57 UNDERSTANDING TOURIST BEHAVIOR IN A CHANGING ENVIRONMENT – Contributions by Astrid Kemperman

The travel and tourism industry is among the most affected sectors by the Covid-19 pandemic, with a massive fall in international tourism demand. While the industry is currently recovering, the World Tourism Organization argues that this fall in demand offers the opportunity to rethink the tourism sector and build back better towards a more sustainable, inclusive, and resilient sector that ensures that the benefits of tourism are enjoyed widely and fairly (UNWTO, 2021). Over the last decades, it has become clear that the growth of tourism brings significant challenges with it and is itself also influenced by for example climate change, pollution, decreasing natural resources, growing populations, and local and cultural differences. The negative environmental impacts of tourism are substantial: tourism puts stress on local land use, can lead to increased pollution, and more pressure on endangered species and the natural habitat. A more sustainable tourism approach would mean taking into account the current and future economic, social and environmental impacts, the preferences and needs of visitors, the industry, the environment, and host communities (UNWTO, 2021).

At the same time, recent technological and digital innovations also change the way people live, work, travel, interact with one another, and how they spend their free time. The borders between the digital, social, and physical environment are more and more intertwined. Technological advances, information dissemination, the influence of social networks, and increasing available free time and monetary budgets have further strengthened the need to create sustainable development opportunities for the tourism industry to support and improve efficient destination planning, management, and local community empowerment and inclusiveness. Moreover, as argued by Gretzel and Koo (2021), these technological developments lead to a convergence of urban residential and touristic spaces, and there is value in merging so-called smart tourism and smart city planning and management development goals to serve both residents and tourists in the best possible ways.

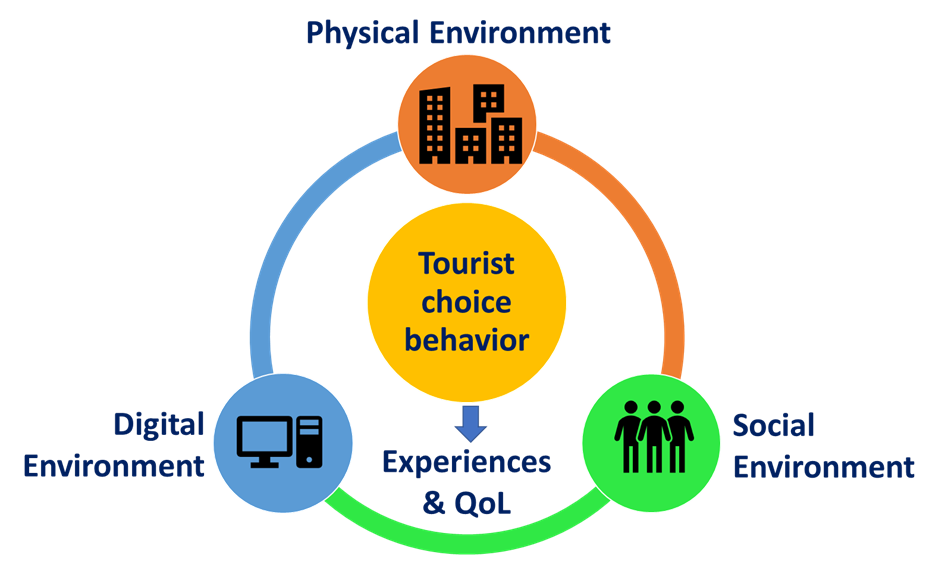

Research is needed to test the possible impact of new technology on tourists, their needs, preferences and activities, social relationships, and interaction with the environment. These considerations drive my general research aim: to develop a deeper understanding of individuals’ needs, preferences, and spatial activity patterns within the context of the digital, social, and physical environment to help find solutions for these challenging problems. In this chapter, a concise overview of my research, from the past to present and some new ideas are presented and discussed, as shown in figure 1: investigating tourist choice behavior within a changing digital, social and physical environment to support planning and design of environments that enhance tourist experiences and quality of life.

Facets of tourist choice behavior

Central in my research over the years is understanding and adding to knowledge on tourist choice behavior, and I have been doing so taking a quantitative research approach using advanced data collection methods (e.g., dynamic stated choice experiments) and modeling approaches (e.g., discrete choice modeling, Bayesian Belief Network models). Tourists make a variety of choices including whether or not to travel, destination choice (e.g., Kemperman, Borgers & Timmermans, 2002b), transport mode choice (e.g., Grigolon, Kemperman & Timmermans, 2012c), accommodation choice (e.g., Randle, Kemperman & Dolnicar, 2019), trip duration choice (e.g., Kemperman, Borgers, Oppewal & Timmermans, 2003), and what activities to undertake while at a specific destination (e.g., Kemperman, Joh, & Timmermans, 2004). However, when explaining and predicting tourist choice behavior a variety of unique properties need to be taken into account. Over the years I have investigated some of these aspects.

First, compared to other types of choices like transport mode choice, tourists are inclined to show variety-seeking behavior in their choices over time, meaning that a time-invariant preference function is not reasonable (Kemperman, 2000). Variety seeking behavior in tourists may be influenced by a variety of factors such as availability of choice alternatives or changes in their characteristics, differences in decision-making contexts, different choice motivations, different travel party group composition or travel companions, and in general a basic desire for novelty (Kemperman, Borgers, Oppewal and Timmermans, 2000). Specifically, a discrete choice model of theme park behavior including seasonal and variety-seeking effects is proposed and estimated and the external validity of the model is assessed leading to accept the hypothesis that tourists differ in their preferences for theme parks by season and show variety-seeking behavior over time (Kemperman, Borgers & Timmermans, 2002b).

In general, tourist choices, certainly compared to for example commuter choices, are made less frequently, represent high-involvement decisions, often include multiple choice facets, the decision process may take longer, and they might be based on well-established long-term agendas (Grigolon, 2013). A portfolio choice experiment concerning the combined choice of destination type, transport mode, duration, accommodation, and travel party for vacations is developed (Grigolon, Kemperman & Timmermans, 2012b). Specifically, the influence of low-fare airlines on the portfolio of vacation travel decisions of students is investigated. The findings confirm earlier studies that conclude that travel-related decisions for tourists, in general, are multi-faceted and not only related to the destination itself (e.g., Dellaert, Ettema, & Lindh, 1998; Jeng & Fesenmaier, 1997; Woodside & MacDonald, 1994).

In another study, based on revealed data about vacation history in terms of the long holidays of a sample of students, interdependencies in the vacation portfolios and their covariates are explored using association rules (Grigolon, Kemperman & Timmermans, 2012a). The portfolios include joint combinations of destination, transport mode, accommodation type, duration of the trip, length of stay, travel party, and season. Results show and confirm dependencies between vacation portfolio choice facets and their covariates. These insights provide a better understanding of tourist choice behavior and the context in which choices are made and can support policy and planning decision-making.

Tourist activity choices

When tourists are at a destination or in a city there is the timing and sequencing of tourists’ activity choices. Over-usage and congestion of specific attractions or facilities are difficult to avoid and may cause severe problems for a destination or city. For destination planning and management, it is important to understand how tourists behave in time and space, how the demand for various activities and attractions fluctuate over time, and how they can be accommodated and directed.

One of my first studies on this topic (Kemperman, Borgers & Timmermans, 2002a) introduces a semi-parametric hazard-based duration model to predict the timing and sequence of theme park visitors’ activity choice behavior that is estimated based on observations of tourist activity choices in various hypothetical theme parks. The activities include a description of the activity/attraction as well as their waiting time, activity duration, and location. The main findings support the prediction of how the demand for various activities is changing during the day and how the visitors are distributed over the activities in the park during the day. This information is relevant for visitor use planning to optimize the theme park experience.

In another study on visitors’ activities undertaken while tourists are at a destination, we focus on interrelated choices of tourists, multi-dimensional activity patterns as opposed to particular isolated facets of such patterns (Kemperman, Joh, & Timmermans, 2004). Moreover, in this study, it is tested whether activity patterns of first-time visitors tend to differentiate from the activity patterns of repeat visitors, mediated by their use of information. Differences between the two groups are assumed to be reduced when first-time visitors use information about the available activities and the spatial layout of the theme park. Specifically, the sequence alignment method is applied to capture the sequence of conducted activities. We conclude that the activity patterns of the two groups do differ, first-time visitors follow a very strict route in the park as indicated by the theme park, while repeat visitors have a more diverse order in their activity pattern. However, the difference between the two groups is reduced when first-time visitors use information about the available activities and the spatial layout of the park.

In an aim to measure and predict tourists’ preferences for combinations of activities to participate in during a city trip, a personalized stated choice experiment is developed and binary mixed logit models are estimated on the choice data collected (Aksenov, Kemperman & Arentze, 2014). An advantage of this approach is that it allows estimation of covariances between city trip activities indicating whether they would act as complements or substitutes for a specific tourist in his/her city trip activity program. The model provides information on combinations of activities and themes that tourists prefer during their city trip and that can be used to further fine-tune the recommendations of city trip programs and optimize the tourist experience.

As shopping is one of the most important activities for tourists, we also investigate shopping route choice behavior in a downtown historic center, including the motivation for the shopping trip, familiarity with the destination, and whether the shopping route through the downtown area is planned or not before the visit (Kemperman, Borgers, & Timmermans, 2009). A model of tourist shopping behavior is proposed and estimated to investigate differences in route choice behavior of various types of tourist shoppers. The results indicate that shopping supply and accessibility, some physical characteristics, and the history of the route followed are important factors influencing route choice behavior. Furthermore, it can be concluded that shopping motivations, familiarity with the area, and planning of the route affect tourist route choice behavior. The model allows investigating the effects of environmental characteristics on route choice behavior and assessing various future planning scenarios, such as changes in physical aspects in the downtown area, or changes in the supply of shops to optimize visitors’ shopping trips.

Social and physical environment and tourist choice behavior

The social environment including the social relationships and cultural milieus within which tourists interact and make their choices is intertwined with the physical, natural, and built environment in which tourists travel and their activities take place.

First, a study in which we explore children’s choices to participate in recreational activities and the extent to which their choices are influenced by individual and household socio-demographics, and characteristics of the social and physical environment (Kemperman & Timmermans, 2011). Travel and activity diaries of a large sample of children aged 4-11 years old in the Netherlands are used to collect data on out-of-home recreational activity choices and this data is merged with measures describing the social and physical living environment. A Bayesian belief network modeling approach is used to simultaneously estimate and predict all direct and indirect relationships between the variables. Results indicate that recreational activity choices are, among others, directly related to the socio-economic status of the household, the perceived safety of the neighborhood, and the land use in the neighborhood. Planners and designers are recommended to find a good land use mix, and specifically, make sure that they focus their attention on safety issues to stimulate children’s recreational activity choices.

In a more recent study, we investigate with a stated choice experiment how different presentations of cause-related corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives affect holiday accommodation choices, with a specific focus on the relative importance of tourist involvement, the message-framing, and the donation proximity (Randle, Kemperman, & Dolnicar, 2019). In a tourism context, we see that an increasing number of organizations implement so-called social corporate responsibility (CSR) initiatives, meaning they give some of their benefits back to the local community, society and, or the environment and it is of interest to see whether tourists take these initiatives into account when making their choices and how messages are valued. We found that different market segments are affected differently by these SCR initiatives when choosing their holiday accommodation. Specifically, there is one CSR-sensitive segment that cares about nature and the natural landscape, experiencing nature intensely, and efforts to maintain unspoiled surroundings and scores higher on community involvement than other segments. In general, it is found that negative message framing is the most promising option in terms of positively influencing tourist choices. It is concluded that although CSR initiatives do not appear to have a consistently positive effect on all tourist accommodation choice behavior, neither do they negatively affect demand. Specifically, it is advised to tailor CSR messages such that they are most effective in influencing the SCR-sensitive tourist segment.

Tourism can have an enormous environmental impact, and specifically, air travel negatively contributes to global carbon emissions. A voluntary carbon offset program supports airlines to take proactive measures to reduce the environmental impact. We have tested, using a stated choice experiment, the effectiveness of different communication messages to increase voluntary purchasing of carbon offsets by air passengers (Ritchie, Kemperman, & Dolnicar, 2021). Results indicate that tourists who book their flights prefer carbon offset schemes that fund local programs over international ones, that are effective in mitigating emissions, and are accredited. The willingness to pay for carbon offsets when booking for a group is lower than when booking an individual flight for oneself. Moreover, the tourist market can be divided into different segments with their characteristics, including age, employment status, frequent flyer membership, and flight behavior. Therefore, it is important to target the segments for aviation carbon offsetting by matching certain types of attributes and present an optimal program to each of the segments.

Integration of the digital environment in tourist choice behavior

Nowadays digital technologies can support tourists in making their choices, planning their trips, and optimizing their experiences (e.g., Buhalis, 1998; Gretzel, Mitsche, Hwang & Fesenmaier, 2004; Kemperman, Arentze, & Aksenov, 2019; Rodriguez, Molina, Perez & Caballero, 2012; Steen Jacobsen & Munar, 2012). We introduce this concept of ‘smart routing’ in the development of a recommender system for tourists that takes into account the dynamics of their personal user profiles (Aksenov, Kemperman, & Arentze, 2016). This smart routing concept relies on three levels of support for the tourist: 1) programming the tour (selecting a set of relevant activities and points of interests to be included in the tour, 2) scheduling the tour (arranging the selected activities and point of interests into a sequence based on the cultural, recreational and situational value of each) and 3) determining the tour’s travel route (generating a set of trips between the activities and point of interests that the tourist needs to perform to complete the tour). This approach aims to enhance the experience of tourists by arranging the activities and points of interest together in a way that creates a storyline that the tourist will be interested to follow and by reflecting on the tourists’ dynamic preferences.

For the latter, an understanding of the influence of a tourist’s affective state and dynamic needs on the preferred activities is required (Arentze, Kemperman, & Aksenov, 2018). Finally, the activities and points of interest are connected by a chain of multimodal trips that the tourist can follow, also in relation to their preferences and dynamic needs. Therefore, each tour can be personalized in a ‘smart’ way optimizing the overall experience of the trip. In the study, the building blocks of this concept are discussed in detail and the data involved, and finally, a prototype of the recommender system is developed.

C onclusion and future research

This chapter gives an overview of research that I have worked on over the years in collaboration with other researchers to develop a deeper understanding of tourists’ choice behavior and to generate insights and provide support for policy, planning, and managerial decision making in finding answers to the challenges the tourism industry and environment are facing. Specifically, examples of research are presented that tested in different ways facets of tourists’ needs, preferences, and spatial activity patterns within the context of a changing digital, social and physical environment.

Based on this overview some avenues for future research, in line with the presented framework in Figure 1, can be given. First, the studies presented show how tourist choices are influenced by their social and physical environment and that in understanding these choices it is important to take these aspects into account. Specifically, the social environment or social influence by family members, peers, or colleagues might also be an important additional explanatory facet in explaining tourist choices, for example in understanding and promoting the choice for sustainable tourist behavior. Research has also indicated that role of social media, online reviews, and social influencers have become increasingly important in the choices tourists make, and including the influence of someone’s social network, colleagues, peers, and family members in predicting tourist choice behavior is an interesting research opportunity (Kemperman, 2021).

The digital and technological developments support and improve other ways of data collection, for example by using virtual reality, simulators, or eye-tracking (e.g., Cherchi and Hensher, 2015; Kemperman, 2021). Tourists are often unfamiliar with a specific destination or tourist service, and therefore presenting them with more visual, virtual reality or interactive choice options might be of interest to better measure their preferences and choice behavior. Moreover, virtual or augmented reality environments also allow testing the effects of interventions on tourist preferences and behavior before they are actually implemented. This is an advantage, specifically when high investments are involved.

Moreover, technological innovations support the collection of more and more types of so-called big data and this data can be very useful in tourism research (Li, Xu, Tang, Wang, & Li, 2018). Big data sources for tourism research come in a variety of forms, such as user-generated data (e.g., tweets, online photos), device data (e.g., GPS data, mobile phone data), and transaction data (e.g., online booking data, customer cards). These types of smart big data sources might be used to understand how inner-city visitors’ activity choices emerge and evolve in space and time to provide city managers and planners with important information for future management and planning such as visitor flows and clusters, and interesting locations (e.g., Beritelli, Reinhold & Laesser, 2020).

Finally, to conclude, there is a challenge for more research and evidence to further expand knowledge on tourist choice behavior and support optimizing tourists’ experiences and quality of life.

Written by Astrid Kemperman, Eindhoven University of Technology, The Netherlands

Aksenov, P., Kemperman, A.D.A.M., & Arentze, T.A. (2014). Toward personalized and dynamic cultural routing: A three-level approach. Procedia Environmental Sciences, 22 , 257-269.

Aksenov, P., Kemperman, A., & Arentze, T. (2016). A Personalised Recommender System for Tourists on City Trips: Concepts and Implementation. In De Pietro, G., Gallo, L., Howlett, R.J., Jain, L.C. (eds): Intelligent Interactive Multimedia Systems and Services 2016 , Springer International Publishing Switzerland, 525-535.

Arentze, T., Kemperman, A. & Aksenov, P. (2018). Estimating a latent-class user model for travel recommender systems. Information Technology & Tourism, 19( 1-4), 61-82.

Beritelli, P., Reinhold, S., & Laesser, C. (2020). Visitor flows, trajectories and corridors: Planning and designing places from the traveler’s point of view. Annals of Tourism Research, 82, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102936.

Buhalis, D. (1998). Strategic use of information technologies in the tourism industry. Tourism Management, 19 (5), 409-421.

Cherchi, E., & Hensher, D. A. (2015).Workshop synthesis: Stated preference surveys and experimental design, an audit of the journey so far, and future research perspectives. Transportation Research Procedia, 11 , 154–164.

Dellaert, B. G. C., Ettema, S. D. F., & Lindh, C. (1998). Multi-faceted tourist travel decisions: A constraint-based conceptual framework to describe tourists’ sequential choices of travel components. Tourism Management, 19, 313–320.

Gretzel, U. & Koo, C. (2021). Smart tourism cities: a duality of place where technology supports the convergence of touristic and residential experiences. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 26 (4), 352-364.

Gretzel, U., Mitsche, N., Hwang, Y.H., & Fesenmaier D.R. (2004). Tell me who you are and I will tell you where to go: Use of travel personalities in destination recommendation systems. Information Technology & Tourism, 7 , 3–12.

Grigolon A.B., Kemperman A.D.A.M., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2012a). Exploring interdependencies in students’ vacation portfolios using association rules. European Journal of Tourism Research, 5( 2), 93-105.

Grigolon A.B., Kemperman A.D.A.M., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2012b). The influence of low-fare airlines on vacation choices of students: Results of a stated portfolio choice experiment. Tourism Management, 33 , 1174-1184.

Grigolon A.B., Kemperman A.D.A.M., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2012c). Student’s vacation travel: A reference dependent model of airline fares preferences. Journal of Air Transport Management, 18 (1), 38-42.

Grigolon, A. (2013). Modeling Recreation Choices over the Family Lifecycle. Ph.D Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven.

Jeng, J.M. & Fesenmaier, D.R. (1998), Destination Compatibility in Multidestination Pleasure Travel. Tourism Analysis, 3 , 77-87.

Kemperman A.D.A.M., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2011). Children’s recreational physical activity. Leisure Sciences, 33 (3), 183-204.

Kemperman A.D.A.M., Borgers A.W.J., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2002a). A semi-parametric hazard model of activity timing and sequencing decisions during visits to theme parks using experimental design data. Tourism Analysis, 7, 1-13.

Kemperman A.D.A.M., Borgers A.W.J., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2002b). Incorporating Variety-Seeking and Seasonality in Stated Preference Modeling of Leisure Trip Destination Choice: A Test of External Validity. Transportation Research Record, 1807 , 67-76.

Kemperman A.D.A.M., Borgers A.W.J., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2009). Tourist shopping behavior in a historic downtown area. Tourism Management, 30 (2), 208-218.

Kemperman A.D.A.M., Borgers A.W.J., Oppewal H. & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2003). Predicting the duration of theme park visitors’ activities: An ordered logit model using conjoint choice data. Journal of Travel Research, 41 (4), 375-384.

Kemperman A.D.A.M., Borgers A.W.J., Oppewal H., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2000). Consumer Choice of Theme Parks: A Conjoint Choice Model of Seasonality Effects and Variety Seeking Behavior . Leisure Sciences, 22 , 1-18.

Kemperman A.D.A.M., Joh C.H., & Timmermans, H.J.P. (2004). Comparing first-time and repeat visitors activity patterns. Tourism Analysis, 8 (2-4), 159-164.

Kemperman, A. (2000). Temporal aspects of theme park choice behavior. Modeling variety seeking, seasonality and diversification to support theme park planning, Ph.D Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven.

Kemperman, A. (2021). A review of research into discrete choice experiments in tourism – Launching the Annals of Tourism Research curated collection on discrete choice experiments in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 87, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103137.

Kemperman, A., Arentze, T., & Aksenov, P. (2019). Tourists’ City Trip Activity Program Planning: A Personalized Stated Choice Experiment. In Artal-Tur, A., Kozak, N., Kozak, M. (eds): Trends in Tourist Behavior: New Products and Experiences in Europe , Springer, Springer Nature Switzerland

Li, J., Xu, L., Tang, L., Wang, S., & Li, L. (2018). Big data in tourism research: A literature review. Tourism Management, 68 , 301-323.

Randle, M., Kemperman, A., & Dolnicar S. (2019). Making cause-related corporate social responsibility (CSR) count in holiday accommodation choice. Tourism Management, 75 , 66-77.

Ritchie, B.W., Kemperman, A., & Dolnicar, S. (2021). Which types of product attributes lead to aviation voluntary carbon offsetting among air passengers? Tourism Management, 85, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104276 .

Rodríguez, B., Molina,J., Pérez, F., & Caballero, R. (2012). Interactive design of personalised tourism routes. Tourism Management, 33 (4), 926-940.

Steen Jacobsen, J.K., & Munar, A.M. (2012). Tourist information search and destination choice in a digital age. Tourism Management Perspectives, 1 (1), 39-47.

UNWTO (2021). COVID-19 response. Retrieved from https://www.unwto.org/tourism-covid-19

Woodside, A.G. & MacDonald, R. (1994), General System Framework of Customer Choice Processes of Tourism Services, in R. Gasser and K. Weiermair (eds.), Spoilt for Choice, Kultur Verlag, Austria.

Women’s voices in tourism research Copyright © 2021 by The University of Queensland is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Tourists behaving badly: how culture shapes conduct when we’re on holiday

Assistant Professor, Hong Kong Polytechnic University

PhD researcher, Hong Kong Polytechnic University

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

There appears to be increasing tension between tourists and residents around the world, with the former often blamed for behaving inappropriately and disturbing locals. Protests against tourist behaviour have erupted in Barcelona , Venice and Hong Kong .

In Hong Kong, tourists are blamed for being noisy, inconsiderate, urinating in public, buying up necessities such as baby milk powder, and generally not following local customs. Chinese tourists, in particular, face harsh criticism in Hong Kong as well as in Thailand .

In Spain, British tourists are often blamed for poor behaviour.

But tourists’ ethics are rarely studied, and many questions about their behaviour remain unanswered. These include whether tourists have different moral values than local residents; if visitors from different parts of the world have different moral values; and whether people are more likely to participate in morally dubious activities while on holidays than where they live.

What we did

In a recently published study , we suggest that, at least in Hong Kong, there may indeed be differences between ethical judgements of tourists from different regions and local residents.

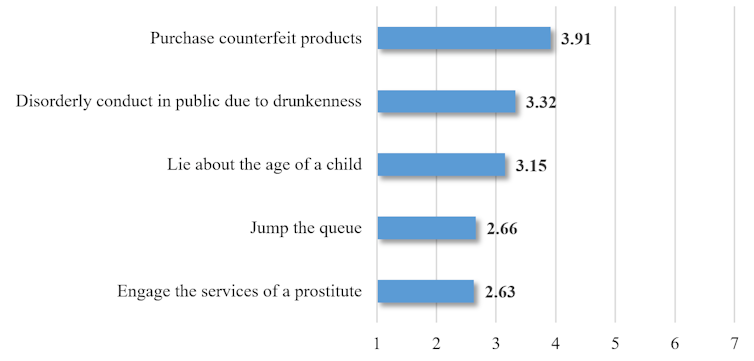

We undertook a survey of mainland Chinese tourists, Western tourists and Hong Kong residents, and asked to identify how morally acceptable five different scenarios were.

Our scenarios were: purchasing counterfeit products, disorderly behaviour in public due to drunkenness, jumping queues, lying about a child’s age (to get discounts) and using the services of a prostitute.

We then applied a Multidimensional Ethics Scale to find out more precisely how acceptable these scenarios were to respondents. This widely-used scale uses several normative ethics theories to understand ethical judgements.

We then asked the respondents whether they were likely to engage in these activities at home and on holidays.

Fish out of water

The case of tourist behaviour is especially interesting for debates about ethical decision-making. At home, we may be bound to behave in a certain manner due to societal pressures. We may feel judged by relatives, friends or colleagues. And we may think that somebody who knows us will easily find out about our misbehaviour. Our actions may have long-lasting consequences.

But these pressures are removed when we travel overseas to places where no one knows us and where we don’t stay for long. Tourism, then, may be thought of as an egoistic and indulgent activity.

At least, that’s the theory.

Overall, engaging the services of a prostitute and jumping queues were the least acceptable to all respondents, while purchasing counterfeit products was the most acceptable.

We found it surprising that two such different activities as jumping queues and engaging the services of a prostitute were rated similarly. One possible explanation is that most people have faced queue jumpers and remember the immediate and definitive negative consequence for them (a few minutes’ extra wait).

People feel jumping queues isn’t fair, not morally right and breaches established social norms.

Immanuel Kant’s deontology provides a suitable explanation for the case of prostitution. Prostitution reduces a human being to an instrument for achieving sexual climax with another person. It violates the principle of treating every person as an end in themselves rather than the means for achieving one’s objectives.

Interestingly, selling counterfeit products is illegal in many countries, including Hong Kong, but purchasing them was considered the most acceptable. There are positive consequences of purchasing counterfeit products for the purchasers (lower cost) and also for the producers and sellers (profit).

It also appears acceptable in Hong Kong as the practice is widespread. Those who purchase counterfeit goods are unlikely to feel guilty about the lost profits of luxury brands.

Cultural influences

Our findings also support the idea that morality varies from culture to culture. There are differences between the two groups of visitors we surveyed and the Hong Kong residents.

In comparison to Western tourists, mainland Chinese tourists think it’s more acceptable to purchase counterfeit products in Hong Kong, jump queues and lie about a child’s age to get discounts. Western tourists, on the other hand, find it relatively more acceptable to engage the services of a prostitute.

Both groups think public misbehaviour due to drunkenness is more acceptable than the Hong Kongers do. Overall, Hong Kong residents appear stricter in their morals than either group of tourists.

Western tourists were more likely to participate in all the scenarios on holidays than at home, except for drunken misbehaviour; they do that at home as well. Hong Kong residents are also more likely to engage in all activities on holidays than at home.

On the contrary, mainland Chinese visitors are more likely to engage in most of the scenarios at home than on holidays, engaging the services of a prostitute being the exception. It appears that Chinese tourists are aware of the bad publicity they have been getting recently , especially in Hong Kong.

The Chinese government has been distributing educational information and started to blacklist “uncivilised” tourists since 2015. Its aim is to minimise inappropriate behaviour overseas.

Chinese tourists are now more likely to behave more ethically to avoid being blacklisted and ensure their personal safety.

Moral of the story

What action we think is ethical appears to largely depend on the culture we are brought up in and live in. In other words, we do what we think is acceptable to people we know and in the place where we are.

Individual principles, inherent morality and perception of fairness may appear as stricter guides for what is morally acceptable. But appealing to the consequences and the risk of punishment seems more likely to deter people from engaging in morally dubious activities.

The idea that people are more likely to behave badly on holidays than at home, as some societal pressures are removed, appears plausible. But the case of Chinese tourists demonstrates that’s not always true.

Both punishing and educating tourists may be the best strategies for reducing unethical behaviour.

- Prostitution

- Immanuel Kant

- counterfeit goods

- Global perspectives

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Data and Reporting Analyst

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Spatiotemporal behavior pattern differentiation and preference identification of tourists from the perspective of ecotourism destination based on the tourism digital footprint data

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Environmental Design, School of Art and Media, Xi’an Technological University, Xi’an, China

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Planning and Construction Research Institute, Northwest Branch of Beijing Tsinghua Tongheng Urban Planning & Design Institute, Beijing, China

Roles Formal analysis, Validation

Roles Validation

Roles Project administration, Supervision, Validation

Affiliation Department of Product Design, School of Art and Media, Xi’an Technological University, Xi’an, China

- Wei Dong,

- Qi Kang,

- Guangkui Wang,

- Bin Zhang,

- Published: April 28, 2023

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285192

- Reader Comments

Tourist impact management in ecotourism destinations requires an accurate description of tourists’ spatiotemporal behavior patterns and recreation preferences to minimize the ecological environmental impact and maximize the recreation experience. This study classified tourist behaviors into five typical behavior patterns based on the digital footprints of tourists visiting Ziwuyu of the Qinling Mountains, including 348 traveling tracks and 750 corresponding geotagged photographs: short-distance, traversing, reentrant, large loop, and small loop. Furthermore, each behavior pattern’s recreation preference was identified using photograph analysis. Tourists with large-loop and reentrant behavior patterns have 89.8% and 30% chances of visiting Jianshanding, respectively. Key protected areas are faced with the risk of ecological environmental damage. Based on the behavior pattern differentiation and preference of tourists, this paper provides a decision-making basis for the classified management and guidance of tourists in ecotourism destinations. It has reference value for the management of similar ecotourism destinations.

Citation: Dong W, Kang Q, Wang G, Zhang B, Liu P (2023) Spatiotemporal behavior pattern differentiation and preference identification of tourists from the perspective of ecotourism destination based on the tourism digital footprint data. PLoS ONE 18(4): e0285192. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285192

Editor: Weili Duan, University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, CHINA

Received: August 25, 2022; Accepted: April 18, 2023; Published: April 28, 2023

Copyright: © 2023 Dong et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The use of the dataset was done in compliance to the Foooooot and 2bulu Privacy Policy ( https://www.2bulu.com/about/terms_use.htm , https://image1-oss.v.lvye.com/cert/app-sixfoot-yonghuxieyi.html ), which stated that the anonymized and aggregated data could be used for other services. This study was carried out with the support of Foooooot and 2bulu, and the use of anonymized and aggregated data is authorized by Foooooot and 2bulu and its Terms and Conditions. In addition, the use of third-party data is also in compliance with the Plos one policies. However, some restrictions will apply when accessing the original data, and the data request should be addressed to Foooooot ( http://www.foooooot.com/ , E-mail: [email protected] ) and 2bulu ( https://www.2bulu.com/ , Email: [email protected] ).

Funding: This paper was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (grant number 21BXW017); the Scientific Research Program Funded by Shaanxi Provincial Education Department (grant number 20JK0192) and the Humanities and Social Science Project of Education Ministry (grant number 21YJA760064). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

In the premise of “protecting natural resources of national parks, ecotourism destinations are committed to provide high-quality ecotourism services for tourists [ 1 ]. The key is to achieve a balance between human recreational activities and nature conservation [ 2 ]. Global continental ecotourism destinations witness approximately 8 billion tourist arrivals each year [ 3 ] (estimated in 2015), with an economic output of 6 trillion dollars [ 4 ] (estimated in 2019). Tourism activities in ecotourism destinations that are designed with the environment as the main attraction play an important role. However, frequent recreational activities have invariably had a negative impact on the ecological environment, such as plant trampling, a decrease in soil organic substances, the destruction of aquatic ecosystems, and the loss of wildlife habitat [ 5 , 6 ]. Therefore, effective tourist management is crucial for avoiding ecological risks, improving the recreation experience, and achieving the sustainable development of ecotourism [ 7 ].

Tourist impact management effectively solves the conflicting aims of tourism and environmental protection in ecotourism destinations [ 8 ]. The objective of tourist impact management is to achieve a dynamic balance between minimizing impact on resources and the environment and maximizing recreation experience quality at ecotourism destinations [ 9 ]. Limits of acceptable change (LAC), recreational opportunity spectrum (ROS), visitor activities management planning (VAMP), tourism optimization management model (TOMM), visitor experience and resource protection (VERP), visitor use management (VIM), and other modes of tourist impact management are currently in use [ 8 ]. Except for differences in specific operations, they have the same core idea: paying attention to the recreation experience quality of tourists and emphasizing the control of tourist impact while meeting the expectations of tourists. More flexible management measures shall be implemented according to the recreational process and characteristics of tourists [ 1 , 9 ]. Under the guidance of the aforementioned theories, studies have been conducted on tourists’ spatiotemporal behaviors with the goal of tourist impact management. These studies aimed to help identify tour routes, tour locations, and usage levels in key protected areas to provide “early warnings” of ecological risks in ecotourism destinations to minimize the impact of tourism activities on the ecological environment [ 10 ].

Most studies on tourist spatiotemporal behavior patterns in ecotourism destinations have mainly focused on the general description of the level of recreational use [ 11 ] but lack an in-depth analysis of the spatiotemporal behavior patterns of tourists and the characteristics of nonspatial tourists [ 12 ]. In particular, few studies have been conducted on tourist behavior patterns and their recreation preferences from the perspective of tourist impact management [ 13 ]. Stamberger L et al. demonstrated in a study on Denali National Park and Preserve that tourists exhibit different behavior patterns in recreational activities at ecotourism destinations, and identifying areas that may suffer environmental degradation under different patterns is critical to ensuring the effectiveness of tourist impact management [ 14 ]. Furthermore, a recent study by Väisänen T et al. found significant differences in recreation preferences among different tourist groups using geotagged photographs, emphasizing the importance of understanding tourist preferences in ecotourism destinations [ 15 ]. Given the above, it is unscientific and usually ineffective to guide tourist impact management with the research results not considering tourists’s behavior patterns and recreation preferences, which has been agreed by scholars such as Beeco JA et al. [ 1 ], Sisneros-Kidd AM et al. [ 16 ], and Wilkins EJ et al. [ 17 ].

The research objectives of this study are listed as follows: (1) guided by tourist impact management and based on the spatiotemporal factors such as visiting duration, route length, and visits to scenic spots, the typical spatiotemporal behavior patterns of tourists in ecotourism destinations were identified. The negative impacts of each pattern on key ecological reserves were evaluated. (2) Tourist recreation preferences were investigated under various patterns. Based on this, the recreation experience of tourists in each pattern was specifically optimized. Furthermore, alternative schemes for tourists entering key ecological reserves based on their recreation preferences were established, and guidance was provided through design strategies to achieve more scientific, effective, and humanized tourist impact management.

This paper is organized as follows: in the first section, the research progress of current tourist spatiotemporal behaviors is summarized from the aspects of data, methods, and applications. In the second section, the current situation of ecotourism in Ziwuyu, which is the research object, the acquisition and processing of tourists’ digital footprints, and the methods used in this study for identifying tourists’ behavior patterns and recreation preferences are discussed. The empirical research is presented in the third section, focusing on the differentiation of spatiotemporal behavior patterns of tourists in Ziwuyu; additionally, the differences in recreation preferences among different behavior patterns are detailed. This study’s summary, recommendations, discussion, and prospects are presented in the final section.

Research progress of tourists’ spatiotemporal behaviors

Digital footprints enabling the accurate description of tourists’ spatiotemporal behaviors.

After nearly half a century of development, the time-geography-centered research on spatiotemporal behaviors has become an important perspective for understanding the correlation between geographical space and human behaviors [ 18 ]. The development of surveys on spatiotemporal behaviors can be divided into four stages. The first stage mainly involved on-field behavioral observations and interviews to acquire information on the general behavior of tourists through careful observations. However, interviews are time-consuming, laborious, and limited in sample size and thus pose the risk of over-interpretation even though they can provide a deeper understanding [ 19 ]. The second stage involved using activity logs data to summarize the general spatiotemporal patterns of tourists. Mings RC, the representative scholar, summarized four typical behavior patterns through activity routes based on the activity logs of 600 tourists [ 20 ]. However, due to the over-reliance on memories and cognitive level of the respondents, surveys based on activity logs yield poor accuracy in the aspects of routes, behavior chain, and duration of stay [ 21 , 22 ].

With the development of GPS technology, positioning navigation, and timing function enabled high-accuracy and continuous information of location, speed, and time, enabling the accurate acquisition of the spatial position and state of tourists. The survey of tourists’ spatiotemporal behavior henceforth entered the third stage of development. Using GPS track data, Beeco JA et al. identified the potential recreation conflict areas of different tourist groups in urban parks [ 23 ]. Korpilo S et al. also used GPS track data to study the impact of the environment on tourist’ tour routes in complex road networks [ 24 ]. Taking ski tourism in Tatra National Park as an example, Bielański M et al. systematically explained how to use GPS track data to monitor tourist activities’ location, intensity, and duration in fragile environments [ 25 ]. Based on the GPS track data and questionnaire information of tourists in Hong Kong Ocean Park, Huang X et al. accurately described three types of spatiotemporal behavior patterns of tourists visiting Hong Kong [ 26 ]. The track data obtained using portable GPS devices have been widely used in tourist spatiotemporal behavior studies.

However, the self-collection of GPS track data is time-consuming and labor-intensive, and samples are usually limited to a specific season. Furthermore, tourists are more likely to change their routes consciously if they are aware that their spatiotemporal behaviors are being monitored. Tourists can leave electronic footprints along with positioning information on the network while traveling in the information age. Such digital footprints can paint a complex picture of tourists’ individual and group behaviors [ 27 ]. The fourth stage is the research on tourists’ spatiotemporal behaviors based on their digital footprints. American scholar Girardin F proposed the concept of digital footprint [ 28 ]. Compared with traditional sociological survey methods such as spatiotemporal diaries, brain cognitive maps, observational methods, questionnaires, and interviews, the digital footprint can record and describe the spatiotemporal behaviors of tourists more accurately. Compared with GPS location trackers, digital footprint requires less effort, can yield a larger sample size, and covers the four seasons. Thus, this data source has a better representation of tourists’ spatiotemporal behaviors.

In microscale studies on digital footprints, Wood SA et al. estimated the visiting behaviors of tourists at 836 scenic spots worldwide through the geo-referenced photographs and photographers’ information from Flickr, an online social media site. They compared the results with the experience data for these scenic spots. They found that digital footprint can be a reliable representation of empirical visitation rates [ 29 ]. Väisänen T et al. analyzed photographs captured by tourists visiting Finnish national parks using computer vision methods such as semantic clustering, scene classification, and object detection. They identified the recreation preferences of different tourist groups based on the photographs in digital footprints [ 15 ]. Liu Y obtained the jogging track data of citizens in urban parks from social media to analyze the spatiotemporal behavior patterns of jogging in urban parks and demonstrated through regression analysis that designated jogging tracks and aquatic installations in parks have a positive impact on jogging [ 30 ]. The preceding studies show that geographic reference and track data can be used to quantify tourist behavior characteristics across multiple dimensions. Such digital footprints are distinguished by their timeliness, universality, and authenticity, and they play an indispensable role in the study of tourists’ spatiotemporal behaviors. They are also becoming an important means of accurately describing tourists’ behaviors. However, few studies have successfully combined photograph and track data. Therefore, solving the problem of integrating multisource data in empirical research is critical.

Synchronous development of studies on behavior patterns and recreation preferences

The research on tourists’ spatiotemporal behaviors exhibits a trend of synchronous development between studies on behavior patterns and recreation preferences. In terms of behavior patterns, based on the spatial information of stay and the sequence information of visited places, Orellana D et al. proposed two methods for aggregating tourist behavior patterns: movement suspension patterns (MSPs) and generalized sequential patterns (GSPs) [ 31 ]. By introducing the research methods of time-geography into the study on tourist behaviors, Huang X et al. verified the feasibility of using time, spatial, and activity area information as the clustering elements of tourists’ spatiotemporal behavior patterns [ 26 ]. Kidd AM et al. extracted the start and end time of travel, place, and duration of stay, and other information from GPS tracks of tourists’ vehicles for cluster analysis and divided the behavior patterns of tourists visiting the Moose-Wilson corridor of Grand Teton National Park into three types: opportunistic commuters, wildlife/scenery viewers, and hikers [ 13 ].

With respect to the study on recreation preferences, the differences in the spatiotemporal distribution of tourists with different properties in scenic spots have been studied extensively. Taking Sarawak Malaysia Total Protected Area as an example, Abdurahman AZ et al. conducted spatial and temporal analyses of the monthly average trend of local and foreign tourists. They identified the months and places witnessing the maximum visits [ 32 ]. Huang Q et al. quantized the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of recreational behaviors of backpackers with different travel modes in Beijing [ 33 ]. Furthermore, environmental factors influencing recreation preferences have been investigated to establish a link between tourist behavior and tourist destinations. For example, Van Vliet E et al. conducted an online selection experiment of virtual parks to investigate the impact of park environmental factors on tourists’ recreation preferences. They discovered that natural factors such as trees and flowers significantly impact tourists’ recreation preferences [ 34 ]. Veitch J et al. studied the environmental factors affecting the participation of older people in physical exercise and social activities in parks. They found that tree-shaded areas and quiet trails are more important to them [ 35 ].

The research on tourist behavior patterns has mainly focused on the similarity of tourist spatiotemporal behaviors. Based on this, structured classification has been conducted to improve scenic area management. The study of tourists’ recreation preferences focuses on the differences in the tourists’ spatiotemporal behaviors and the optimization of tourists’ recreation experiences by identifying different preferences. However, the common purpose of these two types of studies is to describe tourists’ behaviors in scenic area. The current study investigated the dilemma of tourist management in ecotourism destinations in combination with these two modes of thinking.

Considering the subject and object in the research on tourist spatiotemporal behaviors

The application of tourists’ spatiotemporal behavior research can be summarized into two categories: (1) focusing on the recreation experience optimization of the recreation subject and (2) focusing on scenic area management. In terms of the recreation experience optimization, Huang X et al. proposed that tourist destinations should control the tourist flow according to different patterns, reduce waiting time at venues and facilities, and provide targeted services to improve the quality of the tourist experience. To this end, they studied the spatiotemporal behavior pattern of tourists in Hong Kong Ocean Park [ 26 ]. Taking tourist groups as the research object and through the quantitative analysis of their spatiotemporal behavior characteristics, Zhao X et al. proposed measures such as improving the travel route design of the group and adding small commercial spots to improve the travel experience of tourist groups [ 36 ]. Xia JC et al. considered tourists visiting Phillip Island, Victoria, Australia, as an example, and divided the tourism market segments by identifying several important mobility patterns. This helped park managers decide when to open scenic spots and how to arrange the daily activities at scenic spots to meet the needs of tourists and improve their experience [ 37 ].

Stamberger L et al. determined the areas that might suffer from environmental degradation by studying the spatiotemporal behavior patterns of tourists in remote areas for the research on tourists’ spatiotemporal behaviors to support scenic area management, using Denali National Park and Preserve as an example. They demonstrated the practical significance of studying tourists’ spatiotemporal behaviors in ecotourism destinations for tourist impact management [ 14 ]. To minimize the impact of tourists on the ecological environment, Kidd AM et al. analyzed the spatial behavior patterns of tourists traveling by bus in Grand Teton National Park and analyzed the classified benchmark management of tourists in ecotourism destinations [ 13 ]. D’Antonio A et al. used GPS tracking to study the spatial behavior of tourists in three parks. It was reported that understanding the spatiotemporal behavior characteristics of tourists is of great significance for protecting ecological environments such as national parks and improving the tourist experience [ 38 ].

From the above discussions, it is obvious that the application of tourist behavior research presents a binary differentiation. Some researchers focused on studying tourist behavior to improve the recreation experience, whereas some aimed to guide the tourist management of national parks by analyzing tourists’ spatiotemporal behaviors. However, according to tourist impact management theory, good coordination between environmental protection and recreation experience is required for ecotourism destinations. Thus, this study aimed to reduce the impact of ecotourism destinations on the environment and resources while increasing the quality of the recreation experience by revealing the differentiation of tourists’ spatiotemporal behavior patterns and preferences. Additionally, Ziwuyu in the Qinling Mountains was chosen to conduct empirical research.

Behavior research design under tourist impact management

Current tourist impact management of wuziyu, qinling mountains.

The Qinling Mountains, together with the Alps in Europe and the Rocky Mountains in North America, are crowned as the “three mountains” of the world. The Qinling Mountains act as the dividing line between the north and south climate in China, constitute an important ecological safety barrier and water conservation area, and is one of the regions with the richest biodiversity in the world. The Shaanxi section of the Qinling Mountains has an average annual CO2 absorption of 146.7 million tons (statistical data collected in 2021) [ 39 ], which is significant in coping with global climate change. The Qinling Mountains are characterized by uniqueness, complexity, and ecological sensitivity. With the continuous increase in the regional population, resource development, and urbanization, the Qinling Mountains are facing increasingly severe environmental stress, and the contradiction between social development and ecological environment protection is becoming increasingly prominent. The Qinling Mountains are connected with the plains through 72 valleys. The valley’s mouth-shaped area is endowed with unique natural characteristics, rich culture and historical resources, and a complete ecosystem. As a hub connecting protected and nonprotected areas, it is also the area where the conflict between development and protection is most prominent.

Ziwuyu is an important area with heritage sites, recreational resources, and ecological buffer zones located in the transitional zone of the mountain and plain ecosystems. Ziwuyu was chosen as the research object in this study to investigate the tourist impact management of ecotourism destinations. On the one hand, Ziwuyu, a typical ecotourism destination popular with tourists, can meet various recreational needs such as being close to nature, cultural education, mountaineering expeditions, and local experiences. Ziwuyu, one of the 72 valleys of the Qinling Mountains and the birthplace of Taoism, is located in Chang’an District, Xi’an City, with 108.89 degrees east longitude and 34.03 degrees north latitude, a length of 7.44 kilometers, and an area of 17.53 km 2 . Ziwuyu is an important cultural heritage-bearing area, recreational resource gathering area, and ecological buffer zone located at the ecotone of the mountain and plain ecosystems. Therefore, conducting research on tourist impact management in ecotourism destinations with Ziwuyu as the object is appropriate. On the one hand, as a typical ecotourism destination popular with tourists, Ziwuyu has numerous cultural and historical relics, such as Jinxian Temple, Cliff Stone Carvings, and Xuandu Temple, as well as over 200 types of precious medicinal materials such as Poria cocos, Gastrodia elata, and Ganoderma lucidum. Ziwuyu, with its lush peaks, beautiful scenery, dangerous terrain, and ancient trees, can accommodate a wide range of recreational needs, including getting close to nature, cultural education, mountaineering exploration, and local experience. Ziwu Valley is 29.70 km from downtown and can be reached in one hour by car. It is the valley in the Qingling Mountains closest to downtown. Previously, it could receive 80,000 to 100,000 tourists on the weekend during peak season. n the other hand, Ziwuyu is faced with urgent ecological protection. In 2019, Xi’an Qinling Mountains Ecological and Environmental Protection Regulations (“Regulations”) were issued, and the Qinling Mountains Ecological Protection Station was set up in Ziwuyu, limiting the daily count of tourists entering the valley to no more than 3000. In addition, numerous rigid control measures were implemented. As an ecotourism destination, the contradiction between recreational activities and ecological protection in Ziwuyu has become prominent.

Ziwuyu receives tourists with different tour motivations, recreational behaviors, and local villagers. Thus, taking Ziwuyu as a research object, it is typical to study the differentiation of tourist behavior patterns and their recognition of recreational references from the perspective of tourist impact management in ecotourism destinations. The terrain in Ziwuyu is higher in the south than in the north, and the valley mouth is on the northernmost side, at an elevation of about 500 m. Jianshanding, located in the valley’s southeast corner, has an elevation of 1584 m and is a protected area as defined by the regulations. According to the requirements, measures should be implemented to prevent the entry of people who are unrelated to environmental protection. In Ziwu Valley, the terrain is high in the south and low in the north. Yukou is located on the valley’s northernmost ridge at an elevation of about 500 m. According to the local tourist impact management policy, the elevation of the peak at the southeast corner of the valley reaches 1584 m. It thus belongs to the key protection area specified in the Regulations, which primarily performs the ecological protection function. Closed measures should be implemented to limit human activities to the greatest extent possible and to prohibit the entry of personnel unrelated to environmental protection, following the requirements. Such rigid constraints can help achieve tourist impact management but will also inevitably diminish the recreation experience of tourists and villagers. However, the control of the tourist count cannot eliminate the risk of environmental damage due to the ignorance of the differentiation of tourists’ spatiotemporal behavior patterns. Therefore, this study developed a method to identify behavior differentiation and preferences to support more flexible and effective tourist management in ecotourism destinations.

Acquisition and processing of tourist digital footprints

Tourism digital footprint includes GPS tracks, location photographs, travel logs, and online reviews, with a collection time span of several years. It offers the advantages of accurate positioning, rich behavior information, low cost, and a large sample size [ 40 ], enabling better control of the heterogeneity of individual recreational behavior [ 41 ]. Its effectiveness in the study of tourists’ spatiotemporal behaviors has been verified [ 42 ]. However, the digital footprint has certain shortcomings when applied to behavioral research, such as changes in data accessibility, exclusion of non-user individuals, and insufficient user attributes [ 43 ]. Thus, its reliability should be carefully considered when using it for research [ 44 ]. These are not insurmountable obstacles. The integration of data from different platforms can help increase the representativeness of samples and enable better evaluation of the heterogeneity preference of tourists in ecotourism destinations [ 45 ]. In addition, appropriate data cleaning can improve the robustness of the study [ 10 ].

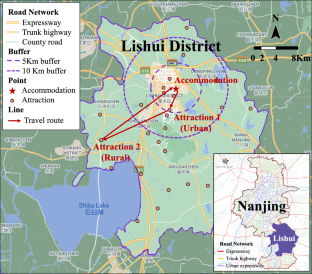

Taking the tourism digital footprints from http://www.foooooot.com/and https://www.2bulu.com/ , the two popular Internet track-sharing platforms widely used by Chinese people, as the data source. According to the privacy policies of the two platforms, users have authorized the two platforms to collect information such as personal information, activity track, and photos, as well as to use anonymized and aggregated data. Yao Q et al. and Zhang H et al. demonstrated the reliability of the two data sources in the study of tourist behavior [ 46 , 47 ]. With the support of Foooooot and 2bulu, we obtained the tourism digital footprint of Ziwuyu for March 2017-March 2020, including 482 anonymous tourist tracks and 2558 geotagged photographs ( Fig 1 ). All tourists are anonymous because this is a retrospective study of archived samples. Before we could access the data, it was completely anonymized. The ethics committee of Xi’an Technological University waived the requirement for informed consent, and the committee approved the study. A preliminary cleaning was performed on the collected track data to improve the reliability of the data for subsequent analysis. We deleted the samples that did not pass through the study area, the samples whose tracks were incomplete, and the samples wherein the positioning points were vague, and the recreational route could not be identified accurately. Furthermore, samples with a tour duration of less than 30 min and a route distance of less than 1.5 km were removed. Following cleaning, 348 effective tracks with an effective rate of 73% and 321,208 data-positioning points were obtained for analysis. Each point had the following attributes: track number, serial number, track point longitude, and latitude, the distance between two points, and timestamp. On this, the photograph data of the track were also cleaned. After deleting the samples with very low resolution, blurry images, too complex content, and unclear subjects, a total of 1792 effective photographs were obtained for the subsequent identification of the recreation preferences of tourists in Ziwuyu.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Reprinted from [ https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/data ] under a CC BY license, with permission from [United States Geological Survey], original copyright [2000]. Reprinted from [ https://www.2bulu.com/ ] under a CC BY license, with permission from [Shenzhen Bubulu Information Technology Co., Ltd.], original copyright [2020].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285192.g001

Behavioral research method based on digital footprint

Identification of tourist behavior pattern.

Touring duration and locations are the key and active variables causing environmental destruction in ecotourism destinations and are also the key attributes for identifying tourist behavior patterns. To identify the pattern differentiation, we first extracted the spatiotemporal information contained in digital footprints. A variety of behavior tracks of tourists visiting Ziwuyu were clustered into several typical behavior patterns according to their spatiotemporal attributes in the ecotourism destination. Because there were both categorical and continuous variables in the cluster elements, the TwoStep Cluster in SPSS25.0 software was used to structurally classify the recreational spatiotemporal behaviors of tourists visiting Ziwuyu. The specific steps were as follows:

Step 1: The collected track data of tourists visiting the study area were inputted into the ArcGIS software. The track was expressed as a group of continuous spatial positioning points attached with coordinates, time, elevation, and other information.

Step 2: According to theories about tourists’ spatiotemporal behaviors, the cluster elements were divided into temporal and spatial elements. The time tourists entered and exited the study area and the time spent in recreation were all considered temporal elements. The number of visits to 30 scenic spots, the number of scenic spots visited, and the length of the tour route were all spatial elements. All of these were considered to be the initial cluster elements. Some scenic spots affecting the cluster were removed according to the stops of tourists (<5%) and the significance of cluster (≥0.05).

Step 4: The nodes were classified based on the CF classification tree. The optimal cluster number was determined based on the BIC value of the Bayesian information discrimination formula and the changes in the shortest distance between clusters. Five typical spatiotemporal behavior patterns of tourists in Ziwuyu were finally obtained.

Identification of tourists’ recreation preferences

Travel photographs are an important part of tourists’ tourism activities. This study adopted photograph analysis to quantitatively analyze tourists’ recreation preferences [ 48 ]. A total of 1792 tourist photographs were classified into five groups based on cluster analysis results. The number of users in each group was not equal to the number of photographs uploaded by each user. Given the complexity of photograph content and the sensitivity of the research method, and to avoid the interference of active users on research results [ 49 ], random sampling was conducted to improve the reliability of research results. The approach was: based on the number of tourist samples of each typical behavior pattern. Given that some users had not uploaded photographs, 30 tourists were chosen randomly as the initial samples for each pattern. After that, five photographs were chosen at random from the photographs uploaded by each user for further analysis. If a user uploaded fewer than five photographs, the photographs were drawn at random from other users with the same behavior pattern based on the difference. Finally, 750 sample photographs were obtained to identify tourist recreation preferences under typical behavior patterns.

First, the 750 sample photographs were coded freely using the NVivo 10 software to interpret the content of the photographs. No more than four free nodes were selected for each photograph. Due to the various categories of free coding, the internal differences and connections among them were determined. In accordance with the content characteristics, the node categories were determined to complete the axis coding, and the differences among categories were analyzed. For instance, forests, shrubs, streams, and flowers belong to the category of the natural landscape. In contrast, temples, Taoist temples, door plaques, memorial gates, and scriptures belong to the category of historic culture. A total of four first-level codes were obtained: natural landscape, historic culture, native village, and mountaineering expedition. The frequency statistics of each free node and subtree node were exported using the statistical function of NVivo 10 to quantize tourists’ recreation preferences under different patterns. The reliability of the photograph codes was assessed after the completion of coding. In this study, 1667 nodes were coded in the first round, among which 34 nodes were modified and deleted during the second round of coding. A total of 1630 nodes were finally coded, with an agreement degree of 97%, indicating that the coding performed in this study yields high stability and reliability [ 50 ]. It is thus feasible to conduct further result analysis.

Identification of tourist spatiotemporal behavior patterns and recreation preferences

Overall characteristics of tourists’ spatiotemporal distribution.

From the overview of the sample ( Table 1 ), men accounted for 72%, of the tourists visiting Ziwuyu, much higher than that of women. The proportion of elderly, middle-aged, and young people was 76%, 16%, and 8%, respectively, indicating that elderly tourists are the main visitors to Ziwuyu. Regarding temporal distribution characteristics, 34% of tourists chose to travel in autumn, 26% in winter, 24% in spring, and 16% in summer. In terms of the tour duration, 55% of tourists toured for 4–8 h, and 34% of tourists visited for less than 4 h. Furthermore, 38 tourists visited for more than 8 h, accounting for 11% of the sample.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285192.t001

Concerning spatial distribution characteristics, 59% of tourists had a tour route of 8–16 km, 18% of tourists had a route of over 16 km, and 17% and 5% of the tourists had tour routes of 4–8 km and less than 4 km, respectively. Concerning the number of scenic spots visited, 30%, 25%, and 27% of tourists visited 5–7, 8–10, and more than ten scenic spots, respectively. Only 18% of tourists visited 2–4 scenic spots. Autumn was discovered to be the peak season for Ziwuyu, and the majority of tourists were elderly men; most of them chose a tour route of 8–16 km, with an average speed of less than 3 km/h, and visiting 5–7 nodes.

Five typical spatiotemporal behavior patterns of tourists

According to the cluster analysis results ( Table 2 ), the tourist behaviors of those visiting Ziwuyu were structured into five typical spatiotemporal behavior patterns with a proportion of 18.8%, 22.8%, 26.0%, 18.2%, and 14.2%, indicating a good cluster effect. The analysis of the clustering results from temporal and spatial characteristics revealed significant differences in the length of tour routes, number of scenic spots visited, and total number of tourist visits under the five patterns. The five spatiotemporal behavior patterns were named after the above information: short-distance, traversing, loop, large-loop, and small-loop. Each behavior pattern is explained in greater detail in the following text.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285192.t002

Pattern 1: Short-distance.

Tourists in this pattern had the shortest tour duration of approximately 3.5 h and the shortest route length of 5.8 km. As shown in the diagram of linear density analysis, such tourists were characterized by relatively dispersed tour routes and less scenic spots visited, mainly within 3 km from the entrance of the valley. The main nodes visited were the entrance, Guaierliang, and Xiliang, and the tourists left the study area from Xiliang ( Fig 2 ).

Reprinted from [ https://www.usgs.gov/centers/eros/data ] under a CC BY license, with permission from [United States Geological Survey], original copyright [2000].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285192.g002

Pattern 2: Traversing.

Tourists in this pattern had a relatively short tour duration of approximately 4 h, but the route length was 10.1 km. According to the tour route ( Fig 3 ), after entering from the entrance, tourists in this pattern passed through the nodes, including Guaierya, Jinxian Temple, Xiliang, and Qiliping, and then arrived at Tudiliang, from where the route started to disperse. They left the study area from the non-entrance.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285192.g003

Pattern 3: Reentrant.

Tourists in this pattern visited for approximately 6 h. As shown in the diagram of linear density analysis ( Fig 4 ), such tourists were characterized by relatively dispersed tour routes. The main route was to enter the mountain from the valley mouth and reach Tudiliang through Guaierya and Jinxian Temple. Due to physical constraints, it was impossible to complete the large loop; thus, tourists returned to the valley mouth using the same route or part of the same route.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285192.g004

Pattern 4: Large loop.

The duration of the tour was approximately 7.5 h, the longest tour route was approximately 17 km, and the number of scenic spots visited was up to 14. This pattern has high physical requirements for tourists. As shown in the diagram of linear density analysis ( Fig 5 ), the main route of tourists in this pattern was to start from the entrance, pass through Guaierya, Jinxian Temple, Qiliping, Shili farmhouse restaurant, Yuandengtai, Dayangjiao and Xiaoyangjiao, Jianshanding, Zuobiyuyakou, Sidaoliang, Erdaoliang, Yuandengtai, and Xiaowutai, and finally scattering into two routes to go down the mountain.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285192.g005

Pattern 5: Small loop.

According to the cluster analysis results, tourists in this pattern accounted for 18.2% of the total tourists. Tourists in this pattern had a tour duration of 6 h and 15 min and a tour length of approximately 14 km, and the number of scenic spots visited was 10. The main route was to start from the entrance, pass through Guaierya, Jinxian Temple, Qiliping, Quanzhen Temple, Zuobiyuyakou, Sidaoliang, Erdaoliang, Yuandengtai, and Xiaowutai, and return to Guaierya to leave ( Fig 6 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285192.g006

Tourists’ recreation preferences and visit probability

To further understand tourists’ recreation preferences of different behavior patterns, further investigation was conducted using photograph analysis. The results ( Table 3 ) revealed that forests, mountain roads, temples, and farmhouses, respectively, accounted for the largest shares in the four subtree nodes. According to the findings, tourists who are interested in natural landscapes are more likely to visit forests to take photographs. Tourists interested in mountaineering expeditions paid special attention to the rugged mountain roads. Temples and farmhouses drew the most attention from tourists interested in experiencing historic culture and native villages, respectively. Among the four first-level codes, natural landscape witnessed the maximum number of visits (57.55%), followed by mountaineering expeditions (25.46%) historic culture (11.60%), and native villages (5.40%). The statistical results revealed that tourists visiting Ziwuyu were mainly passionate about natural landscapes and mountaineering expeditions, supplemented by the experience of historic cultures and native villages.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285192.t003

Theoretically, tourists visiting Ziwuyu have 15 recreation preferences, including four single and 11 mixed preferences. However, according to the actual results ( Fig 7 ), there are five types of recreation preferences of tourists visiting Ziwuyu, of which two are single preferences, namely native villages and mountaineering expeditions, two are mixed preferences of two categories, namely natural landscape–historic culture and historic culture–mountaineering expedition, and one is a mixed preference of three categories, namely natural landscape–native village–mountaineering expedition. The recreation preference of each typical spatiotemporal behavior pattern is further explained here, and the probability of tourists visiting scenic spots was calculated through cross chi-square analysis to identify the risks of recreational behavior on the ecological environment of Ziwuyu.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0285192.g007

Short-distance spatiotemporal behavior pattern: Tourists who exhibit this pattern have a strong leisurely nature. Tourists preferred "Natural landscape-historic Culture" for recreation, indicating that tourists in this pattern considered Ziwuyu a daily sightseeing and leisure destination. The probability of tourists in this pattern visiting Guaierya and Xiliang was 56.9% and 58.5%, respectively, and the probability of leaving the study area was 75.4%, as indicated by cross chi-square analysis. In addition, some tourists also visited Jinxian Temple, Xiaowutai, North Dongliang, and Yuandengtai, with a visiting probability of 41.5%, 26.2%, 13.8%, and 10.7%, respectively. In this pattern, tourists were concentrated in the north of the valley mouth, with less activity duration and small activity space, thereby having less impact on the environment.