What is a black hole event horizon (and what happens there)?

The interior secrets of black holes are guarded by a one-way light-trapping boundary called the event horizon.

- FAQs answered by an expert

- The discovery of the event horizon

Where is the event horizon and how big is it?

Imaging event horizons, additional resources.

The event horizon is the spherical outer boundary of a black hole loosely considered to be its "surface."

It is the point, according to NASA , that the gravitational influence of the black hole becomes so great that not even light is fast enough to escape it. As a result of the fact that Albert Einstein's theory of special relativity tells us that no signal can exceed the speed of light in a vacuum (c) humanity can never hope to obtain a signal from the one-way boundary that is an event horizon.

As such event horizons effectively act as cosmic gatekeepers preventing us from ever directly observing the secrets that lie at the heart of black holes. Yet they can reveal a great deal about the environment around them.

Related: What happens at the center of a black hole?

"The event horizon is the ultimate prison wall — one can get in but never get out," Avi Loeb, chair of astronomy at Harvard University, told Space.com.

When an item gets near an event horizon, a witness would see the item's image redden and dim as gravity distorted light coming from that item. At the event horizon, this image would effectively fade to invisibility.

Within the event horizon, one would find the black hole's singularity, where previous research suggests all of the object's mass has collapsed to an infinitely dense extent. This means the fabric of space and time around the singularity has also curved to an infinite degree, so the laws of physics as we currently know them break down.

"The event horizon protects us from the unknown physics near a singularity," Loeb said.

Event horizon and black Hole FAQs answered by an expert

Xavier Calmet is a professor of physics and astronomy in the School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences at the University of Sussex, U.K.

We asked Xavier Calmet, a professor of physics in the United Kingdom a few questions about black holes and event horizons.

What is a black hole event horizon?

It marks the boundary between the black hole and the rest of the universe.

What is special about this boundary?

Nothing inside the horizon can ever escape or come back across this boundary, not even light. This implies that nothing that enters the black hole horizon can be observed from outside this horizon.

Could we ever see past an event horizon?

It is a matter of viewpoint. From that of a distant observer, we never see anything fall into the black hole, i.e., enter the event horizon. The object approaching the event horizon would simply fade away over time and ultimately disappear. However, from the point of view of an observer falling into the black hole, he would not notice anything when crossing the horizon of an astrophysical black hole. Because the curvature at the horizon of astrophysical or large black holes is small, there are no strong tidal forces and the free-falling observer would simply enter the black hole without noticing that he passed the horizon.

What lies past the event horizon?

Empty space and nothing remarkable until one gets very close to the singularity at the center of the black hole. At that stage, tidal forces become extremely strong, and the observer would experience spaghettification — they would be stretched into a long pasta and would eventually be ripped apart by the strong gravitational forces.

Could anything ever escape the event horizon of a black hole?

This is a fascinating question and is linked to the infamous Hawking information paradox. In 2022, along with my colleague Stephen Hsu, we demonstrated in a series of papers how information can escape a black hole. We theorized that information is encoded in the quantum state of the gravitational field outside the black hole and imprinted in Hawking radiation and thus fully available to an outside observer. In that sense, information about what fell into a black hole can always be recovered.

Einstein, black holes, and event horizons: A tale of two singularities

The black hole and event horizon concepts were born from the 1915 theory of gravity conceived by Albert Einstein known as general relativity and solutions to the tensor equations that define it. A tenor is a mathematical equation that is similar to a vector but with four values rather than two. As a result, tensors are also sometimes called "four-vectors."

General relativity is also known as the "geometric theory of gravity" because it says that the presence of mass causes the very fabric of spacetime (the unification of space and time into a 4 dimension entity) to warp.

Think of this as being similar to placing balls of varying masses onto a stretched rubber sheet. The greater the mass of the ball, the more extreme the curvature, so a bowling ball warps the sheet far more than a marble. The same for celestial objects, a star creates more of a warp than a planet. Black holes are created when a massive star completely collapses as a result of its own gravity. The star's mass is compressed into an infinitely small space, causing an extreme warping of spacetime.

Because the term "black hole" refers to that entire warp, not just the infinite mass that dwells at its heart, ( Lambourne. R. J. A, 2010 , pg 171) it's more accurate to call black holes "spacetime events" rather than objects. And event horizons are the outer edge of these events where spacetime curves so much that anything that passes them is destined to make a one-way trip to the center of the black hole.

In 1915, less than a month after general relativity was first published astrophysicist Karl Schwarzschild became the first person to solve general relativity's field tensor equations, according to the Institute of Physics.

Schwarzschild studied general relativity while serving with the German army on the Eastern Front in the First World War in 191. He wrote to Einstein with his simple and exact solutions which Einstein feared might never be achieved as he himself had only managed approximate solutions. Schwarzschild passed away in 1916, the same year his solutions were published.

The mathematics of general relativity (Lambourne. R. J. A, 2010, pg 171) predicts two singularities. A coordinate singularity, which is the event horizon — the black hole's outer boundary, and a gravitational singularity, which represents the heart of the black hole.

Schwarzschild's solution gave the coordinate singularity and thus the event horizon a solid location around a black hole known as "Schwarzschild radius."

The coordinate singularity can be removed with a clever application of mathematics and transforming the coordinate system. But the gravitational singularity or "real singularity" can't be removed. It challenges physicists to this day, as it represents the point at which the physics that describes the universe completely breaks down.

The Schwarzschild radius (Rs) is a sphere located at the radius from the central "real" singularity of a black hole, which has a radius ( r) of r = 0, equal to radius equals 2 times Newton's gravitational constant or "big G" ( G) times the mass of the body (M) divided by the speed of light squared ( c²) [Lambourne. R. J. A, 2010, pg 172]. The equation for the Schwartzchild radius looks like this Rs = 2GM/c².

That equation implies that the size of the event horizon depends on the black hole's mass. The larger the mass the further out from the central singularity the event horizon will be.

It isn't just black holes that have a Schwarzschild radius all massive bodies like planets and stars do, but these aren't event horizons because these points are usually well within the bodies.

For example, given the sun's mass of 1.989 × 10³⁰ kg, its Schwarzschild radius occurs at about 1.86 miles (3 kilometers) from its central point, that's compared to the sun's radius of around 432,450 miles (696,000 kms). Earth's Schwarzschild radius is even closer to its central point, with our planet having a Schwarzschild radius of no more than 9 millimeters!

To see why the Schwartzchild radius constitutes a light-trapping surface consider that the escape velocity required to race away from the gravitational influence of a body is equal to the square root of 2 times the "big G" ( G) times the mass of the body (M) divided by the radius of the body — so Ves = (2GM/r)¹/². For Earth that gives a speed of around 7 miles per second (11.2 kms per second).

For a body with a radius less than 2GM/c² the escape velocity increases to more than 3.0 x 10⁸ meters per second, the speed of light in a vacuum tells us that not even light can outrace gravity at this point.

Another consequence of the Schwartzchild radius is that to become a black hole the radius of a body with mass must shrink to within Rs. If the sun were compressed enough to become a black hole its radius would have to shrink from over 400,000 miles to just 1.86 miles (3 kms). Meanwhile, for our planet to become a black hole the Earth's radius would have to shrink from around 4000 miles (6,400 kms) to just 0.35 inches (0.9 centimeters)!

Sagittarius A *, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way , is about 4.3 million times the mass of our sun and has a diameter of about 7.9 million miles (12.7 million km), while M87 at the heart of the Virgo A galaxy is about 6 billion solar masses and 11 billion miles (17.7 billion km) wide.

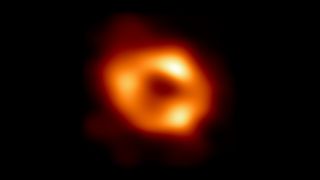

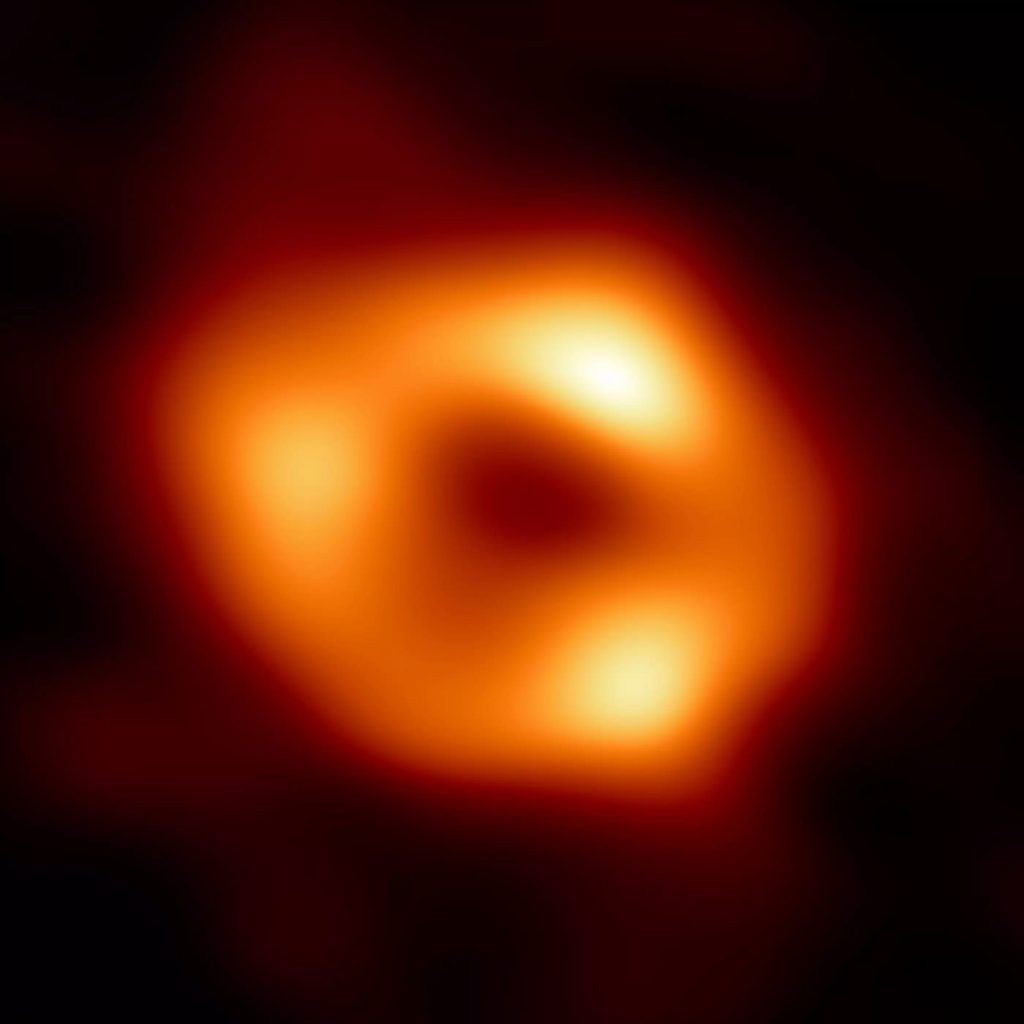

In 2019 the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) made history by capturing humanity's first direct image of a black hole, or as you'll realize by now more accurately, the environment immediately surrounding the black hole.

The image featured the supermassive black hole at the heart of Messier 87 (M87), located 53 million light-years away with a mass equivalent to around six and a half billion suns according to the EHT collaboration . The image shows a glowing ring of material traveling around the event horizon close to light speed.

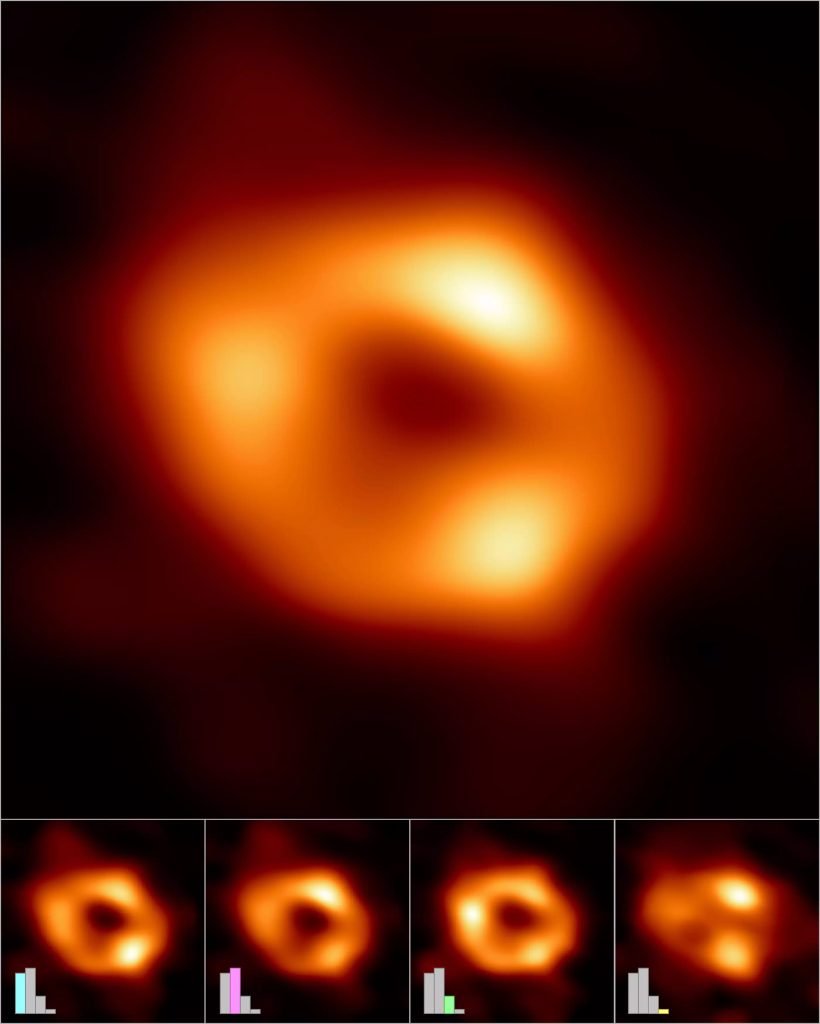

The array of telescopes across the globe that comprise the EHT and make an Earth-size virtual telescope made history again in 2022 when it imaged the supermassive black hole at the heart of our own galaxy, known as Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*).

"We were stunned by how well the size of the ring agreed with predictions from Einstein's Theory of General Relativity," EHT Project Scientist and Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics astronomer Geoffrey Bower said in a statement. "These unprecedented observations have greatly improved our understanding of what happens at the very center of our galaxy, and offer new insights on how these giant black holes interact with their surroundings."

Thus, the image of the black holes at the heart of M87 and the Milky Way demonstrates that while event horizons protect many secrets that lurk behind them, shielding the central singularity at the heart of these spacetime events from scrutiny, they also help reveal a wealth of information about their surroundings and the extreme physics that shape galaxies.

Astrophysicist Karl Schwarzschild is the man who first solved the field tensor equations of general relativity and for whom the location of the event horizon is named. You can read about this extraordinary life in this article published on the science communication website Secrets of the Universe. Read more about the Event Horizon Telescope and the capture of the first black hole image in 2019 with these resources from the Event Horizon Telescope . If you want to learn more about how massive stars die and collapse to form black holes check out these resources from NASA . The agency also explains how it studies these regions of space.

Bibliography

Lambourne. R. J. A., Relativity, Gravitation, and Cosmology, Cambridge University Press, [2010], ISBN: 978-0-521-13138-4 https://www.amazon.co.uk/Relativity-Gravitation-Cosmology-Robert-Lambourne/dp/0521131383

Ta-Pei Cheng, Relativity, Gravitation, and Cosmology: A basic introduction , Oxford University Press, [2010], ISBN 978-0-19-957364 Event Horizon, Swinburne Center for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, [accessed 02/18/23], [ https://astronomy.swin.edu.au/cosmos/e/Event+Horizon ]

Astronomers Reveal First Image of the Black Hole at the Heart of Our Galaxy, Event Horizon Telescope, [2022], [ https://eventhorizontelescope.org/blog/astronomers-reveal-first-image-black-hole-heart-our-galaxy ]

Astronomers Image Magnetic Fields at the Edge of M87's Black Hole, Event Horizon Telescope, [2021], [ https://eventhorizontelescope.org/blog/astronomers-image-magnetic-fields-edge-m87s-black-hole ] Astronomers Capture First Image of a Black Hole, Event Horizon Telescope, [2019], [ https://eventhorizontelescope.org/press-release-april-10-2019-astronomers-capture-first-image-black-hole ]

What Are Black Holes? NASA, [accessed 02/18/23], [ https://www.nasa.gov/vision/universe/starsgalaxies/black_hole_description.html ]

Eisenstaedt, D. Howard, J. Stachel (eds), The Early Interpretation of the Schwarzschild Solution, Einstein and the History of General Relativity: Einstein Studies, Vol. 1, pp. 213-234. Boston: Birkhauser, [1989]

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

- Charles Q. Choi Contributing Writer

Space pictures! See our space image of the day

'The last 12 months have broken records like never before': Earth exceeds 1.5 C warming every month for entire year

SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket can return to flight, FAA says

Most Popular

- 2 'Deadpool & Wolverine' has a sneaky Canadarm robot arm cameo at the end of time — but blink and you'll miss it

- 3 'Slingshot' is a surreal sci-fi head trip that questions its own reality (review)

- 4 Former U.S. Navy Seal Jonny Kim will be 1st Korean-American astronaut on ISS in March 2025

- 5 What were the Bell Riots in the greatest 'Star Trek: Deep Space Nine' time travel episode?

- The Magazine

- Stay Curious

- The Sciences

- Environment

- Planet Earth

What Are Wormholes, and Could They Be the Answer to Time Travel?

Wormholes, cosmic tunnels also known as einstein-rosen bridges, are a staple of science fiction. could they allow real-world humans to travel back in time.

The sci-fi landscape is littered with wormholes. From Douglas Adam's Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy and Rick and Morty to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, these theoretical constructs allow characters to zip between distant points in the universe as easy as stepping through a doorway.

An Einstein-Rosen bridge is the simplest kind of wormhole. And while it can, in theory, allow you to meet a new friend from a distant part of the universe, there are some important reasons why it won’t let you travel back in time.

Black Holes, White Holes and Wormholes

Let’s start with everybody’s favorite astronomical mystery: a black hole . Despite their fearsome reputation, they’re actually rather simple creature. They have a point of infinite density, known as the singularity, in their centers. They are surrounded by a boundary called the event horizon.

The event horizon doesn’t exist in the same way that the surface of a planet exists. Instead it’s just a mathematical line in the sand that tells you one thing: if you cross within that special distance, you’re trapped forever, because you’ll have to travel faster than the speed of light to escape.

Read More: 'Fuzzballs' Might Be the Answer to a Decades-Old Paradox About Black Holes

And that’s it. That’s a black hole. A singularity and an event horizon. All things that cross the event horizon will never escape back into the universe – things go in and never come out.

Mathematically we can also define the polar opposite of a black hole, which is conveniently called a white hole. White holes also have a singularity, but their event horizons act differently. Anything already on the outside of a white hole (like, the entire universe) can never, ever cross within it, no matter how hard it tries. And anything already inside the white hole will find itself ejected from it faster than the speed of light.

Now when we take a black hole and a white hole and connect their singularities together, we get an entirely new kind of object: an Einstein-Rosen bridge , better known as a wormhole.

Read More: Astronomers Found a Baffling Black Hole That Existed 13 Billion Years Ago

What Is a Wormhole?

Wormholes are essentially hollow tubes through space and time that can connect very distant regions of the universe. A star may be thousands of light-years away, but a wormhole can connect that star to us with a tunnel only a few steps long.

Wormholes also have the somewhat mystical ability to allow backwards time travel. If you take one end of the wormhole and accelerate it to a speed close to that of light, it will experience time dilation — its internal “clock” will run slower than the rest of the universe.

That will cause the two ends of the wormhole to no longer be synchronized in time. Then you could walk in one end and end up in your own past. Voilà: time travel.

Read More: Is There a Particle That Can Travel Back in Time?

Can Humans Travel Through Wormholes?

There's just one, tiny, teensy problem with this setup: Einstein-Rosen bridges are indeed wormholes, but the entrance to the wormhole sits behind the black hole event horizon. And the number one rule of black hole event horizons is that once you cross them, you’re never allowed to escape. Ever.

Once you pass through a black hole event horizon, you are forced towards the singularity, where you are guaranteed to meet your gruesome end. In other words, once you enter an Einstein-Rosen bridge, you will never escape.

So, the unfortunate truth with Einstein-Rosen bridges is that while they appear to be magical doorways to distant reaches of the universe, they are just as deadly as black holes. When you enter you can meet other travelers who have fallen in from the other side, and you could even carry on a conversation…briefly, before you both struck the singularity.

There have been attempts to stabilize Einstein-Rosen bridges and make them traversable by somehow getting their entrances to sit outside the event horizon. So far the only way we know how to do this is with exotic matter. If you threaded the wormhole tunnel with matter that had negative mass, then in principle you could have a not-deadly-at-all wormhole.

Alas, negative matter does not appear to exist in the universe, and so our wormhole — and time travel — dreams will have to remain as mere mathematical fantasies.

Read More: What Did Einstein's Theories Say About the Illusion of Time?

- space exploration

Already a subscriber?

Register or Log In

Keep reading for as low as $1.99!

Sign up for our weekly science updates.

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

- Special relativity

- General relativity

- Gravitational waves

- Black Holes & Co.

- Relativity and the Quantum

- Complete Spotlights

- The concept of EO

- About Albert Einstein

- Contributing Institutions

- Copyright policy

- Further reading

How the Event Horizon Telescope observes black holes

Researchers use the event horizon telescope to observe black holes at the centers of galaxies with high resolution., an article by anne-kathrin baczko, anton zensus and denise müller-dum.

Nobel laureates Reinhard Genzel (Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching, Germany) and Andrea Ghez (University of California in Los Angeles, USA) had already demonstrated through stellar motions that a black hole resides at the center of the Milky Way . Since May 2022, direct, visual proof of its existence has been available as well, as researchers revealed the first image of the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy.

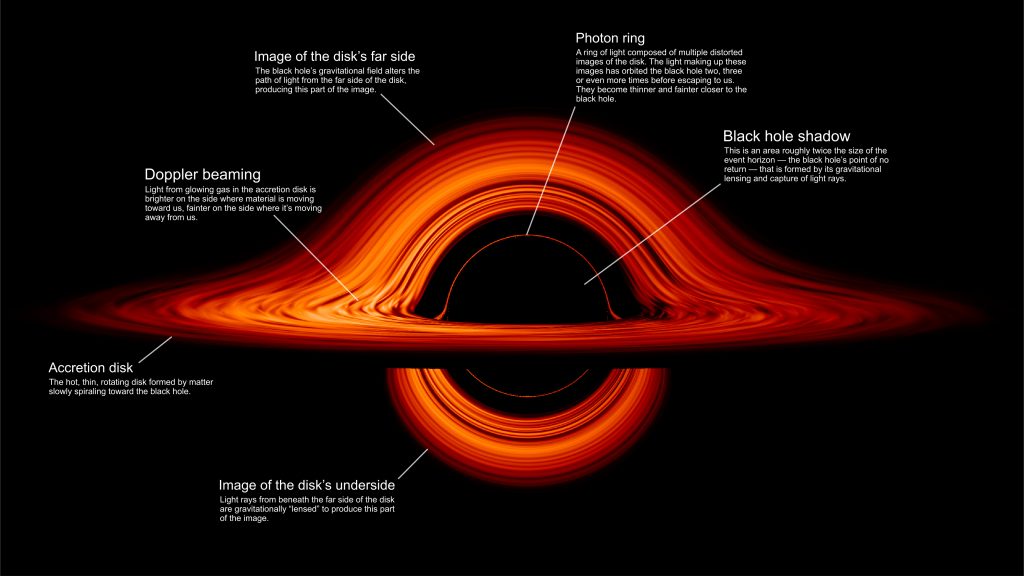

Image of an invisible object

The black hole cannot be imaged directly, because it does not emit light. However, the image shows glowing gas orbiting the black hole at high speed – the so-called accretion disk . This glowing gas emits radio waves that can be observed with ground-based telescopes. The dark region in the center is not, as one might think, the event horizon of the black hole, but its “shadow”: Light is deflected by the gravitational force of the black hole. The smallest possible distance at which it can travel around the black hole without falling in determines the extent of the dark central region in this image.

The Event Horizon Telescope

This image was enabled by Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) . With this technique, radio telescopes around the world are combined into a single virtual telescope – the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) . This was necessary, because there are two ways to achieve the highest possible resolution: short wavelength or large telescope size. With a wavelength of 1.3 millimeters, the EHT is already very close to the limit of what is technically possible. The physical size of the construction is also limited, since above a certain diameter it could no longer support its own weight. Thus, the only option to improve the resolution even further is to create a virtual telescope. This is achieved when several telescopes observe the same astronomical source at the same time. Radiation from the source reaches each telescope at slightly different times, which are precisely measured. A supercomputer combines the data streams from the individual telescopes, creating a virtual telescope – in the case of the EHT, one of the size of the Earth. The principle resembles that of optical interferometry, which is used at the VLTI, for example. The EHT thus allows, in principle, to detect an object the size of a ping-pong ball on the Moon.

In 2017, when the image of Sagittarius A* was taken, the following observatories were part of the EHT:

- Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile.

- Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX) in Chile

- IRAM 30-m telescope in Pico Veleta, Spain

- James Clark Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) at Maunakea, Hawaii, USA

- Large Millimeter Telescope (LMT) Alfonso Serrano in Mexico

- South Pole Telescope (SPT)

- Submillimeter Array (SMA) on Maunakea, Hawaii, USA

- Submillimeter Telescope (SMT) on Mount Graham in Arizona, USA

Other telescopes have been added since then (as of July 2022):

- 12-m telescope at the University of Arizona on Kitt Peak, AZ, USA.

- Greenland Telescope

- IRAM-NOEMA telescope in the French Alps

With this telescope network, researchers study active galaxies and the surroundings of black holes at large distances. During the first measurement campaign of the EHT in April 2017, researchers targeted several galaxies , including Virgo A at 53 million light-years from Earth.

From observation to image

Powerful highly-specialized supercomputers – so-called correlators – combine the data from the individual telescopes into a common data set. One of these correlators is located at the Max Planck Institute for Radioastronomy in Bonn. There, about half of the data from the 2017 measurement campaign was correlated. In 2019, the researchers were able to generate an image of M87* at the center of the Virgo A galaxy. This image made headlines in 2019 – it was the first ever direct image of a black hole.

Sagittarius A* was observed for several nights in April 2017 as well. However, data analysis took longer – even though the center of our galaxy is only 27,000 light-years away and thus much closer than M87*. A reason for this was ultimately the difference in size of the two black holes. While the hot gas, which is moving almost at the speed of light, needed several days to weeks to orbit M87*, it took only minutes for the much smaller Sagittarius A*. Thus, the appearance of Sagittarius A* changed very quickly during the observations. However, the precision of the VLBI technique, and ultimately the sensitivity and resolution of the virtual telescope, rely on the relative uniformity of the source’s appearance over a long period of time. In addition, the Earth lies in the galactic plane of the Milky Way, which causes scattering. The researchers thus had to develop new methods to eliminate these and other interfering effects.

In May 2022, the researchers of the EHT collaboration finally released the first image of the black hole in the center of the Milky Way. It represents an average of thousands of images reconstructed from the same correlated data by different scientists using different methods. The ring-shaped structure is strikingly similar to that of M87*, but – as predicted – it is more than a thousand times smaller, corresponding to its lower mass.

Testing theories

Sagittarius A* had already been thoroughly investigated before it was observed with the EHT. For example, its mass of 4.3 million solar masses and its distance from Earth, which is 27,000 light-years, were known precisely owing to the work of, among others, Nobel laureates Reinhard Genzel and Andrea Ghez. This allowed the researchers to predict the size of the shadow and compare it with the measurements. The result: the measured dimensions agree very well with the predictions of general relativity.

The images will also allow to compare the two black holes Sagittarius A* and M87*. In addition, the data can be used to test how well current theories describe the behavior of gravity and matter in the vicinity of supermassive black holes.

In the meantime, the measurements are being continued: With now eleven observatories, the Event Horizon telescope observed the night sky during a campaign in March 2022.

Further Information

Press release of the Max Planck Institute for Radioastronomy on the image of Sagittarius A*

Press release of the Max Planck Society on the image of Sagittarius A*

is an astrophysicist at the Max Planck Institute for Radioastronomy in Bonn, Germany.

is director of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn and head of the research department “Radio Astronomy/VLBI”.

is a trained physicist and geoscientist and works as a science communicator in Bremen, Germany.

Cite this article as: Anne-Kathrin Baczko, Anton Zensus and Denise Müller-Dum, “How the Event Horizon Telescope observes black holes” in: Einstein Online Band 14 (2022), 1003

Further Articles

What is Einstein Online?

Einstein Online is a web portal with comprehensible information on Einstein's theories of relativity and their most exciting applications from the smallest particles to cosmology.

Einstein Online is provided by the

Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics (Albert-Einstein-Institut)

About Einstein Online

Includes information on our authors and contributing Institutions , and a brief history of the website.

More than 400 entries from "absolute zero" to "XMM Newton" - whenever you see this type of link on an Einstein Online page, it'll take you to an entry in our relativistic dictionary.

a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z

Links & Literatur

Our recommendations for books and websites on relativity and its history.

Legal notice | Privacy policy

New NASA Black Hole Visualization Takes Viewers Beyond the Brink

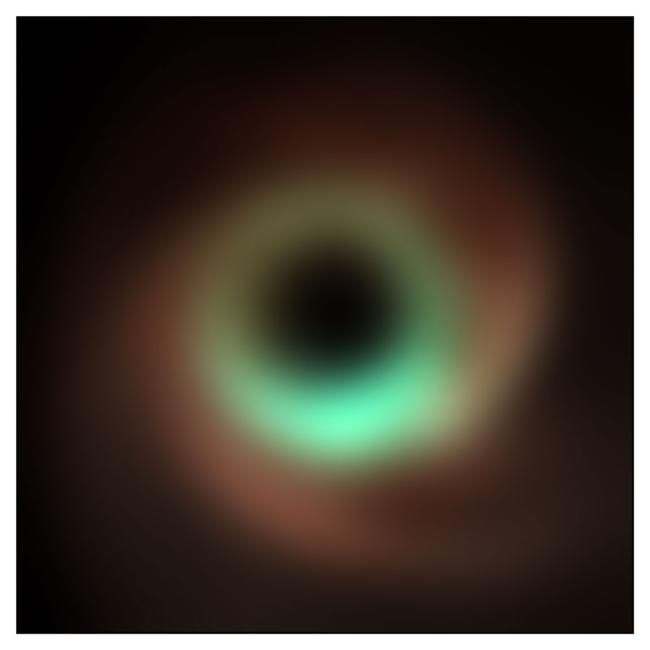

Ever wonder what happens when you fall into a black hole? Now, thanks to a new, immersive visualization produced on a NASA supercomputer, viewers can plunge into the event horizon, a black hole’s point of no return.

“People often ask about this, and simulating these difficult-to-imagine processes helps me connect the mathematics of relativity to actual consequences in the real universe,” said Jeremy Schnittman, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, who created the visualizations. “So I simulated two different scenarios, one where a camera — a stand-in for a daring astronaut — just misses the event horizon and slingshots back out, and one where it crosses the boundary, sealing its fate.”

The visualizations are available in multiple forms. Explainer videos act as sightseeing guides, illuminating the bizarre effects of Einstein’s general theory of relativity. Versions rendered as 360-degree videos let viewers look all around during the trip, while others play as flat all-sky maps.

To create the visualizations, Schnittman teamed up with fellow Goddard scientist Brian Powell and used the Discover supercomputer at the NASA Center for Climate Simulation . The project generated about 10 terabytes of data — equivalent to roughly half of the estimated text content in the Library of Congress — and took about 5 days running on just 0.3% of Discover’s 129,000 processors. The same feat would take more than a decade on a typical laptop.

The destination is a supermassive black hole with 4.3 million times the mass of our Sun, equivalent to the monster located at the center of our Milky Way galaxy.

“If you have the choice, you want to fall into a supermassive black hole,” Schnittman explained. “Stellar-mass black holes, which contain up to about 30 solar masses, possess much smaller event horizons and stronger tidal forces, which can rip apart approaching objects before they get to the horizon.”

This occurs because the gravitational pull on the end of an object nearer the black hole is much stronger than that on the other end. Infalling objects stretch out like noodles, a process astrophysicists call spaghettification .

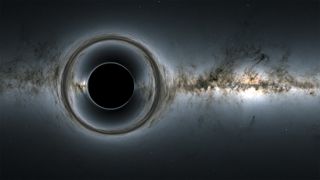

The simulated black hole’s event horizon spans about 16 million miles (25 million kilometers), or about 17% of the distance from Earth to the Sun. A flat, swirling cloud of hot, glowing gas called an accretion disk surrounds it and serves as a visual reference during the fall. So do glowing structures called photon rings, which form closer to the black hole from light that has orbited it one or more times. A backdrop of the starry sky as seen from Earth completes the scene.

As the camera approaches the black hole, reaching speeds ever closer to that of light itself, the glow from the accretion disk and background stars becomes amplified in much the same way as the sound of an oncoming racecar rises in pitch. Their light appears brighter and whiter when looking into the direction of travel.

The movies begin with the camera located nearly 400 million miles (640 million kilometers) away, with the black hole quickly filling the view. Along the way, the black hole’s disk, photon rings, and the night sky become increasingly distorted — and even form multiple images as their light traverses the increasingly warped space-time.

In real time, the camera takes about 3 hours to fall to the event horizon, executing almost two complete 30-minute orbits along the way. But to anyone observing from afar, it would never quite get there. As space-time becomes ever more distorted closer to the horizon, the image of the camera would slow and then seem to freeze just shy of it. This is why astronomers originally referred to black holes as “frozen stars.”

At the event horizon, even space-time itself flows inward at the speed of light, the cosmic speed limit. Once inside it, both the camera and the space-time in which it's moving rush toward the black hole's center — a one-dimensional point called a singularity , where the laws of physics as we know them cease to operate.

“Once the camera crosses the horizon, its destruction by spaghettification is just 12.8 seconds away,” Schnittman said. From there, it’s only 79,500 miles (128,000 kilometers) to the singularity. This final leg of the voyage is over in the blink of an eye.

In the alternative scenario, the camera orbits close to the event horizon but it never crosses over and escapes to safety. If an astronaut flew a spacecraft on this 6-hour round trip while her colleagues on a mothership remained far from the black hole, she’d return 36 minutes younger than her colleagues. That’s because time passes more slowly near a strong gravitational source and when moving near the speed of light.

“This situation can be even more extreme,” Schnittman noted. “If the black hole were rapidly rotating, like the one shown in the 2014 movie ‘Interstellar,’ she would return many years younger than her shipmates.”

By Francis Reddy NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center , Greenbelt, Md. Media Contact: Claire Andreoli 301-286-1940 [email protected] NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Related Terms

- Astrophysics

- Black Holes

- Galaxies, Stars, & Black Holes

- Galaxies, Stars, & Black Holes Research

- Goddard Space Flight Center

- Supermassive Black Holes

- The Universe

Explore More

NASA, ESA Missions Help Scientists Uncover How Solar Wind Gets Energy

Hubble Zooms into the Rosy Tendrils of Andromeda

Aaron Vigil Helps Give SASS to Roman Space Telescope

The stars in the big Wyoming skies inspired Aaron Vigil as a child to dream big. Today, he’s a mechanical engineer working on the Solar Array Sun Shield (SASS) for the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope at Goddard. Name: Aaron VigilTitle: Mechanical EngineerFormal Job Classification: Aerospace Technology, Flight StructuresOrganization: Mechanical Engineering, Engineering and Technology Directorate (Code […]

Event Horizon Telescope Makes Highest-Resolution Black Hole Detections from Earth

- News Release

- What do black holes look like?

- Black Holes

- Radio and Geoastronomy

- Event Horizon Telescope (EHT)

- The Submillimeter Array - Maunakea, HI

- The Greenland Telescope

- Sheperd Doeleman

Using the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), astronomers have achieved very-long-baseline interferometry test observations at 345 GHz, the highest-resolution such observations ever obtained from the surface of Earth. Scientists estimate that the breakthrough will result in a remarkable 50% increase in detail, sharpening images and observations of black holes and their surrounding regions.

The Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) Collaboration has conducted test observations achieving the highest resolution ever obtained from the surface of the Earth, by detecting light from the centers of distant galaxies at a frequency of around 345 GHz.

When combined with existing images of supermassive black holes at the hearts of M87 and Sgr A at the lower frequency of 230 GHz, these new results will not only make black hole photographs 50% crisper but also produce multi-color views of the region immediately outside the boundary of these cosmic beasts.

The new detections, led by scientists from the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian (CfA) that includes the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO), were published today in The Astronomical Journal .

"With the EHT, we saw the first images of black holes by detecting radio waves at 230 GHz, but the bright ring we saw, formed by light bending in the black hole’s gravity still looked blurry because we were at the absolute limits of how sharp we could make the images," said paper co-lead Alexander Raymond, previously a postdoctoral scholar at the CfA, and now at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (NASA-JPL). "At 345 GHz, our images will be sharper and more detailed, which in turn will likely reveal new properties, both those that were previously predicted and maybe some that weren't."

The EHT creates a virtual Earth-sized telescope by linking together multiple radio dishes across the globe, using a technique called very-long-baseline interferometry (VLBI). To get higher-resolution images, astronomers have two options: increase the distance between radio dishes or observe at a higher frequency. Since the EHT was already the size of our planet, increasing the resolution of ground-based observations required expanding its frequency range, and that's what the EHT Collaboration has now done.

"To understand why this is a breakthrough, consider the burst of extra detail you get when going from black and white photos to color," said paper co-lead Sheperd "Shep" Doeleman, an astrophysicist at the CfA and SAO, and Founding Director of the EHT. "This new 'color vision' allows us to tease apart the effects of Einstein’s gravity from the hot gas and magnetic fields that feed the black holes and launch powerful jets that stream over galactic distances."

A prism splits white light into a rainbow of colors because different wavelengths of light travel at different speeds through glass. But gravity bends all light similarly, so Einstein predicts that the size of the rings seen by the EHT should be similar at both 230 GHz and 345 GHz, while the hot gas swirling around the black holes will look different at these two frequencies.

This is the first time the VLBI technique has been successfully used at a frequency of 345 GHz. While the ability to observe the night sky with single telescopes at 345 GHz existed before, using the VLBI technique at this frequency has long presented challenges that took time and technological advances to overcome. Water vapor in the atmosphere absorbs waves at 345 GHz much more than at 230 GHz weakening the signals from black holes at the higher frequency. The key was to improve the sensitivity of the EHT, which the researchers did by increasing the bandwidth of the instrumentation and waiting for good weather at all sites.

The new experiment used two small subarrays of the EHT—made up of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and the Atacama Pathfinder EXperiment (APEX) in Chile, the IRAM 30-meter telescope in Spain, the NOrthern Extended Millimeter Array (NOEMA) in France, the Submillimeter Array (SMA) on Maunakea in Hawai'i, and the Greenland Telescope —to make measurements with resolution as fine as 19 microarcseconds.

"The most powerful observing locations on Earth exist at high altitudes, where atmospheric transparency and stability is optimal but weather can be more dramatic," said Nimesh Patel, an astrophysicist at the CfA and SAO, and a project engineer at SMA, adding that at the SMA, the new observations required braving icy roads at Maunakea to open the array in the stable weather after a snow storm with minutes to spare. "Now, with high-bandwidth systems that process and capture wider swaths of the radio spectrum, we are starting to overcome basic problems in sensitivity, like weather. The time is right, as the new detections prove, to advance to 345 GHz."

This achievement also provides another stepping stone on the path to creating high-fidelity movies of the event horizon environment surrounding black holes, which will rely on upgrades to the existing global array. The planned next-generation EHT (ngEHT) project will add new antennas to the EHT in optimized geographical locations and enhance existing stations by upgrading them all to work at multiple frequencies between 100 GHz and 345 GHz at the same time. As a result of these and other upgrades, the global array is expected to increase the amount of sharp, clear data EHT has for imaging by a factor of 10, enabling scientists to not only produce more detailed and sensitive images but also movies starring these violent cosmic beasts.

"The EHT's successful observation at 345 GHz is a major scientific milestone," said Lisa Kewley, Director of CfA and SAO. "By pushing the limits of resolution, we're achieving the unprecedented clarity in the imaging of black holes we promised early on, and setting new and higher standards for the capability of ground-based astrophysical research."

"First Very Long Baseline Interferometry Detections at 870 μm," A.W. Raymond, S. Doeleman, et al (2024), The Astronomical Journal , DOI: 10.3847/1538-3881/ad5bdb .

About the Submillimeter Array (SMA)

The Submillimeter Array is a joint project of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory and the Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics. We acknowledge the significance that Maunakea, where the SMA is located, has for the indigenous Hawaiian people.

About the Greenland Telescope

The Greenland Telescope is a joint project of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory and the Academica Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics.

The EHT Collaboration involves more than 400 researchers from Africa, Asia, Europe, North and South America, with around 270 participating in this paper. The international collaboration aims to capture the most detailed black hole images ever obtained by creating a virtual Earth-sized telescope. Supported by considerable international efforts, the EHT links existing telescopes using novel techniques—creating a fundamentally new instrument with the highest angular resolving power that has yet been achieved.

The EHT consortium consists of 13 stakeholder institutes; the Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, the University of Arizona, the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian including the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, the University of Chicago, the East Asian Observatory, Goethe University Frankfurt, Institut de Radioastronomie Millimétrique, Large Millimeter Telescope, Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, MIT Haystack Observatory, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, and Radboud University.

About the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian

The Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian is a collaboration between Harvard and the Smithsonian designed to ask—and ultimately answer—humanity's greatest unresolved questions about the nature of the universe. The Center for Astrophysics is headquartered in Cambridge, MA, with research facilities across the U.S. and around the world.

Media Contact

Amy Oliver Public Affairs Officer, Whipple Observatory Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian +1-520-879-4406 [email protected]

Related News

Cfa celebrates 25 years with the chandra x-ray observatory, cfa astronomers help find most distant galaxy using james webb space telescope, astronomers unveil strong magnetic fields spiraling at the edge of milky way’s central black hole, black hole fashions stellar beads on a string, m87* one year later: proof of a persistent black hole shadow, unexpectedly massive black holes dominate small galaxies in the distant universe, unveiling black hole spins using polarized radio glasses, a supermassive black hole’s strong magnetic fields are revealed in a new light, nasa telescopes discover record-breaking black hole, new horizons in physics breakthrough prize awarded to cfa astrophysicist, dasch (digital access to a sky century @ harvard), sensing the dynamic universe, champ (chandra multiwavelength project) and champlane (chandra multiwavelength plane) survey.

Screen Rant

Event horizon is a warhammer 40k prequel: fan theory explained.

Your changes have been saved

Email is sent

Email has already been sent

Please verify your email address.

You’ve reached your account maximum for followed topics.

Tom Cruise's Aerial Fight In Top Gun: Maverick Ending Underwhelms Real Fight Pilot

"does what no other trilogy has ever been able to do": quentin tarantino reveals his pick for the best movie trilogy, stephen king-defended 2024 horror movie becomes streaming success.

Some fans believe that cult classic Event Horizon is a Warhammer 40k prequel, but is there anything to back that up? After directing Mortal Kombat , director Paul W.S. Anderson turned down other high-profile gigs like Alien: Resurrection to focus on Event Horizon instead. This followed a rescue crew who recover an experimental spaceship that vanished years before, and find it has - quite literally - been to Hell and back. The movie was put together under a tight production schedule and was both a critical and commercial failure upon release in 1997.

Event Horizon was quickly rediscovered on VHS and DVD, with the film's haunting visuals, beautiful production design and terrifying scenes - such as the infamous "blood orgy" video - ensuring it found a loving audience. It's also well-known that Anderson had to trim even more graphic footage from the movie following test screenings, which reportedly even saw an audience member faint. Sadly, it appears this deleted footage has been lost to time, and an uncut version of Event Horizon is unlikely to emerge.

Related: Why Event Horizon Is Underrated (& Why It Bombed At The Box Office)

The Event Horizon spaceship itself is powered by a gravity drive that can fold spacetime, making it possible to travel from one side of the universe to another. Sadly for the original crew, they ended up in a hellish alternate dimension where they mutilate and murder one another. This dimension is never shown in Event Horizon - which also has some Hellraiser similarities - but the description of this "chaos" filled void has led to a convincing fan theory the film is a secret Warhammer 40k prequel.

Event Horizon's Crew May Have Visited 40k's "Chaos" Dimension

Warhammer 40k is a tabletop wargame set in the distant future where humanity is in constant battle with various alien and supernatural factions. The extensive lore of the universe makes it near impossible to explain concisely, but in relation to Event Horizon , it appears the crew of the ship may have entered into "The Warp," also known as "The Immaterium." This is an alternate dimension made up of psychic energy and is also home to the so-called Chaos Gods and other daemonic beings. Ships can travel through the Warp, but to protect themselves from the dark forces found there, they need to engage a Gellar Field to keep the crews safe from the madness outside.

The Event Horizon / Warhammer 40k prequel theory posits that the Event Horizon's - which has a cool Sam Neill easter egg - crew marked humanity's first time traveling through the Immaterium, and its gravity drive later led to the creation of 40k's Warp-Drive. The crew was exposed to the chaotic energy of this dimension, which drove them to acts of violence and murder, and when the Event Horizon returned it brought an entity - possibly a Daemon of Chaos - back with it that attacks the rescue crew, causing hallucinations that prey on their fears.

Neill's Dr. Weir later becomes possessed by the evil presence on the ship, ripping out his eyes and describing the alternate dimension as one of " pure chaos ." From the movie's gothic design to the many similarities between the two properties, the theory linking Event Horizon - which is getting a TV series - and Warhammer 40k together is a persuasive one. The pieces line up nicely and if nothing else, it's a fun theory to explore. Event Horizon screenwriter Philip Eisner also answered a fan query about Warhammer 40k on Twitter in 2017, and stated " I played the s*** out of 40K, so it was definitely an influence, conscious or otherwise ."

Next: Event Horizon's Two Alternate Endings Explained (& Why They Weren't Used)

- SR Originals

Cookie banner

We use cookies and other tracking technologies to improve your browsing experience on our site, show personalized content and targeted ads, analyze site traffic, and understand where our audiences come from. To learn more or opt-out, read our Cookie Policy . Please also read our Privacy Notice and Terms of Use , which became effective December 20, 2019.

By choosing I Accept , you consent to our use of cookies and other tracking technologies.

Follow The Ringer online:

- Follow The Ringer on Twitter

- Follow The Ringer on Instagram

- Follow The Ringer on Youtube

Site search

- Fantasy Football Rankings

- Bill Simmons Podcast

- 24 Question Party People

- 60 Songs That Explain the ’90s

- Against All Odds

- Bachelor Party

- The Bakari Sellers Podcast

- Beyond the Arc

- The Big Picture

- Black Girl Songbook

- Book of Basketball 2.0

- Boom/Bust: HQ Trivia

- Counter Pressed

- The Dave Chang Show

- East Coast Bias

- Every Single Album: Taylor Swift

- Extra Point Taken

- Fairway Rollin’

- Fantasy Football Show

- The Fozcast

- The Full Go

- Gambling Show

- Gene and Roger

- Higher Learning

- The Hottest Take

- Jam Session

- Just Like Us

- Larry Wilmore: Black on the Air

- Last Song Standing

- The Local Angle

- Masked Man Show

- The Mismatch

- Mint Edition

- Morally Corrupt Bravo Show

- New York, New York

- Off the Pike

- One Shining Podcast

- Philly Special

- Plain English

- The Pod Has Spoken

- The Press Box

- The Prestige TV Podcast

- Recipe Club

- The Rewatchables

- Ringer Dish

- The Ringer-Verse

- The Ripple Effect

- The Rugby Pod

- The Ryen Russillo Podcast

- Sports Cards Nonsense

- Slow News Day

- Speidi’s 16th Minute

- Somebody’s Gotta Win

- Sports Card Nonsense

- This Blew Up

- Trial by Content

- Ringer Wrestling Worldwide

- What If? The Len Bias Story

- Wrighty’s House

- Wrestling Show

- Latest Episodes

- All Podcasts

Filed under:

- Pop Culture

“Hell Is Only a Word”: The Enduring Terror of ‘Event Horizon’

Paul W.S. Anderson’s space-horror film was maligned during its 1997 release, but has since gained a cult following and will be adapted into a TV series for Amazon. But the biggest question surrounding ‘Event Horizon’ still persists: Will we ever get a diabolical director’s cut?

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: “Hell Is Only a Word”: The Enduring Terror of ‘Event Horizon’

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/67191681/event_horizon_FEATURE.0.jpg)

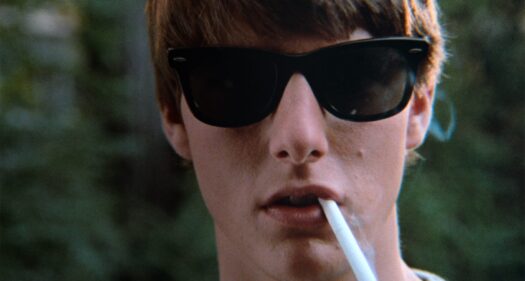

For films that feature a character descending into madness, it’s all about the look. Jack Torrance, staring out into the endless blizzard outside the Overlook Hotel; Travis Bickle, shaving his head into a Mohawk; Colonel Kurtz, moving out of the shadows of his decaying temple. Sometimes, a striking image tells you everything you need to know. For Sam Neill’s character in a criminally overlooked horror film from 1997, it’s the sight of him sitting in the captain’s chair of a doomed spaceship, having torn out his own eyes.

“Where we’re going,” he says, “we won’t need eyes to see.”

Welcome to Event Horizon , the batshit masterpiece from filmmaker Paul W.S. Anderson—and a more literal interpretation of what it means to go to hell and back. The year is 2047, and Earth has received a distress signal near Neptune from the Event Horizon , a scientific research vessel that mysteriously vanished without a trace seven years prior. The movie centers on a rescue team—led by Laurence Fishburne’s Captain Miller—that is tasked with traveling to the far reaches of our solar system to find out what happened to the ship, and with any luck, rescue some survivors. Joining Miller’s crew is Dr. Weir, played by Neill, the architect of the Event Horizon , who reveals the true nature of the ship: It was designed so that mankind could travel faster than the speed of light by opening a rift in the space-time continuum.

But it turns out the setup had some, uh, drawbacks—namely, that the Event Horizon inadvertently opened a portal to what’s essentially a hell dimension. (It should come as no surprise that the members of the original crew are in no condition to be rescued.) And by returning to the ship and restoring its power, Dr. Weir, Captain Miller, and his crew are subjecting themselves to the same horrors: a malignant presence that preys on the characters’ worst fears and traumas. Think The Shining , but in outer space, with a little Hellraiser thrown in for good measure.

Any movie centered on a crew being terrorized in space will inevitably draw comparisons to Alien , but as Anderson tells me in a phone interview, he was committed to executing his own vision with Event Horizon . “I wanted to do something different that hadn’t been done in spaceships before, and because we were telling a gothic horror story, I reached back in time,” he says. What particularly inspired the director, after a trip to Paris, was the Gothic architecture of the Notre Dame Cathedral. “Using an architectural cam program, we basically built Notre Dame Cathedral in the computer, and then we pulled it apart and we used different elements of it to build the Event Horizon ,” Anderson explains. “So, the towers from Notre Dame became the engine thruster pods.”

While Ridley Scott was able to lean on H.R. Giger’s memorable creature designs to make the Alien universe and its deadly xenomorphs so iconic, Anderson turned to painters like Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel for further inspiration. “ Event Horizon was really an opportunity for me to do something visually that was a blank canvas,” he says. “That was the kind of freedom that I wouldn’t have had if I’d been working on a universe that was already established.” The result was some of the most aesthetically striking and unsettling sci-fi production design this side of Scott’s masterwork. The Event Horizon itself has an ominous, cavernous quality to it; like the Overlook Hotel, the ship is very much its own sinister character.

For the production of the film, Paramount Pictures—to borrow a line from a more familiar Sam Neill movie from the ’90s —spared no expense. Event Horizon had a $60 million budget, and while some elements of a film set in outer space required special effects, much of the ship itself was actually built. “I heard from all of the actors individually at one point or another that they found the sets had a disturbing vibe to them,” Anderson says. “That’s how I knew we were doing something right when people would go, ‘I love working with you Paul, but I hate coming to work. It was just horrible. The feeling on set is just … ’ and it was actually the sets themselves, because the crew couldn’t have been nicer. But there was a disturbing vibe. I really felt like we created a very physical haunted house for the actors to interact with.”

Contrary to the ill-fated premise, the Event Horizon production was smooth sailing—in fact, the film didn’t encounter any serious problems until another doomed ship got in its way. James Cameron’s Titanic was originally set to be released in the summer of 1997, but needed to be pushed back. The film, cofinanced with 20th Century Fox, was going over budget and shaping up to be a pricey shitshow. Titanic and Cameron would go on to have a happy ending—i.e., it became the highest-grossing movie of all time to that point; Cameron got to shout “I’m the king of the world!” at the Oscars —but in the interim, Paramount needed something else to fill its summer slot. Enter Event Horizon .

That arrangement was easier said than done. For Anderson, postproduction on the film became a real time crunch. Instead of getting 10 weeks to cut the movie into shape, he had to make do with four, working around the clock. And along with editing the film and finishing the effects, Event Horizon had to be screen-tested for audiences and Paramount executives within this compressed period—and the first test didn’t go well. “I think we never fully recovered in the postproduction process from that initial bad test,” Anderson says.

The finished version of the film runs at around 90 minutes without credits; there was a lot of material that was left on the cutting-room floor. Included in the scraps was a grisly homage to 2001: A Space Odyssey ’s famous match cut in which, instead of a spinning bone transitioning to a satellite in orbit, Captain Miller finds a floating tooth in zero gravity with some gum still attached to the end of it. One moment that did make the final cut—Kathleen Quinlan’s medical technician Peters being tormented by a hallucination of her son, who’s back on Earth, with his legs covered in bloody lesions—was originally even more gruesome, as Anderson had the boy’s legs enveloped by real maggots. “Interestingly, when you put it in front of an audience, it was too much,” he says. “They were horrified by seeing the child and seeing the legs, but then when you showed the maggots, people disengaged. They went, ‘Oh my god,’ they would turn away from the screen. And you realize that as a filmmaker, you’d broken the suspension of disbelief.”

Anderson is the first to admit Event Horizon has some pacing issues, and that the film could’ve included a bit more backstory for Dr. Weir, whose descent into madness aboard the ship is caused by visions of his dead wife. (The ship is basically using Dr. Weir’s wife to beckon him to hell.) “I think when we trimmed it, we made some good decisions but we made some bad decisions as well,” Anderson says. “And again, I say that in the context of the finished movie—a movie that I absolutely love.”

The initial response to Event Horizon , however, was far from welcoming. “The screenplay creates a sense of foreboding and afterboding, but no actual boding,” wrote the late Roger Ebert , who gave the film two stars. For the Chicago Reader , Jonathan Rosenbaum was even more unforgiving: “My idea of hell would be having to see this stinker again.” All told, Event Horizon has a 27 percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes—if Metacritic is more your thing, its Metascore of 35 isn’t much better—and was a box office bomb, grossing less than half of its production budget . Anderson believes the harsh reception was, at least in part, a result of Paramount’s failure to effectively market the film to audiences. “They almost sold it as a slightly darker version of Star Trek or something: ‘From the studio who brought you Star Trek , here’s another space thing,’” he says. “One of the heads of Paramount called me a little while afterward and said, ‘We should have done much better with that movie when we first released it.’”

But for films misunderstood, critically panned, or just totally unappreciated during their release, all they need is time—and a cult following. Eventually, the consensus around a cult film will change; it’s a frequent occurrence. To offer up just one egregious example: The New York Times once referred to George Miller’s Mad Max as “ugly and incoherent.” While Event Horizon doesn’t exactly have the reputation of Miller’s classic, the tides have unquestionably turned in its favor. ( Event Horizon recently popped up on Ringer contributor Adam Nayman’s “Ten Movies That Are Better Than You’ve Heard,” and I promise I had nothing to do with that.)

Still, it can be hard to gauge a film’s cult following and its reputation without quantifiable metrics—enthusiastic posts on the internet take you only so far. So consider this confirmation that Anderson’s movie has transcended its tepid release: Last year, Amazon and Paramount Television announced that they’re working on an Event Horizon TV series , which will be helmed by Adam Wingard. (Anderson tells me he is not involved with the project.) Even with Bezos’s money, you don’t green-light a horror series set in outer space unless you believe there’s an audience for it.

But for the most part, the cult status of Event Horizon centers on Anderson’s vision—and also what could have been. In an era when enough DC fanboys can convince Warner Bros. to actually #ReleaseTheSnyderCut on HBO Max , horror enthusiasts are still clamoring for the #AndersonCut , if you will, of Event Horizon . Because the director left so much gnarly material out of the final version, the prospect of what isn’t in the film has become the stuff of legend. Mostly—infamously—I’m referring to the visions of hell.

Event Horizon ’s most enduring imagery, outside of Sam Neill removing his eyes and going buck wild on Captain Miller and his team, has to do with the final video log from the ship’s original crew. When the old footage is restored, Miller and Co. find out what really happened to those poor souls. After engaging the ship’s gravity drive for faster-than-light travel, everyone aboard goes berserk—mutilating one another in a bloody orgy of graphic sex and violence. The actual footage gets around 15 seconds of screen time—I would not recommend slowing it down for all the diabolical details—before Captain Miller says thusly, “We’re leaving.” (Fishburne is low-key hilarious throughout the movie, playing it cool in a situation in which someone has every right to freak out.)

That hell footage is, to put it mildly, extremely fucked up—and is grimly funny if you watch it knowing that Paramount assumed it simply had a darker version of Star Trek on its hands. Since the Los Angeles–based studio was so fixated on Titanic , and Anderson was filming Event Horizon in London, there wasn’t much oversight from Paramount on the visions-of-hell sequences, which he filmed on the weekends with a reduced unit. “I think that maybe they thought we were shooting close-ups of people pressing buttons or something like that,” Anderson says. “Maybe they never saw it until the test screening, and then—they were shocked. I’ll definitely say that.”

Extras needed to be nude on top of all the violence, so some adult film performers were hired. Casting requirements for the sequences got only narrower from there. “I remember there’s a scene where somebody gets some of their teeth knocked out,” Anderson explains. “So we needed people who had teeth missing and were wearing dentures, we then put in these stunt dentures that could get knocked out. So there was some very specific casting for some of it.”

There’s an almost mythic (demonic?) quality to the visions-of-hell sequences, especially because there’s a good chance we’ll never get to see the majority of what was shot. Event Horizon ’s extra film footage was dumped in—this is somehow true—a Transylvania salt mine , and when the contents were discovered nearly a decade later, the material had degraded. As much as Anderson would be interested in making a director’s cut of the movie, and is aware of the internet hype around such an endeavor, it’s probably not possible.

I stress probably , though, since there’s a glimmer of hope in the form of a single VHS that contains alternate footage. “Lloyd Levin, who was one of the producers on [ Event Horizon ], has the VHS, a different cut of the movie,” Anderson says. “The last time we were on the same continent together, he had the VHS cassette, but neither of us had a VHS player. We couldn’t watch it, so I think he still has that. I don’t know whether—I think someone has to do some detective work.” (Counterpoint: Get a VHS player, and when it’s safe again to travel, go and check it out yourself, man; it’s your movie!) Mysterious VHS tape notwithstanding, the home video company Shout! Factory is also planning to release a special collector’s edition Blu-ray of Event Horizon in 2021 through its retro horror label, but even its official announcement on Facebook includes an open invitation for fans to offer leads on how to unearth any additional footage. Though admirable in its efforts, a company hoping to outsource bonus content from folks on the internet doesn’t inspire much confidence.

But while an extended cut of Event Horizon would be a fascinating document, what really makes the horror work in the movie’s current form is how it strikes a balance between gruesome imagery and leaving things to the audience’s imagination. Event Horizon suppresses enough of the hell dimension’s terrors and what the ship’s original crew ends up doing to one another that your mind takes care of the rest. Anderson posits that a gorier cut of Event Horizon might have weakened the film’s scares. After all, we each have a different relationship to fear—and what exactly frightens us. It’s hard to comprehend what being doomed for eternity in hell would even be like. Or, as Dr. Weir puts it: “Hell is only a word. The reality is much, much worse.”

For all the tempting what-ifs with the director’s cut enhancing the on-screen horrors, Sam Neill’s committed performance is a big reason the Event Horizon that we have rules so hard. With only 90-odd minutes to run through, Dr. Weir’s descent into a murderous frenzy is startling and full of unforgettable moments. In addition to the shocking sight of the character after removing his eyes, Dr. Weir vivisects Jason Isaacs’s medical doctor DJ in a macabre sequence that required a full body cast of the actor with, per Anderson, “anatomically correct intestines.” (When Isaacs asked to keep his flayed replica after the shooting, the director refused and called him a “twisted mind.”) It’s also one of the key reasons something as wicked as Event Horizon holds rewatch value: As long as you can stomach the gore, Dr. Weir’s pivot from sympathetic scientist to full-blown emissary of hell is a campy tour de force.

But if the notion of Twitter king Sam Neill terrorizing people in space is upsetting, well, that was the point. Anderson was aware of the actor’s horror bona fides through his roles in Omen III: The Final Conflict and In the Mouth of Madness , but knew his cozy reputation with mainstream audiences could be weaponized. “I felt that Sam Neill, in people’s consciousness, he was the good guy from Jurassic Park ,” Anderson explains. “He was the man who saved the children, he was America’s hero. And I loved the idea of taking that man who’s so solid and so dependable and reliable, who saves children from dinosaurs, and going, ‘You know what? You can’t trust him, because he’s just insane.’ And I thought Sam did a tremendously good job.”

It’s an indelible character from an indelible movie, one that’s persisted long after its release. From the video game series Dead Space to lesser films like Pandorum and The Cloverfield Paradox , Event Horizon ’s imprint is unmistakable, and the fact Amazon is making a TV adaptation should only expand its influence in pop culture. “Some things that maybe hindered Event Horizon commercially when it came out have actually become its strength and the reason why it’s enduring,” Anderson says. You might not see anyone dressed as Eyeless Sam Neill for Halloween—in fact, please report any parents who subject their kids to such a thing—but Event Horizon has the kind of heightened, memeable resonance that feels even more appropriate in 2020.

Regardless of the context in which it was released, a mid-budget, R-rated movie about scientists accidentally opening a gateway to hell in the middle of outer space might be a hard sell. But even when Event Horizon bombed in 1997 and was flayed by critics as brutally as Jason Isaacs aboard a spaceship, Anderson knew he succeeded with the gothic horror story he set out to make. Reception be damned, the filmmaker was proud of the movie—it was unmistakably his.

Besides, there were some big names in the industry who, even back then, realized Anderson had created something special. “I showed it to Kurt Russell, because I was about to do a movie with him,” Anderson says. “When he came out, he said, ‘You know, I don’t care what people think of this movie now. In 15 years’ time, this is the movie you’re going to be glad you made.’ And he was right.”

Next Up In Movies

- ‘Short n’ Sweet,’ Lana Del Rey’s Airboat BF, ‘Chimp Crazy,’ and More!

- The Michael Keaton Movie Mount Rushmore

- The Most Iconic Moment of the ‘Lord of the Rings’ Movies

- Not Another Presidential Biopic

- Summer Box Office Winners, Losers, and Head-Scratchers

- ‘Purple Rain’ With Bill Simmons and Wesley Morris

Sign up for the The Ringer Newsletter

Thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

‘Rings of Power’ Season 2, Episodes 1-3 Deep Dive

Mal and Jo review their impressions and favorite moments from the first three episodes

Ringer-Verse Recommends: August 2024

The ‘House of R’ and Ringer-Verse crews bring you their latest fandom favorites

Alexis Bellino and Johnny J Are Engaged! Plus, ‘Orange County’ and ‘Dubai.’

Rachel, Chelsea, and Callie dish on the latest news in the Bravo world

Second-Chance Sophomores, Future Final Four Sites, and College Football’s Return With League Him Founder Jacob Myers

Tate Frazier is joined by Jacob Myers to discuss second-chance sophomores and talk about college football, the Final Four, and more

The Seven Biggest Story Lines of the WNBA’s Stretch Run

How far can Caitlin Clark carry the Fever? Are the Sky doomed? And will one player see her history-making performances go to waste? Here’s what to watch as the playoffs approach.

Jacoby Brissett Gets the Starting Job. Plus, NFL Futures With Tate Frazier.

Brian discusses the news that Jacoby Brissett will start at QB for the Pats, and why the team went with Brissett over Drake Maye

The Untold Truth Of Event Horizon

The 1997 sci-fi/horror hybrid Event Horizon is a singularly odd film. It's permeated by an atmosphere of dread, and it features some great performances, as well as some genuinely shocking violence. But one gets the feeling that it isn't quite the film that its director, future Resident Evil series mastermind Paul W.S. Anderson, intended.

The flick tells the story of the Lewis and Clark , a rescue vessel sent to investigate after the spaceship Event Horizon , which had vanished en route to a mysterious destination seven years prior, makes a sudden reappearance, broadcasting a bizarre distress call. Led by Captain Miller (Laurence Fishburne) and Lieutenant Starck (Joely Richardson), the Lewis and Clark encounters the ship, and its crew are forced to board the Event Horizon after an accident damages their own vessel.

What they find on board is disturbing to the extreme, and soon, members of the crew — including Dr. Weir (Sam Neill), the designer of the original doomed ship — begin acting very, very strangely. Thanks to its gruesome imagery and terrifying tone, the film has attained cult status in the years since its release. But the behind-the-scenes story is just as fascinating as the film. So let's take a look back at the troubled production and weird history of a very weird film. Here's the untold truth of Event Horizon .

The director turned down an iconic movie to make Event Horizon

In the mid-'90s, Paul W.S. Anderson was still a relatively green director. His debut feature, the 1994 crime actioner Shopping, was notable mostly for featuring a young Jude Law in his first leading role, and the British flick hardly registered a blip with stateside audiences. But his second film, the 1995 video game adaptation Mortal Kombat , proved to the Tinseltown brass that Anderson could make a profitable genre film on a tight budget. And as such, he was given a choice of projects for his next feature.

One of those projects was X-Men , which would eventually kick off the modern superhero genre under the direction of Bryan Singer. According to Event Horizon 's DVD commentary , Anderson was offered the director's chair on X-Men , but he turned it down in favor of making the horror flick. He does admit that it "probably wasn't a good career choice," but he just didn't want to make another PG-13 film. "I definitely had something dark and scary in my psyche to get out," he explained. And so he gravitated toward Event Horizon , the first feature screenplay from scribe Philip Eisner , and he passed on the opportunity to introduce the world to Wolverine and his mutant pals.

Event Horizon was almost an Alien rip-off

Event Horizon 's original screenplay needed a little surgery before going in front of the cameras. This is because, in the original version of the script presented to Anderson by studio Paramount, the Event Horizon had brought back something a little too familiar from whatever cursed dimension it had traversed — alien monsters. In the first script, a bunch of evil extraterrestrials had slaughtered the vessel's crew and were hungry for more.

However, Anderson had a something a bit more unique in mind. He wanted to tell a ghost story more along the lines of The Shining , in which the ship itself had attained a wicked form of sentience (via Den of Geek ). Anderson was given free rein by the studio to reshape the story as he saw fit, as well as a $60 million budget to bring his vision to life. The director basically took a scalpel to Eisner's script, jettisoning the elements that would've made it little more than a slightly spookier Alien rip-off in favor of an altogether more disturbing angle.

Anderson was influenced by a classic Russian sci-fi movie

In reworking Event Horizon to his liking, Anderson drew heavily on Solaris , a 1972 feature from the Soviet Union based on the 1961 novel by Polish author Stanislaw Lem. Solaris is a meditative, dreamy movie — an art film with few true horror elements — but it's easy to see the influence of its plot all over Event Horizon . In Solaris , a psychologist is sent to examine the crew of a space station that's been orbiting the titular planet for decades. He finds a borderline hostile, uncooperative crew inhabiting a station that's been dangerously neglected, and he soon comes to find that his friend, a scientist who accompanied the original crew, has committed suicide. Then, he begins to see people roaming the halls of the station who aren't supposed to be there — including his late wife.

More than one critic, including the great Roger Ebert , recognized the influence of Solaris on Event Horizon upon its release, and Anderson himself has acknowledged as much. In a 2014 interview with Grantland , the director said, "I love the movies like Solaris , the original Solaris — the script [for Event Horizon ] clearly draws from [that film]. Those kind of meditative European films that are unsettling but don't really play to a modern audience. By adding that kind of visceral thrill, that's making it my own." Interestingly, Solaris received the Hollywood remake treatment in 2002, with George Clooney in the lead role and Steven Soderbergh in the director's chair. Sadly, the film flopped mightily, due in part to a confusing marketing campaign .

Anderson used Gothic architecture to build the film's look

Anderson's Solaris -influenced tweak to Philip Eisner's screenplay was diabolically simple. The Event Horizon , designed to travel at faster-than-light speeds by breaching the space-time continuum, had traveled somewhere that it was never meant to go, and in doing so, it had become ... infected. While it's never made crystal clear, the implication is that the ship has literally been to Hell and back. And since that basically made the ship itself the villain of the film, it needed an appropriately ominous design.

Talking with The Ringer , Anderson recalled that for the design of the ship's interior, he drew from Gothic architecture in general and one iconic historical site in particular. "I wanted to do something different that hadn't been done in spaceships before, and because we were telling a Gothic horror story, I reached back in time," the director said. "Using an architectural cam program, we basically built Notre Dame Cathedral in the computer, and then we pulled it apart, and we used different elements of it to build the Event Horizon. So, the towers from Notre Dame became the engine thruster pods."

Thanks to the flick's beefy budget, the entire interior of the Event Horizon was constructed on a cavernous sound stage, and once it was finished, Anderson knew he was on the right track. "[Cast members] would go, 'I love working with you, Paul, but I hate coming to work. It was just horrible," Anderson remembered, going on to explain, "It was actually the sets themselves because the crew couldn't have been nicer. But there was a disturbing vibe. I really felt like we created a very physical haunted house for the actors to interact with."

Event Horizons' director of photography helped cement a 'techno-medieval' aesthetic

Anderson would need a veteran of genre films to effectively shoot his bizarre sets, and he got one in Adrian Biddle, who'd shot such instantly iconic films as Aliens , The Princess Bride , and Thelma & Louise . Biddle immediately understood what Anderson was going for, and with the help of the director and production designer Joseph Bennett, he carefully selected a lighting scheme that would make the Event Horizon appear appropriately futuristic and sterile in cold artificial light ... and take on a whole new personality when bathed in dim light and darkness.

Anderson recalled his DP's contribution in a 2020 chat with American Cinematographer magazine. "We spent a lot of time coming up with a design concept, which we called 'techno-medieval,'" he said. "When the lights are on, everything looks very technological and very spaceship-like. But when the lights go off and the haunting begins, you start looking at the shapes, and the architecture is actually very medieval. We extended that techno-medieval design idea into as many aspects of the picture's look as possible, without rubbing the audience's nose in it."

Biddle opted to use colored gels to augment the film's lighting, a time-honored technique that had fallen out of favor to further heighten the film's sense of unease. "I used some sepia brown coming up from the floor to make viewers uncomfortable on the ship, as well as flashes of red. I also used a lot of green," he remembered. "Cinematographers generally shy away from green, because it's not very pleasant, but on Event Horizon I used gels to produce that nasty, horrible green you get from fluorescents. ... I was going for that kind of an effect, to convey the idea that something not very good is lurking in the ship."

Event Horizon was almost sunk by Titanic