Mon - Fri 9am - 8pm

Sat 9am - 4pm

Sun 10am - 4pm

- 0800 294 2969

- Single Trip Travel Insurance

- Annual Travel Insurance

- Cruise Travel Insurance

- Family Travel Insurance

- Staycations

- Winter Sports

- Coronavirus

- Business Travel Insurance

- School Trip Travel Insurance

- All No Upper Age Limit Travel Insurance >

- Car Insurance

- Home Insurance

- Smart Luggage

- Life Insurance

Specialist Travel Insurance with no upper age limit

- Angioplasty

- Atrial Fibrillation

- Cardiomyopathy

- High Blood Pressure

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Breast Cancer

- Skin Cancer

- Lung Cancer

- Prostate Cancer

- Crohn’s Disease

- Back Problems

- Osteoporosis

- South Africa

- All Africa Insurance >

- All Asia Insurance >

- The Dominican Republic

- All Caribbean Insurance >

- All Central America Insurance >

- All Europe Insurance >

- Puerto Rico

- All North America Insurance >

- New Zealand

- All Oceania Insurance >

- All South America Insurance >

- Get a Quote

- Airport Hotels & Parking

- Travel Money

- Travel Advice

- Working with Us

- Medical Advice Hub

- Brand Showcase

- Meet The Team

- Careers: Apprenticeship Scheme

- Amend your policy

- Your Questions Answered

- Make A Complaint

- Making a Claim

Home > Latest News > Essential Guide to Travelling with High Blood Pressure

Essential Guide to Travelling with High Blood Pressure

by Phil Day | Feb 4, 2021 | Guides | 0 comments

by Phil Day

4 February 2021

An essential guide to travelling with High Blood Pressure By Phil Day, Superintendent Pharmacist – Pharmacy2U

Blood pressure is the measurement of the pressure of the blood pressing against the walls of your arteries, as it travels away from the heart. It’s one of the 4 vital signs which are monitored by medical professionals (including body temperature, pulse rate and respiratory rate) and there can be serious implications if it’s too high (hypertension).

In this article I’m going to explore high blood pressure , how it can be managed and how to be prepared when travelling.

What is high blood pressure (hypertension)?

If you have a reading of 140/90mmHg or above, this is considered to be high blood pressure.

However if you’re 80 or older, then it’s considered to be high if it’s over 150/90mmHg.

What are the symptoms of high blood pressure?

The symptoms of high blood pressure are rarely noticeable, which means you could be living with it without knowing.

The only way to tell if you have high blood pressure is by having it measured.

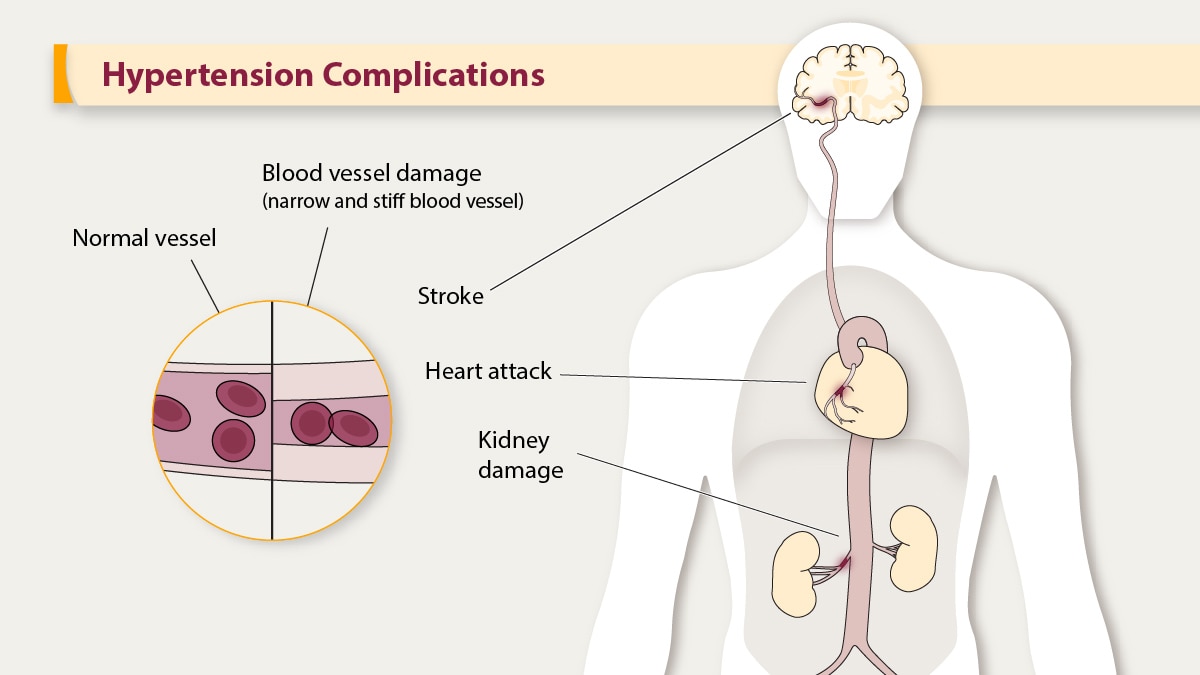

When your blood pressure is high, it puts an extra strain in your heart, blood vessels, and other organs in your body. Left untreated, it can lead to potentially life-threatening conditions such as heart disease, heart failure, strokes, kidney disease, aortic aneurysms , and others.

What causes high blood pressure?

The causes of high blood pressure are not always clear, but there are several factors that increase the risk, including:

- Not exercising enough

- Drinking too much alcohol, coffee or other caffeine-based drinks

- Eating too much salt and too few fruits and vegetables

- Not getting enough sleep, or having poor quality sleep

- Having a relative with high blood pressure

- Aged over 65

- Being of black African or black Caribbean descent

How is high blood pressure treated?

High blood pressure can usually be successfully managed , although the recommended treatment may vary from person to person.

Lowering a raised blood pressure reduces risk of developing a more serious health condition later.

By making changes to your lifestyle, it’s possible to reach and maintain a normal blood pressure.

Changes you could make include:

- Stopping smoking

- Exercising regularly

- Cutting back on alcohol

- Drinking fewer caffeinated drinks

- Losing weight, if you’re overweight

There are also medicines which can be prescribed to help keep your blood pressure under control.

Many people will need to take a combination of different medicines and the medicines you are prescribed may vary depending on age and ethnicity.

If you’re under 55 years old you’ll usually be offered or an angiotensin-2 receptor blocker (ARB), or an ACE inhibitor. If you’re 55 years old or older or of African or Caribbean origin then you’ll usually be offered a medicine called a calcium channel blocker.

It’s important to take any medicines prescribed exactly as agreed with your doctor.

When you’re taking medicine to treat high blood pressure, you will probably not feel any different – but this doesn’t mean it’s not working or that it’s not important for you to take it every day.

It’s lowering your risk of worsening health in the future.

Can I travel with high blood pressure?

Having high blood pressure shouldn’t be a barrier to travelling, but it is always a good idea to check with your GP before making any travel plans. If you’re wondering, ‘Can you fly with high blood pressure?’ the answer is yes. For those concerned about high blood pressure flying, If your high blood pressure is well controlled with medication, then flying with high blood pressure should be perfectly fine, as long as you take the right precautions. It’s important to note that there isn’t a legally imposed blood pressure limit for flying, but maintaining control over your blood pressure is crucial for safe air travel.

Tips for travelling with high blood pressure:

- Choose Travel Insurance that covers pre-existing medical conditions and make sure you declare High Blood Pressure if you have been diagnosed with it. That means it will cover any high blood pressure related medical costs if you need treatment while on holiday.

- Pack your medication in your hand luggage so that you have easy access to it and minimise the risk of your medication getting lost in your suitcase. It is a good idea to take extra medication with you just in case you lose any or end up being delayed.

- You should also take your prescription with you, as this will help in the event that you need to get more medication while you are away.

- It is best to take your own food to take on the plane with you as airline food can sometimes have high levels of salt which can increase your blood pressure levels.

- If you have a trip planned full of adrenaline-filled activities, check them with your GP just to make sure they are happy for you to take part (and mention to your Insurance provider)

- If you are travelling to a different time zone you may want to adjust the time you take your medication accordingly. However, if you want to keep taking it at the same time you do at home, for example with breakfast, this is also fine to do. Just make sure you are taking the medicine as prescribed and not taking more than the recommended dose.

How to get your high blood pressure medication from Pharmacy2U

If you have an NHS repeat prescription for high blood pressure, then Pharmacy2U can help. Our UK-based team of pharmacists can help you cut out unnecessary trips to the GP or pharmacist by delivering the medication you need to your door . Our simple service lets you order your prescription from anywhere and registration is quick and simple.

For more information and support about high blood pressure , talk to your GP or pharmacist.

Visit Pharmacy2U’s website >

Travel Insurance for High Blood Pressure

Get a quote today and ensure you declare any pre-existing medical conditions, including High Blood Pressure.

How Just Travel Cover helped me see the world…

May 15, 2024 | Blogs

We caught up with Mrs Norton, who took out her 30th policy with Just Travel Cover this year, ahead of a five week round-the-world-World Cruise....

Travellers risk ‘financial ruin’ without Travel Insurance, say ABTA

May 1, 2024 | Blogs

ABTA says big increase in medical costs abroad makes Travel Insurance even more essential. The travel association has warned travellers that ...

Travel Insurance Checklist – Everything you need to know

Mar 20, 2024 | Blogs

We know that Travel Insurance can be complex especially for those who have pre-existing medical conditions, so we have pulled together our go-to...

Compare prices in minutes

Copyright © 2023. Just Travel Cover

- Travel Tips Advice

- Compare Travel Insurance

- Pre-Existing Medical Conditions

- Holiday Home Insurance

Customer Services

- Opening Times

Victoria House, Toward Road, Sunderland, SR1 2QF

Call: 0800 294 2969

Monday - Thursday 9am - 6pm, Friday 9am - 5.30pm

Buy with Confidence

Secure Payments

UK Call Centre

Leading Broker

Justtravelcover.com is a trading style of Just Insurance Agents Limited, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) number 610022 for General Insurance Distribution activities. Registered in England. Company No 05399196, Victoria House, Toward Road, Sunderland SR1 2QF. Our services are covered by the Financial Ombudsman Service. If you cannot settle a complaint with us, eligible complainants may be entitled to refer it to the Financial Ombudsman Service for an independent assessment. The FOS Consumer Helpline is on 0800 023 4567 and their address is: Financial Ombudsman Service, Exchange Tower, London E14 9SR. Website: www.financial-ombudsman.org.uk/

Privacy Overview

Can You Fly With High Blood Pressure? What You Need To Know

Traveling is a fantastic way to escape the daily routine, experience new cultures, and create unforgettable memories. However, traveling can be challenging if you have certain health conditions, such as:

- High blood pressure

- Asthma & allergies

However, living with health conditions shouldn’t stop you from exploring the world. With adequate preparation and the right precautions, you can have a safe and enjoyable trip.

In today’s post, we’ll share everything you need to know about traveling with high blood pressure, including:

- What hypertension is

- Risks of traveling with high blood pressure

- What to consider when planning your trip

- Some tips on high blood pressure and flying

Without further ado, let’s begin.

What is Hypertension? (aka High Blood Pressure)

For most people, hypertension is defined as a blood pressure reading over 140/90 mm Hg. According to WHO, approximately 1.28 billion adults aged 30 to 79 suffer from hypertension worldwide, and 46% are unaware of it. Besides, only 1 in 5 people (21%) has it under control.

High blood pressure is a leading cause of death or a contributing factor. Sadly, hypertension doesn’t show evident symptoms.

Severe high blood pressure cases (usually 180/120 or higher) may experience the following symptoms:

- Severe headaches

- Difficulty breathing

- Blurred vision

- Abnormal heart rhythm

All in all, high blood pressure is a common condition but it can be serious if it’s not treated. Typically, you can reduce your blood pressure by adopting a healthier lifestyle with practices like:

- Exercising regularly

- Keeping a healthy diet

- Quitting smoking

- Avoiding excessive alcohol and caffeine consumption

- Monitoring blood pressure at home or your local pharmacy

- Reducing stress

- Minimizing salt consumption

Nonetheless, some people may need to take medications.

High Blood Pressure and Flying: What Are The Risks?

Overall, high blood pressure patients who take medication don’t have an increased risk of health problems at higher altitudes. Nevertheless, poorly controlled or severe hypertension does increase this risk.

The effects of occasional flying on heart health are relatively unstudied. Yet, according to a recent study , even men in good health have an increased blood pressure of 6% during commercial flights.

According to the CDC , about 1 in 600 flights experience a medical emergency, such as:

- Heart problems

- Nausea or vomiting

And blood pressure may be a contributing factor to some of these emergencies.

What to Consider When Planning Your Trip

Traveling to high altitudes (5,000 to 11,500 feet) can increase blood pressure. Why? At these heights, your blood works harder to deliver oxygen, causing blood pressure to rise.

Therefore, when planning your trip, you may want to avoid destinations like:

However, if you already booked your trip, don’t panic: managing your blood pressure at high altitudes is possible. Experts recommend:

- Light physical activity

- Avoid climbing more than 300 meters per day

Be extra mindful of these tips when staying in mountainous areas, like the Alps or the Andes.

Overall, traveling at high altitudes shouldn’t be a problem as long as your blood pressure is controlled and you take some precautions. Here are some tips you may want to consider:

- Consult your doctor 8 weeks before your trip to discuss your travel plans.

- Get your medication ready , and make sure to bring enough to cover your whole trip. Besides, bringing a bit extra may be a good idea in case your return flight gets rescheduled.

- Keep your alcohol and caffeine consumption to a minimum during your flight to avoid dehydration.

- Be careful with airline food, it might have high sodium levels , which can raise your blood pressure.

- Taking Dramamine to avoid motion sickness doesn’t interfere with blood pressure medications.

- Avoid using sedative and hypnotic medications before and during flight.

- Promote circulation by moving around during your flight with walks every two hours and by moving in your seat.

Key Takeaways

Ultimately, traveling with high blood pressure doesn’t have to limit your travel plans. With proper planning, taking necessary precautions, and consulting your doctor, you can enjoy your trip confidently and safely.

Remember to:

- Monitor your blood pressure

- Make wise choices regarding food and drink

- Stay active during your journey

Want to get tested for COVID before your next trip? No matter where you are, or what type of test you need, find testing locations near you with our international directory .

Have Travel Questions?

Join our Facebook community full of travelers like you

Recent posts

COVID Testing in San Antonio

Best Foods for COVID Recovery

COVID Testing in Spanish: What to Know and Who to Ask

COVID Pandemic Effects: Social Impact, Mental Health, Worklife, and more

Share this article.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Anatol J Cardiol

- v.25(Suppl 1); 2021

Systemic arterial hypertension and flight

Hypertension is the major preventable cause of cardiovascular disease and all-cause death. Given its overall high prevalence, hypertension would be one of our major concerns in commercial flights. Hence, the management of hypertension is of great importance. Herein, we discuss the pathophysiological factors for elevated blood pressure during flight, and we make recommendations which should be followed by the passengers and the flight crew and the physicians for trouble-free air travel.

Introduction

Conventionally, hypertension is defined as office systolic blood pressure (SBP) values ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) values ≥90 mm Hg or requiring antihypertensive medication ( 1 ). On the basis of office BP, approximately 1.13 billion people were affected by hypertension in 2015, and hypertension is the major preventable cause of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and all-cause death ( 2 ). In the PatenT2 (the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in Turkey) trial, the overall age and sex-adjusted prevalence of hypertension was found as 30.3% ( 3 ).

Approximately, 40 million people use commercial flights annually ( 4 ). It is estimated that by 2030, half of the passengers in commercial flights will be over 50 years of age because of increased life spans. At the same time, our ability to care for patients with cardiac diseases and advancement in flying technology improve continuously. Accordingly, we can predict a higher number of “older” individuals or those with cardiac diseases will travel in commercial flights ( 5 ). Given its overall prevalence mentioned above, hypertension would be one of our major concerns. The management of hypertension should be considered, both for the passengers and the flight crew.

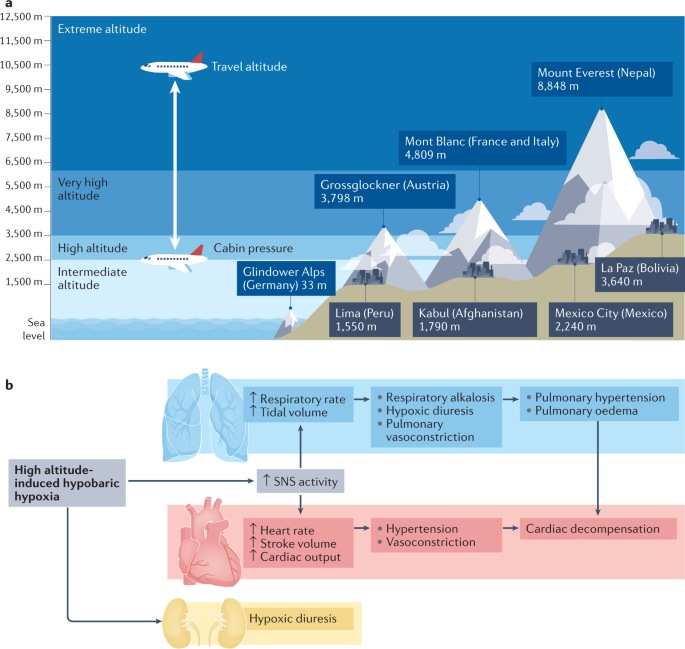

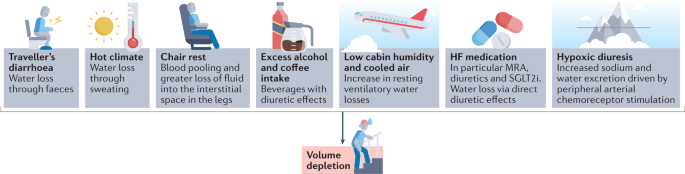

The main pathophysiological factor during a flight is altitude related decrease in oxygen saturation. Commercial airplanes fly at 30,000–40,000 feet (corresponding to 9,000–12,000 m) above the sea level. However, commercial flights maintain a relative cabin altitude between 5,000 and 8,000 feet during routine flights. However, at this altitude, the barometric pressure decreases from a normal sea level value of 760 to 560 mm Hg. This pressure change is related to the decrease in arterial oxygen tension, which is well tolerated in healthy individuals but might trigger ischemia and arrhythmia in susceptible patients. The inspired PO 2 falls by 4 mm Hg per 1,000 feet above sea level. Consequently, the patients with concomitant pulmonary diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pulmonary hypertension may require supplemental oxygen during travel. In addition, some patients with cardiovascular diseases such as severe left and/or right ventricular dysfunction and congenital heart diseases can be more sensitive to changes in arterial oxygen saturation ( 4 , 6 , 7 ). The details of acute and chronic cardiovascular changes for adaption to high altitude will not be mentioned in detail. Basically, an increase in heart rate, cardiac contractility, and cardiac output could alter systemic blood pressure. Hypoxia triggers peripheral vasodilatation and activation of the sympathetic nervous system. In patients with hypertension, however, endothelial dysfunction may inhibit hypoxic vasodilatation and even induce peripheral vasoconstriction. In healthy individuals, these mechanisms overall result in a non-significant increase of blood pressure, but with high inter-individual variability. Only a modest increase was observed in patients with controlled blood pressure ( 8 – 10 ). However, there is still a potential risk for significant elevation in systemic arterial pressure in those with uncontrolled blood pressure. Stressful factors related to flight such as increased anxiety especially during take-off and landing, changes in body position induced by acceleration and deceleration, and aircraft noise have been shown to negatively affect the mood state of the crew ( 11 ). These factors should be regarded as confounders for changes in blood pressure, both in passengers and flight crew.

Unfortunately, most data regarding changes in cardiac responses during flight were derived either from retrospective studies or small observational trials. In a recent study ( 12 ), 12 men without any known cardiac disease or coronary risk factors were monitored in commercial flights. A decrease in arterial oxygen saturation was observed during the flight when compared with baseline, with the lowest saturation recorded at 120 minutes in cruise altitude. The heart rates were similar at different times of the flight, and the maximum SBP and DBP values were recorded at the time of takeoff. The lowest SBP and DBP values were measured at cruise altitude. Oliveira-Silva et al. ( 13 ) have monitored 22 physically active men, free from pathological conditions and medications during commercial flights. They reported 24% elevated heart rate, 6% increase in blood pressure, and reduced parameters of heart rate variability.

Furthermore, important cardiovascular responses are less understood and reported during spaceflights. Norsk et al. ( 14 ) have observed male astronauts and demonstrated that weightlessness in space initially induced an increase in stroke volume and cardiac output by 35%–41% between 3 and 6 months, accompanied by unchanged or slightly reduced blood pressure by 8–10 mm Hg mainly owing to decrease in systemic vascular resistance.

Despite differences in the civil aviation authority rules among countries, some cardiovascular conditions are generally accepted to be a contraindication for air travel ( 7 , 8 , 15 , 16 ). Some examples are unstable chest pain, recent myocardial infarction, or cerebrovascular event (within the previous 2 weeks), decompensated heart failure, poorly controlled arrhythmias, uncontrolled hypertension, or pregnancy with preeclampsia. There is no cut-off blood pressure value for “uncontrolled hypertension.” However, patients with a value of greater than 180/120 mm Hg as well as those with dizziness, chest pain, confusion, severe headache, and visual problems must seek specific care. General recommendations for air travelers with hypertension are listed in Table 1 . Apart from air travelers, the flight crew, particularly pilots with elevated blood pressure. Should be evaluated and managed carefully according to the instructions from the national civil aviation authorities. Overall, pilots with well-controlled hypertension (central acting agents such as reserpine and methyldopa are prohibited) and without any end-organ damage are not suspended from flying ( 16 ).

General recommendations for air travelers with hypertension ( 7 , 8 , 16 , 17)

The number of air travelers with cardiac diseases is continuing to increase. All passengers with cardiovascular disease should take tailored advice based on their current status. High-altitude exposure is well tolerated by the hypertensive except for those with uncontrolled blood pressure levels and/or with accompanying serious cardiovascular problems. These patients must seek specific advice from their physician. General recommendations should be followed by the passengers and the flight crew for trouble-free air travel.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Guidelines for Flying With Heart Disease

Air travel is generally safe for heart patients, with appropriate precautions

- Pre-Flight Evaluation

Planning and Prevention

During your flight.

If you have heart disease, you can fly safely as a passenger on an airplane, but you need to be aware of your risks and take necessary precautions.

Heart conditions that can lead to health emergencies when flying include coronary artery disease (CAD) , cardiac arrhythmia (irregular heart rate), recent heart surgery, an implanted heart device, heart failure , and pulmonary arterial disease.

When planning air travel, anxiety about the prevention and treatment of a heart attack on a plane or worrying about questions such as "can flying cause heart attacks" may give you the jitters. You can shrink your concern about things like fear of having a heart attack after flying by planning ahead.

Air travel does not pose major risks to most people with heart disease. But there are some aspects of flying that can be problematic when you have certain heart conditions.

When you have heart disease, air flight can lead to problems due to the confined space, low oxygen concentration, dehydration, air pressure, high altitude, and the potential for increased stress. Keep in mind some of these issues compound each other's effects on your health.

Confined Space

The prolonged lack of physical movement and dehydration on an airplane may increase your risk of blood clots, including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE) . One of the biggest risks for people with heart disease who are flying is developing venous thrombosis.

These risks are higher if you have CAD or an implanted heart device, such as an artificial heart valve or a coronary stent. And if you have an arrhythmia, a blood clot in your heart can lead to a stroke.

One of the biggest risks for people with heart disease who are flying is developing an arterial blood clot or venous thrombosis.

Low Oxygen and Air Pressure

The partial pressure of oxygen is slightly lower at high altitudes than at ground level. And, while this discrepancy on an airplane is typically inconsequential, the reduced oxygen pressure in airplane cabins can lead to less-than-optimal oxygen concentration in your body if you have heart disease.

This exacerbates the effects of pre-existing heart diseases such as CAD and pulmonary hypertension .

The changes in gas pressure in an airplane cabin can translate to changes in gas volume in the body. For some people, airplane cabin pressure causes air expansion in the lungs. This can lead to serious lung or heart damage if you are recovering from recent heart surgery.

Dehydration

Dehydration due to cabin pressure at high altitude can affect your blood pressure, causing exacerbation of heart disease. This is especially problematic if you have heart failure, CAD, or an arrhythmia.

If you experience stress due to generalized anxiety about traveling or sudden turbulence on your flight, you could have an exacerbation of your hypertension or CAD.

Pre-Flight Health Evaluation

Before you fly, talk to your healthcare provider about whether you need any pre-flight tests or medication adjustments. If your heart disease is stable and well-controlled, it is considered safe for you to travel on an airplane.

But, if you're very concerned about your health due to recent symptoms, it might be better for you to confirm that it's safe with your healthcare provider first before you book a ticket that you may have to cancel.

Indications that your heart condition is unstable include:

- Heart surgery within three months

- Chest pain or a heart attack within three months

- A stroke within six months

- Uncontrolled hypertension

- Very low blood pressure

- An irregular heart rhythm that isn't controlled

If you've had a recent heart attack, a cardiologist may suggest a stress test prior to flying.

Your healthcare provider might also check your oxygen blood saturation. Heart disease with lower than 91% O2 saturation may be associated with an increased risk of flying.

Unstable heart disease is associated with a higher risk of adverse events due to flying, and you may need to avoid flying, at least temporarily, until your condition is well controlled.

People with pacemakers or implantable defibrillators can fly safely.

As you plan your flight, you need to make sure that you do so with your heart condition in mind so you can pre-emptively minimize problems.

While it's safe for you to fly with a pacemaker or defibrillator, security equipment might interfere with your device function. Ask your healthcare provider or check with the manufacturer to see if it's safe for you to go through security.

If you need to carry any liquid medications or supplemental oxygen through security, ask your healthcare provider or pharmacist for a document explaining that you need to carry it on the plane with you.

Carry a copy of your medication list, allergies, your healthcare providers' contact information, and family members' contact information in case you have a health emergency.

To avoid unnecessary anxiety, get to the airport in plenty of time to avoid stressful rushing.

As you plan your time in-flight, be sure to take the following steps:

- Request an aisle seat if you tend to need to make frequent trips to the bathroom (a common effect of congestive heart failure ) and so you can get up and walk around periodically.

- Make sure you pack all your prescriptions within reach so you won't miss any of your scheduled doses, even if there's a delay in your flight or connections.

- Consider wearing compression socks, especially on a long trip, to help prevent blood clots in your legs.

If you have been cleared by your healthcare provider to fly, rest assured that you are at very low risk of developing a problem. You can relax and do whatever you like to do on flights—snack, read, rest, or enjoy entertainment or games.

Stay hydrated and avoid excessive alcohol and caffeine, which are both dehydrating. And, if possible, get up and walk for a few minutes every two hours on a long flight, or do leg exercises, such as pumping your calves up and down, to prevent DVT.

If you develop any concerning issues while flying, let your flight attendant know right away.

People with heart disease are at higher risk for developing severe complications from COVID-19, so it's especially important for those with heart disease to wear a mask and practice social distancing while traveling.

Warning Signs

Complications can manifest with a variety of symptoms. Many of these might not turn out to be dangerous, but getting prompt medical attention can prevent serious consequences.

Symptoms to watch for:

- Lightheadedness

- Dyspnea (shortness of breath)

- Angina (chest pain)

- Palpitations (rapid heart rate)

- Tachypnea (rapid breathing)

To prepare for health emergencies, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration mandates that supplemental oxygen and an automated external defibrillator (AED) is on board for passenger airplanes that carry 30 passengers or more. Flight crews receive training in the management of in-flight medical emergencies and there are protocols in place for flight diversions if necessary.

A Word From Verywell

For most people who have heart disease , it is possible to fly safely as long as precautions are taken. Only 8% percent of medical emergencies in the air are cardiac events, but cardiac events are the most common in-flight medical cause of death.

This means that you don't need to avoid air travel if you have stable heart disease, but you do need to take precautions and be aware of warning signs so you can get prompt attention if you start to develop any trouble.

Hammadah M, Kindya BR, Allard‐Ratick MP, et al. Navigating air travel and cardiovascular concerns: Is the sky the limit? Clinical Cardiology . 2017;40(9):660-666. doi:10.1002/clc.22741.

Greenleaf JE, Rehrer NJ, Mohler SR, Quach DT, Evans DG. Airline chair-rest deconditioning: induction of immobilisation thromboemboli? . Sports Med. 2004;34(11):705-25.doi:10.2165/00007256-200434110-00002

American Heart Association. Travel and heart disease .

Ruskin KJ, Hernandez KA, Barash PG. Management of in-flight medical emergencies . Anesthesiology. 2008;108(4):749-55.doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e31816725bc

Naqvi N, Doughty VL, Starling L, et al. Hypoxic challenge testing (fitness to fly) in children with complex congenital heart disease . Heart. 2018;104(16):1333-1338.doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312753

By Richard N. Fogoros, MD Richard N. Fogoros, MD, is a retired professor of medicine and board-certified in internal medicine, clinical cardiology, and clinical electrophysiology.

Telephone Hours

Opening Hours

- Mon-Fri: 8:30am - 8pm

- Sat: 9am - 5:30pm

- Sun: 10am - 5pm

Bank Holiday Opening Hours:

- 6th May: 9am-5pm

- 27th May: 9am-5pm

- Mon-Fri: 9:00am - 8:00pm

- Sat: 9:00am - 5:30pm

- Sun: 10:00am - 5:00pm

Flying with High Blood Pressure

Can I fly with high blood pressure? Read this guide for up-to-date information and top tips for travelling with high-pressure.

Page contents

Can you fly with high blood pressure.

Millions of people fly safely with high blood pressure every year. However, there are things you should check before travelling – talk to your doctor, take your medication and travel with a blood pressure monitor – to help avoid any issues.

Before travelling with high blood pressure

Before you fly, consider visiting your doctor to discuss your travel plans – particularly if your blood pressure is unstable.

They will determine whether or not you should fly. This of course is an important consideration for your health, but also for your Travel Insurance – as you will need to be determined fit to travel for your policy to be valid.

If your doctor deems it unsafe for you to fly, they still may be able to recommend a better time for you to travel or for you to change your travel plans slightly.

Travel Insurance

You must remember to declare your high blood pressure as a pre-existing medical condition. There are many complications of high blood pressure – such as a blood clot – which you may not associate with the condition but that you won’t be covered for unless you declare high blood pressure. You’ll need cover from a specialist medical Travel Insurance provider .

Benefits of AllClear Cover

Simple 3 step quote process, 1. call us or click a quote button on our site, 2. complete our simple medical screening process, 3. get your quotes.

High blood pressure is often a condition that people don’t bother to declare, says Dr Harikrishna Patel from AllClear: “It’s often something which people get used to living with and don’t give a second thought to.”

But this is not necessarily the case: “Travelling invariably means a disruption to routine and possibly a change in time zone, so tablets may be delayed or missed altogether. Heat, physical exertion, change in diet or a tummy upset can all have an impact.

So what might be a stable medical condition at home could potentially be a problem abroad that results in a medical emergency claim.”

- If you’re taking blood pressure medication and your journey will involve you being away from home for more than a couple of weeks, make sure you have enough medication to last the duration of your trip, including extras in case of emergency.

- Consider also the time zone of your destination, as you may need to take your medication at a different time to normal.

- If you will need to take medication during your flight, be sure to speak with your airline to confirm it’s allowed in your carry-on bag.

- Bring a copy of your prescription and a letter from your doctor explaining your condition and treatment.

Blood Pressure Checker

If your blood pressure is unstable, it’s well worth investing in a good blood pressure monitor. That way you can keep an eye on your blood pressure while you’re on holiday, and ensure that it remains within a safe range.

High blood pressure is considered a level consistently at or above 140mmHg and/or 90mmHg .

Before you travel

Check the local weather and time zone of your destination and plan accordingly. Avoid travelling to places that are very hot, cold, or high in altitude, as they may affect your blood pressure.

Reduce stress

Take time to minimise the level of stress you are exposed to. This can be through simple things, like making sure you’re up to date with the latest travel updates from the FCDO before you travel or packing a few days in advance so you know you have everything you need.

You can also practice some relaxation techniques, such as deep breathing, meditation, or listening to soothing music.

During the flight

If you have high blood pressure, there are a few things you can do while flying which may help.

Eating and drinking

Stay hydrated and avoid alcohol, caffeine, and salty foods. These can dehydrate you and raise your blood pressure. Drink plenty of water and eat fresh fruits and vegetables instead.

Staying active

Walking around the plane as regularly as possible can aid circulation and reduce the risk of DVT . Gentle leg exercises from your seat can also help ensure you keep circulation moving throughout the flight. This activity helps reduce the risk of any blood clots, and you can also buy flight socks to help in this regard.

After you travel

Check your blood pressure again when you return home and compare it with your previous readings. If you notice any significant changes or symptoms, contact your doctor or seek medical attention immediately.

Resume your normal medication schedule and lifestyle as soon as possible. If you have made any adjustments to your medication or dosage while travelling, consult your doctor before changing them back. Also, try to maintain a healthy diet, exercise regularly, and manage your stress levels to keep your blood pressure under control.

The information in this blog post is not intended to replace professional medical advice. It is a general overview of a broad medical care topic. Blog posts are not tailored to one person’s specific medical requirements, diagnosis or treatment. If you do notice symptoms or you require medical advice, you should always consult your doctor or healthcare provider to obtain professional medical help. Read through our disclaimer for more information.

Written by Lydia Crispin , MA Content Creator at AllClear Edited by Letitia Smith , M.Sc. Content Manager at AllClear

Written by: Lydia Crispin | Travel Insurance Expert Last Updated: 23 August 2023

† Based on Trustpilot reviews of all companies in the Travel Insurance Company category that have over 70,000 reviews as of January 2024. AllClear Gold Plus achieved a Which? Best Buy.

Policy Wordings

Modern Slavery Statement

MaPS Travel Insurance Directory

Earn rewards by sharing with friends

Travelling with high blood pressure

- 1 Get in/Get around

- 4.1 Sodium intake

- 4.2 Sugar intake

- 4.3 Conclusion

- 7 Stay safe

Every year, millions of people with high blood pressure travel for business, leisure and family functions. People with high blood pressure deal with all the issues other travelers contend with, but also others unique to their situations. In order to have as safe, comfortable and enjoyable a trip as possible, these challenges need to be addressed.

Get in/Get around [ edit ]

If you need to travel by plane, there are special issues you must deal with if you have high blood pressure. First, you must not count on being served low-salt food on the plane, though on many flights, you might be fed a meal or snack that includes an undressed salad or crudités. But while bringing your own food onto the plane is a good idea for anyone, it's particularly important if you are on a low-salt diet. Either cook some low-salt food yourself and pack it or purchase some low-salt snack, such as fresh fruit or vegetables , hard boiled eggs or unsalted chips.

Second, many people experience ear or sinus pain, due to the change in air pressure when ascending and especially on descending. People without high blood pressure have a choice of various decongestants to use, but the most widely available decongestants all risk raising your blood pressure. However, fortunately, saline nose drops are sold in health food and drugstores, you may find them just as effective as a drug like Afrin in preventing pain from pressurization, and unless nasty additives are put into the formula (read the ingredients list), you are very unlikely to suffer any negative side effects from using them at will.

Third, everyone should get up and walk around a plane during a long flight, if possible, but this is particularly recommended for people with high blood pressure.

A fourth consideration involves where you should plan to travel, if you have the choice. This is particularly true if you also have a heart condition in addition to high blood pressure, as you may want to avoid destinations with very hot or cold weather or at high altitudes , lest you strain your heart. In addition, cold weather in particular can be dangerous for people with hypertension , so while the Wikivoyage article on cold weather can be a useful general reference, be sure to check with a trusted physician before you plan that winter vacation to the Arctic, and if you do need to get around in cold weather, bundle up appropriately and consider limiting your time outdoors.

Do [ edit ]

Depending on how well-controlled your blood pressure is and your general level of fitness, many activities may be perfectly safe and may be beneficial for you. This likely includes walking and hiking , but it is always best to check with your personal physician or cardiologist before you go, particularly if you have any doubts. Although certain kinds of exercise can increase blood pressure while you're doing them, regular exercise may lower blood pressure over time, and increasing your fitness level — carefully — is an excellent idea. If you plan to have an active trip, it's particularly important for you to attend to your fitness level with a program of exercise before you go. Exercise can mean walking, swimming or cycling and doesn't have to feel like an extremely rigorous workout (or start out as one).

Be sure to check the level of difficulty before you set out on an activity. You do not want it to come as a surprise that the last five kilometers of an otherwise easy hike are steeply uphill. Somebody not used to people with your condition might forget such "details". On guided physical activities, consider choosing a guide who understands your condition.

If you want to try activities that may put stresses on your body that it is not accustomed to, consult your doctor first. Articles here such as scuba diving , marathon race and altitude sickness have some basic information but only superficially address prior medical conditions.

Buy [ edit ]

First, make sure to buy the medications you need before you go. Should you be traveling for longer than the usual period for a refill of your prescriptions, ask your pharmacy for a vacation supply. If you are traveling for longer than they can supply you and you will be in a foreign country when you will need a refill, find out before you go what you will need to do to get more meds. In some places, a pharmacist may be able to prescribe a new supply for you without an appointment, whereas in others, you will have to make an appointment and be examined by a doctor in order to get a prescription, and it might be expensive and time-consuming to do all of this.

Second, if you have any reason to believe your blood pressure is not well-controlled, you should buy a good digital blood pressure monitor. Bring it into your doctor's office and test its readings for accuracy against the ones they get with their own professional equipment. In order to save yourself from needless worry, if your arms have a large circumference, make sure you get a monitor with an adjustable cuff that is described as being suitable for people with large arms, even though it may cost more (monitors with overly small cuffs are likely to give you inaccurately high blood pressure readings). When you travel, make sure your monitor has live batteries, and bring additional batteries with you.

Third, particularly if you are going to a country where emergency medical care and hospital stays may be very expensive and not covered by the policy that covers your health care at home, consider buying travel insurance , because you don't want to be faced with an unpayable debt of tens of thousands of dollars for a sudden heart attack or cerebral hemorrhage while on vacation. When buying travel insurance it is very important to tell the insurer about your medical condition(s); otherwise, they will send you a quote from the small print rather than money for the hospital bill. Insurance included with package holidays or bank accounts is unlikely to be sufficient.

Eat [ edit ]

Sodium intake [ edit ]

Especially if your blood pressure is not well-controlled, it may be crucial for you to eat a very low-sodium diet. A figure often mentioned as the upper limit for daily sodium intake is 2-2.4 grams — for example, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommends that "the general population consume no more than 2,300 milligrams of sodium a day", about a teaspoon of salt. But remember that sodium occurs naturally in many foods as well, so total sodium intake is more than just the amount of salt added, and some people need to limit themselves to far less than 2.3 grams of sodium per day, so be sure to get individual advice.

The best way to ensure a low-sodium diet is to know exactly what you are eating, by having and using your own cooking facilities and otherwise eating items like fresh fruit and vegetables and packaged goods that you have carefully checked for sodium amounts (yogurt is frequently a good low-sodium source of nutrition). Restaurants typically use a lot of salt, even if you cannot taste it. Restaurant-made soups, salad dressings and sauces should all be assumed by default to have a lot of salt, and you should also be very cautious about bread and other baked goods (although in Tuscany , bread is traditionally made without salt, that is seldom true anywhere else). That said, while almost no restaurants will make low-salt sauces for you from scratch, as they were already prepared hours before your meal, quite a few restaurants will work with you to provide you with low-salt items like undressed salads with no cheese or croutons, to which you can add oil and vinegar; steamed items without sauce; dishes that are sauteed or stir-fried without salt, soy sauce, salty stocks, et al.; or sometimes, baked vegetables or other baked or grilled items to which salt has not been added. However, it is quite unsafe to assume a restaurant will accommodate you if you haven't checked with them beforehand in person or by phone (etc.), especially if they are very busy and in a rush to turn over your table to the next customer.

Some cuisines are particularly difficult for people on low-salt diets. For example, in Southeast Asia , most food has shrimp paste, fish sauce or salted, dried shrimps (sometimes ground up) among the ingredients, even if you can't taste them separately. Also, beware of hot sauces, soy sauce, oyster sauce, restaurant-made stocks, and almost all varieties of cheese. And of course, not knowing the local language makes it much more difficult to communicate your health imperatives to your waiter.

Sugar intake [ edit ]

There is increasing evidence that for many people, an excess of dietary sugar may be even worse than an excess of dietary sodium and likely to raise your blood pressure by a greater amount. Keep that in mind and consider limiting or avoiding high-glycemic foods (there are many online lists showing the glycemic index and/or glycemic load of foods; here's another [dead link] ), including sweet desserts made with sucrose (table sugar), white rice, white bread and bagels, and also many processed foods you might not suspect without checking the ingredients list and nutrient panel. In certain countries such as the United States , it's also very common for all sorts of restaurants to add lots of sugar to sauces to please customers' sweet teeth.

Conclusion [ edit ]

While it may be OK for people with controlled blood pressure to eat out now and then, especially if your blood pressure remains on the high side while on medication, you are really best off cooking your own food as much as possible, if you can.

Drink [ edit ]

People with high blood pressure might consider limiting or avoiding the intake of caffeine (such as in coffee , tea , hot chocolate and colas), alcohol (see here , for example) and sugary drinks including sodas and sweet juices. In terms of alcoholic beverages, note in particular that cocktails almost all have sugar or some other sweetener as a major ingredient. However, even if you completely avoid all of these types of beverages, there are many delicious herbal teas and other types of drinks that you may find in your travels. As for the rest, consult your physician, but it's quite possible that in moderation, a bit of alcohol or tea now and then may not do you appreciable harm.

Sleep [ edit ]

If you can stay in accommodations with at least some cooking facilities and a refrigerator, it will be easier for you to control your diet.

Stay safe [ edit ]

If your blood pressure goes up to a life-threatening level (as a general reference the American Heart Association considers 180/120 a hypertensive emergency requiring immediate medical care), get to an emergency room in a hospital immediately! Also, be cautious about physical symptoms involving very high blood pressure (especially fainting, severe headache and various other kinds of persistent pains), even if your blood pressure is a bit lower than the nightmare numbers mentioned above.

Do not feel impelled to avoid all physical activity unnecessarily; double-check with your physician, but the chances are, s/he will tell you that exercise, within appropriate limits for your fitness level, is good for your health. But do try not to overexert yourself. If you feel short of breath or have other symptoms of exhaustion, stop what you are doing, sit down and relax, and if you are doing anything very strenuous that could put you in danger, make sure not to do it by yourself, so that in a pinch, another person can get help for you.

See also [ edit ]

- Dealing with emergencies

- Physical fitness

- Senior travel

- Stay healthy

- Has custom banner

- Articles with dead external links

- Topic articles

- Usable topics

- Usable articles

Navigation menu

Traveling With High Blood Pressure: Travel Tips From Cardiologist Dr. Desai

Dr. Monali Desai is a practicing cardiologist in New York and founder of IfWeWereFamily.com where she writes about health and nutrition, offering science-backed advice for living a healthier life.

High blood pressure, also known as hypertension, does not always have noticeable symptoms. But when signs do show, they can include a variety of symptoms: severe headaches, fatigue or confusion, vision problems, chest pain, and difficulty breathing.

Traveling can be stressful. If you have high blood pressure, being stressed can raise your blood pressure even further.

Many things can happen during travel that can make your blood pressure high. Stress can come from being late, experiencing delays and setbacks, and worrying about having remembered everything.

Nine tips for traveling with high blood pressure

At the airport

1. Get to the airport early. Leave yourself plenty of time to check your bag, go through security, and get to your gate early. If you’re stressed out about missing your flight, this can raise your blood pressure.

On the plane

2. Avoid eating salty snacks and drinking alcohol. This can change the salt-to-water balance in your body and increase your blood pressure. Staying well hydrated with water is also essential for the same reason.

3. Keep extra blood pressure medication in your carry-on bag in case your flight or trip is delayed or your checked bag gets lost.

4. Stay mobile on the plane. Walk in the aisles, especially on long flights. This will help prevent blood clots.

While Traveling

5. Watch out for your body’s salt-to-water ratio getting out of balance and making your blood pressure high. This can happen by eating too many salty foods, being outside in the sun, and not drinking enough water.

6. Portable blood pressure machines are relatively small and inexpensive, so take one with you.

7. Make sure you have enough blood pressure medication to last for the duration of your trip. It’s also a good idea to take at least an extra week’s worth of medication in case your trip is delayed. If you’re in your home country and you do run out, ask your doctor’s office to call in replacement medication to a local pharmacy.

8. If you’re in a foreign country, it’s a good idea to take a copy of your prescription with you, in case your medication gets lost and you need to get some more from a local chemist or doctor.

Ask your hotel for a recommendation for a local doctor or chemist who can prescribe replacement medication until you get back home.

Be aware that different countries don’t necessarily carry the same tablets you’re taking at home. If your medication does get lost or you run out, missing it for a few days can be dangerous to your health as it increases your risk of heart attack and stroke.

9. Buy travel insurance in case something happens while you’re on vacation and you need to go to the doctor. Always make sure you are properly insured before traveling. It’s important to let your insurer know if you have been diagnosed with high blood pressure too.

Monali Desai

Dr. Monali Desai is a cardiologist and a contributor for Thrive Global. She has been featured on a variety of sites including Healthline, Shape, and mindbodygreen. She writes about a wide range of topics from preventative cardiology to holistic medicine. Follow her on Instagram for more science-backed health and nutrition tips.

Hotel Review: The Beaumont in London Is An Artful Escape from the Busy City

6 of the scariest things about airports to send a shiver down your spine, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Try These 5 Tips To Prevent Lost Luggage Next Time You Travel

Gary, the Gold Coast Airport therapy dog has returned

In-flight tips during covid from a New York travel professional

Seven therapy dog programs now back at airports

Fifteen New Therapy Dog Programs Launched In The US in 2019

Useful Pages

Travelling with high blood pressure.

If your high blood pressure is under control, it should not prevent you from travelling or flying. However, you should still take precautions to maintain good health and prevent high blood pressure occurring when on holiday.

What is hypertension (high blood pressure)?

Hypertension is the medical term for high blood pressure. More than one in four adults in the UK have high blood pressure.

High blood pressure is when your blood pressure (the force of your blood pushing against the walls of your blood vessels) is consistently too high.

To find out if you have high blood pressure, visit your GP or local pharmacy to get your blood pressure checked.

What are the symptoms of high blood pressure?

High blood pressure is hard to detect and you may have it without realising. If your blood pressure is extremely high, you might experience symptoms like severe headaches, fatigue, difficulty breathing, chest pain and irregular heartbeat.

Risk of high blood pressure

High blood pressure puts pressure on your heart and other organs (brain, kidneys, eyes). If you have untreated high blood pressure you are at risk of developing serious conditions such as heart disease, kidney disease or a stroke.

Causes of high blood pressure

You are at risk of developing high pressure if you:

- are 65 or over

- are overweight (or obese)

- don't exercise

- drink excessive amounts of alcohol

- have a relative with high blood pressure

Visit your doctor regularly to check your blood pressure, especially before travelling.

Flying with high blood pressure

It is safe to fly with high blood pressure if it is well controlled. However, you may experience some discomfort during your flight such as an earache. Your blood pressure is likely to rise as well, but this is normal. If your blood pressure is unstable or very high, then you should talk to your doctor before flying.

Rises in blood pressure

Aeroplane cabins have less oxygen. Less oxygen in the blood can lead to high blood pressure.

If you already have high blood pressure, you are at a higher risk of developing heart failure, coronary artery disease, and other health conditions. This doesn't mean you can't fly, but you must take precautions to lower your risk.

Avoid salty food or drinking alcohol. If you take blood pressure medication, pack it in your carry-on so you can take it as needed.

Deep Vein Thrombosis

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) occurs when a blood clot forms in the leg. The clot can break off and move through the blood to your brain, lungs or heart (causing an embolism). Flying puts you at higher risk of developing DVT since it limits your mobility.

You can take precautions to keep your blood circulating as normal, these include wearing comfortable and loose-fitting clothing, bending and straightening your legs, massaging your calf muscles, and walking up and down the aisles.

Earache or temporary hearing loss

Why you fly, you might experience a painful earache or temporary hearing loss to due to the rapid change in altitude as the plane takes off and lands. There are some things you can do to avoid a painful earache.

Try swallowing which will cause the air pressure in your ear to equalise, chewing gum or sucking on hard boiled sweets, yawning, and drinking lots of water.

What to consider before planning your trip

Choosing a holiday destination.

If you have high blood pressure, deciding on a holiday destination may be challenging, as you may have health-related concerns to consider. Use the gov.uk website for travel advice by country.

Environment

When choosing a holiday environment, think about the symptoms and what makes these worse.

Extreme heat can cause dizziness or fainting, and risk dehydration. Hilly places require you to be physically fit and can make you breathless. Are there adequate amenities (you may take diuretics and need to use the toilet frequently).

Accommodation

Does your accommodation suit your access needs? Do you need to avoid flights of stairs or need to use a lift? Choose ground-floor accommodation. Contact your preferred accommodation to check what help will be available to you.

Altitude sickness

Travelling to high altitudes (5,000 to 11,500 feet above sea level) can raise a person’s blood pressure. At high altitudes, the blood in your body works harder to pump oxygen. This stress can cause high blood pressure.

However, if you have already booked your trip, there are ways to manage your blood pressure at high altitude. Experts recommend only light physical activity to avoid putting a strain on your heart. You should avoid climbing more than 300 meters per day when in high-altitude locations to reduce breathlessness.

If you are yet to book your trip, you should avoid countries with high altitude. Countries like:

And be especially careful if you’re staying in mountainous regions such as the Alps.

If your high blood pressure is under control, and you take some precautions, travelling at high altitudes shouldn't be a problem.

Preparing for your trip

Speak to your gp.

Visit your GP eight weeks before you travel to discuss your travel plans. Your doctor will check your blood pressure and determine if it is suitable for you to fly. If you are considered unfit to fly, your GP will advise you on how to change your travel plans to suit your needs.

Prepare your medication

If you are taking blood pressure medication and your journey will involve you being away from home for more than a couple of weeks, make sure you have enough medication to last the duration of your trip—usually enough for your holiday plus an extra week. And never put them in your checked-in luggage, if your case is lost or stolen, you’ll lose all your medication. Always store it in your carry-on.

Remember to pack your blood pressure monitor, especially if you have high blood pressure (pulmonary hypertension) or your blood pressure isn't well controlled. A blood pressure monitor ensures that your blood pressure remains within a safe range.

Travelling checklist

It may be helpful to carry the following with you in your hand luggage:

- your passport

- your EHIC card

- your insurance documents

- your prescription or a list of your medication

- a letter from your GP or specialist explaining your condition (if required)

- any tests results you think might be important (ECG record)

- a portable blood pressure monitor (if needed)

- oxygen if you suffer from pulmonary hypertension

- flight socks

- travel sickness medication

- Healthy snacks and water

High blood pressure and travel insurance

Do i need travel insurance if i have high blood pressure.

If your blood pressure is normal, but you have had high blood pressure previously, or you use medication to keep your blood pressure low, you will need to declare it as a pre-existing medical condition.

If you have complications abroad and haven't declared your condition, your claim may be invalid. It is vital that you state your pre-existing condition even if your blood levels are normal.

How to apply for travel insurance

We make it easy for people with high blood pressure to find insurance. Take our blood pressure questionnaire . Our questionnaire will ask you to enter your details and answer any questions relevant to your condition. Your answers allow us to assess your current health condition and list suitable insurance options, which means we’ll do the searching for you.

Apply for an EHIC medical card

If you’re travelling in Europe, make sure you own a European Health Insurance Card (EHIC card). The EHIC card protects you from expensive medical bills and may allow you to receive free or reduced-cost health care.

Visit our EHIC card page for details about how to apply, renew or replace an EHIC card plus a comprehensive list of countries it’s accepted in, and the circumstances it covers.

Travelling with children with high blood pressure

Children of all ages (from birth to teens) can have high blood pressure. Just like high blood pressure in adults, it's hard to spot and often goes unnoticed. Children with high blood pressure should be treated the same as adults when travelling.

If your child has a history of high blood pressure or takes medication to control it, consult your GP about your travel plans.

When not to travel with high blood pressure

As long as your blood pressure is controlled, you should be able to travel as normal. Check with your doctor if you are unsure about how fit you are to travel.

What do the different blood pressure readings mean?

- Less than 120 over 80: Your blood pressure is normal.

- Between 120 over 80 and 140 over 90: Your blood pressure is higher than normal.

- 140 over 90 or higher: You have high blood pressure. You should consult your GP.

If your blood pressure is higher than 120 over 80, seek medical advice before you travel.

Enjoy your trip!

Having high blood pressure should not stop you from enjoying a globe-trotting lifestyle. Travelling abroad, including flying, is generally fine if your high blood pressure is well controlled.

More advice

- Travel advice

- Medical condition - High Blood Pressure

Ready for your online quote?

Tired of looking around for medical travel insurance? Why not use our quick and simple quote engine?

In need of assistance?

Our medical travel insurance team are ready to provide you with assistance regarding your quote. If you would prefer to talk to an advisor to receive a quote or have a query please contact our UK based customer service team. Find out details on our contact us page .

Medical travel insurance is an online comparison website for those with pre-existing medical conditions requiring travel insurance. Medical travel insurance www.medicaltravelinsurance.co.uk is a trading style of Brokersure Ltd. Brokersure is authorised and regulated by the FCA.

For more information regarding Medical Travel Insurance click here , alternatively phone or email us.

Phone: 0330 880 3601

Email: [email protected]

- Medical Travel Insurance

- Digital House

- Threshelfords Business Park

- Inworth Road

Opening Hours

- Open Monday to Friday 8:30am to 6pm, Saturday 8:30am to 4pm and closed Sundays

Useful Links

- Get a Quote

- Policy Documents

- Terms & Conditions

- Terms Of Business

Medicaltravelinsurance.co.uk travel insurance is a trading style of Brokersure Ltd who are authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. FCA No: 501719. Brokersure Ltd, Digital House, Threshelfords Business Park, Inworth Road, Feering, Essex, CO5 9SE.

Copyright © Brokersure Ltd 2024. All rights reserved.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 06 January 2022

Travelling with heart failure: risk assessment and practical recommendations

- Stephan von Haehling 1 , 2 ,

- Christoph Birner 3 , 4 ,

- Elke Dworatzek 5 , 6 ,

- Stefan Frantz 7 ,

- Kristian Hellenkamp 1 ,

- Carsten W. Israel 8 ,

- Tibor Kempf 9 ,

- Hermann H. Klein 10 ,

- Christoph Knosalla ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8127-5019 6 , 11 , 12 ,

- Ulrich Laufs ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2620-9323 13 ,

- Philip Raake 14 , 15 ,

- Rolf Wachter 1 , 2 , 13 &

- Gerd Hasenfuss 1 , 2

Nature Reviews Cardiology volume 19 , pages 302–313 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

40k Accesses

6 Citations

165 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Heart failure

- Patient education

Patients with heart failure are at a higher risk of cardiovascular events compared with the general population, particularly during domestic or international travel. Patients with heart failure should adhere to specific recommendations during travel to lower their risk of developing heart failure symptoms. In this Review, we aim to provide clinicians with a set of guidelines for patients with heart failure embarking on national or international travel. Considerations when choosing a travel destination include travel distance and time, the season upon arrival, air pollution levels, jet lag and altitude level because all these factors can increase the risk of symptom development in patients with heart failure. In particular, volume depletion is of major concern while travelling given that it can contribute to worsening heart failure symptoms. Pre-travel risk assessment should be performed by a clinician 4–6 weeks before departure, and patients should receive advice on potential travel-related illness and on strategies to prevent volume depletion. Oxygen supplementation might be useful for patients who are very symptomatic. Upon arrival at the destination, potential drug-induced photosensitivity (particularly in tropical destinations) and risks associated with the local cuisine require consideration. Special recommendations are needed for patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices or left ventricular assist devices as well as for those who have undergone major cardiac surgery.

Patients with heart failure (HF) are recommended to schedule a specialist consultation for pre-travel risk assessment 4–6 weeks before departure.

Preparation for travel requires special considerations in patients with HF, including the choice of destination, availability of medical resources and strategies to prevent volume depletion.

Most patients with HF can travel when medically stable; patients with a ground-level oxygen saturation ≤90% or those in NYHA class III–IV might need an on-board medical oxygen supply.

All medication and important documents should be stored in carry-on luggage.

Volume depletion and dehydration are important considerations requiring meticulous attention with regards to medication adjustment and fluid intake.

Patients with implantable cardiac devices might require extra time at security checkpoints and additional documents; for some patients, remote monitoring of implantable cardiac devices might be useful.

Similar content being viewed by others

Evaluating the “holiday season effect” of hospital care on the risk of mortality from pulmonary embolism: a nationwide analysis in Taiwan

The role of cardiac rehabilitation in improving cardiovascular outcomes

Variation in community and ambulance care processes for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction.

Domestic and international travel are associated with increased health risks, with 20–70% of individuals reporting health issues during their travels 1 . During international travel, 1–5% of individuals seek medical attention and the rate of death among travellers is 1 in 100,000, with cardiovascular disease being the most frequent cause of death 1 . Trauma, particularly from motor vehicle accidents, is another major cause of death while travelling 1 . Health-care providers are frequently approached by patients for advice on how to prepare for travel or to determine whether travelling is advisable at all. General practitioners can provide information to healthy individuals but specialist consultation is of benefit for patients with underlying illnesses such heart failure (HF) 2 . Indeed, many patients with HF intend to travel for business or leisure. Although some guidance has been published 3 , a systematic overview of recommendations for patients with HF planning to travel is not yet available. In this Review, we aim to provide clinicians with recommendations for preparatory measures before travel to inform and educate patients with HF. We discuss factors that might increase the risk of HF symptom development, such as local climate, air pollution levels and altitude levels, and provide specific guidance for patients with a cardiac implantable device and those who have undergone major surgery.

Which patients with HF can travel safely?

To date, guidance on travel recommendations for patients with HF is limited. In general, patients with NYHA class I–III HF who are stable should be able to travel safely 4 . However, patients with NYHA class III HF who are planning to travel by air should be advised to consider on-board medical oxygen support. Patients with NYHA class IV should not travel; however, if travel is unavoidable, on-board oxygen and medical assistance should be requested. A patient with an oxygen saturation rate >90% at ground level usually will not require medical oxygen during flight 5 . An overview of whether travelling is advisable for different classes of HF 6 , 7 is provided in Box 1 . An overview of contraindications for air travel in patients with cardiovascular diseases is provided in Box 2 .

Box 1 Travel recommendations for patients with heart failure

Chronic stable heart failure

NYHA class I–II: travel advisable, if patient is stable

NYHA class III: travel advisable, if patient is stable; consider use of on-board medical oxygen during air travel

NYHA class IV: travel not advisable; if travel is unavoidable, on-board oyxgen and medical assistance are required

Acute heart failure decompensation

Travel not advisable until at least 6 weeks after discharge and rehabilitation, if patient is stable

Ventricular assist device implantation

Travel advisable after hospital discharge and rehabilitation, if patient is stable

Heart transplantation

Not advisable until at least 1 year after transplantation surgery, if patient is stable

Implantable cardioverter–defibrillator or cardiac resynchronization therapy implantation

Not advisable until at least 2 weeks after discharge, if patient is stable

Box 2 Contraindications for air travel in patients with cardiovascular disease

Myocardial infarction (ST-elevation or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction) within the previous 2 weeks

Unstable angina without further diagnostics and treatment

Percutaneous coronary angioplasty within the previous 2 weeks; in patients who have undergone uncomplicated percutaneous coronary intervention, shorter time frames might be acceptable

Cardiac surgery or interventional valve therapy within the previous 3 weeks

NYHA class IV heart failure or any decompensated heart failure

Untreated arrhythmias (ventricular or supraventricular)

Eisenmenger syndrome

Uncontrolled pulmonary artery hypertension

Pneumothorax (such as after major cardiac surgery)

Choice of destination

The choice of destination for travel can have important health implications for patients with HF, particularly when travelling abroad. Considerations include the local climate, air pollution levels, altitude levels, the season upon arrival, the distance and time for travelling, jet lag, and vaccines required.

Effects of transitioning climates on HF

Individuals who transition through climates different to the one they reside in (such as someone living in the arctic travelling to a tropical island) are at an increased health risk. In general, people living in warmer regions tend to be most vulnerable to cold weather and, conversely, those residing in a cold climate are most sensitive to heat 8 . Exposure to extreme heat has been associated with increased morbidity and mortality from heat exhaustion and heat stroke 9 , 10 . Maintenance of homeostasis during hot weather requires an increase in cardiac output; heat tolerance is impaired when cardiac output cannot be increased to meet the requirements of heat loss. Numerous medications that are frequently prescribed for individuals with HF can also increase susceptibility to heat stroke, including loop diuretics, serotonic antidepressants, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and proton-pump inhibitors 11 , 12 , 13 . Colder temperatures are less likely to have effects on cardiovascular health but have been associated with increased morbidity among patients with respiratory disease 14 . Patients with HF should be advised to choose either spring or autumn for international travel to avoid travelling during extremities in weather and to adjust medications that can contribute to volume depletion. Appropriate clothing is required for the site of departure, the destination and for the journey itself. Given the challenges in contacting a patient’s primary care physician if the patient is in a different country or continent, distant travel destinations might only be advisable for patients who are well-informed about their medication regimen, dietary restrictions and exercise limitations.

Endemic diseases

The need for immunization for travel depends on the destination. In general, the status of routine vaccinations, such as the diphtheria, measles–mumps–rubella, pertussis, tetanus and varicella vaccines, should be checked before travelling abroad. For all patients with HF, vaccines are required for pneumococcal disease, influenza and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Other destination-dependent vaccines are provided in Table 1 .

Air pollution and HF

Air pollution can be measured by the air quality index, which integrates measures for the five main air pollutants: ground-level ozone, particulate matter, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide and nitrogen dioxide. An air quality index value of 0–50 indicates good air quality, 51–100 indicates moderately polluted air, >100 indicates an unhealthy level of air pollution and >300 designates a hazardous environment 15 . Particulate matter (PM) of ≤10 µm (PM 10 ) or ≤2.5 µm (PM 2.5 ) in diameter are linked with increased cardiopulmonary mortality 16 , 17 as well as with an increased risk of hospitalization for HF 18 and death 19 . The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying this increased risk remain elusive. Accumulating evidence points towards a crucial role of PM-induced systemic oxidative stress 20 and endothelial dysfunction 21 in the development of arterial vasoconstriction and elevated systemic blood pressure 22 . In addition, PM-induced pulmonary vasoconstriction results from increases in pulmonary and right ventricular diastolic filling pressures, which affect right ventricular performance 22 . Given that the effects of air pollutants on cardiovascular performance and outcomes can occur within hours or days of exposure 23 , patients with HF should be advised to avoid travelling to locations with high levels of air pollution.

Altitude-induced hypoxia and HF