to revisit the service provider [ 13 , 14 , 15 ] and attend for scheduled appointments [ 16 ]. It was also documented that a greater number of problems related to the quality of primary care provisions, including issues related to access, continuity of care, provider communication and coordination, as perceived by users, was negatively associated with health care utilization [ 19 ]. A systematic review identified that perceived poor quality of care pushed patients away from the lower-level health facilities, because they did not trust primary level facilities to address their basic health needs [ 20 ]. It was also indicated that the better the perceived quality of care of a health facility, the more likely that facility being chosen [ 23 , 38 , 39 ], and the belief that the health system works well and only requires minor changes was associated with having a usual source of care [ 40 ]. Moreover high ratings of user-reported quality of care is a positive predictor of patients recommendation of the healthcare facility to a friend or family member [ 21 ].

As for the linkage between the number of outpatient visits and the different perceived quality of care dimensions, a significant association was found for the provider communication, information provision, and access to care dimensions. Previous work has indicated to the positive impact of the provider-patient interaction dimension of health care quality on patients’ loyalty [ 41 ]. The assurance dimension of perceived quality of care, which refers to care providers’ knowledge and courtesy, and their ability to inspire trust and confidence has a positive effect on use of outpatient services [ 42 ] as well as behavioral intentions of patients [ 14 ]. Likewise, the empathy dimension of perceived quality of care showed a significant association with the use of outpatient services [ 42 ]. This involves the attention given to clients by service providers, including ease of making relationships, good communication and understanding their needs. Effective provider communication is a fundamental clinical skill that facilitates the establishment of a relationship of trust between the health care provider and the patient, contributing to an increase in the prestige of the medical unit and the growing interest of patients in it [ 43 ].

Provision of information to patients has an important bearing on repeated visits of a health facility. Users’ perception on the quality dimension that related to physician description of illness, causes, and treatment plan has a positive effect on the outpatients’ choice of health facility [ 23 ]. A study reported a strong association between providers’ information provision and patient’s stated intent to return [ 44 ]. That means the caregivers showed an intent to return to the same facility if the provider told them the child’s illness, and the symptoms that would indicate a need for immediate return to the facility, discussed a return visit, and counselled them on feeding the child. Similarly, information and communication dimension, which refers to providing timely information to the clients, listening to their problems carefully and proper counselling by care providers has a positive influence on behavioural intention [ 45 ].

In support of the importance of communication and information provision dimensions, a study documented that patients’ recommendation of the physician to their family and friends was influenced by their perceptions of physicians’ communications, which include asking probing questions, listening to patients’ problems without interruptions, giving sufficient time to patients to explain their problems, clarifying their doubts and advising them on future course of action by doctors [ 46 ].

Access to care is another quality dimension that is associated with outpatient visits of health centers. This includes availability of essential medicines, reasonable waiting time, fair treatment of patients and friendly approach of facility assistants. In support if this finding, another study showed that increased waiting time decreases the probability of a health facility choice [ 47 ]. It is also documented that household’s healthcare utilization was positively and significantly associated with continuous availability of essential medicines [ 17 , 48 ]. Moreover, limited medicines variety at lower-level health facilities cause patients to access higher levels [ 20 ].

Among the covariates, age of the household head, CHI membership status, wealth index, existence of chronic illness and perceived health status were significantly associated with the number of outpatient visits. Increased in the age of the household is associated with higher number of outpatient visits. This finding is consistent with the literature, which shows that older age, particularly being 65 or older, is associated with an increase in the number of outpatient visits [ 49 , 50 ], first choice of primary health care facilities [ 51 ], and health care utilization [ 52 , 53 ]. This could be because the occurrence of disease, particularly chronic illnesses, increases with age, resulting in a greater need for healthcare.

This study demonstrated that the number of outpatient visits of households who belong to the poor wealth class was higher than that of the rich class. This finding mirrors prior study which showed that higher and middle wealth class households were less likely to seek outpatient services from primary health centers compared to the lower class [ 54 ]. With respect to the choice of health facility, higher income is also inversely related to the use of primary health care facilities [ 20 , 51 ], as the better off families may have the demand to use better equipped and advanced health facilities. In contrary, it is documented that increased income is associated with higher probability of using health care, as it removes the financial barrier of access to care [ 52 , 55 , 56 ]. In the current study, the low number of outpatient visits in health centers among the rich class might not indicate low utilization of health care, rather it might be because of their preference to visit higher level or private health facilities. The poor might not have the financial means to seek care beyond the nearby health centers, which are relatively less costly. This is supported by the evidence that patients who can afford the cost of care often choose access at higher levels [ 20 ]. Similarly, an increase in hospital price cause patients to choose primary health care facilities for outpatient visits [ 57 ].

Households who were active members of CHI had a higher number of outpatient visits compared to those who quitted their membership. Findings of this study echo earlier evidence which showed that having an insurance plan is linked to an increased in health care utilization [ 37 , 48 , 53 , 58 , 59 , 60 ]. While removal of financial barriers to health care use is a possible explanation for the observed result, another is the presence of moral hazard behavior due to having health insurance. In the latter situation, people with insurance coverage tend to use more outpatient services because they know that the scheme will bear the medical bills [ 61 ]. Another plausible explanation is the gatekeeping effect of CHI membership. In the study area, CHI members have to follow the referral path in order to receive the scheme’s benefit packages. Member households are required to first visit the designated health centers and need to get referrals so as to receive health care at the next higher level health facility i.e. public hospitals [ 62 ]. As a result, their healthcare utilization is limited to the lower-level health facilities until they are referred to the higher level. In support of this view, a study revealed that patients with gatekeepers were more likely to choose community health centers first when seeking care, compared with patients having freedom of choice to seek medical care at any place [ 63 ].

The existence of chronic illness within the household was also linked to an increase in the number of outpatient visits. This is corroborated by the literature that having at least one chronic disease increased the number of outpatient visits [ 50 , 52 , 58 ], and promote first choice of PHC facilities [ 51 ]. This is because people with chronic illnesses have to visit health care facilities frequently for follow up cares that can be provided by PHC facilities.

The household head’s subjective assessment of the health status of the family has also an important bearing on the number of outpatient visits. Those who rated the health of the household as poor had higher number of outpatient visits compared to those who rate it as moderate and good. This is consistent with the existing evidence which showed that perceived poor health status is linked to more outpatient care utilization [ 49 , 50 , 52 , 56 ]. This may be true for people who perceive their health as poor to understand and value the need to seek healthcare, and to visit health facilities when the need arises.

The findings of this study will be an essential input for quality improvement endeavors as well as addressing challenges in efforts to attain universal health coverage. It provides a valuable lesson for Ethiopia and other low-income countries about the essence of enhancing the quality of care in order to leverage primary health care units while reducing the strain on higher-level health facilities. Despite the study gives an important lesson to healthcare managers and other relevant stakeholders, it is not without limitations. The study might be prone to recall bias in assessing the number of annual outpatient visits made by the household. Second, response bias is another possibility, as the head of the household might not have the full information on the use of outpatient services by all family members. Third, households that had not visited health centers for outpatient services in the 12 months period prior to the study were excluded to minimize recall bias. This non-utilization might be due to prior negative experience with the service providers. Fourth, the study fails to include some important covariates like the occurrence of acute illness in the last one year and its severity, which might confound the association between quality of care and outpatient visits. Finally, the study would not be immune to interviewer bias, despite efforts to minimize it by training data collectors on the purpose of the study, and how to use the data collection tool.

The current research showed that clients’ perception on the quality of care delivered at health centers is vital to attracting patients to the same facility for outpatient visits. Subscales of the perceived quality of care, particularly provider communication, information provision and access to care are strong predictors of the number of outpatient visits, showing the need to addressing issues related to quality of care. Unless patients are receiving a better quality of care, they might distrust and develop a negative attitude towards the health facility. Hence, strong efforts are required to improve the quality of care that rely on perception of clients with a special focus on improving communication skills of health care providers and removing facility level access barriers so as to boost clients’ interest to utilize primary health care facilities.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Akaike Information Criterion

Bayesian Information Criterion

Community Health Insurance

Deviance Information Criterion

Incidence Rate Ratio

Zero-Truncated Negative Binomial

Zero-Truncated Poisson

WHO. Primary health care on the road to universal health coverage: 2019 global monitoring report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

Google Scholar

WHO, The World Bank. Tracking universal health coverage: 2023 global monitoring report. Geneva: World Health Organization and The World Bank; 2023.

Kruk ME, Gage AD, Joseph NT, Danaei G, Garcia-Saiso S, Salomon JA. Mortality due to low-quality health systems in the universal health coverage era: a systematic analysis of amenable deaths in 137 countries. Lancet. 2018;392(10160):2203–12.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

OECD. Health at a glance 2023: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2023.

Book Google Scholar

WHO. Global reference list of 100 Core Health indicators (plus health-related SDGs). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

WHO. Monitoring the building blocks of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

WHO, OECD, and, WB. Delivering quality health services: a global imperative for universal health coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and The World Bank; 2018.

National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Crossing the global quality chasm: improving health care worldwide. Washington (DC): The National Academies; 2018.

Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, et al. High-quality health systems in the sustainable development goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet. 2018;6(11):e1196–252.

Ministry of Health. Health sector transformation plan 2021–2025. Addis Ababa: Ministry of Health of Ethiopia; 2021.

Hanefeld J, Powell-Jacksona T, Balabanovaa D. Understanding and measuring quality of care: dealing with complexity. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;2017(95):368–74.

Article Google Scholar

Larson E, Sharma J, Bohren MA, Tuncalp O. When the patient is the expert: measuring patient experience and satisfaction with care. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97(8):563–9.

Aljaberi MA, Juni MH, Al-Maqtari RA, Lye MS, Saeed MA, Al-Dubai SAR, Kadir Shahar H. Relationships among perceived quality of healthcare services, satisfaction and behavioural intentions of international students in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(9):e021180.

Aliman NK, Mohamad WN. Linking service quality, patients’ satisfaction and behavioral intentions: an investigation on private healthcare in Malaysia. Procedia - Social Behav Sci. 2016;224:141–8.

Agyapong A, Afi JD, Kwateng KO. Examining the effect of perceived service quality of health care delivery in Ghana on behavioural intentions of patients: the mediating role of customer satisfaction. Int J Healthc Manag. 2017;11(4):276–88.

Aysola J, Xu C, Huo H, Werner RM. The relationships between patient experience and quality and utilization of primary care services. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(6):1678–84.

Aggrey M, Appiah SCY. The influence of clients’ perceived quality on health care utilization. Int J Innov Appl Stud. 2014;9(2):918–24.

Akachi Y, Kruk ME. Quality of care: measuring a neglected driver of improved health. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(6):465–72.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Macinko J, Andrade FB, Souza Junior PRB, Lima-Costa MF. Primary care and healthcare utilization among older brazilians (ELSI-Brazil). Rev Saude Publica. 2018;52(2):6s.

PubMed Central Google Scholar

Liu Y, Kong Q, Yuan S, van de Klundert J. Factors influencing choice of health system access level in China: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0201887.

Lewis TP, Kassa M, Kapoor NR, Arsenault C, Bazua-Lobato R, Dayalu R, et al. User-reported quality of care: findings from the first round of the people’s voice survey in 14 countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2024;12(1):e112–22.

Utino L, Birhanu B, Getachew N, Ereso BM. Perceived quality of medical services at outpatient department of public hospitals in Dawro Zone, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):209.

Yin S, Hu M, Chen W. Quality perceptions and choice of public health facilities: a mediation effect analysis of outpatient experience in Rural China. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:2089–102.

Ethiopia Population Census Commission. Summary and statistical report of the 2007 population and housing census. Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission; 2008.

Hussien M, Azage M, Bayou NB. Continued adherence to community-based health insurance scheme in two districts of northeast Ethiopia: application of accelerated failure time shared frailty models. Int J Equity Health. 2022;21(1):16.

Bao Y, Fan G, Zou D, Wang T, Xue D. Patient experience with outpatient encounters at public hospitals in Shanghai: examining different aspects of physician services and implications of overcrowding. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(2).

Hu Y, Zhang Z, Xie J, Wang G. The outpatient experience questionnaire of comprehensive public hospital in China: development, validity and reliability. Int J Qual Health Care. 2017;29(1):40–6.

PubMed Google Scholar

Baltussen R, Ye Y. Quality of care of modern health services as perceived by users and non-users in Burkina Faso. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18(1):30–4.

Robyn PJ, Bärnighausen T, Souares A, Savadogo G, Bicaba B, Sié A, Sauerborn R. Does enrollment status in community-based insurance lead to poorer quality of care? Evidence from Burkina Faso. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:31.

Webster TR, Mantopoulos J, Jackson E, Heathercole-Lewis, Kidane L, Kebede5 S, et al. A brief questionnaire for assessing patient healthcare experiences in low-income settings. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23(3):258–68.

Benson T, Potts HW. A short generic patient experience questionnaire: howRwe development and validation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:499.

Kalmijn W. From discrete 1 to 10 towards continuous 0 to 10: the continuum approach to estimating the distribution of happiness in a nation. Soc Indic Res. 2013;110(2):549–57.

Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Q. 2005;83(4):1–28.

Hussien M, Azage M, Bayou NB. Perceived quality of care among households ever enrolled in a community-based health insurance scheme in two districts of northeast Ethiopia: a community-based, cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(10):e063098.

Cruyff MJ, van der Heijden PG. Point and interval estimation of the population size using a zero-truncated negative binomial regression model. Biom J. 2008;50(6):1035–50.

Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Regression analysis of count data. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013.

Alemayehu YK, Dessie E, Medhin G, Birhanu N, Hotchkiss DR, Teklu AM, Kiros M. The impact of community-based health insurance on health service utilization and financial risk protection in Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):67.

Aboaba KO, Akamo AA, Obalola TO, Bankole OA, Oladele AO, Yussuf OG. Factors influencing choice of healthcare facilities utilisation by rural households in Ogun State, Nigeria. Agricultura Trop et Subtropica. 2023;56(1):143–52.

Akin JS, Hutchinson P. Health-care facility choice and the phenomenon of bypassing. Health Policy Plan. 1999;14(2):135–51.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Croke K, Moshabela M, Kapoor NR, Doubova SV, Garcia-Elorrio E, HaileMariam D, et al. Primary health care in practice: usual source of care and health system performance across 14 countries. Lancet Glob Health. 2024;12(1):e134–44.

Arab M, Tabatabaei SG, Rashidian A, Forushani AR, Zarei E. The effect of service quality on patient loyalty: a study of private hospitals in Tehran, Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2012;41(9):71–7.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Idealistiana L, Ciptaningsih W. Relationship between patient’s perception of service quality and use of outpatient services. KnE Life Sciences. 2022.

Chichirez CM, Purcărea VL. Interpersonal communication in healthcare. J Med Life. 2018;11(2):119–22.

Larson E, Leslie HH, Kruk ME. The determinants and outcomes of good provider communication: a cross-sectional study in seven African countries. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e014888.

Kondasani RKR, Panda RK. Service quality perception and behavioural intention. J Health Manage. 2016;18(1):188–203.

Mehra P, Mishra A. Role of communication, influence, and satisfaction in patient recommendations of a physician. Vikalpa: J Decis Makers. 2021;46(2):99–111.

Sarkodie AO. The effect of the price of time on healthcare provider choice in Ghana. Humanit Social Sci Commun. 2022;9(1).

Kuwawenaruwa A, Wyss K, Wiedenmayer K, Metta E, Tediosi F. The effects of medicines availability and stock-outs on household’s utilization of healthcare services in Dodoma region, Tanzania. Health Policy Plan. 2020;35(3):323–33.

Kim KY, Lee E, Cho J. Factors affecting healthcare utilization among patients with single and multiple chronic diseases. Iran J Public Health. 2020;49(12):2367–75.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kong NY, Kim DH. Factors influencing health care use by health insurance subscribers and medical aid beneficiaries: a study based on data from the Korea welfare panel study database. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1133.

Liao R, Liu Y, Peng S, Feng XL. Factors affecting health care users’ first contact with primary health care facilities in north eastern China, 2008–2018. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(2).

Bitew Workie S, Mekonen N, Michael MW, Molla G, Abrha S, Zema Z, Tadesse T. Modern health service utilization and associated factors among adults in Southern Ethiopia. J Environ Public Health. 2021;2021:8835780.

Abera Abaerei A, Ncayiyana J, Levin J. Health-care utilization and associated factors in Gauteng Province, South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1305765.

Srivastava AK, Gupt RK, Bhargava R, Singh RR, Songara D. Utilisation of rural primary health centers for outpatient services - a study based on Rajasthan, India. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):387.

Gessesse A, Yitayal M, Kebede M, Amare G. Health service utilization among out-of-pocket payers and fee-wavier users in Saesie Tsaeda-Emba District, Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia: a comparative cross-sectional study. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:695–703.

Abu Bakar NS, Ab Hamid J, Mohd Nor Sham MSJ, Sham MN, Jailani AS. Count data models for outpatient health services utilisation. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022;22(1):261.

Ward TR. Implementing a gatekeeper system to strengthen primary care in Egypt: pilot study. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16(6):684–9.

Le DD, Gonzalez RL, Matola JU. Modeling count data for health care utilization: an empirical study of outpatient visits among Vietnamese older people. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2021;21(1):265.

Ly MS, Faye A, Ba MF. Impact of community-based health insurance on healthcare utilisation and out-of-pocket expenditures for the poor in Senegal. BMJ Open. 2022;12(12):e063035.

Eze P, Ilechukwu S, Lawani LO. Impact of community-based health insurance in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2023;18(6):e0287600.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Dong Y. How health insurance affects health care demand—a structural analysis of behavioral moral hazard and adverse selection. Econ Inq. 2012;51(2):1324–44.

Amhara Regional Health Bureau. Community-based health insurance implementation guideline, Revised edition. Bahir Dar: Amhara Regional Health Bureau; 2018.

Li W, Gan Y, Dong X, Zhou Y, Cao S, Kkandawire N, et al. Gatekeeping and the utilization of community health services in Shenzhen, China: a cross-sectional study. Med (Baltim). 2017;96(38):e7719.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The health offices of Kalu and Tehulederie districts, health extension workers, and kebele leaders are acknowledged for their cooperation during the data collection.

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Health Systems Management and Health Economics, School of Public Health, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

Mohammed Hussien

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

MH led the conceptualization and design of the study, data collection, data management, data analysis, and report writing. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mohammed Hussien .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Bahir Dar University’s College of Medicine and Health Science (protocol number 001/2021). Verbal informed consent was secured from each study participant. All methods in this study were carried out in accordance with relevant international and local guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Hussien, M. The role of perceived quality of care on outpatient visits to health centers in two rural districts of northeast Ethiopia: a community-based, cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 24 , 614 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11091-z

Download citation

Received : 26 December 2023

Accepted : 08 May 2024

Published : 10 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11091-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Quality of care

- Outpatient visits

- Health centers

BMC Health Services Research

ISSN: 1472-6963

- General enquiries: [email protected]

IMAGES

COMMENTS