Stephen King Wiki

Hello Stephen King fan ! We at the Stephen King Wiki are incredibly happy you've decided to visit, please feel free to check out our Discusions and/or start editing articles. If you're visiting anonymously you'll need to make an account . Before you start editing or posting, you'll want to read our simple ruleset , just so you don't accidentally break any rules. If you see anyone breaking any of these rules, please report it to the message wall of an Administrator .

Captain Trips

- View history

Captain Trips is a nickname for the constantly-shifting antigen virus that exterminates 99.4% of the human population in The Stand . The meaning of the nickname is never revealed.

- 1 Background

- 2 Description & Symptoms

- 3 Susceptibility

- 6 Aftermath

- 7 Appearances

Background [ ]

Developed under the codename Project Blue by a biological weapon's laboratory located beneath California's Mojave Desert, it is also known as Blue virus ( Blue Virus ), 848-AB , A-prime , A6 , the rales , superflu , choking sickness , and tube neck .

The virus is set loose on the population when Charlie Campion , who was working in the base that developed it, noticed that the virus had been released throughout the facility and managed to escape with his wife and daughter, but not before being infected with it himself. He carried the virus all the way to Arnette, Texas , before dying, thus setting in motion the events of the novel.

Description & Symptoms [ ]

Captain Trips is an extremely deadly virus, able to be transmitted as easily as the common flu it is based on, with far more lethal results. It has a communicability rate of 99.4%, meaning that all but a tiny number of humans can catch it. The virus starts out like a common cold, causing weariness, nasal congestion and sneezing, and most people who catch it think that a common cold is all they have.

The superflu virus is highly adaptable, shifting and changing constantly, making medicines useless against it. At best, medicine only briefly holds off the inevitable. No vaccine was ever developed for it, before or after its escape from the lab where it was created, as its constantly-changing nature made a vaccine impossible to create. The fact that it was designed as a biological weapon is another reason for the lack of a cure; it was supposed to be unstoppable, as anything less would have limited its ability to kill swiftly and efficiently.

As it progresses, Captain Trips causes increasingly-worse fever, headaches, crippling physical pain, swelling, and delirium. Victims slip in and out of consciousness, and begin thinking they are in other places, other times in their lives. Sometimes, when nearing death, victims will actually calm down and return to clear, level-headed thinking for a short time. In all cases, however, once someone has caught Captain Trips, the chances of death are 100% certain - it's just a question of how long it will take for the virus and it's complications to wear out their body's natural defenses.

Susceptibility [ ]

- Domestic guinea pigs ( Cavia porcellus )

Immunity [ ]

It is unknown how a given human or animal can be immune to the superflu, but based on the United States Military's own knowledge of the virus (from data on it in the files of Project Blue), 0.6% of the human race was immune to it. Most likely, immunity is genetic, and would be that way for the animals capable of catching the virus as well.

Colonel Richard Deitz, operating in Atlanta, then in Vermont after the Plague Center in Atlanta was compromised, led the effort to find a cure for the virus. Due to the fact that "Captain Trips" shifts at an extremely rapid pace, not one attempted vaccine worked. Men and women with a lifetime of experience in medicine were mystified at Stuart Redman's survival, especially after they injected him with the superflu under the guise of administering a sedative. Redman's immune system swiftly isolated and killed the virus, but with no visible sign of how.

Human civilization collapsed entirely within one month of the outbreak, and no cure or means of giving others immunity to the superflu was ever developed.

Outbreak [ ]

The superflu was a biological weapon created by the American government, which got loose during a containment breach on June 13, 1990. Everyone died in the base, except for a security guard named Charlie Campion, who fled the base with his wife and child, unaware that he was infected himself.

Campion was able to survive long enough to drive to a gas station in Arnette, Texas on June 16, before succumbing to the virus. The virus spread to the residents of Arnette, and on June 18, started an explosive spread across America and then the world, like a chain letter from Hell. It had a 99.4% communicability rate and a 99% mortality rate. The US government forced news services to print and broadcast the official line, which was that there was nothing wrong going on, it was just the normal flu, and the situation was being under control.

Hospitals were soon over-filled to capacity and entire towns were quarantined as soldiers were deployed on the roads and highways, blocking off the entrances and exits. It wasn't long before evidence to the contrary began to spread: photos, videos, and eyewitness accounts revealed to the world the truth. Film footage of soldiers coldly dumping bodies into harbors from trucks and barge-trains full of plague victims that were towed out to the sea to be dumped was seen by protestors and shown on the news. US military operations were soon directed toward news networks that broadcast the footage, many of them being shut down by violent means.

Posters went up on college and university campuses throughout the country. Flyers that were variations on the theme of government complicity and cover-up with the superflu, which spread panic. Rebellious journalists, news staff, and talk radio broadcasters began to print and broadcast the truth, alerting the public to the lethal pandemic and the government coverup. To suppress the news, soldiers massacred protesting college students, executed news employees, and blew up the buildings of news broadcasters.

Full blown riots broke out in most parts of the country (and the world), as people took advantage of the situation to loot for supplies. Eventually, these looters and rioters caught the superflu, and either locked themselves in other peoples’ houses, or died trying to leave the city in clogged highways. Most of the population died either bedridden in their own homes, or stuck in traffic until they succumbed to the plague. The president, himself infected with the superflu, gave one last speech to a dying country, one last time denying its lethality and that the virus was created by the government.

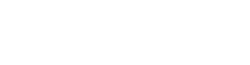

Eventually, the superflu burned out, and by July 4, 1990, 99.4% of the human population had died. Bodies laid either in their own homes, in their cars, or even on the streets.

Aftermath [ ]

Captain Trips, a man-made virus created by the United States Military on taxpayer dollars, killed all but a handful of the humans, dogs, guinea pigs, horses and monkeys on Earth by July 4 of 1980/1985/1990/1994/2020 (depending on the exact version or adaptation of the story). Riots, suicides, accidents, injuries (many of which were made fatal by a total absence of functioning hospitals and available living medical personnel), and murders cut down the number of survivors even further.

The animal species able to catch Captain Trips are implied to be doomed, left without a sustainable population, and humans have an uncertain future at best. While Frannie Goldsmith's baby, Peter, was able to fight off the superflu, another woman in Boulder had previously given birth to twins, and both of them had caught the superflu and died.

Millions of dead bodies were left in the wake of Captain Trips, most killed by the virus, others from different causes. In the few areas where survivors congregated, like Las Vegas, Nevada and Boulder, Colorado in the former United States, the decaying remains were collected and buried in mass graves. Everywhere else, the bodies were left in the hospitals, houses, cars, and on the streets where they had died. With the human population virtually wiped out, nearly all of the old world's settlements, vehicles, structures and buildings were abandoned, left to be reclaimed by the elements.

Appearances [ ]

- The Stand: The Complete & Uncut Edition

- Wizard and Glass

- The Stand: Captain Trips

- The Stand: American Nightmares

- The Stand: Soul Survivors

- The Stand (miniseries)

- The Stand (2020 Miniseries)

Gallery [ ]

- Stephen King

- 2 Beverly Marsh

- 3 Eddie Kaspbrak

Screen Rant

The stand: where the superflu nickname "captain trips" comes from.

Stephen King's The Stand features a deadly virus that spreads across the United States that is often called "Captain Trips," but what does it mean?

Stephen King's The Stand features a deadly virus that sweeps across the United States, killing over 99% of the population. In the book, the virus is most often called the superflu, but it goes by several other names as well, including an odd one, Captain Trips. Here's where this curious nickname likely stems from.

The Superflu in The Stand goes by many names. The scientists working in the weapons lab where the virus originated call it by its military codename, " Project Blue ." However, it's also called " A-Prime ," " A6 ," and " 848-AB " at various points in the novel. Outside of the military and scientific community in the thick of the superflu pandemic , it goes by different names that are far more descriptive. It's called "choking sickness," "the rales," "tube neck," and, of course, the "superflu." Given the fact that the virus is a respiratory illness, many of these colloquial terms are rather fitting and self-explanatory.

Related: The Stand: How The Superflu Started In Each Version (Miniseries & Book)

However, the name "Captain Trips" is a bit harder to describe. Stephen King has never officially explained why the Superflu is called Captain Trips, other than it's a term young people came up with to identify the virus. Given that and nothing else, the term Captain Trips likely refers to the symptoms of the virus in that it causes delirium, some rather hungover-like headaches, and hallucinations similar to those experienced by people on LSD. On the other hand, the term goes deeper than that and may even refer to legendary rocker Jerry Garcia from the Grateful Dead.

Other Theories About The Stand's Term "Captain Trips"

In addition to the term "Captain Trips" never being explained in Stephen King's book , it also never comes up in any of the adaptations. The Stand has been published in two different versions, made into a comic book series, and twice been developed into a miniseries for television. In each one, the virus is referred to as Captain Trips on several occasions. It even appears in King's short story " Night Surf ," that was published in 1969 and served as inspiration for the larger epic. In the 2020 miniseries version of The Stand (made for CBS All Access), the term Captain Trips is used in the first episode.

Perhaps one of the most likely origins of the term Captain Trips is a reference to Grateful Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia. In his day, Garcia had the nickname "Captain Trips" because he was known for spiking people's drinks with hallucinogenic drugs, particularly LSD. It could also have originated with one of the pioneers of LSD, Alfred Mathew Hubbard, who has been called " The Original Captain Trips ." The theory is that contracting the superflu virus is a lot like unknowingly dropping acid and falling into a deep delirium.

One final explanation is that the term is referencing the fact that the superflu virus was developed for military purposes and that human incompetence allowed it to spread. In other words, the US army creates the virus and then a captain holding a jar of it literally trips and drops the jar, where it smashes open and brings about the end of the world. That said, it's still possible that The Stand on CBS All Access could solve this mystery once and for all, although perhaps it's better for the explanation to be left to the imagination.

Next: The Stand's Shining Easter Egg Hints At A Stephen King Universe Connection

‘The Stand’ Episode 1 ‘The End’ Spoilers: Why are Stu, Harold and Frannie not infected with Captain Trips virus?

Spoilers for ‘The Stand’ on CBS All Access and Stephen King's 1978 novel

Aptly named ‘The End’, the first episode of ‘The Stand’ spills death and doom. The one-hour dark fantasy episode begins with a prologue by Randall Flagg aka The Dark Man (Alexander Skarsgård). “The Dark Man grows stronger... He comes to destroy all who stand against him,” he says and the scene shifts to a room full of dead men crammed inside with insects buzzing around.

Based on Stephen King's book, the nine-episodic miniseries introduces a deadly virus (dubbed “Captain Trips”) that almost wipes out the population of the world. Mysteriously, Stuart Redman (James Marsden), Frances Goldsmith (Odessa Young) and Harold Lauder (Owen Teague) are among the few who aren't affected by contagious influenza. Right in the beginning, Stu is told, “The reason why I'm not wearing a mask is because you are not contagious.” Later in the episode, Harold tells Frannie after saving her from an attempted suicide, “Frannie we are the only ones remaining... That means the fatality rate for this virus is 99 percent. That means we're the future.”

The mind-boggling twist will leave one question buzzing through your mind if you haven't read King's novel: Why are Stu, Frannie and Harold not infected with Captain Trips? Ready for spoilers from the book? Well, read at your own risk.

In ‘The Stand’ — ‘Chapter 14’, Four stages of Captain Trips — a man-made virus that is later revealed to have been created by the United States Military on taxpayer dollars — varies from person to person but is highly contagious in all its stages:

STAGE ONE : No visible symptoms. However, a person may experience abnormal fluctuations in blood pressure and the appearance of “wagon wheel” incubator cells. In the book, Bob Brentwood and Eva Hodges go through the first stage.

STAGE TWO : Headache, sniffles, sneezes, mild cough are some symptoms and you may not be able to identify if differs from the flu. Although most characters, like Norm Bruett, are able to continue normal activities, but it slowly starts to affect their health with swelling in lymph glands.

STAGE THREE : With intense respiratory symptoms, painful swollen glands, high fever, it leads to a combination of mononucleosis and influenza (grading to pneumonia). Characters like Alice Underwood undergo the stage before going to bed or seeking medical help. STAGE FOUR : The tube neck is the most common symptom and it leads to pneumonic plague and cancer. As shown in the CBS All Access series, it leads to a buildup of phlegm and blood with a high fever. In the book, characters like Charles Campion and Christopher Bradenton are depicted facing these troubles before their fatal end.

But, how do the survivors remain unaffected by the virus?

As per a Fandom bio, there's no specific reason why certain people are immune to the superflu, but the date of Project Blue files in the book attributed it to genes. The description reads: “Colonel Richard Deitz, operating in Atlanta, then in Vermont after the Plague Center in Atlanta was compromised, led the effort to find a cure for the virus. Due to the fact that Captain Trips shifts and changes at an extremely rapid pace, not one attempted vaccine worked. Men and women with a lifetime of experience in medicine were mystified at Stuart Redman's survival, especially after they injected him with the superflu under the guise of administering a sedative. Redman's immune system swiftly isolated and killed the virus, but with no visible sign of how.”

As more episodes air, we may find out if the miniseries really spells out the reason why certain people are not infected by the virus. Until then, let's wait and watch.

‘The Stand’ premieres on December 17, 2020, with the first episode titled ‘The End’ and subsequent episodes in the nine-episode limited-event series will follow every Thursday on CBS All Access.

‘The Stand’: Where Does the Term ‘Captain Trips’ Come From?

CBS All Access limited series based on Stephen King’s novel premiered Thursday

The first episode of CBS All Access’ limited series based on Stephen King’s novel “The Stand” premiered Thursday, and it couldn’t have come at a more apt time. The series follows a group of survivors after a superflu knocks out 99% of the world’s population, and it hits close to home as we face the very real, though not as fatal, coronavirus pandemic.

But the superflu in “The Stand” is known by a more casual, less scientific name: “Captain Trips.” If you’re wondering where that term came from and what it means, you’ve come to the right place.

The meaning and origin behind the phrase “Captain Trips” is never directly explained in King’s book. (It should be noted that the original version of “The Stand” was published in 1978, but King released a longer, updated version in 1990 that restored sections that had been cut from the original novel. The 1990 edition is the reference point for the series’ story).

“Captain Trips” does, however, appear in the book as a colloquial phrase used by young people to identify the virus. The virus was initially created by a military biological weapons lab under the codename “Project Blue,” and is also referred to in a more scientific context as “Blue virus,” “848-AB,” “A-prime” and “A6.” Other colloquialisms used to identify the respiratory illness in the book include “the rales,” “choking sickness,” “tube neck” and simply, “the superflu.”

King has never directly spelled out the origin of “Captain Trips.” It also wasn’t explained in his original 1969 short story “Night Surf” that spawned the book, nor in the 1978 version of “The Stand” novel, in the 1994 television miniseries or in the “Captain Trips” comic book. The phrase is mentioned in the first episode of the CBS All Access limited series, but not explained.

According to some online sci-fi fan forums , the best explanation of where the phrase comes from is that it originated with the late Grateful Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia, who was nicknamed “Captain Trips” because he was known for spiking people’s drinks with hallucinogenic drugs like LSD. The nickname has also been used to describe Alfred Matthew Hubbard, a pioneer of LSD in the 1950s who was dubbed “ The Original Captain Trips.”

Without an explanation from King himself, the most likely answer is that young people in the book began referring to the disease as “Captain Trips” because its symptoms can make a person delirious, resembling a drug-induced hangover. Another theory laid out in an archived Stephen King Reddit thread surmised, “I always thought it was because of the army = weaponised [sic] flu connection, captain trips and drops a jar of plague.”

Perhaps “The Stand” will eventually solve the “Captain Trips” mystery for us — keep watching to find out.

Episode 1 of “The Stand” is now streaming on CBS All Access.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

The Stand: Captain Trips Is STILL the Most Ridiculous Name for a Fictional Virus

Captain Trips is one of the names of the virus in The Stand, and it makes no sense in universe.

WARNING: The following contains spoilers for The Stand Episode 1, "The End," now streaming on CBS All Access .

Talk to any Stephen King fan, and they will acknowledge that the master of horror sometimes has a little trouble with the endings of his novels. There is the infamous and controversial scene with the kids in the sewers from It and the somewhat deflating ending in Under the Dome . In contrast to that, naming things has never been deemed a problem. The "shining" and the town of Castle Rock seem both fitting and perfectly acceptable names, which brings us to The Stand .

It is one of King’s most famous and beloved novels, and in 2020, the novel is more relevant and timely than ever, which may pay off for its new miniseries adaptation that debuted this past Thursday. However, one thing King got wrong is the naming of the virus Captain Trips. It may be the most ridiculous name for a fictional virus ever.

RELATED: The Stand Is an Underwhelming Adaptation of Stephen King's Epic

In the real world, viruses have simple, clear names, like the coronavirus. The name for the disease it causes has the simple abbreviation of COVID-19, which stands coronavirus disease, with the 19 tacked on to represent the year it was detected. There are tons of other viruses in the world, and most of them, like Ebola, are just known by their official name. Others, like Malaria, which is also known as Yellow Fever, may have different names that refer to their symptoms, in this case yellowing skin and fever. However, in all these cases, the names are simple and to the point.

This seems to be the case for Captain Trips, at least for its other names. The US government has been responsible for developing the novel’s virus in a military laboratory under the codename "Project Blue," and it is trying to deny and deflect any responsibility and downplay the severity and lethality of the virus. Since there is no official name that is recognized, it makes sense that the media and the population itself would come up with nicknames, like superflu, choking sickness or tube neck.

RELATED: The Stand Showrunner Teases Stephen King's New Coda to the Story

It is even plausible that these multiple names would all be coined in different parts of the country, since the book’s story is set in the last quarter of the last century, when the internet was in its infancy, and local television and newspapers were fairly common then. However, the name Captain Trips seems far fetched. It sounds more like a nickname college kids would use for a drug that gives them a great "trip" than it does for a serious virus.

It has never been publically made clear why Stephen King nicknamed the fictional virus Captain Trips, but there is a chance he named it after the Grateful Dead’s late singer, Jerry Garcia. Aside from being one of the most prolific, successful authors of our time, King is also a musician and big fan music, even writing a short story based around a town full of dead musicians called "You Know They Got a Hell of a Band."

RELATED: The Stand Reveals Randall Flagg's True Role in the Apocalypse

One band he is apparently a fan of is the Grateful Dead, even comparing himself to them at one point. There's also a connection between The Stand and the Grateful Dead, which is that frontman Jerry Garcia had the nickname Captain Trips for allegedly spiking the drinks of people around him with hallucinogenic drugs.

While that doesn’t have anything to do with an illness, it seems that King could've used the nickname of the singer for his virus. It would have probably been a better idea to keep the name shelved for something else that could've had a clearer connection to the band, if this was his reasoning. If it wasn't, then the virus' name lacks any justification for why it's so ridiculous.

The Stand stars Alexander Skarsgård as Randall Flagg, Whoopi Goldberg as Mother Abigail, James Marsden as Stu Redman, Odessa Young as Frannie Goldsmith, Jovan Adepo as Larry Underwood, Amber Heard as Nadine Cross, Owen Teague as Harold Lauder, Henry Zaga as Nick Andros, Brad William Henke as Tom Cullen, Irene Bedard as Ray Bretner, Nat Wolff as Lloyd Henreid, Eion Bailey as Weizak, Heather Graham as Rita Blakemoor, Katherine McNamara as Julie Lawry, Fiona Dourif as Ratwoman, Natalie Martinez as Dayna Jurgens, Hamish Linklater as Dr. Jim Ellis, Daniel Sunjata as Cobb and Greg Kinnear as Glen Bateman. The Stand releases new episodes Thursdays on CBS All Access.

KEEP READING: The Mandalorian Makes Clerks' Best Argument Star Wars Canon

‘Tripledemic:’ What Happens When Flu, RSV, and COVID-19 Cases Collide?

BY CARRIE MACMILLAN January 12, 2023

Doctors share tips on how to stay healthy this winter.

[Originally published: Nov. 22, 2022. Updated: Jan. 12, 2023]

Note: Information in this article was accurate at the time of original publication. Because information about COVID-19 changes rapidly, we encourage you to visit the websites of the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC), World Health Organization (WHO), and your state and local government for the latest information.

Last fall, as a common respiratory virus surged in children across the country, flu cases climbed, and COVID-19 simmered in the background, some medical experts worried about a potential “tripledemic.”

There’s no scientific definition for this term; it simply refers to a collision of RSV (respiratory syncytial virus), flu, and COVID-19 to the extent that it might overwhelm hospital emergency departments.

While all three viruses are present right now, they aren’t each peaking at the same time. Pediatric RSV and flu cases are now down; COVID-19 continues to increase in adults; and cases of adults with flu are declining in the elderly and somewhat stable among younger adults.

A big part of the flu increase in November, explains Scott Roberts, MD , a Yale Medicine infectious diseases specialist, was our lack of immunity from having not been exposed to the virus for several seasons due to masking and other precautions, many of which have fallen to the wayside.

We asked Dr. Roberts and Thomas Murray, MD, PhD , a Yale Medicine pediatric infectious diseases physician, more questions about how we can stay safe, especially as we spend more time indoors this winter.

What is happening with RSV and children?

RSV is a common and highly contagious respiratory virus that causes cold-like symptoms. Most kids are exposed to the virus by their second birthday and therefore develop a degree of immunity that makes future cases less troublesome.

Typically, kids and adults (who can still get it) recover within a week or two. “For the average healthy child, being under age 2 increases the risk of hospitalization. But even having said that, the vast majority of kids do not get hospitalized,” says Dr. Murray.

However, it can be more serious for the extremely young and very old, as well as anyone with a compromised immune system or underlying health conditions, such as congenital heart disease or cancer.

Plus, because of COVID-19 precautions, many young children haven’t been exposed to the virus in the last few years, but now with restrictions lifted, many are being infected. And in younger children, especially those less than 3 years old, it can lead to breathing difficulties because their lungs aren’t fully developed.

The good news, says Dr. Murray, is that this is not a new virus and health care providers know exactly how to take care of kids with RSV.

The problem last fall, Dr. Murray says, was the volume of sick children.

“Kids can get quite sick from it, but we know how to help them,” he says. “Children are admitted to the hospital for extra oxygen or other supportive measures such as positive pressure to help with breathing and keep the lungs open.”

There is no vaccine for RSV but there are several in development. Babies born prematurely or with an underlying medical condition may qualify for RSV antibody injections to help prevent severe disease.

What steps can we take to prevent illness?

Flu, COVID-19, and RSV are all respiratory viruses, but there are differences in how they spread.

“With COVID, we have appropriately focused on air quality, but many of these viruses can also spread by touching contaminated surfaces, which makes handwashing and cleaning contaminated surfaces really important,” Dr. Murray says.

Dr. Roberts agrees. “At the beginning of the pandemic, we were wiping down our fruit, vegetables, and everything with bleach, until we found out that COVID doesn’t spread through surfaces—but rather from sneezing, coughing, and expelling respiratory droplets and aerosols,” he says. “RSV spreads much more through contaminated surfaces. A kid rubs snot on their hands and puts the hand on someone else, and then that kid puts their hand in their mouth, and they can be infected. Handwashing and cleaning surfaces are more critical with RSV than with COVID.”

Flu, on other hand, is somewhere in the middle, and can spread from respiratory droplets, aerosols, and through contaminated surfaces, Dr. Roberts says. It’s important, therefore, to practice what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) calls “respiratory etiquette,” Dr. Murray says. “That means coughing into a tissue and disposing of it immediately in the garbage,” he says.

It may sound obvious, but the best prevention advice for all three illnesses is to avoid others who are sick. “And if you or your child is sick, stay away from others until you are improving and fever-free,” Dr. Murray says. “And if you have a baby, especially a newborn, be very careful about who visits in their first couple months of life. You only want people who are washing their hands and have no symptoms to be near the baby.”

How can we gather safely with others?

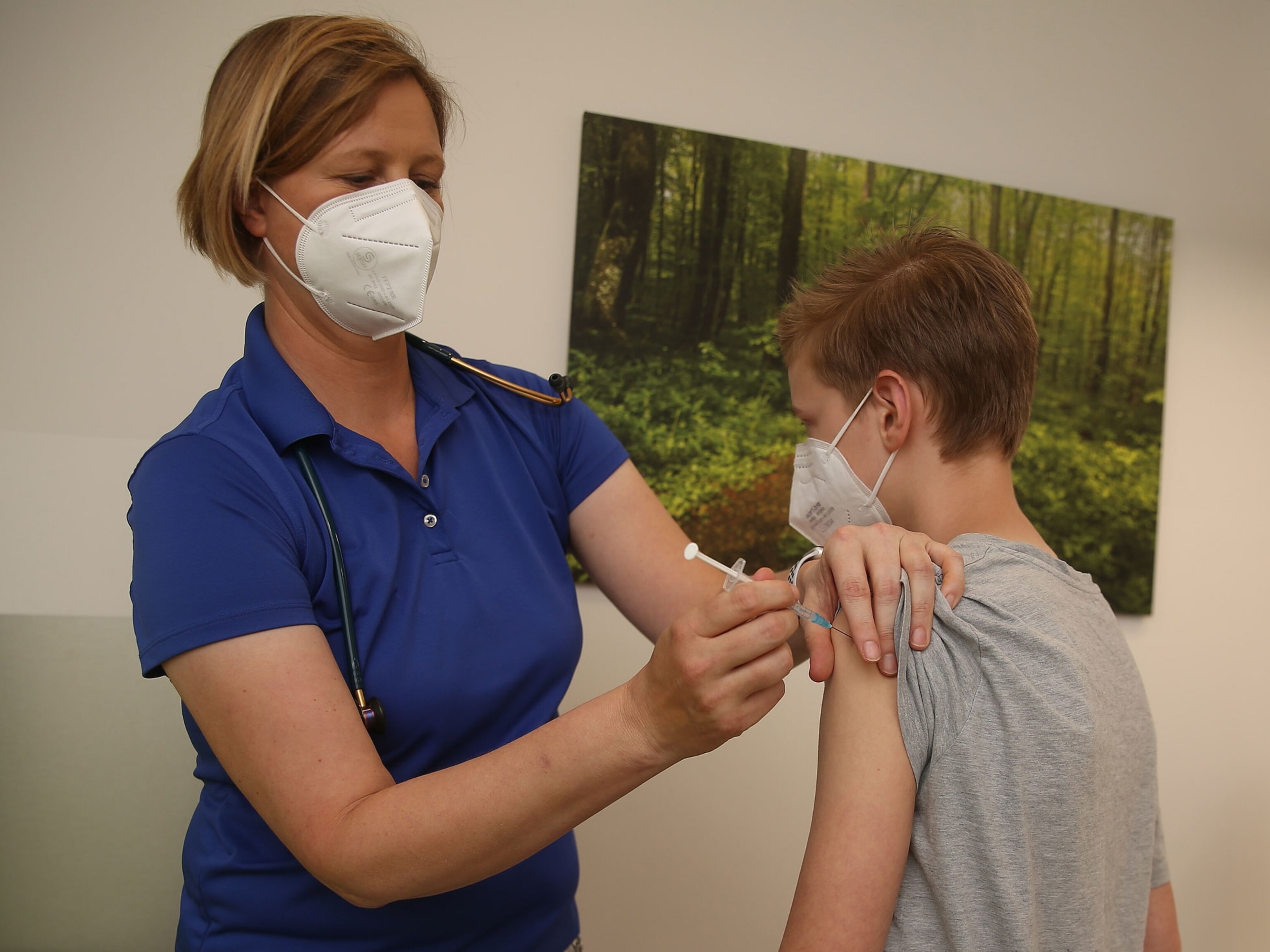

With colder weather keeping more people inside, it’s important to take certain precautions, doctors say. First and foremost, now is the time to get your flu shot and make sure you are up to date on your COVID-19 vaccination , including the new bivalent booster.

“The influenza vaccine may not completely prevent you from getting the flu, but it has a really good chance of keeping you from getting seriously ill and being hospitalized and dying,” Dr. Murray says.

If you are going to an indoor gathering, Dr. Roberts advises taking extra precautions in the week leading up to it. “In other words, don’t go to a big, indoor concert with tons of people shouting, where your odds of exposure to COVID or something else will be very high,” he says. “Plus, you can take a rapid test right before you go in the room for a gathering. If everybody does that, it’s an added layer of security. And if you are traveling, wear a mask, even if nobody else does.”

Dr. Murray says it’s also important to pay attention to symptoms. “If you have any symptoms, you really should not congregate with others. But if you insist, wear a mask and segregate yourself during activities such as eating, when you can’t be masked,” he says.

What is happening with COVID-19?

The COVID-19 variant XBB.1.5, yet another descendent of Omicron, is quickly spreading in the U.S. and has been described as the most transmissible form of the virus yet.

However, there is not yet evidence to suggest that it causes any more severe disease than other Omicron strains.

When should you call your child’s pediatrician?

“When your child starts to have cough and fever, it's always good to reach out to your pediatrician, to be in touch, says Dr. Murray. “That's very important. With babies, if you see really fast breathing or any blueness around the lips or what we call use of accessory muscles, which is if you start to see the shoulder blades when they're breathing or see the belly really going up and down really fast, or if the baby looks uncomfortable, those are reasons to come to the emergency room,” he says.

In the end, families need to be prepared that the hospital is a very busy place right now, he adds.

“If your child still looks well, then it's really important to start with your pediatrician. But certainly, if you're concerned, the emergency room evaluates your child quickly to see how sick they are,” Dr. Murray says. “And if they're quite sick, they will be seen faster.”

Information provided in Yale Medicine articles is for general informational purposes only. No content in the articles should ever be used as a substitute for medical advice from your doctor or other qualified clinician. Always seek the individual advice of your health care provider with any questions you have regarding a medical condition.

More news from Yale Medicine

Can ‘strategic masking’ protect against covid-19, flu, and rsv.

How Anti-Obesity Medications Can Help With Surgery

The Updated COVID Vaccines Are Here: 9 Things to Know

Let’s Talk About Bad Trips: Separating Difficult from Traumatic

Bad trips are a polarizing concept in psychedelics. acknowledging that they exist - and knowing how to work with them - can be healing..

Want to start a war on social media? Post something like this: “Bad trips exist.”

As somebody who has worked in the psychedelic space for years now and has supported many, many people during their trips, it’s time to come out of the closet and say it: people can be harmed by psychedelics, and bad trips exist.

But allow me to define the term “ bad trip ,” because the vague phrase has become too polarized to be meaningful.

When I talk about bad trips, I’m not talking about the harrowing, painful journeys to the underworld from which we return raw and exhausted, with some important piece of our healing work having been catalyzed.

When I talk about bad trips, I mean the trips that register in the body as a trauma or injury to the nervous system. And that is not , in fact, the same thing as a difficult trip.

What happens when we deny this truth is that we inadvertently alienate those who have had traumatic or harmful experiences. These people have endured a trauma, and are now being told that they have not.

So let’s talk about traumatic trips: The psychedelic experiences that leave us injured. Thankfully, they are rare.

I’m not just speaking from my observations as a clinician, but also from personal experience: I had a traumatic psychedelic experience on ayahuasca many years ago. I was decidedly “not okay” afterwards and required much time and support to recover.

Despite the shock and injury to my nervous system, I eventually used psychedelics again. In fact, in the eight or so years that have passed since the traumatic trip, I have openly supported the legalization of psychedelics, and have built two businesses centered around empowering people to heal with psychedelics.

I have also taken sabbaticals from my practice to work in other countries as a psychedelic facilitator. I am now a lead educator in the country’s first training program for psilocybin facilitators to be licensed by Oregon’s Higher Education Coordinating Commission (HECC). I’m a ketamine prescriber, and I train other prescribers in the use of ketamine for treating chronic pain and mood disorders. I lead and run intensive healing retreats. I’ve also taken my own fair share of mind altering substances in a variety of sets, settings, and time zones.

All of which is to say: I am no newcomer to the world of psychedelics.

And yet I cannot swallow the field’s echo-chamber-like mantra that “there is no such thing as a bad trip .” In fact, I find the rabidity with which some of my fellow cosmonauts deny the existence of bad trips to be rather disconcerting. In the more-than-one heated debate I’ve had about this topic, I’ve noticed certain patterns – or myths, if you will – around the topic of traumatic trips. I address each one here.

Myth: Bad Trips Only Happen When the Set and Setting Are Improper

If the word “only” didn’t appear in the above sentence, it would be true. In my experience in working with hundreds of patients who have used psychedelics – and in administering psychedelics myself – I’ll say that the vast majority of traumatic trips happen when the environment is not safe, calm, and supportive.

When we talk about set and setting in psychedelic harm reduction , we mean two things: (1) the person’s mindset when they took the drug, and (2) their physical environment. If somebody had just had an argument with their spouse before taking LSD, for example, that’s their set. If they were at a noisy, crowded music festival, that’s the setting. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the majority of bad trips happen when individuals on drugs feel overwhelmed in a noisy, chaotic setting like that of a concert or party. Drug-drug interactions are also often at play during difficult trips, for example, when people combine alcohol with psychedelics.

When people insist a little too strongly that, “There’s no such thing as a bad trip, if the set and setting are right,” I feel uneasy. It’s perhaps like asking a rape survivor, “Yeah, but what were you wearing?” (If you think the analogy of a bad trip and rape is too far of a reach, you luckily have never had a traumatic trip.)

There are other factors in psychedelic harm reduction that influence the outcomes. These include the substance being used, the dosage taken, and the people you’re with.

The night of my traumatic trip was the third of a three-night ayahuasca ceremony. I was there with my then-partner. I liked the other people attending. I trusted the facilitators completely and knew they were well trained and highly esteemed by their colleagues. The medicine was pure. The environment was soothing and well contained. The music was beautiful. The first half of the third ceremony was trippy, strange, and lovely.

After I drank my second dose of the brew, however, I was decidedly NOT OKAY. I will not describe the experience here, but I will say two things about it: (1) I felt like my nervous system was being gang raped, repeatedly, and (2) I can now absolutely understand why people with psychosis sometimes choose to die by suicide.

The facilitators of the circle took care of me, pulling me out of the ceremony space and letting me try to calm down outside. Somebody stayed with me at all times until I vomited up the salt water they gave me to drink.

There’s one factor of harm reduction we don’t discuss enough: dose. It’s possible that the second cup of ayahuasca I drank that night contained more voltage than my nervous system could handle – that it was too much, too fast, and too hard for me.

The Influence of Neuroticism

Aside from the environment, another factor that can predict bad trip potential is neuroticism. Neuroticism is one of the “Big Five” traits thought to collectively form the full picture of personality.

People who score high on neuroticism tend to overthink things, typically have a hard time relaxing, and may feel irritated in noisy settings or stressful situations. These folks are often described as “high strung.”

At least two studies have shown that people who score high on neuroticism scales are more likely to have a challenging psychedelic trip than those who score lower. [1] , [2] The theory behind this is that if a neurotic’s negative thoughts or feelings arise during a psychedelic trip, the person might get pulled into an amplification spiral of their own negativity.

But does that mean it’s somebody’s fault that if they tend towards neurosis and they have a bad trip? Aren’t psychedelics supposed to help heal negativity? What does it mean that the same drugs that help soothe negative thoughts and feelings can also make us feel worse? (Let a neurotic chew on that one.)

Once again, we could very easily slip into the territory of victim blaming if we are not mindful.

While writing this article, I took the Big Five Personality Test online. I scored in a higher-than-average percentile for negative emotionality (neuroticism). That may explain why grumpy cat is one of my heroes and why my friend Greg refers to me as “a female Larry David.” It could also explain why I’m one of the unlucky few who have had a traumatic psychedelic trip. (Side note: I also scored pretty high on open mindedness, so that could explain why got into psychedelics in the first place.)

Myth: Bad Trips Are Actually Just Difficult Experiences That Haven’t Been Integrated

I continue to stay in this field because traumatic trips are, indeed, exceedingly rare, and because the healing gains people typically experience from psychedelics are unparalleled by any other intervention I’ve found.

Working regularly with patients in non-ordinary states of consciousness, I see that the most challenging experiences are often the most rewarding. Drawing from my previous experiences in volunteering with the Zendo Project and White Bird , I teach my students the tenants of “trip sitting.”

As one of the Zendo principles states: difficult is not necessarily bad. Note that the phrase is not “difficult is not bad,” but rather, “ difficult is not necessarily bad. ” In other words, difficult can sometimes be bad.

Another layer to this argument is that if you wait long enough, the bad experience will prove itself to be good. This does, indeed, happen to many people after their challenging journeys. Yet there is a difference between suggesting this to a bad trip survivor and insisting that “everyone gets the trip they need.”

Many of my new-age peers have become allergic to the word “bad,” especially within the context of bad trips. “Is anything really bad?” I’m often asked. The argument here, as I understand it, is that with every cloud there comes a silver lining, and that silver lining might just hold a very valuable teaching for us.

I admit that my own traumatic trip gave me a lesson: It taught me that there is indeed such a thing as a bad trip. Another gift was that my bad trip helped me to better understand, validate, and support others who have been harmed by psychedelics. Another lesson was this: my bad trip was an amplifier of the toxic positivity that I see running rampant in the psychedelic field.

In fact, a patient once confessed to me, “I’m just so mad at her” – her being ayahuasca – “but everyone in the group is so in love with Great Grandmother that if I say one bad thing about her, it’ll be like heresy.” I noticed that he was clenching his jaw and only breathing into the upper part of his chest. I leaned forward, looked him in the eye, and said: “Tell me exactly what you think about that bitch – you won’t offend me.”

By the end of the hour, he had raged, wept, and laughed. His breath was reaching his abdomen and his jaw was relaxed. The client messaged me some days later, saying, “That was so healing for me just to be heard, to be able to say mean things without being afraid somebody would cancel me. Thank you.”

Perhaps for this client, “the medicine” was to be heard without anybody trying to stop him from expressing anger. Maybe the bad trip was just part of the arc that took him to that finale. I don’t know.

Myth: There’s No Such Thing as Bad

There’s that old story about the Zen master, whose son got a new horse. “What good luck!” The neighbors said. “We’ll see,” said the master. One day the son was thrown from the horse and broke his leg. “How terrible!” Said the neighbors. “We’ll see,” said the master. Then the country went to war, and the army came to recruit soldiers. Because the young man’s leg was broken, they army didn’t take him to battle. “How good!” said the neighbors. “We’ll see,” said the Zen master. Perhaps there is no good or bad.

What I’ve always found lacking in this story about the Zen master was the voice of his son – the one who actually fell from the horse.

Is a bad trip like falling from a horse? It absolutely can be. Yet something about the “you just haven’t integrated it yet, there’s gold there” argument feels like a dismissive bypass. Let us consider other situations in which we could apply such a statement:

- After getting food poisoning and vomiting for hours

- After taking penicillin and breaking out in a full body rash

- After going on a horrible date

- After surviving a sexual assault

- After your child has been diagnosed with a life-threatening illness

- After losing a loved one to cancer

- After surviving a terrible accident that has resulted in disability

- After your cat has been run over by a car

- After losing a house to foreclosure

Would we really tell the people in the above hypothetical situations that there was no such thing as bad shellfish? No such thing as a bad drug reaction or a bad date? No such thing as rape? No such thing as a bad diagnosis, a bad prognosis? Or how about just a bad day? Or something as non-threatening as a bad movie, a bad haircut, or a bad parking job? Would we really tell somebody whose child just died to avoid using the word “bad” to describe her condition?

Perhaps it is true that none of these things are bad, and that all of them are blessings in disguise. But would we really get righteous about it on social media, the way some of us do about denying bad trips?

And what’s so bad about saying “bad,” anyway? Must everything truly be a blessing? (The neurotic writing this article needs to know.)

I’d also like to share the story of Becks. Becks was a 24-year-old female patient of mine with anorexia nervosa who did MDMA-assisted psychotherapy to heal from PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) rooted in childhood sexual abuse.

In a follow-up visit, Becks told me that the MDMA-assisted therapy session (done with an underground provider) had done wonders for her. She was getting much more mileage out of her weekly therapy sessions. She was now remembering things she had repressed previously, and she was able to stay present when the memories arose.

Becks had also forgiven herself. She explained that without realizing it, she had blamed herself for what happened to her when she was a child, punishing herself through self-denigrating thoughts, food restriction, and high-risk drinking. Her MDMA-assisted therapy session helped her identify this pattern and realize that she didn’t deserve the blame or the punishment. Having forgiven herself, Becks was now sleeping better at night, eating when she was hungry, and avoiding alcohol. Clearly, much healing had occurred for her.

Yet Becks felt discouraged and worried. “I don’t think I’m doing it right,” she told me while pulling at the rings on her fingers.

“Why’s that?” I asked.

“Well,” she explained, “I know I’m supposed to get to this place where I feel like the trauma was a blessing – and that hasn’t happened.”

“You think you’re supposed to get to a place where you think that being repeatedly molested as a child is a blessing? ” I asked her.

“Yes,” she said with a defeated sigh as she looked at her shoes.

“Where’d you get that idea?”

Her head snapped up to look at me, breathless, huge-eyed. And then she burst out laughing. The laughter turned to tears. She sobbed and babbled something about a podcast she’d heard. Then she laughed some more. Her face lit up and the color returned to her cheeks.

“Becks, was being molested by your stepbrother every night a blessing?” I asked her.

“No, it was a fucking horrible nightmare that I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy,” she declared.

“Okay,” I said, “and is it possible that it was a fucking horrible nightmare and that you still get to heal and have a happy adult life starting right now?” I asked.

“ Fuck yeah,” she said. And the look on her face told me she believed it.

(This, by the way, is what happens when you go to a doctor who scores high on neuroticism scales: We acknowledge and celebrate that life might be a fucked up mess sometimes, and that we can still heal even if we don’t buy into toxic positivity.)

(Also: I do have patients who come to see their traumas as gifts. It truly is a powerful and important step in their healing. But let’s not assume that healing cannot happen in other forms. Everyone’s path is different and valid.)

Myth: Talking About Bad Trips Is Going to Harm the Psychedelic Movement

On the day I graduated from medical school, I took an oath to First, Do No Harm . Sometimes, First, Do No Harm means doing the uncomfortable thing or saying what others don’t want to hear. In this case, it means acknowledging that there are risks to using psychedelic substances, and a traumatic trip is one of those risks.

Every therapy, every medicine, every experience comes with risks and benefits. One risk of taking vitamin C is that too much can cause diarrhea. One risk of antibiotics is that they can lead to vaginal yeast infections. One risk of using acetaminophen (paracetamol) is that it’s hard on the liver. One risk of eating a vegan diet is that it can deplete vitamin B12 stores and subsequently trigger depression. One risk of a life-saving surgery is that it can result in a lethal infection. And so forth.

Psychedelic medicines also come with their risks, and the risk of a traumatic trip should be on that list. Admittedly, it should be in small letters, towards the bottom of the list, next to the words “very rare when used in therapeutic contexts.” But traumatic trips are, in fact, “a thing.” They’re part of the fine print.

As far as I know, bad trips have not been reported in any of the clinical trials on psychedelics – but keep in mind that we haven’t had too many people go through the clinical trials as compared to the number of folks doing psychedelics “in the wild.” Bad trips may have also been down-played in the trials as “dysphoria” or “agitation” by the researchers.

Are the possible risks of psychedelic medicines worth wagering for the potential benefits? The answer to that question can only be answered on a case-by-case basis – as with any intervention.

For me personally: The healing engendered by psychedelics has far outweighed and more than redeemed the harm I’ve endured. Every time I take a psychedelic medicine now, I understand that I am taking a risk, and I make the clear, informed decision to proceed – or not to proceed, depending on the circumstance.

When I advocate for the destigmatization and legalization of psychedelics, furthermore, I don’t just act out of love for the movement: I act out of love for my patients.

What’s going to injure the psychedelic movement even more than a level-headed discussion about traumatic trips is the harm that may be caused by denying them.

How to Talk to a Bad Trip Survivor

So, what should we say to a survivor of a traumatic trip? Anything but: “There’s no such thing as a bad trip.”

If somebody tells you they’ve endured a bad trip, treat them as if they’d just told you that they survived an accident, an assault, or another kind of shock. Offer them comfort and support. Listen. Don’t ask them to prove the truth of what they say happened.

Essentially: treat them as you would treat the survivor of any kind of experience that was too much, too hard, and/or too fast for their mind, body, or spirit.

Remember that the word “trauma” does not refer to the distressing event itself, but rather to the resulting emotional and neurological response. Trauma can harm a person’s sense of Self, their sense of safety, their ability to navigate relationships, and their ability to regulate their emotions. Trauma, in other words, is injury to the nervous system that ripples outward. (To be clear: Trauma does not mean simply feeling uncomfortable or offended, as some people mistakenly use it.)

Even if integration of the experience would be helpful for the survivor – and might even help them stop using the term “bad trip” to describe it – that cannot happen at the beginning. The first thing the bad trip survivor likely needs is to know that they are safe now . The nightmare has ended, and they are loved and supported by trustworthy people who care.

How can we help others feel safe? By our presence. By regulating our own breath. By listening. By letting them know that we believe them. By showing empathy. By making them soup, gifting them a massage, or offering to pick their kids up from school. By being kind.

Even if the traumatic trip was the result of poor planning, improper set and setting, or other user error, hold your tongue for now. Think of how you might react if a friend was in a terrible car accident that resulted from driving when they were overly tired.

Think of how you might respond if a child dragged a chair to the kitchen counter and climbed atop it to try and reach the off-limits cookie jar sitting high up on a shelf – only to tumble backwards and slam onto the floor. Would you shout, “Well, that’s what you get for climbing on the chair!” while the poor kiddo cried on the linoleum? I hope not. I hope you would sit by their side, hug them, and stroke their hair. Once you felt their breathing return to normal and the smile return to their face – and not a second sooner – might you ask, “Honey, remember what we said about climbing on the furniture?”

Healing From My Bad Trip

It took me almost eight years to feel like I had fully integrated my bad trip. Curiously, what helped me complete the arc from wound to health was a peyote ceremony.

What prolonged my healing was people insisting that there was no such thing as a bad trip. I heard this line in my ayahuasca circle, at psychedelic conferences, on social media, on podcasts, and in books. The experience-denying and victim-blaming made me feel angry and alone.

Another factor that delayed my full recovery was peer pressure. Buckling to the well-intentioned insistence of friends, I returned to the ayahuasca circle (and other psychedelic circles) sooner than I truly wanted to. This meant that I was taking medicines with a mindset of doubt and fear, which resulted in several dysphoric, confusing, and terrifying journeys that only compounded the injury.

I was fortunate to find a healer who believed in bad trips and who confirmed that I was not fully in my body. Through regular sessions, I was able to return. While my therapist hadn’t had much psychedelic experience herself, she at least believed me. That allowed us to start from a place of trust and not from a place of defensiveness. I also took a break from psychedelics and instead cultivated gentler, more predictable health-affirming practices like singing and going to the gym.

Years after the experience, I read about the concept of “too much, too hard, too fast” in a book about psychedelic facilitation. I felt a surge of heat rush to my face as I read the words; hot tears filled my eyes. I hadn’t made it up. It had happened to me. I wasn’t weak, or stupid, or crazy. But why was the truth so hard for other people to accept?

I’m grateful to my own stubborn will to get better – to that spark within me that keeps me seeking out people, places, and things that can help me heal, grow, and learn.

There was, indeed, some good that came from my bad trip on ayahuasca all those years ago. The seams of that horrific shroud were sewn with golden thread. I am grateful for the blessings gleaned.

I am also grateful to my unconditionally supportive family, friends, and partner, and to Grandfather Peyote for helping me weave the blessings into my life and pull back the heavy curtain.

I had a bad trip, and that’s okay.

And you know? Considering that I’m a neurotic, I’m pretty proud of myself for saying so.

Follow your Curiosity

[1] Barrett FS, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Neuroticism is associated with challenging experiences with psilocybin mushrooms. Pers Individ Dif. 2017 Oct 15;117:155-160. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.004 .

[2] Petter Grahl Johnstad (2021) The Psychedelic Personality: Personality Structure and Associations in a Sample of Psychedelics Users, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 53:2, 97-103, DOI: 10.1080/02791072.2020.1842569

You may also be interested in:

Harm Reduction

Mental Health

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Traveler's diarrhea

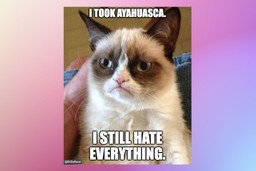

Gastrointestinal tract

Your digestive tract stretches from your mouth to your anus. It includes the organs necessary to digest food, absorb nutrients and process waste.

Traveler's diarrhea is a digestive tract disorder that commonly causes loose stools and stomach cramps. It's caused by eating contaminated food or drinking contaminated water. Fortunately, traveler's diarrhea usually isn't serious in most people — it's just unpleasant.

When you visit a place where the climate or sanitary practices are different from yours at home, you have an increased risk of developing traveler's diarrhea.

To reduce your risk of traveler's diarrhea, be careful about what you eat and drink while traveling. If you do develop traveler's diarrhea, chances are it will go away without treatment. However, it's a good idea to have doctor-approved medicines with you when you travel to high-risk areas. This way, you'll be prepared in case diarrhea gets severe or won't go away.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Book of Home Remedies

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Digestive Health

Traveler's diarrhea may begin suddenly during your trip or shortly after you return home. Most people improve within 1 to 2 days without treatment and recover completely within a week. However, you can have multiple episodes of traveler's diarrhea during one trip.

The most common symptoms of traveler's diarrhea are:

- Suddenly passing three or more looser watery stools a day.

- An urgent need to pass stool.

- Stomach cramps.

Sometimes, people experience moderate to severe dehydration, ongoing vomiting, a high fever, bloody stools, or severe pain in the belly or rectum. If you or your child experiences any of these symptoms or if the diarrhea lasts longer than a few days, it's time to see a health care professional.

When to see a doctor

Traveler's diarrhea usually goes away on its own within several days. Symptoms may last longer and be more severe if it's caused by certain bacteria or parasites. In such cases, you may need prescription medicines to help you get better.

If you're an adult, see your doctor if:

- Your diarrhea lasts beyond two days.

- You become dehydrated.

- You have severe stomach or rectal pain.

- You have bloody or black stools.

- You have a fever above 102 F (39 C).

While traveling internationally, a local embassy or consulate may be able to help you find a well-regarded medical professional who speaks your language.

Be especially cautious with children because traveler's diarrhea can cause severe dehydration in a short time. Call a doctor if your child is sick and has any of the following symptoms:

- Ongoing vomiting.

- A fever of 102 F (39 C) or more.

- Bloody stools or severe diarrhea.

- Dry mouth or crying without tears.

- Signs of being unusually sleepy, drowsy or unresponsive.

- Decreased volume of urine, including fewer wet diapers in infants.

It's possible that traveler's diarrhea may stem from the stress of traveling or a change in diet. But usually infectious agents — such as bacteria, viruses or parasites — are to blame. You typically develop traveler's diarrhea after ingesting food or water contaminated with organisms from feces.

So why aren't natives of high-risk countries affected in the same way? Often their bodies have become used to the bacteria and have developed immunity to them.

Risk factors

Each year millions of international travelers experience traveler's diarrhea. High-risk destinations for traveler's diarrhea include areas of:

- Central America.

- South America.

- South Asia and Southeast Asia.

Traveling to Eastern Europe, South Africa, Central and East Asia, the Middle East, and a few Caribbean islands also poses some risk. However, your risk of traveler's diarrhea is generally low in Northern and Western Europe, Japan, Canada, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States.

Your chances of getting traveler's diarrhea are mostly determined by your destination. But certain groups of people have a greater risk of developing the condition. These include:

- Young adults. The condition is slightly more common in young adult tourists. Though the reasons why aren't clear, it's possible that young adults lack acquired immunity. They may also be more adventurous than older people in their travels and dietary choices, or they may be less careful about avoiding contaminated foods.

- People with weakened immune systems. A weakened immune system due to an underlying illness or immune-suppressing medicines such as corticosteroids increases risk of infections.

- People with diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, or severe kidney, liver or heart disease. These conditions can leave you more prone to infection or increase your risk of a more-severe infection.

- People who take acid blockers or antacids. Acid in the stomach tends to destroy organisms, so a reduction in stomach acid may leave more opportunity for bacterial survival.

- People who travel during certain seasons. The risk of traveler's diarrhea varies by season in certain parts of the world. For example, risk is highest in South Asia during the hot months just before the monsoons.

Complications

Because you lose vital fluids, salts and minerals during a bout with traveler's diarrhea, you may become dehydrated, especially during the summer months. Dehydration is especially dangerous for children, older adults and people with weakened immune systems.

Dehydration caused by diarrhea can cause serious complications, including organ damage, shock or coma. Symptoms of dehydration include a very dry mouth, intense thirst, little or no urination, dizziness, or extreme weakness.

Watch what you eat

The general rule of thumb when traveling to another country is this: Boil it, cook it, peel it or forget it. But it's still possible to get sick even if you follow these rules.

Other tips that may help decrease your risk of getting sick include:

- Don't consume food from street vendors.

- Don't consume unpasteurized milk and dairy products, including ice cream.

- Don't eat raw or undercooked meat, fish and shellfish.

- Don't eat moist food at room temperature, such as sauces and buffet offerings.

- Eat foods that are well cooked and served hot.

- Stick to fruits and vegetables that you can peel yourself, such as bananas, oranges and avocados. Stay away from salads and from fruits you can't peel, such as grapes and berries.

- Be aware that alcohol in a drink won't keep you safe from contaminated water or ice.

Don't drink the water

When visiting high-risk areas, keep the following tips in mind:

- Don't drink unsterilized water — from tap, well or stream. If you need to consume local water, boil it for three minutes. Let the water cool naturally and store it in a clean covered container.

- Don't use locally made ice cubes or drink mixed fruit juices made with tap water.

- Beware of sliced fruit that may have been washed in contaminated water.

- Use bottled or boiled water to mix baby formula.

- Order hot beverages, such as coffee or tea, and make sure they're steaming hot.

- Feel free to drink canned or bottled drinks in their original containers — including water, carbonated beverages, beer or wine — as long as you break the seals on the containers yourself. Wipe off any can or bottle before drinking or pouring.

- Use bottled water to brush your teeth.

- Don't swim in water that may be contaminated.

- Keep your mouth closed while showering.

If it's not possible to buy bottled water or boil your water, bring some means to purify water. Consider a water-filter pump with a microstrainer filter that can filter out small microorganisms.

You also can chemically disinfect water with iodine or chlorine. Iodine tends to be more effective, but is best reserved for short trips, as too much iodine can be harmful to your system. You can purchase water-disinfecting tablets containing chlorine, iodine tablets or crystals, or other disinfecting agents at camping stores and pharmacies. Be sure to follow the directions on the package.

Follow additional tips

Here are other ways to reduce your risk of traveler's diarrhea:

- Make sure dishes and utensils are clean and dry before using them.

- Wash your hands often and always before eating. If washing isn't possible, use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol to clean your hands before eating.

- Seek out food items that require little handling in preparation.

- Keep children from putting things — including their dirty hands — in their mouths. If possible, keep infants from crawling on dirty floors.

- Tie a colored ribbon around the bathroom faucet to remind you not to drink — or brush your teeth with — tap water.

Other preventive measures

Public health experts generally don't recommend taking antibiotics to prevent traveler's diarrhea, because doing so can contribute to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Antibiotics provide no protection against viruses and parasites, but they can give travelers a false sense of security about the risks of consuming local foods and beverages. They also can cause unpleasant side effects, such as skin rashes, skin reactions to the sun and vaginal yeast infections.

As a preventive measure, some doctors suggest taking bismuth subsalicylate, which has been shown to decrease the likelihood of diarrhea. However, don't take this medicine for longer than three weeks, and don't take it at all if you're pregnant or allergic to aspirin. Talk to your doctor before taking bismuth subsalicylate if you're taking certain medicines, such as anticoagulants.

Common harmless side effects of bismuth subsalicylate include a black-colored tongue and dark stools. In some cases, it can cause constipation, nausea and, rarely, ringing in your ears, called tinnitus.

- Feldman M, et al., eds. Infectious enteritis and proctocolitis. In: Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. 11th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 25, 2021.

- LaRocque R, et al. Travelers' diarrhea: Microbiology, epidemiology, and prevention. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 26, 2021.

- Ferri FF. Traveler diarrhea. In: Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2023. Elsevier; 2023. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- Diarrhea. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/diarrhea. Accessed April 27, 2023.

- Travelers' diarrhea. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2020/preparing-international-travelers/travelers-diarrhea. Accessed April 28, 2023.

- LaRocque R, et al. Travelers' diarrhea: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 26, 2021.

- Khanna S (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. May 29, 2021.

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION

Home | About WTO | News & events | Trade topics | WTO membership | Documents & resources | External relations

Contact us | Site map | A-Z | Search

español français

Discussion on the extension of COVID-19 IP waiver

At MC12, trade ministers adopted the Ministerial Decision on the TRIPS Agreement, which gives members greater scope to take direct action to diversify production of COVID-19 vaccines and to override the exclusive effect of patents through a targeted waiver over the next five years. It addresses specific problems identified during the pandemic and aims to help diversify vaccine production capacity. It also contains a commitment that no later than six months from the date of the decision (17 June), members will decide on its possible extension to cover the production and supply of COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics.

Many members took the floor to welcome the successful outcome at MC12, saying it proved that WTO members can put aside differences and work together to respond to the most urgent health challenges.

A group of developing members who support an extension of the waiver to cover COVID-19 diagnostics and therapeutics circulated a proposal at the meeting including an indicative timeline for the TRIPS Council's next steps in this regard.

These members argued that the waiver on COVID-19 vaccines falls short of their expectation and is not enough to help developing countries comprehensively address current and future health challenges. Equitable access to therapeutics and diagnostics, as pointed out by the World Health Organization (WHO), is critical in helping detect new cases and new variants. They said this waiver extension needs to be discussed with a sense of urgency given the fact that many least developed countries (LDCs) lack access to life-saving drugs and testing therapeutics.

Many developing countries supported the initiative. They highlighted the joint statement made by the three Director Generals of the WHO, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) and the WTO in June 2021 reaffirming their commitment to intensifying cooperation in support of access to medical technologies worldwide to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic, including vaccines, therapeutics and diagnostics. There was also a shared view that the negotiation process for the waiver extension should be open, inclusive and transparent.

Other members cautioned that more time was needed to conduct domestic consultations on a possible extension of the waiver to therapeutics and diagnostics. Some members also flagged the importance of an evidence-based negotiation as there was no evidence that intellectual property did indeed constitute a barrier to accessing COVID-19 vaccines. Some also reiterated the need for members to fully make use of all the flexibilities that already exist in the TRIPS Agreement (including compulsory licensing) before requesting new flexibilities.

The chair, Ambassador Lansana Gberie (Sierra Leone), asked members that were ready to engage to commence discussing this matter in various configurations. He encouraged members to individually report on progress to the General Council meeting on 25-26 July while some members may need more time to deliberate on the matter, he noted. The chair will inform members how best to structure discussions on this matter going forward, he added.

Members also agreed to continue exchanges under the agenda item of IP and COVID-19 so that the TRIPS Council can keep abreast of new IP measures in relation to COVID-19 and share relevant experience. The Council also decided that the Secretariat will continue compiling and updating all COVID-related IP measures in its document “ COVID-19: Measures regarding Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights ” to serve as the basis for members' exchanges.

Members noted that this exercise is also in line with the Ministerial Declaration on the WTO Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic and Preparedness for Future Pandemics which provides for ongoing analysis of lessons learned and challenges experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic within the relevant WTO bodies.

IP and innovation: IP licensing opportunities

Under an item on IP and Innovation which had been requested by Australia, Canada, the European Union, Hong Kong China, Japan, Singapore, Switzerland, Chinese Taipei, the United Kingdom and the United States, the co-sponsors presented their new submission with a focus on IP licensing opportunities ( IP/C/W/691 , circulated on 23 June).

The co-sponsors highlighted several major ways owners of IP assets can secure a broader reach for their products and services through licensing agreements, which enable IP owners to allow the licensee to make or sell the invention during the licence period. This includes licensing of patents, copyright, trademarks and know-how.

The proponents shared experiences on how to apply different licensing models and build up a friendly ecosystem to foster IP trading. To overcome the knowledge gap and complexity of implementing IP licensing, these countries have developed various toolkits to provide training, online guidelines, contract templates, legal services and dispute settlement so that small businesses and individuals can effectively participate in IP partnerships.

Members welcomed the discussion on IP innovation and IP licensing, with some sharing their domestic practices. WIPO introduced its recent activities in support of IP licensing, including the establishment of an IP and innovation ecosystems sector, the work of the WIPO arbitration and mediation centre, and guidance to help start-ups develop their IP strategy.

Non-violation and situation complaints

WTO members welcomed the decision adopted at MC12 to extend the moratorium on non-violation and situation complaints (NVSCs) under the TRIPS Agreement until the next Ministerial Conference (MC13). The decision tasked members to continue examining possible scope and modalities for NVSCs and to make recommendations to MC13.

This concerns the longstanding issue of whether members should have the right to bring dispute cases to the WTO if they consider that another member's action or a specific situation has deprived them of an expected benefit under the TRIPS Agreement, even if no specific TRIPS obligation has been violated.

This moratorium was originally set to last for five years (1995–99), but it has been extended a number of times since then in the absence of agreement by members on what the scope and modalities could look like if non-violation and situation complaints were to apply to the TRIPS Agreement.

At the meeting, several developing countries suggested continuing the examination of the scope and modalities of such complaints, with the aim of making it applicable to WTO dispute settlement. Some members backed the idea of seeking a permanent solution on this matter while others were concerned that allowing NVSC dispute complaints might jeopardize the flexibilities granted in the TRIPS Agreement.

More information on the TRIPS non-violation issue is available here .

Technical cooperation and capacity building

WIPO briefed the meeting on the WHO-WIPO-WTO COVID-19 Technical Assistance Platform , which offers a one-stop shop to help members and WTO accession candidates address their capacity building needs to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The chair urged members to submit information on their activities in technical cooperation and capacity building as well as incentives for technology transfer by 12 September in preparation for the end-of-year annual review. Members are encouraged to use the online submission system ( e-TRIPS ) to make submissions.

Other matters

The European Free Trade Association was granted observer status for the next Council meeting.

Next meeting

The next TRIPS Council meeting is scheduled for 12-13 October 2022.

Problems viewing this page? If so, please contact [email protected] giving details of the operating system and web browser you are using.

- Today's news

- Reviews and deals

- Climate change

- 2024 election

- Fall allergies

- Health news

- Mental health

- Sexual health

- Family health

- So mini ways

- Unapologetically

- Buying guides

Entertainment

- How to Watch

- My watchlist

- Stock market

- Biden economy

- Personal finance

- Stocks: most active

- Stocks: gainers

- Stocks: losers

- Trending tickers

- World indices

- US Treasury bonds

- Top mutual funds

- Highest open interest

- Highest implied volatility

- Currency converter

- Basic materials

- Communication services

- Consumer cyclical

- Consumer defensive

- Financial services

- Industrials

- Real estate

- Mutual funds

- Credit cards

- Credit card rates

- Balance transfer credit cards

- Business credit cards

- Cash back credit cards

- Rewards credit cards

- Travel credit cards

- Checking accounts

- Online checking accounts

- High-yield savings accounts

- Money market accounts

- Personal loans

- Student loans

- Car insurance

- Home buying

- Options pit

- Investment ideas

- Research reports

- Fantasy football

- Pro Pick 'Em

- College Pick 'Em

- Fantasy baseball

- Fantasy hockey

- Fantasy basketball

- Download the app

- Daily fantasy

- Scores and schedules

- GameChannel

- World Baseball Classic

- Premier League

- CONCACAF League

- Champions League

- Motorsports

- Horse racing

- Newsletters

New on Yahoo

- Privacy Dashboard

‘The Stand': Where Does the Term ‘Captain Trips’ Come From?

The first episode of CBS All Access’ limited series based on Stephen King’s novel “The Stand” premiered Thursday, and it couldn’t have come at a more apt time. The series follows a group of survivors after a superflu knocks out 99% of the world’s population, and it hits close to home as we face the very real, though not as fatal, coronavirus pandemic.

But the superflu in “The Stand” is known by a more casual, less scientific name: “Captain Trips.” If you’re wondering where that term came from and what it means, you’ve come to the right place.