- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Do Police Officers Make Schools Safer or More Dangerous?

School resource officers were supposed to prevent mass shootings and juvenile crime. But some schools are eliminating them amid a clamor from students after George Floyd’s death.

By Dana Goldstein

The national reckoning over police violence has spread to schools, with several districts choosing in recent days to sever their relationships with local police departments out of concern that the officers patrolling their hallways represent more of a threat than a form of protection.

School districts in Minneapolis , Seattle and Portland, Ore. , have all promised to remove officers, with the Seattle superintendent saying the presence of armed police officers “prohibits many students and staff from feeling fully safe.” In Oakland, Calif., leaders expressed support on Wednesday for eliminating the district’s internal police force, while the Denver Board of Education voted unanimously on Thursday to end its police contract .

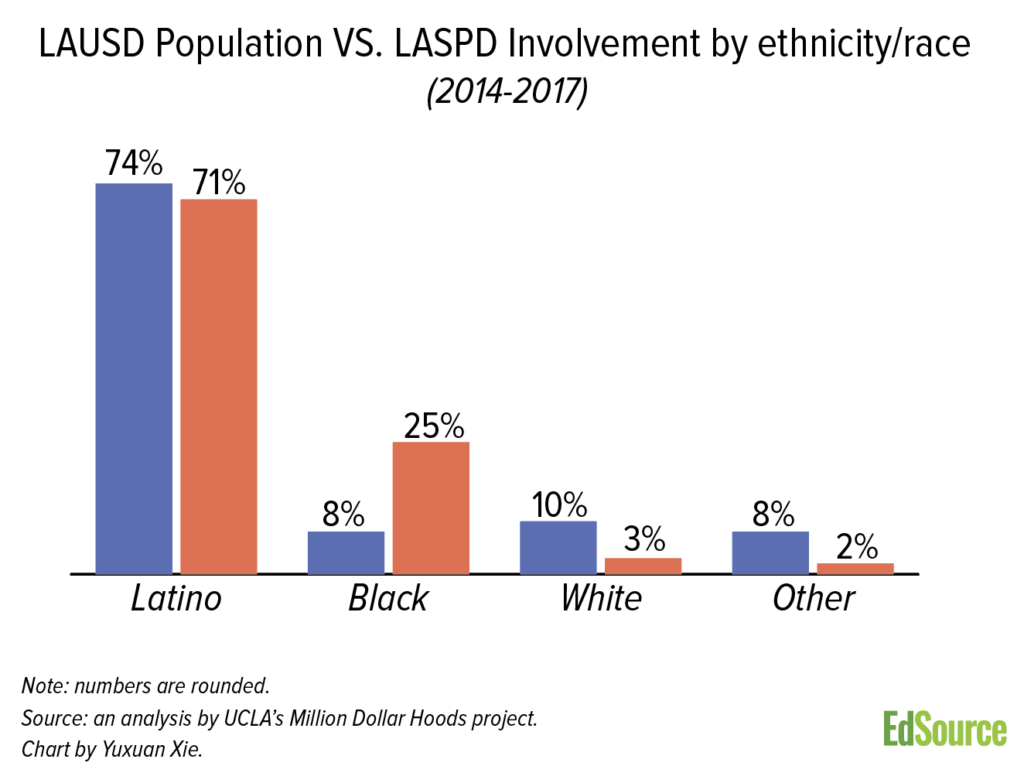

In Los Angeles and Chicago, two of the country’s three largest school districts, teachers’ unions are pushing to get the police out, showing a willingness to confront another politically powerful, heavily unionized profession.

Some teachers and students, African-Americans in particular, say they consider officers on campus a danger, rather than a bulwark against everything from fights to drug use to mass shootings.

There has been no shortage of episodes to back up their concerns. In Orange County, Fla., in November, a school resource officer was fired after a video showed him grasping a middle school student’s hair and yanking her head back during an arrest after students fought near school grounds. A few weeks later, an officer assigned to a school in Vance County, N.C., lost his job after he repeatedly slammed an 11-year-old boy to the ground.

Nadera Powell, 17, said seeing officers in the hallways at Venice High School in Los Angeles sent a clear message to black students like her: “Don’t get too comfortable, regardless of whether this school is your second home. We have you on watch. We are able to take legal or even physical action against you.”

During student walkouts to protest gun violence and push for climate action over the past two years, some officers blocked students from leaving school grounds or clashed verbally with protesters, she recalled. At Fremont High School in another part of Los Angeles, where the student body is about 90 percent Latino , the police used pepper spray in November to break up a fight.

“All people who are of color here are looked at as a threat,” Ms. Powell said.

For years, activists have called on districts to rein in campus police. They cite data showing that mass shootings like those in Parkland, Fla., or Newtown, Conn., are rare , and that crime on school grounds has generally declined in recent years.

The presence of officers in hallways has a profound impact on students of color and those with disabilities, who, according to several analyses and studies, are more likely to be harshly punished for ordinary misbehavior.

Still, efforts to remove school resource officers face the same pushback as a broader national effort to reduce funding for police departments: resistance from the police themselves, who are often politically powerful, and concern from some parents and school officials that removing officers could leave schools and students vulnerable.

In Oakland, Jumoke Hinton Hodge, a school board member, said that although she strongly supported the Black Lives Matter movement, she opposed the effort to eliminate district police officers. Those officers are better equipped to work with teenagers than are the city police, who could be called to schools more often if the district no longer had its own force, she said.

The district’s officers train to prevent school shootings, Ms. Hinton Hodge said, and they respond to students who have reported sexual abuse or are at risk of suicide. The proposal to eliminate the force felt rushed, she said, and would leave the district without an adequate safety plan.

“Are you here for the long haul, about a movement?” she asked. “Or are you in a moment?”

In New York City last weekend, hundreds of teachers and students marched in a protest calling for the police to be removed from schools and replaced by a new crop of guidance counselors and social workers. Mayor Bill de Blasio committed to diverting some of the Police Department’s funding to social services for children, but has so far not shown a willingness to significantly reduce police presence in hallways.

Mayor Lori Lightfoot of Chicago has rejected calls from the teachers’ union and others to remove officers from schools, saying they are needed to provide security.

Both mayors control their city’s school systems. It is districts with elected school boards, which are more independent from other local government agencies, that are currently driving the wave of change.

Mo Canady, executive director of the National Association of School Resource Officers, said he was disappointed by attempts to link school policing to the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis. He called Mr. Floyd’s death during an arrest “the most horrific police abuse situation I’ve seen in my career.”

Well-trained school resource officers operate more like counselors and educators, Mr. Canady said, working with students to defuse peer conflict and address issues such as drug and alcohol use. He suggested that disproportionate discipline and arrest rates for students of color and those with disabilities could be driven by the actions of police officers coming off the street to respond to one-off calls from schools, or by campus officers who lack adequate training in concepts such as implicit bias.

“The message to the districts has to be, ‘Don’t throw the baby out with the bath water,’” Mr. Canady said.

But as schools face significant budget cuts brought about by the coronavirus pandemic , some students, educators and policymakers say it would be wiser to hire psychologists to provide counseling and nurses to advise students on drugs and alcohol, instead of training police officers to do such tasks.

In Prince George’s County, Md., outside of Washington, Joshua Omolola, 18, has marched to protest the killing of Mr. Floyd. Now, as the student member of the Board of Education, he is supporting a proposal to remove police officers from the county’s schools, whose students are predominantly black and Hispanic.

The millions the county spends annually on school policing should be reallocated to mental health services, Mr. Omolola argued, to treat the root causes of student behavioral problems.

Police departments have typically responded to calls from school employees, but the everyday presence of officers in hallways did not become widespread until the 1990s. That was when concern over mass shootings, drug abuse and juvenile crime led federal and state officials to offer local districts money to hire officers and purchase law enforcement equipment, such as metal detectors.

By the 2013-14 school year, two-thirds of high school students, 45 percent of middle schoolers and 19 percent of elementary school students attended a school with a police officer, according to a 2018 report from the Urban Institute . Majority black and Hispanic schools are more likely to have officers on campus than majority white schools.

But when the Congressional Research Service reported on the effectiveness of school resource officers in 2013, it concluded that there was little rigorous research showing a connection between the presence of police officers in schools and changes in crime or student discipline rates.

Activists who have worked for years to remove officers from hallways said they were shocked at the speed with which school districts were promising significant change after Mr. Floyd’s death. The coming weeks may equal the impact of a decade’s worth of incremental reforms, according to Jasmine Dellafosse, an organizer in Stockton, Calif., east of San Francisco, with the Gathering for Justice, a nonprofit group.

After the A.C.L.U. Foundation of Northern California and the state Department of Justice investigated harsh discipline practices in Stockton schools, the district police force agreed last year to establish new restrictions on the use of force and on when to arrest students.

Now the school board plans to consider, later this month, a resolution to remove police officers entirely from schools and to reallocate their budget to programs such as ethnic studies , counseling and restorative justice .

“There won’t be real change,” Ms. Dellafosse said, “until police are out of the schools.”

Eliza Shapiro and Erica L. Green contributed reporting.

Dana Goldstein is a national correspondent, writing about how education policies impact families, students and teachers across the country. She is the author of “The Teacher Wars: A History of America's Most Embattled Profession.” More about Dana Goldstein

Gun Violence in America

The Gun Lobby’s Hidden Hand: In the battle to dismantle gun restrictions, a Georgetown professor keeps turning up in the legal briefs and judges’ rulings. His seemingly independent work has undisclosed ties to pro-gun interests .

A Novel Legal Strategy: Families of victims of the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas, have sued a video game, a gun maker and Instagram , claiming they helped to groom and equip the shooter.

Bump Stocks : The Supreme Court overturned a ban on the attachments, a restriction that had gained wide support when Donald Trump put it in place by executive order in 2018 after a mass shooting at a Las Vegas concert.

The Pandemic’s Effect: The footprint of gun violence in the United States expanded during the pandemic , as shootings worsened in already suffering neighborhoods and killings spread to new places.

The Emotional Toll: We asked Times readers how the threat of gun violence has affected the way they lead their lives. Here’s what they told us .

- The Highlight

Cops at the schoolyard gate

How the number of police officers in schools skyrocketed in recent decades — and made for a harrowing education for Black and brown youth.

by Kristin Henning

Part of The Schools Issue of The Highlight , our home for ambitious stories that explain our world.

When I was in high school, my school looked like a school. Teachers were in the classrooms. Our principal was in the front office. We had a guidance counselor who helped us think about where to go to college or how to get a job. We had a gym, a basketball court, and a football field.

Today, when I meet my clients at school, I can barely distinguish a school visit from a legal visit to the local youth detention center. At the front door, I am greeted by a phalanx of uniformed police officers, some of whom have guns at their side. In schools, these officers are called school resource officers, or SROs. They are sworn police officers who patrol schools all over the country. In DC, the officers tell me to take everything out of my pockets, put my items in a plastic bin, and run them through a metal detector. I am then instructed to walk through a full-body scanner, and if I wear big jewelry or have metal in my shoes, the officer will “wand” me again with a handheld detector on the other side.

I watch as students all around me are treated the same. There is a lot of banter between the students and the officers — some of it playful, some of it hostile. At one school, an officer tells a child, “You know you’re not supposed to have a cellphone in school. You need to sign that into the front office.” The student lets out a loud sigh and drops the f-word. Another student yells out, “Man, I’m going to be late to class, let me go through.” At least one student is asked to remove his shoes. As I look up, I can see security cameras in the lobby. And when I head to a classroom on the third floor, I am escorted to the elevator by an officer who wants to make sure I am okay. To put it mildly, the schools my clients attend look like prisons at the front door.

I have now been representing children in DC for 25 years, mostly as the director of the Juvenile Justice Clinic at Georgetown Law, where I supervise law students and new attorneys defending children charged with crimes in the city. I also spend a good deal of time traveling, training, and strategizing with juvenile defenders across the country in partnership with the National Juvenile Defender Center.

From the East Coast to the West, from the Deep South to the North, Black children appear in juvenile and criminal courts across the country in numbers that far exceed their presence in the population. Black children are accosted all over the nation for the most ordinary adolescent activities — shopping for prom clothes, playing in the park, listening to music, buying juice from a convenience store, wearing the latest fashion trend, and protesting for their social and political rights.

In DC, our elected attorney general is more attentive now to the harms and disparities impacting people of color, but even with these changes, I have still spent much of the last two decades fighting for Black children who have been arrested and prosecuted for “horseplay” on the Metro, breaking a school window, stealing a pass to a school football game, throwing snowballs (a.k.a. “missiles”) at a passing police car, hurling pebbles across the street at another kid, playing “toss” with a teacher’s hat, and snatching a cellphone from a boyfriend. I have seen Black children handcuffed at ages 9 and 10; 12- and 13-year-old Black boys stopped for riding their bicycles; and industrious 16-and 17-year-old Black youth detained for selling water on the National Mall. The list goes on.

We live in a society that is uniquely afraid of Black children. Americans become anxious — if not outright terrified — at the sight of a Black child ringing the doorbell, riding in a car with white women, or walking too close in a convenience store. Americans think of Black children as predatory, sexually deviant, and immoral. For many, that fear is subconscious, arising out of the historical and contemporary narratives that have been manufactured by politicians, business leaders, and others who have a stake in maintaining the social, economic, and political status quo.

There is something particularly efficient about treating Black children like criminals in adolescence. Black youth are dehumanized, exploited, and even killed to establish the boundaries of whiteness before they reach adulthood and assert their rights and independence. It is no coincidence that Emmett Till was 14 when he was lynched, Trayvon Martin was 17 when he was shot by a volunteer neighborhood watchman, Tamir Rice was 12 when he was shot by the police at a park, Dajerria Becton was 15 when she was slammed to the ground by police at a pool party, and four Black and Latina girls were 12 when they were strip-searched for being “hyper and giddy” in the hallway of their New York middle school.

School resource officers appear in all 50 states. They are visible in both urban meccas and small towns. In 1975, only 1 percent of US schools reported having police stationed on campus. By the 2017–18 school year, 36 percent of elementary schools, 67.6 percent of middle schools, and 72 percent of high schools reported having sworn officers on campus routinely carrying a firearm. In raw numbers, there were 9,400 school resource officers in 1997. By 2016, there were at least 27,000.

Because police operate under many different titles in schools, these numbers are surely low. Tallies often miss private security guards and neighborhood officers assigned by the local police department to patrol several schools without any formal agreement with the school district.

According to a survey of school resource officers in 2018, more than half worked for local police or sheriff’s departments. Twenty percent worked for school police departments, and the remaining worked for some “other” category including the school district, an individual school, school security employers, private companies, and fire departments. Some school systems, like those in Baltimore, Indianapolis, Los Angeles, Miami, Oakland, and Philadelphia, have their own independent police departments. The Los Angeles School Police Department has more than 350 sworn police officers and 125 non-sworn school safety officers.

School resource officers often patrol with guns, batons, Tasers, body cameras, pepper spray, handcuffs, K-9 units, and handheld and full-body metal detectors like those found at an airport. Some are even equipped with military-grade weapons such as tanks, grenade launchers, and M16s.

So what happened to cause such a shift in school culture since I was in high school 35 years ago? For far too long I accepted the simple and often repeated explanation that parents were terrified to send their children to school after the deadly mass shooting at Columbine High School in 1999. Although Columbine certainly played a role in the rapid expansion of school resource officers in the early 21st century, the National Association of School Resource Officers had already formed in 1991, eight years before the tragedy in Colorado. Our nation’s obsession with policing in public schools began long before Columbine. That story began in the mid-20th century, with the fight for — and against — racial desegregation.

Researchers believe the first law enforcement officers appeared in public schools as early as 1939, when the Indianapolis Public Schools hired a “special investigator” to serve the school district from 1939 to 1952.

In 1952, that investigator began to supervise a loosely organized group of police officers who patrolled school property, performed traffic duties, and conducted security checks after hours. The group was reorganized in 1970 to form the Indianapolis School Police. It is significant that the Ku Klux Klan controlled both the state legislature and the Indianapolis Board of School Commissioners from the 1920s through the formation of the early school police force. The Klan had segregated Indianapolis schools by 1927 and kept them that way until the federal government intervened in the 1960s.

Our nation’s obsession with policing in public schools began long before Columbine. That story began in the mid-20th century, with the fight for — and against — racial desegregation.

Other school districts began hiring police in the mid-20th century — more explicitly in response to the evolving racial dynamics in the country. American cities had become more diverse after World War II as Blacks left the Jim Crow South in search of opportunities in industrial centers such as Los Angeles and Flint, Michigan. Whites who were uncomfortable with the exploding populations and shifting demographics blamed the new migrants for emerging social problems such as poverty, racial and ethnic tension, and crime.

Teachers in Flint planted the seed — maybe inadvertently — for a law enforcement presence in schools during a 1953 workshop, when they expressed concerns about growing student enrollments and the potentially negative impacts of overcrowding, including delinquency. Seeking to address these concerns, Flint educators, police, and civic leaders collaborated in 1958 to implement the nation’s first Police-School Liaison Program and ultimately developed the framework for school resource officers as we know them today.

Schools across the country followed Flint’s lead. Programs sprang up in cities including Anchorage, Atlanta, Baton Rouge, Boise, Chicago, Cincinnati, Los Angeles, Miami, Minneapolis, New York City, Oakland, Seattle, and Tucson, on the heels of the US Supreme Court’s 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education to end legal segregation in public schools.

State and local governments sent police into schools under the pretense of protecting Black youth. The real motives, however, likely had more to do with white fear, privilege, and resentment. Municipal leaders in the North and South claimed that Black children lacked discipline and feared they would bring disorder to their schools. In 1957, representatives from the New York City Police Department described Black and Latinx students in low-income neighborhoods as “dangerous delinquents” and “undesirables” capable of “corroding school morale.” Policing in schools also gave school administrators a mechanism for preserving resources for white middle-class students and keeping Black youth in their place.

Tensions escalated the following decade as Black students balked at whites’ opposition to racial equality and schools’ bold refusals to integrate. In cities like Greensboro, North Carolina, and Oklahoma City, students organized protests, walkouts, and marches to demand equal resources and opportunity. Students also insisted on culturally relevant curricula and basic dignity in the classroom.

White, middle-class Americans equated civil rights action with crime and delinquency, inflaming — and sometimes manufacturing — fears of a growing youth crime problem. In this turbulent climate, cities implemented school-police partnerships to combat a “problem” that police and educators explicitly and implicitly blamed on Black and other marginalized youth.

Policing in the schoolhouse grew in lockstep with civil rights protests and gradually became a permanent fixture in integrated schools.

While most school-police partnerships started as local initiatives like the one in Flint, these programs began to draw federal support in 1965 when President Lyndon B. Johnson established the Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice to “inquire into the causes of crime and delinquency” and provide recommendations for prevention. In its 1967 report, the commission predicted that youth would be the greatest threat to public safety in the years to come.

The report drew a tight connection between race, crime, and poverty and frequently reminded readers that “Negroes, who live in disproportionate numbers in slum neighborhoods, account for a disproportionate number of arrests.” The commission referred to young people in racially charged language like “slum children” and “slum youth” from “slum families” and noted that many Americans had already become suspicious of “Negroes” and adolescents they believed to be responsible for crime. The commission’s analysis aligned with television and newspaper reports that stoked fears by depicting civil rights protests as criminal acts instead of political demonstrations against oppression.

Against this backdrop, local and state law enforcement agencies applied for federal grants through the Department of Justice’s newly created Office of Law Enforcement Assistance to fund new crime prevention plans like school-police partnerships.

Concerns about discrimination in school-based policing surfaced almost immediately, including in Flint, the birthplace of the school-police partnership. Notwithstanding initial concerns about delinquency in school, Black teachers and parents began to complain that Flint’s Police-School Liaison Program targeted students of color. As reported in a 1971 review of the initiative, some teachers said the program was “aimed specifically at the black community” and was “anathema to black people” because it enforced “middle class white ethics and mores.”

The race-baiting and fearmongering that motivated the first school-police partnerships during the civil rights era were followed by the mythic lies of the “superpredator” craze in the 1990s. With crime on the rise and the crack epidemic at full throttle by the end of the 1980s, white fears reached epic proportions. State and federal politicians accepted Princeton professor John J. DiIulio Jr.’s highly publicized yet unscientific 1995 predictions of a coming band of Black teenage “superpredators” with reckless abandon, and passed legislation to increase police presence in every aspect of Black adolescent life. Schools were a natural focus.

Congress also passed both the Gun-Free Schools Act and the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act in 1994. The Gun-Free Schools Act was passed to keep drugs, guns, and other weapons out of schools. The Violent Crime Control Act created the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, radically increased federal funding for policing in communities, and laid the foundation for a new wave of federal funding for police in schools.

And then there was Columbine.On April 20, 1999, the nation was rocked by a mass shooting at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado. Two 12th-graders, Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, murdered 12 students and one teacher. Twenty-one additional people were injured by gunshots. Another three were injured trying to escape the school. At the time, it was the deadliest school shooting in US history.

Columbine was the 12th in a spate of school shootings committed by students between 1996 and 1999. These deadly tragedies terrified parents and teachers and prompted increased funding for school safety everywhere. In October 1998, just months before the shooting at Columbine, Congress had already voted to allocate funding for the COPS in Schools grants program.

Days after the shooting, in April 1999, President Bill Clinton promised that the COPS office would release $70 million to fund an additional 600 police officers in schools in 336 communities across the country. In 1998 and 1999, COPS awarded 275 jurisdictions more than $30 million for law enforcement to partner with school systems to address crime and disorder in and around schools. Between 1999 and 2005, COPS in Schools awarded more than $750 million in grants to more than 3,000 law enforcement agencies to hire SROs.

Although these shootings do explain the immediate increase in funding for police in schools, the shootings do not explain the disproportionate surge of police in schools serving mostly Black and Latinx students. Although the vast majority of the school-based shootings in the 1990s — and again in 2012 — occurred in primarily white suburban schools, school resource officers are more likely to be assigned to schools serving mostly students of color.

National data from the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights reveals that youth of color are more likely than white youth to attend schools that employ school police officers. In the 2015–16 school year, 54.1 percent of middle and high schools serving a student body that was at least 75 percent Black had at least one school-based law enforcement or security officer on campus. By contrast, only 32.5 percent of schools serving a student body that was 75 percent or more white had such personnel in place.

The 1990s brought a rapid increase in both school suspensions and school-based arrests as police officers remained confused about their roles on campus and new laws were passed to criminalize normal adolescent behavior. Administrators in the first school-police partnerships viewed school resource officers as part teacher, part counselor, and part law enforcement officer only when necessary.

The partners in Flint hoped to foster a positive relationship between youth and police, prevent youth crime, and provide counseling services for students believed to be at risk of delinquency. As police became more entrenched in schools, students, parents, and civil rights advocates complained that police officers weren’t trained to be counselors and worried about the potential for conflicts of interest when police tried to serve multiple functions. Civil rights groups worried that police were violating students’ rights through unsupervised interrogations, harassment, and surveillance.

Thirty years later, police still haven’t figured out what schools want them to do, and schools haven’t figured out what they want police to do. Only 15 states require schools and law enforcement agencies to develop memoranda of understanding (MOUs) to specify the scope and limits of the officers’ authority on campus. When school districts do have an MOU, they usually focus on the cost-sharing aspects of the agreement and offer few details about when, where, and how police can intervene with students.

Thirty years later, police still haven’t figured out what schools want them to do, and schools haven’t figured out what they want police to do

Even when school resource officers are expressly hired to respond to emergencies and protect students from guns and serious threats of violence, they are quickly drawn into the more routine activities of law enforcement on campus. Forty-one percent of school resource officers surveyed in 2018 reported that “enforcing laws” was their primary role on campus. Police often arrive with little or no training on how their traditional law enforcement roles should differ within the school context and even less training on developmental psychology and adolescent brain development.

A 2013 study found that police academies nationwide spend less than 1 percent of total training hours on juvenile justice topics. In the 2018 survey, roughly 25 percent of school police surveyed indicated that they had no experience with youth before working in schools. Sixty-three percent reported they had never been trained on the teen brain; 61 percent had never been trained on child trauma; and 46 percent had never been trained to work with special education students. Without better training and guidance, police in schools do what they always do. They detain, investigate, interrogate, and arrest. They also intervene with force — sometimes violent and deadly force.

Ultimately, more police in schools means more arrests — three and a half times more arrests than in schools without police. And it means more arrests for minor infractions that teachers and principals used to handle on their own.

When I was in high school in the mid-1980s, we were sent to the principal’s office when we acted out. Sometimes we had to stay after school for detention. I even got suspended once for “play fighting” with one of my classmates, but I was never arrested. Today, children get arrested regularly at school, and mostly for things kids do all the time: fighting or threatening a classmate, breaking a window in anger, vandalism and graffiti, having weed, taking something from someone on a dare, arguing in the hallway when they are supposed to be in class.

Data from across the country mirrors what I see in DC. Although only 7 percent of officers surveyed in 2018 described their duties as “enforcing school discipline,” evidence shows that educators routinely depend on police to handle minor misbehaviors such as disobedience, disrespectful attitudes, disrupting the classroom, and other adolescent behaviors that have little or no impact on school safety. State lawmakers have even passed laws making it a crime to disturb or disrupt the school. As of 2016, at least 22 states and dozens of cities and towns outlaw school disturbances in one way or another.

The Maryland state legislature adopted its “disturbing schools” law back in 1967, shortly after the Baltimore City School District created its school security division. During the 2017–18 school year, 3,167 students were arrested in Maryland’s public schools. About 14 percent of those arrests were for “disruption.” Until May 2018, students in South Carolina could be arrested for disturbing the school if they “loitered about,” “acted in an obnoxious manner,” or “interfered with or disturbed” any student or teacher at school. The penalty was a $1,000 fine and a possible 90-day sentence in jail.

In the 2015-16 academic year, 1,324 students were arrested or cited in the state for disturbing schools, making it the second most common delinquency offense referred to the family court. Black students were almost four times more likely than white youth to be deemed criminally responsible for disturbing schools. South Carolina lawmakers finally eliminated the crime in 2018.

Police in schools are symbolic. They provide an easy answer to fears about violence, guns, and mass shootings. They allow policymakers to demonstrate their commitment to school safety. And for a time, they make teachers and parents “feel” safe. But those who have studied school policing tell us this is a false sense of security.

Schools with school resource officers are not necessarily any safer. An audit from North Carolina, for example, found that middle schools that used state grants to hire and train SROs did not report reductions in serious incidents like assaults, homicides, bomb threats, possession and use of alcohol and drugs, or the possession of weapons.

More from the Schools Issue

And many advocates for police in schools forget that school resource officers were widely criticized for their failures to intervene in the shootings at both Columbine and Parkland. The officer in Columbine followed local protocol at the time and did not pursue the shooters into the building. Many speculated that if he had, there was a good chance the gunmen would not have reached the library, where so many students were targeted. Instead of immediately confronting the threat, school police secured the scene and waited for SWAT teams to arrive.

The sheriff’s deputy who was assigned to Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, also never went in the building, despite an active-shooter policy that instructed deputies to interrupt the shooting and search for victims after a ceasefire. Students later complained that they saw the armed deputy standing outside in a bulletproof vest while school security guards and coaches were running in to shield the students.

Police don’t make students feel safer— at least not Black students in heavily policed communities. To the contrary, police in schools increase psychological trauma, create a hostile learning environment, and expose Black students to physical violence. For students who have already been exposed to police outside school, negative encounters with police in school confirm what their parents and neighbors have told them.

Black students enter their schools to be accosted by the same officers who stop, harass, and even physically assault their family and friends on the street. In much the same way they resent aggressive and racially targeted policing in their communities, students resent inconsistent and unfair school discipline. Black students don’t feel welcome or trusted at school and are less likely than white students to report that school police and security officers have treated them with respect.

For many students, schools have become a literal and figurative extension of the criminal legal system. As schools increasingly rely on police officers to monitor the hallways and control classroom behavior, students feel anxious and alienated by the constant surveillance and fear of police brutality. Over time, students transfer their distrust, resentment, and hostility toward the police to school authorities. Teachers become interchangeable with the police, principals become wardens, and students no longer see school staff as educators, advocates, and protectors.

Black students who feel devalued by unfair disciplinary practices are more likely to withdraw and become delinquent. Policing in schools creates a vicious vortex. Students in heavily policed environments are less likely to be engaged and more likely to drop out. Youth who drop out are more likely to be arrested.

Not only do students feel less safe in school, but they are less safe.

Organizations like the Alliance for Educational Justice have been tracking police assaults in schools across the country for many years. Since 2009, the organization has recorded numerous stories from students of color, as young as 12, who have been hit on the head, choked, punched repeatedly, slammed to the ground, kneed in the back, dragged down the hall, pepper-sprayed while handcuffed, shocked with a stun gun, tased, struck by a metal nightstick, beaten with a baton, and even killed by police at school.

Most recently, in January 2021, 16-year-old Taylor Bracey was knocked unconscious and suffered from headaches, blurry vision, and depression after being body-slammed onto a concrete floor by a school resource officer in Kissimmee, Florida.

Most often, police violence is inflicted in response to nonviolent student behaviors. Students have been physically assaulted for wearing a hat indoors, not tucking in their shirts as required by the dress code, being late to class, going to the bathroom without permission, participating in school demonstrations, fighting in school, having marijuana, being emotionally distraught, cursing at school officials, refusing to give up a cellphone when asked, arguing with a parent on campus, and throwing an orange at the wall.

After Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson, Missouri, investigators from the Department of Justice found that officers in the local school district often used force against students of color for minor disciplinary violations like “peace disturbance” and “failure to comply with instructions.” In one instance, a 15-year-old girl was slammed against a locker and arrested for not following an officer’s orders to go to the principal’s office.

Students of color have characterized policing in schools as a coordinated and intentional effort to control and exclude them. Ironically, proponents of the federally funded COPS in Schools grant program hoped that sending police to schools would improve the image of police generally and increase the level of respect that young people have for the law and the role of law enforcement.

Even Flint’s first school-police partnership was framed as an attempt to “improve community relations between the city’s youth and the local police department.” To date, these efforts have failed. Police in schools remain deeply entrenched in their traditional law enforcement roles and have been unable to dislodge youth’s negative opinions and attitudes about them. The more recent and highly visible incidents of discrimination and brutality against students of color only reinforce historical images of the police as a tool of racial oppression.

Now, 65 years after the Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation in public schools is illegal, Black youth are still systematically denied free, safe, and appropriate education. School segregation is achieved and maintained through school-based arrests and exclusions that deny Black youth access to a high school diploma and all of the opportunities that diploma can provide. In modern America, where formal education is the primary gateway to college, employment, and financial independence, policing in school puts Black youth at a severe disadvantage.

Given how little school-based arrests achieve, current policing strategies can no longer be justified as necessary for school safety. The unnecessary and extreme discipline of Black youth has little to do with the school-based massacres of the 1990s. Columbine can’t explain police involvement in routine school discipline, discriminatory enforcement of school rules, or massive spending on the police infrastructure in American schools. And it certainly can’t explain the violent force that is used to control children of color. It is about time we admit that our infatuation with policing Black children in schools was never about Columbine.

Excerpted from The Rage of Innocence: How America Criminalizes Black Youth by Kristin Henning (Pantheon Books, September 28, 2021).

Kristin Henningis a nationally recognized trainer and consultant on the intersection of race, adolescence, and policing. She is the Blume professor of law and director of the Juvenile Justice Clinic and Initiative at the Georgetown University Law Center; from 1998 to 2001 she was the lead attorney of the Juvenile Unit at the Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia.

Most Popular

Stop setting your thermostat at 72, the lawsuit accusing trump of raping a 13-year-old girl, explained, what the labour party’s big win in the uk will actually mean, leaks about joe biden are coming fast and furious, why is everyone talking about kamala harris and coconut trees, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in The Highlight

The Highlight — The Summer Issue

Hidden from history: Archivists reveal the lives of famous, and not-so-famous, women

Can the world really prevent a bird flu pandemic?

The only child stigma, debunked

Is it possible to be fully authentic?

What AI in music can — and can’t — do

Innovation in child care is coming from a surprising source: Police departments

Why Britain's Conservatives were wiped out by Labour

The little-known but successful model for protecting human and labor rights

Why American politicians are so old

The baffling case of Karen Read

Investigative, data-driven journalism

What you need to know about school policing

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Subscribe and get our journalism delivered directly to your inbox. It’s free.

This story was produced as part of a collaboration with the Center for Public Integrity and USA TODAY .

What is a referral to law enforcement? Does it mean a student was arrested?

A referral occurs when a school employee reports a student to any law enforcement agency or officer, including a school police officer or security staff member for an incident that happens at school, during a school-related event or while taking school transportation, regardless of whether official action is taken.

All arrests are referrals. But not all referrals lead to arrests.

During the 2017-18 school year, nearly 230,000 students were referred to law enforcement across the country. Roughly a quarter of those referrals led to arrests, federal data shows.

The U.S. Department of Education has tweaked the definition of “referral to law enforcement” over time in an effort to include all contact a student may have with officers or security staff that could have negative consequences for the student.

Citations, tickets and court referrals are also considered referrals to law enforcement.

A Center for Public Integrity analysis of U.S. Department of Education data from all 50 states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico found that school policing disproportionately affects students with disabilities, Black children and, in some states, Native American and Latino children.

Despite calls from children’s and civil rights organizations to reduce police presence in schools, these disparities persist. Nationwide, Black students and students with disabilities were referred to law enforcement at nearly twice their share of the overall student population, the Public Integrity analysis found.

What rights do students have when they are referred to law enforcement? Do they have Miranda rights when questioned in connection with a possible crime?

Referrals to law enforcement is such a broad category that it is hard to pinpoint what rights students have. It often depends on the situation, advocates say.

When questioned about an incident that could lead to an arrest, students, in theory, should have the right to refuse to answer questions or provide information to law enforcement or school resource officers. The rules, however, are not always clear on school grounds.

When an officer is based in or assigned to a school, their investigations or interrogations can be viewed differently than those of officers that come in from the outside.

Harold Jordan, the nationwide education equity coordinator for the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania, lays out two different scenarios that could ultimately lead to a student or students being arrested:

In the first, a law enforcement officer walks into a school and informs an administrator, “I’m here to question a student about …” In that situation, known as a custodial interrogation, a student is supposed to be informed of their rights.

In the second scenario, a school resource officer has a conversation where a student discloses something about drug use or possession by themselves or others. Because the student has not been told the officer was investigating something, the student has no reason to suspect it’s an interrogation. But the officer could try to use that information as the basis for an arrest or criminal investigation, Jordan said.

“Even if it’s about somebody else, police will sit you down and ask you a bunch of questions. You don’t automatically know whether you’re the suspect or not,” Jordan said. “So that’s the reason Miranda is important. You have the right to shut up because you have no idea what it is that they’re investigating and how it could be used.”

In 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in J.D.B. v. North Carolina that police and courts must consider a child’s age when determining whether the child should be read Miranda rights. But there is no federal law that requires it and the decision is left to states.

In Kentucky, for example, the state Supreme Court ruled that students must be given Miranda warnings if a law enforcement officer or school resource officer is present when students are questioned about possible criminal conduct.

Criminal is the key word, though. Students accused of committing minor infractions or violating a student code of conduct would not likely have the same rights.

Are schools required to notify parents or guardians when students are referred to law enforcement?

There is no federal requirement for parent notification, even in situations where a student is questioned about an incident that may lead to an arrest. If there is a policy, it is most likely to be set at the district level.

An agreement between the San Franciso Unified School District and the city police department requires school employees to contact a parent or guardian and give them a reasonable opportunity to be present for any police interrogation, unless the child is a suspected victim of child abuse. In their efforts to contact parents or guardians, school officials in that district must use all numbers listed on an emergency card and any additional numbers supplied by the student. If the parent cannot be reached, the school must offer the student the option of having an adult of their choice from the school available during the interrogation.

In Iowa, children under 14 may not waive their Miranda rights without the consent of an adult such as a parent or guardian.

But advocates caution that few districts or states have policies on the books.

How have school districts tried to address concerns about overuse of law enforcement and bias in school policing?

The Des Moines, Iowa, school district ended its partnership with the city police this year. But administrators are not operating under the assumption that taking officers out of schools will eliminate racial disparities in referrals to law enforcement.

Jake Troja, the district’s director of school climate transformation, said that school employees, who initiate many of the referrals, are partly to blame.

“It isn’t that we’re moving away from the use of law enforcement,” Troja said. “We’re still required to call law enforcement for violations of law. But the overuse of law enforcement is not required.”

A common complaint among school resource officers is that they’re called in by teachers and administrators to manage classroom behavior and student discipline, tasks that fall outside the scope of their assigned duties.

Developing policies and agreements between districts and law enforcement agencies that limit or prohibit officer involvement in routine matters can help reduce referrals and arrests, experts say.

When Thomas Traywick Jr. took over as chief of safety and security for schools in Georgia’s Clayton County in 2016, he prohibited officers from arresting students without permission from supervisors. Working alongside Clayton County Chief Juvenile Court Judge Steven Teske, he doubled down on plans to steer students involved in classroom disruption, disorderly conduct and school fights to conflict-resolution workshops instead of court hearings.

At one point, more than 90% of the referrals that came to Teske’s court were those types of cases, he testified before Congress in 2012. Now, “we very seldom ever see a school-related offense,” he said in a recent interview with Public Integrity.

Traywick said he lost officers who complained that the new approach kept them from doing their jobs effectively. But in his second year leading the district police department, referrals to law enforcement decreased 44%, federal data shows. And that was the right outcome, he said.

“We had to change the mindset of the officers,” Traywick said. “We were criminalizing our kids.”

Corey Mitchell is a reporter at the Center for Public Integrity , a nonprofit investigative news organization in Washington, D.C.

Type of Content

News: Based on facts, either observed and verified directly by the reporter, or reported and verified from knowledgeable sources.

Latest stories

Migrant mothers, children living in tents in San Diego amid shelter shortage

Migrants from around the world are among San Diego’s homeless residents, seeking shelter in tents in San Diego parks and public spaces.

Supreme Court says ban on public camping is constitutional; San Diego leaders react

More complaints surface after hoover high associate principal arrested on pornography charges, congressman requests millions in federal funds to upgrade san diego’s flood-prone storm drains.

We've recently sent you an authentication link. Please, check your inbox!

Sign in with a password below, or sign in using your email .

Get a code sent to your email to sign in, or sign in using a password .

Enter the code you received via email to sign in, or sign in using a password .

Subscribe to our newsletters:

- Latest news An email alert for every new story.

- The Weekender A weekly email to start the weekend, sent Fridays.

Sign in with your email

Lost your password?

Try a different email

Send another code

Sign in with a password

Read our privacy policy here.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Inside The National Movement To Push Police Out Of Schools

Anya Kamenetz

Police presence in schools has been growing for decades; now there's a national movement to get them out.

Copyright © 2020 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Why Do We Have Cops in Schools?

In the mid-1970s, police officers were in only about 1 percent of US schools. That changed since the late 1990s.

In the weeks since the police murder of George Floyd, school districts across the country have cut ties with police departments. The shift has the potential to reverse a trend that’s lasted more than two decades, as law enforcement has become increasingly intertwined with education. In 2018, Joshua P. Starr, CEO of education organization PDK International, described what that looked like firsthand . He’s a former superintendent of school districts in Montgomery County, Maryland and Stamford, Connecticut.

Starr writes that the federal School Resource Officer (SRO) program, which pays for part of the cost of stationing officers in schools, started in the 1950s but didn’t catch on for a long time. In the mid-1970s, police officers were in only about 1 percent of US schools. That changed since the late 1990s, as school shooting incidents brought a wave of concern about safety. Today, 60 percent of schools have a police presence.

And, at least until recently, SROs were hugely popular. In a 2018 poll, Starr writes, 80 percent of parents favored posting armed police officers at their child’s school. That made superintendents like him cautious about airing “even the mildest criticism” of SROs,” he writes. “Privately, though, many district leaders will tell you that if they had a choice, they’d rather not have armed officers in the schools at all.” School administrators may have little control over the hiring or management of SROs.

“I’ve seen cases where students got into a fight and the principal responded by offering conflict resolution, only to learn that the SRO decided to charge the participants with a crime,” Starr writes.

In cases across the country, legal writer Stephanie Francis Ward writes, SROs have arrested students over offences as mild as flatulence or dress code violations . She describes one incident in Raleigh, North Carolina in which a student, who had been diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder, cut in front of another student in the lunch line.

“A school resource officer reportedly grabbed the boy, 16, by the arm,” they write. “They boy pulled away, and the officer pulled his arm behind his back and handcuffed him in front of other students.”

The boy was suspended for three days. Upon his return to school, the legal complaint alleged, a group of students assaulted him, and the SRO responded by shooting pepper spray in his face while he was on the ground.

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

Starr and some education officials Ward spoke with advocated for ways to improve SROs, like helping them learn more about child development and having clear agreements between schools and police departments. But others argued for completely replacing the law-enforcement model. For example, in one Chicago school, Mariame Kaba, an educator and prominent advocate of police and prison abolition, helped create a “peace room.” Rather than punish students for misbehavior, teachers could recommend that they visit the room and work with volunteers trained in restorative justice techniques.

With municipal policies and public opinion on policing in flux, that could be a model more schools will investigate.

Editor’s note: This story originally stated that George Floyd’s death was a police shooting. Floyd died after a police offer knelt on his neck for over eight minutes.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

The Coldest Cream

Wooden Kings and Winds of Change in Tonga

The Impact JSTOR in Prison Has Made on Me

Sex (No!), Drugs (No!), and Rock and Roll (Yes!)

Recent posts.

- Black Freedom and Indian Independence

- Real Estate and the Revolution

- Birthing the Jersey Devil

- Celebrating the Fourth of July

- Swimming Rediscovered, True Crime, and Zealandia

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

How charges against 2 Uvalde school police officers are still leaving some families frustrated

This combo of booking images provided by Uvalde County, Texas, Sheriff’s Office, shows Pete Arredondo, left, the former police chief for schools in Uvalde, Texas, and Adrian Gonzales, a former police officer for schools in Uvalde, Texas, Both men were arrested and booked into jail before they were released on charges related to the May 24, 2022, attack that killed 19 children and two teachers at at Robb Elementary. (Uvalde County Sheriff’s Office via AP)

FILE - Uvalde School Police Chief Pete Arredondo, third from left, stands during a news conference outside of the Robb Elementary school on May 26, 2022, in Uvalde, Texas. Arredondo was arrested and briefly booked into the Uvalde County jail before he was released Thursday, June 27, 2024, on 10 state jail felony counts of abandoning or endangering a child in the May 24, 2022, attack that killed 19 children and two teachers. (AP Photo/Dario Lopez-Mills, File)

This photo provided by Uvalde County Sheriff’s Office shows Pete Arredondo. Arredondo, the former police chief for schools in Uvalde, Texas, was arrested and briefly booked into ail before he was released Thursday, June 27, 2024, on 10 state jail felony counts of abandoning or endangering a child in the May 24, 2022, attack that killed 19 children and two teachers.(Uvalde County Sheriff’s Office via AP)

Esta fotografía proporcionada por el Departamento de Policía del condado de Uvalde muestra a Pete Arredondo. El exjefe de la policía escolar de Uvalde, Texas, fue arrestado y fichado en la prisión del condado el jueves 27 de junio de 2024. (Departamento de Policía del condado de Uvalde vía AP)

- Copy Link copied

AUSTIN, Texas (AP) — Two indictments against former Uvalde, Texas, schools police officers are the first charges brought against law enforcement for the botched response that saw hundreds of officers wait more than an hour to confront an 18-year-old gunman who killed 19 fourth-grade students and two teachers at Robb Elementary.

For some Uvalde families, who have spent the last two years demanding police accountability, the indictments brought a mix of relief and frustration. Several wonder why more officers have not been charged for waiting to go into the classroom, where some victims lay dying or begging for assistance, to help bring a quicker end to one of the worst school shootings in U.S. history.

Former Uvalde schools police Chief Pete Arredondo and former Officer Adrian Gonzales were indicted on June 26 by a Uvalde County grand jury on multiple counts of child endangerment and abandonment over their actions and failure to immediately confront the shooter. They were among the first of nearly 400 federal, state and local officers who converged on the school that day.

“I want every single person who was in the hallway charged for failure to protect the most innocent,” said Velma Duran, whose sister Irma Garcia was one of the teachers killed. “My sister put her body in front of those children to protect them, something they could have done. They had the means and the tools to do it. My sister had her body.”

Uvalde County District Attorney Christina Mitchell has not said if any other officers will be charged or if the grand jury’s work is done.

Here are some things to know about the criminal investigation into the police response:

The Shooting

The gunman stormed into the school on May 24, 2022 and killed his victims in two classrooms.

More than 370 officers responded but waited more than 70 minutes to confront the shooter, even as he could be heard firing an AR-15-style rifle.

Terrified students inside the classrooms called 911 as agonized parents begged for intervention by officers, some of whom could hear shots being fired while they stood in a hallway. A tactical team of officers eventually went into the classroom and killed the shooter.

Scathing state and federal investigative reports on the police response have catalogued “cascading failures” in training, communication, leadership and technology problems.

The Charges

The indictment against Arredondo , who was the on-site commander at the shooting , accused the chief of delaying the police response despite hearing shots fired and being notified that injured children were in the classrooms and a teacher had been shot.

Arredondo called for a SWAT team, ordered the initial responding officers to leave the building and attempted to negotiate with the 18-year-old gunman, the indictment said. The grand jury said it considered his actions criminal negligence.

Gonzales was accused of abandoning his training and not confronting the shooter, even after hearing gunshots as he stood in a hallway.

All the charges are state jail felonies that carry up to two years in jail if convicted.

Arredondo said in a 2022 interview with the Texas Tribune that he tried to “eliminate any threats, and protect the students and staff.” Gonzalez’s lawyer on Friday called the charges “unprecedented in the state of Texas” and said the officer believes he did not break any laws or school district policy.

The first U.S. law enforcement officer ever tried for allegedly failing to act during an on-campus shooting was a campus sheriff’s deputy in Florida who didn’t go into the classroom building and confront the perpetrator of the 2018 Parkland massacre. The deputy, who was fired, was acquitted of felony neglect last year. A lawsuit by the victims’ families and survivors is pending.

The Lawsuits

The families are pursing accountability from authorities in other state and federal courts. Several have filed multiple civil lawsuits.

Two days before the two-year anniversary of the shooting, the families of 19 victims filed a $500 million lawsuit against nearly 100 state police officers who were part of the botched response. The lawsuit accuses the troopers of not following their active shooter training and not confronting the shooter. The highest ranking Department of Public Safety official named as a defendant is South Texas Regional Director Victor Escalon.

The same families also reached a $2 million settlement with the city under which city leaders promised higher standards for hiring and training local police.

On May 24, a group of families sued Meta Platforms , which owns Instagram, and the maker of the video game Call of Duty over claims the companies bear responsibility for the weapons used by the teenage gunman.

They also filed another lawsuit against gun maker Daniel Defense, which made the AR-style rifle used by the gunman.

Family of 13-year-old fatally shot by Utica police says he never forgot to say ‘I love you’

Nyah Mway’s mother, Chee War, remembers about seven years ago when he told her he wanted to name his baby sister himself.

“‘Paw K War,’” Chee War, 39, said, explaining that the name means “blooming flower.” “We didn’t even know how he got that name.”

From then on, Nyah Mway — the 13-year-old boy who was fatally shot by police in Utica, New York, on Friday — was fiercely protective of his sister. He was protective of his whole family, in fact.

He’s being remembered as a doting sibling and son.

“Whenever he comes back from school, he’ll say, ‘I love you,’” Chee War said.

The people of Myanmar do not customarily have surnames, instead taking individual compound names.

Nyah Mway was tackled to the ground and shot after he ran from police, who said he was one of two youths stopped in connection with an armed robbery investigation. Authorities said he appeared to have a weapon in his hand, which turned out to be a replica of a Glock 17 Gen 5 handgun with a detachable magazine.

Utica police has identified Patrick Husnay as the officer who fired his weapon at the teen. Officers Bryce Patterson and Andrew Citriniti were also involved in the incident. All three are on paid administrative leave under department policy, officials said.

Investigations have been launched by the police department and the State attorney general’s Special Investigations Office. In an email, Utica Police Lt. Michael Curley did not comment on the probes but said that through the process, “the facts of the incident will be made available for the public to see.”

“We will continue to be transparent and open with the investigative process to rebuild the trust within our local community,” he said.

Nyah Mway, a refugee who had fled to the U.S. from Myanmar with his family when he was 4, had just finished eighth grade and was looking forward to starting high school in the fall, his family said. His mother said that like any other teenager, he loved spending time playing with his friends. But Nyah Mway, whom she described as “obedient and respectful,” had a particularly close relationship with his family.

After his sister was born, Chee War said, Nyah Mway took on a protector role, making sure she was not out too late, helping her mind her manners and pitching in with homework help.

Thuong Oo, Nyah Mway’s older brother, also said he had a loving relationship with his two older siblings, acting not only as a video game buddy at times but also as a source of wisdom.

“He always had advice for me when I asked him,” Thuong Oo said. “He would talk to me, like, ‘Do you need help? Do you need anything?’ He always talked to me in a calm voice.”

Without Nyah Mway, a soothing force in his life, things feel different, Thuong Oo said, adding that their 16-year-old brother, Maung Zaw Myint, has been “traumatized.”

“I just can’t think right now. Some of the time, people come talk to me,” he said. “I act like I’m all right but I’m not.”

Thuong Oo said the family came to the U.S. looking for a better life. Their ethnic group, the Karens, are among those who are warring with the military rulers of the Southeast Asian country of Myanmar. After having resettled in New York, Nyah Mway had big plans, his family said.

“He always told me that he wanted to keep going to school. He wanted to make my parents proud,” Thuong Oo said through tears. “He wanted to see me and my brother graduate from high school and go to college and have a degree and everything. He wanted to be a doctor when he grew up.”

But the family are now unsure of their safety in the U.S.

“Police are supposed to be protectors,” Thuong Oo said. “If they really did that, then how can we trust the police?”

The family did not go into detail about their thoughts on the investigation. Earl Ward and Julia Kuan, their attorneys, said in a statement that they are seeking accountability from the officers.

“As this family grieves the loss of their 13 year old child, they simply want to know why? Why was Nyah Mway shot and killed when he was held down by officers and posed no threat?” the attorneys said. “No one has answered that question. The family and the community deserve an answer. And not next week, not tomorrow but now.”

Thuong Oo captured his thoughts in a poem he dedicated to his brother.

“Love is love,” he wrote in the opening line. “But a brother’s love will never be gone.”

For more from NBC Asian America, sign up for our weekly newsletter .

Kimmy Yam is a reporter for NBC Asian America.

- Our Mission

- Our Sponsors

- Editorial Independence

- Write for The Crime Report

- Center on Media, Crime & Justice at John Jay College

- Journalists’ Conferences

- John Jay Prizes/Awards

- Stories from Our Network

- TCR Special Reports

- Research & Analysis

- Crime and Justice News

- At the Crossroads

- Domestic Violence

- Juvenile Justice

- Case Studies and Year-End Reports

- Media Studies

- Subscriber Account

The School That Calls the Police on Students Every Other Day

This story was originally published by ProPublica . ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox .

On the last street before leaving Jacksonville, there’s a dark brick one-story building that the locals know as the school for “bad” kids. It’s actually a tiny public school for children with disabilities. It sits across the street from farmland and is 2 miles from the Illinois city’s police department, which makes for a short trip when the school calls 911.

Administrators at the Garrison School call the police to report student misbehavior every other school day, on average. And because staff members regularly press charges against the children — some as young as 9 — officers have arrested students more than 100 times in the last five school years, an investigation by the Chicago Tribune and ProPublica found. That is an astounding number given that Garrison, the only school that is part of the Four Rivers Special Education District, has fewer than 65 students in most years.

No other school district — not just in Illinois, but in the entire country — had a higher student arrest rate than Four Rivers the last time data was collected nationwide. That school year, 2017-18, more than half of all Garrison students were arrested.

Officers typically handcuff students and take them to the police station, where they are fingerprinted, photographed and placed in a holding room. For at least a decade, the local newspaper has included the arrests in its daily police blotter for all to see.

The students enrolled each year at Garrison have severe emotional or behavioral disabilities that kept them from succeeding at previous schools. Some also have been diagnosed with autism, ADHD or other disorders. Many have experienced horrifying trauma, including sexual abuse, the death of parents and incarceration of family members, according to interviews with families and school employees.

Getting arrested for behavior at school is not inevitable for students with such challenges. There are about 60 similar public special education schools across Illinois, but none comes anywhere close to Garrison in their number of student arrests, the investigation found.

The ProPublica-Tribune investigation — built on hundreds of school reports and police records, as well as dozens of interviews with employees, students and parents — reveals how a public school intended to be a therapeutic option for students with severe emotional disabilities has instead subjected many of them to the justice system.

It is “just backwards if you are sending kids to a therapeutic day school and then locking them up. That is not what therapeutic day schools are for,” said Jessica Gingold, an attorney in the special education clinic at Equip for Equality, the state’s federally appointed watchdog for people with disabilities.

“If the school exists for young people who need support, to think of them as delinquents is basically the worst you could do. It’s counter to what should be happening,” Gingold said.

Because of the difficulties the students face in regulating their emotions, these specialized schools are tasked with recognizing what triggers their behavior, teaching calming strategies and reinforcing good behavior. But Garrison doesn’t even offer students the type of help many traditional schools have: a curriculum known as social emotional learning that is aimed at teaching students how to develop social skills, manage their emotions and show empathy toward others.

Tracey Fair, director of the Four Rivers Special Education District, said it is the only public school in this part of west central Illinois for students with severe behavioral disabilities, and there are few options for private placement. School workers deal with challenging behavior from Garrison students every day, she said.

“There are consequences to their behavior and this behavior would not be tolerated anywhere else in the community,” Fair said in written answers to reporters’ questions.

Fair, who has overseen Four Rivers since July 2020, said Garrison administrators call police only when students are being physically aggressive or in response to “ongoing” misbehavior. But records detail multiple instances when staff called police because students were being disobedient: spraying water, punching a desk or damaging a filing cabinet, for example.

“The students were still not calming down, so police arrested them,” wrote Fair, speaking on behalf of the district and the school.

This year, the Tribune and ProPublica have been exposing the consequences for students when their schools use police as disciplinarians. The investigation “The Price Kids Pay” uncovered the practice of Illinois schools working with local law enforcement to ticket students for minor misbehavior. Reporters documented nearly 12,000 tickets in dozens of school districts, and state officials moved quickly to denounce the practice .

This latest investigation further reveals the harm to children when schools abdicate student discipline to police. Arrested students miss time in the classroom and get entangled in the justice system. They come to view adults as hostile and school as prison-like, a place where they regularly are confined to classrooms when the school is “on restriction” because of police presence.

U.S. Department of Education and Illinois officials have reminded educators in recent months that if school officials fail to consider whether a student’s behavior is related to their disability, they risk running afoul of federal law.

But unlike some other states, Illinois does not require schools to report student arrest data to the state or direct its education department to monitor police involvement in school incidents. Legislative efforts to do so have stalled over the past few years.

In response to questions from reporters about Garrison, Illinois Superintendent of Education Carmen Ayala said the frequent arrests there were “concerning.” An Illinois State Board of Education spokesperson said a state team visited the school this month to examine “potential violations” raised through ProPublica and Tribune reporting.

The team confirmed an overreliance on police and, as a result, the state will provide training and other professional development, spokesperson Jackie Matthews said.

“It is not illegal to call the police, but there are tactics and strategies to use to keep it from getting to that point,” Matthews said.

Ayala said educators cannot ignore their responsibility to help students work through behavioral issues.

“Involving the police in any student issue can escalate the situation and lead to criminal justice involvement, so calling the police should be a last resort,” she said in a written statement.

In 2018, Jacksonville police arrested a student named Christian just a few weeks into his first year at Garrison, when he was 12 years old. His “disruptive” behavior earlier in the day — he had knocked on doors and bounced a ball in the hallway — had led to a warning: “One more thing” and he would be arrested, a school report said. He then removed items from an aide’s desk and was “being disrespectful,” so police were summoned. They took him into custody for disorderly conduct.

Christian has attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. Now 16, he has been arrested at Garrison several more times and was sent to a detention center after at least one of the arrests, he and his mother said.

He stopped going to school in October; his mother said it’s heartbreaking that he’s not in class, but at Garrison, “it’s more hectic than productive. He’s more in trouble than learning anything.”

“If they call the police on you, you are going to jail,” Christian told reporters. “It is not just one coming to get you. It will be two or three of them. They handcuff you and walk you out, right out the door.”

Handcuffs and Holding Rooms

Just over an hour into the school day on Nov. 15, two police cars rushed into the Garrison school parking lot and stopped outside the front doors. Three more squad cars pulled in behind them but quickly moved on.

Principal Denise Waggener had called the Jacksonville police to report that a 14-year-old student had been spitting at staff members. When police arrived, one of the officers recognized the boy, because he had driven him to school that morning. The student had missed the bus and called police for help, according to a police report and 911 call.

School staff had placed the boy in one of Garrison’s small cinder-block seclusion rooms for “misbehavior,” police records show. A school worker told the officer she had been standing in the doorway of the seclusion room when the boy spit and it landed on her face, glasses and shirt.

The child “initially stated he did not spit at anyone, but then said he did spit,” according to the police report, “but instantly regretted doing so.” The report said the child “stated he knew right from wrong, but often had violent outbursts.”

The worker asked to press charges, and the officer arrested the boy for aggravated battery.

One officer told the child he was under arrest while another searched and handcuffed him. They put him in the back seat of a squad car, drove him to the police station, read him his rights and booked him. Officers told the boy the county’s probation department would contact him later, and then they dropped him off with a guardian, records show.

The Tribune and ProPublica documented and analyzed 415 of Garrison’s “police incident reports” dating to 2015 and found the school has called police, on average, once every two school days.

The reports, written by school staff and obtained through public records requests, describe in detail what happened up until the moment police were called. These narratives, along with recordings of 911 calls, show that school workers often summon police not amid an emergency but because someone at the school wants police to hold the child responsible for their behavior.