What is cultural tourism and why is it growing?

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

Cultural tourism is big business. Some people seek to embark on their travels with the sole intention of having a ‘cultural’ experience, whereas others may experience culture as a byproduct of their trip. We can argue that there is some form of cultural tourism in most holidays (even when taking an all-inclusive holiday you might try to local beer, for example).

But what do we mean by the term ‘cultural tourism’? What’s it all about? In this post I will explain what is meant by the term cultural tourism, providing a range of academic definitions. I will also explain what the different types of cultural tourists are, give examples of cultural tourism activities and discuss the impacts of cultural tourism. Lastly, I will provide a brief summary of some popular cultural tourism destinations.

What is cultural tourism?

Cultural tourism is the act of travellers visiting particular destinations in order to experience and learn about a particular culture . This can include many activities such as; attending events and festivals, visiting museums and tasting the local food and drinks.

Cultural tourism can also be an unintentional part of the tourism experience, whereby cultural immersion (with the local people, their language, customs, cuisine etc) is an inevitable part of a person’s holiday.

Cultural tourism definitions

It has been suggested that tourism is the ideal arena in which to investigate the nature of cultural production (MacCannell, 1976). Tourism provides endless opportunities to learn about the way other people live, about their society and their traditions. Whether you are attending the Running of the Bulls Festival in Pamplona , visiting the pyramids in ancient Egypt , taking a tour of the tea plantations in China or enjoying the locally brewed Ouzo on your all-inclusive holiday to Greece, you will inevitably encounter some form of cultural tourism as part of your holiday experience.

The World Tourism Organisation (WTO) (1985) broadly define cultural tourism as the movements of persons who satisfy the human need for diversity, tending to raise the cultural level of the individual and giving rise to new knowledge, experience and encounters. Cultural tourism is commonly associated with education in this way, some describing it more narrowly as educational cultural tourism (e.g. Bualis and Costa, 2006; Harner and Swarbrooke, 2007; Richards, 2005).

Although a common, more specific definition has not been agreed amongst academics due to the complexity and subjectivity of the term, there do appear to be two distinct viewpoints. The first focusses upon the consumption of cultural products such as sites or monuments (Bonink, 1992; Munsters, 1994), and the second comprises all aspects of travel, where travellers learn about the history and heritage of others or about their contemporary ways of life or thought (MacIntosh and Goeldner, 1986).

Csapo (2012) pertains that the umbrella term of cultural tourism can encompass a number of tourism forms including heritage (material e.g. historic buildings and non-material e.g. literature, arts), cultural thematic routes (e.g. spiritual, gastronomic, linguistic), cultural city tourism, traditions/ethnic tourism, events and festivals, religious tourism and creative culture (e.g. performing arts, crafts).

Types of cultural tourists

In attempt to understand the scope of cultural tourism academics have developed a number of typologies, usually based upon the tourist’s level of motivation.

Bywater (1993) differentiated tourists according to whether they were culturally interested, motivated or inspired.

Culturally interested tourists demonstrate a general interest in culture and consume cultural attractions casually as part of a holiday rather than consciously planning to do so.

Culturally motivated tourists consume culture as a major part of their trip, but do not choose their destination on the basis of specific cultural experiences, whereas for culturally inspired tourists culture is the main goal of their holiday.

A more complex typology was proposed by McKercher and Du Cros (2002), who defined tourists based upon the depth of the cultural experience sought, distinguishing them in to one of five hierarchical categories.

The first is the purposeful cultural tourist for whom cultural tourism is their primary motive for travel. These tourists have a very deep cultural experience.

The second category is the sightseeing cultural tourist for whom cultural tourism is a primary reason for visiting a destination, but the experience is more shallow in nature.

The serendipitous cultural tourist does not travel for cultural reasons, but who, after participating, ends up having a deep cultural tourism experience, whilst the casual cultural tourist is weakly motivated by culture and subsequently has a shallow experience.

Lastly, the incidental cultural tourist is one who does not travel for cultural tourism reasons but nonetheless participates in some activities and has shallow experiences.

Adapting this theory, Petroman et al (2013) segments tourists based upon their preferred cultural activities.

The purposeful cultural tourist, described as according to Mckercher and Du Cros (2002), enjoys learning experiences that challenge them intellectually and visits history museums, art galleries, temples and heritage sites that are less known.

The tour-amateur cultural tourist is akin with the sightseeing cultural tourist above and they often travel long distances, visit remote areas, enjoy tours and wandering through the streets.

The occasional cultural tourist plays a moderate role in the decision of travelling and enjoys an insignificant cultural experience, their preferred activities being to visit attractions and temples that are easy to reach and to explore, although not to the extent that the tour-amateur cultural tourist does.

The incidental cultural tourist plays a small or no role in the decision to travel and enjoys an insignificant cultural experience, whilst visiting attractions that area within easy reach and heritage theme parks.

The last segment is the accidental cultural tourist, who plays a small or no role in the decision to travel but enjoys a deep cultural experience. This tourist type is diverse and as such has no preferred activities attributed to it.

Importance of cultural tourism

Cultural tourism is important for many reasons. Perhaps the most prominent reason is the social impact that it brings.

Cultural tourism can help reinforce identities, enhance cross cultural understanding and preserve the heritage and culture of an area. I have discussed these advantages at length in my post The Social Impacts of Tourism , so you may want to head over there for more detail.

Cultural tourism can also have positive economic impacts . Tourists who visit an area to learn more about a culture or who visit cultural tourism attraction, such as museums or shows, during their trip help to contribute to the economy of the area. Attractions must be staffed, bringing with it employment prospects and tertiary businesses can also benefit, such as restaurants, taxi firms and hotels.

Furthermore, for those seeking a deep cultural experience, options such as homestays can have positive economic benefits to the members of the community who host the tourists.

Read also: Overtourism explained: What, why and where

Personally, I think that one of the most important benefits of cultural tourism is the educational aspect. Tourists and hosts alike can learn more about different ways of life. This can help to broaden one’s mind, it can help one to think differently and to be more objective. These are qualities that can have many positive effects on a person and which can contribute to making them more employable in the future.

Cultural tourism activities

Whether a tourist is seeking a deep cultural experience or otherwise, there are a wide range of activities that can be classified as cultural tourism. Here are a few examples:

- Staying with a local family in a homestay

- Having a tour around a village or town

- Learning about local employment, for example through a tour of a tea plantation or factory

- Undertaking volunteer work in the local community

- Taking a course such as cooking, art, embroidery etc

- Visiting a museum

- Visiting a religious building, such as a Mosque

- Socialising with members of the local community

- Visiting a local market or shopping area

- Trying the local food and drink

- Going to a cultural show or performance

- Visiting historic monuments

Impacts of cultural tourism

There are a range of impacts resulting from cultural tourism activities, both good and bad. Here are some of the most common examples:

Positive impacts of cultural tourism

Revitalisation of culture and art.

Some destinations will encourage local cultures and arts to be revitalised. This may be in the form of museum exhibitions, in the way that restaurants and shops are decorated and in the entertainment on offer, for example.

This may help promote traditions that may have become distant.

Preservation of Heritage

Many tourists will visit the destination especially to see its local heritage. It is for this reason that many destinations will make every effort to preserve its heritage.

This could include putting restrictions in place or limiting tourist numbers, if necessary. This is often an example of careful tourism planning and sustainable tourism management.

This text by Hyung You Park explains the principles of heritage tourism in more detail.

Negative impacts of cultural tourism

Social change.

Social change is basically referring to changes in the way that society acts or behaves. Unfortunately, there are many changes that come about as a result of tourism that are not desirable.

There are many examples throughout the world where local populations have changed because of tourism. Perhaps they have changed the way that they speak or the way that they dress. Perhaps they have been introduced to alcohol through the tourism industry or they have become resentful of rich tourists and turned to crime. These are just a few examples of the negative social impacts of tourism.

Read also: Business tourism explained: What, why and where

Globalisation and the destruction of preservation and heritage.

Globalisation is the way in which the world is becoming increasingly connected. We are losing our individuality and gaining a sense of ‘global being’, whereby we more and more alike than ever before.

Globalisation is inevitable in the tourism industry because of the interaction between tourists and hosts, which typically come from different geographic and cultural backgrounds. It is this interaction that encourage us to become more alike.

Standardisation and Commercialisation

Similarly, destinations risk standardisation in the process of satisfying tourists’ desires for familiar facilities and experiences.

While landscape, accommodation, food and drinks, etc., must meet the tourists’ desire for the new and unfamiliar, they must at the same time not be too new or strange because few tourists are actually looking for completely new things (think again about the toilet example I have previously).

Tourists often look for recognisable facilities in an unfamiliar environment, like well-known fast-food restaurants and hotel chains. Tourist like some things to be standardised (the toilet, their breakfast, their drinks, the language spoken etc), but others to be different (dinner options, music, weather, tourist attractions etc).

Loss of Authenticity

Along similar lines to globalisation is the loss of authenticity that often results from tourism.

Authenticity is essentially something that is original or unchanged. It is not fake or reproduced in any way.

The Western world believe that a tourist destination is no longer authentic when their cultural values and traditions change. But I would argue is this not natural? Is culture suppose to stay the same or it suppose to evolve throughout each generation?

Take a look at the likes of the long neck tribe in Thailand or the Maasai Tribe in Africa. These are two examples of cultures which have remained ‘unchanged’ for the sole purpose of tourism. They appear not to have changed the way that they dress, they way that they speak or the way that they act in generations, all for the purpose of tourism.

You can learn more about what is authenticity in tourism here or see some examples of staged authenticity in this post.

Culture clashes

Because tourism involves movement of people to different geographical locations cultural clashes can take place as a result of differences in cultures, ethnic and religious groups, values, lifestyles, languages and levels of prosperity.

Read also: Environmental impacts of tourism

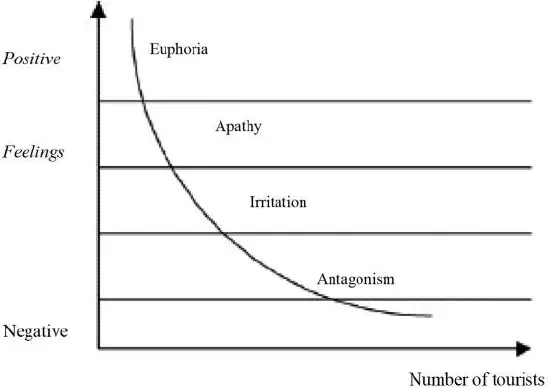

The attitude of local residents towards tourism development may unfold through the stages of euphoria, where visitors are very welcome, through apathy, irritation and potentially antagonism when anti-tourist attitudes begin to grow among local people. This is represented in Doxey’s Irritation Index, as shown below.

Tourist-host relationships

Culture clashes can also be exasperated by the fundamental differences in culture between the hosts and the tourists.

There is likely to be economic inequality between locals and tourists who are spending more than they usually do at home. This can cause resentment from the hosts towards the tourists, particularly when they see them wearing expensive jewellery or using plush cameras etc that they know they can’t afford themselves.

Further to this, tourists often, out of ignorance or carelessness, fail to respect local customs and moral values.

There are many examples of ways that tourists offend the local population , often unintentionally. Did you know that you should never put your back to a Buddha? Or show the sole of your feet to a Thai person? Or show romantic affection in public in the Middle East?

Cultural tourism destinations

Whilst many would argue that cultural tourism is ingrained to some extent in travel to any country, there are some particular destinations that are well-known for their ability to provide tourists with a cultural experience.

Cultural tourism in India

It is impossible not to visit India and experience the culture. Even if you are staying in a 5 star Western all-inclusive hotel in Goa, you will still test Indian curries, be spoken to by Indian workers and see life outside of the hotel on your transfer to and from the airport.

For most people who travel to India, however, cultural tourism is far more than peeking outside of the enclave tourism bubble of their all-inclusive hotel.

Thousands of international tourists visit the Taj Mahal each year. Many more people visit the various Hindu and Buddhist temples scattered throughout the country as well as the various Mosques. Some visit the famous Varanassi to learn about reincarnation.

Most tourists who visit India will try the local dal, eat the fresh mutton and taste chai.

All of these activities are popular cultural tourism activities.

Cultural tourism in Thailand

Thailand is another destination that offers great cultural tourism potential. From the Buddhist temples and monuments and the yoga retreats to homestays and village tours, there are ample cultural tourism opportunities in Thailand .

Cultural tourism in Israel

Israel is popular with religious tourists and those who are taking a religious pilgrimage, as well as leisure tourists. I visited Israel and loved travelling around to see the various sights, from Bethlehem to Jerusalem . I’m not religious in any way, but I loved learning about the history, traditions and cultures.

Cultural tourism in New York

New York is a city that is bustling with culture. It is world famous for its museums and you can learn about anything from World War Two to the Twin Towers here.

Many would argue that shopping is ingrained in the culture of those who live in New York and many tourists will take advantage of the wide selection of products on offer and bargains to be had on their travels to New York.

You can also treat yourself to watching a traditional West End show, trying some of the famous New York Cheesecake and enjoying a cocktail in Times Square!

Cultural tourism in Dubai

Dubai might not be the first destination that comes to mind when you think of cultural tourism, but it does, in fact, have a great offering.

What I find particular intriguing about Dubai is the mix of old and new. One minute you can be exploring the glitz and glamour of the many high-end shopping malls and skyscrapers and the next you can be walking through a traditional Arabian souk.

Cultural tourism: Conclusion

As you can see, there is big business in cultural tourism. With a wide range of types of cultural tourists and types of cultural tourism experiences, this is a tourism sector that has remarkable potential. However, as always, it is imperative to ensure that sustainable tourism practices are utilised to mitigate any negative impacts of cultural tourism.

If you are interested in learning more about topics such as this subscribe to my newsletter ! I send out travel tips, discount coupons and some material designed to get you thinking about the wider impacts of the tourism industry (like this post)- perfect for any tourism student or keen traveller!

Further reading

Want to learn more about cultural tourism? See my recommended reading list below.

- Cultural Tourism – A textbook illustrating how heritage and tourism goals can be integrated in a management and marketing framework to produce sustainable cultural tourism.

- Deconstructing Travel: Cultural Perspectives on Tourism – This book provides an easily understood framework of the relationship between travel and culture in our rapidly changing postmodern, postcolonial world.

- Re-Investing Authenticity: Tourism, Place and Emotions – This ground-breaking book re-thinks and re-invests in the notion of authenticity as a surplus of experiential meaning and feeling that derives from what we do at/in places.

- The Business of Tourism Management – an introduction to key aspects of tourism, and to the practice of managing a tourism business.

- Managing Sustainable Tourism – tackles the tough issues of tourism such as negative environmental impact and cultural degradation, and provides answers that don’t sacrifice positive economic growth.

- Tourism Management: An Introduction – An introductory text that gives its reader a strong understanding of the dimensions of tourism, the industries of which it is comprised, the issues that affect its success, and the management of its impact on destination economies, environments and communities.

- Responsible Tourism: Using tourism for sustainable development – A textbook about the globally vital necessity of realising sustainable tourism.

Liked this article? Click to share!

UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

Ethics, Culture and Social Responsibility

- Global Code of Ethics for Tourism

- Accessible Tourism

Tourism and Culture

- Women’s Empowerment and Tourism

share this content

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

The convergence between tourism and culture, and the increasing interest of visitors in cultural experiences, bring unique opportunities but also complex challenges for the tourism sector.

“Tourism policies and activities should be conducted with respect for the artistic, archaeological and cultural heritage, which they should protect and pass on to future generations; particular care should be devoted to preserving monuments, worship sites, archaeological and historic sites as well as upgrading museums which must be widely open and accessible to tourism visits”

UN Tourism Framework Convention on Tourism Ethics

Article 7, paragraph 2

This webpage provides UN Tourism resources aimed at strengthening the dialogue between tourism and culture and an informed decision-making in the sphere of cultural tourism. It also promotes the exchange of good practices showcasing inclusive management systems and innovative cultural tourism experiences .

About Cultural Tourism

According to the definition adopted by the UN Tourism General Assembly, at its 22nd session (2017), Cultural Tourism implies “A type of tourism activity in which the visitor’s essential motivation is to learn, discover, experience and consume the tangible and intangible cultural attractions/products in a tourism destination. These attractions/products relate to a set of distinctive material, intellectual, spiritual and emotional features of a society that encompasses arts and architecture, historical and cultural heritage, culinary heritage, literature, music, creative industries and the living cultures with their lifestyles, value systems, beliefs and traditions”. UN Tourism provides support to its members in strengthening cultural tourism policy frameworks, strategies and product development . It also provides guidelines for the tourism sector in adopting policies and governance models that benefit all stakeholders, while promoting and preserving cultural elements.

Recommendations for Cultural Tourism Key Players on Accessibility

UN Tourism , Fundación ONCE and UNE issued in September 2023, a set of guidelines targeting key players of the cultural tourism ecosystem, who wish to make their offerings more accessible.

The key partners in the drafting and expert review process were the ICOMOS International Cultural Tourism Committee and the European Network for Accessible Tourism (ENAT) . The ICOMOS experts’ input was key in covering crucial action areas where accessibility needs to be put in the spotlight, in order to make cultural experiences more inclusive for all people.

This guidance tool is also framed within the promotion of the ISO Standard ISO 21902 , in whose development UN Tourism had one of the leading roles.

Download here the English and Spanish version of the Recommendations.

Compendium of Good Practices in Indigenous Tourism

The report is primarily meant to showcase good practices championed by indigenous leaders and associations from the Region. However, it also includes a conceptual introduction to different aspects of planning, management and promotion of a responsible and sustainable indigenous tourism development.

The compendium also sets forward a series of recommendations targeting public administrations, as well as a list of tips promoting a responsible conduct of tourists who decide to visit indigenous communities.

For downloads, please visit the UN Tourism E-library page: Download in English - Download in Spanish .

Weaving the Recovery - Indigenous Women in Tourism

This initiative, which gathers UN Tourism , t he World Indigenous Tourism Alliance (WINTA) , Centro de las Artes Indígenas (CAI) and the NGO IMPACTO , was selected as one of the ten most promising projects amoung 850+ initiatives to address the most pressing global challenges. The project will test different methodologies in pilot communities, starting with Mexico , to enable indigenous women access markets and demonstrate their leadership in the post-COVID recovery.

This empowerment model , based on promoting a responsible tourism development, cultural transmission and fair-trade principles, will represent a novel community approach with a high global replication potential.

Visit the Weaving the Recovery - Indigenous Women in Tourism project webpage.

Inclusive Recovery of Cultural Tourism

The release of the guidelines comes within the context of the International Year of Creative Economy for Sustainable Development 2021 , a UN initiative designed to recognize how culture and creativity, including cultural tourism, can contribute to advancing the SDGs.

UN Tourism Inclusive Recovery Guide, Issue 4: Indigenous Communities

Sustainable Development of Indigenous Tourism

The Recommendations on Sustainable Development of Indigenous Tourism provide guidance to tourism stakeholders to develop their operations in a responsible and sustainable manner within those indigenous communities that wish to:

- Open up to tourism development, or

- Improve the management of the existing tourism experiences within their communities.

They were prepared by the UN Tourism Ethics, Culture and Social Responsibility Department in close consultation with indigenous tourism associations, indigenous entrepreneurs and advocates. The Recommendations were endorsed by the World Committee on Tourism Ethics and finally adopted by the UN Tourism General Assembly in 2019, as a landmark document of the Organization in this sphere.

Who are these Recommendations targeting?

- Tour operators and travel agencies

- Tour guides

- Indigenous communities

- Other stakeholders such as governments, policy makers and destinations

The Recommendations address some of the key questions regarding indigenous tourism:

Download PDF:

- Recommendations on Sustainable Development of Indigenous Tourism

- Recomendaciones sobre el desarrollo sostenible del turismo indígena, ESP

UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conferences on Tourism and Culture

The UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conferences on Tourism and Culture bring together Ministers of Tourism and Ministers of Culture with the objective to identify key opportunities and challenges for a stronger cooperation between these highly interlinked fields. Gathering tourism and culture stakeholders from all world regions the conferences which have been hosted by Cambodia, Oman, Türkiye and Japan have addressed a wide range of topics, including governance models, the promotion, protection and safeguarding of culture, innovation, the role of creative industries and urban regeneration as a vehicle for sustainable development in destinations worldwide.

Fourth UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conference on Tourism and Culture: Investing in future generations. Kyoto, Japan. 12-13 December 2019 Kyoto Declaration on Tourism and Culture: Investing in future generations ( English, French, Spanish, Arabic, Russian and Japanese )

Third UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conference on Tourism and Culture : For the Benefit of All. Istanbul, Türkiye. 3 -5 December 2018 Istanbul Declaration on Tourism and Culture: For the Benefit of All ( English , French , Spanish , Arabic , Russian )

Second UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conference’s on Tourism and Culture: Fostering Sustainable Development. Muscat, Sultanate of Oman. 11-12 December 2017 Muscat Declaration on Tourism and Culture: Fostering Sustainable Development ( English , French , Spanish , Arabic , Russian )

First UN Tourism/UNESCO World Conference’s on Tourism and Culture: Building a new partnership. Siem Reap, Cambodia. 4-6 February 2015 Siem Reap Declaration on Tourism and Culture – Building a New Partnership Model ( English )

UN Tourism Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage

The first UN Tourism Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage provides comprehensive baseline research on the interlinkages between tourism and the expressions and skills that make up humanity’s intangible cultural heritage (ICH).

Through a compendium of case studies drawn from across five continents, the report offers in-depth information on, and analysis of, government-led actions, public-private partnerships and community initiatives.

These practical examples feature tourism development projects related to six pivotal areas of ICH: handicrafts and the visual arts; gastronomy; social practices, rituals and festive events; music and the performing arts; oral traditions and expressions; and, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe.

Highlighting innovative forms of policy-making, the UN Tourism Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage recommends specific actions for stakeholders to foster the sustainable and responsible development of tourism by incorporating and safeguarding intangible cultural assets.

UN Tourism Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage

- UN Tourism Study

- Summary of the Study

Studies and research on tourism and culture commissioned by UN Tourism

- Tourism and Culture Synergies, 2018

- UN Tourism Study on Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage, 2012

- Big Data in Cultural Tourism – Building Sustainability and Enhancing Competitiveness (e-unwto.org)

Outcomes from the UN Tourism Affiliate Members World Expert Meeting on Cultural Tourism, Madrid, Spain, 1–2 December 2022

UN Tourism and the Region of Madrid – through the Regional Ministry of Culture, Tourism, and Sports – held the World Expert Meeting on Cultural Tourism in Madrid on 1 and 2 December 2022. The initiative reflects the alliance and common commitment of the two partners to further explore the bond between tourism and culture. This publication is the result of the collaboration and discussion between the experts at the meeting, and subsequent contributions.

Relevant Links

- 3RD UN Tourism/UNESCO WORLD CONFERENCE ON TOURISM AND CULTURE ‘FOR THE BENEFIT OF ALL’

Photo credit of the Summary's cover page: www.banglanatak.com

Cutting Edge | Bringing cultural tourism back in the game

The growth of cultural tourism

People have long traveled to discover and visit places of historical significance or spiritual meaning, to experience different cultures, as well as to learn about, exchange and consume a range of cultural goods and services. Cultural tourism as a concept gained traction during the 1990s when certain sub-sectors emerged, including heritage tourism, arts tourism, gastronomic tourism, film tourism and creative tourism. This took place amidst the rising tide of globalization and technological advances that spurred greater mobility through cheaper air travel, increased accessibility to diverse locations and cultural assets, media proliferation, and the rise of independent travel. Around this time, tourism policy was also undergoing a shift that was marked by several trends. These included a sharper focus on regional development, environmental issues, public-private partnerships, industry self-regulation and a reduction in direct government involvement in the supply of tourism infrastructure. As more cultural tourists have sought to explore the cultures of the destinations, greater emphasis has been placed on the importance of intercultural dialogue to promote understanding and tolerance. Likewise, in the face of globalization, countries have looked for ways to strengthen local identity, and cultural tourism has also been engaged as a strategy to achieve this purpose. Being essentially place-based, cultural tourism is driven by an interest to experience and engage with culture first-hand. It is backed by a desire to discover, learn about and enjoy the tangible and intangible cultural assets offered in a tourism destination, ranging from heritage, performing arts, handicrafts, rituals and gastronomy, among others.

Cultural tourism is a leading priority for the majority of countries around the world -featuring in the tourism policy of 90% of countries, based on a 2016 UNWTO global survey . Most countries include tangible and intangible heritage in their definition of cultural tourism, and over 80% include contemporary culture - film, performing arts, design, fashion and new media, among others. There is, however, greater need for stronger localisation in policies, which is rooted in promoting and enhancing local cultural assets, such as heritage, food, festivals and crafts. In France, for instance, the Loire Valley between Sully-sur-Loire and Chalonnes , a UNESCO World Heritage site, has established a multidisciplinary team that defends the cultural values of the site, and advises the authorities responsible for the territorial development of the 300 km of the Valley.

While cultural tourism features prominently in policies for economic growth, it has diverse benefits that cut across the development spectrum – economic, social and environmental. Cultural tourism expands businesses and job opportunities by drawing on cultural resources as a competitive advantage in tourism markets. Cultural tourism is increasingly engaged as a strategy for countries and regions to safeguard traditional cultures, attract talent, develop new cultural resources and products, create creative clusters, and boost the cultural and creative industries. Cultural tourism, particularly through museums, can support education about culture. Tourist interest can also help ensure the transmission of intangible cultural heritage practices to younger generations.

StockSnap, Pixabay

Cultural tourism can help encourage appreciation of and pride in local heritage, thus sparking greater interest and investment in its safeguarding. Tourism can also drive inclusive community development to foster resiliency, inclusivity, and empowerment. It promotes territorial cohesion and socioeconomic inclusion for the most vulnerable populations, for example, generating economic livelihoods for women in rural areas. A strengthened awareness of conservation methods and local and indigenous knowledge contributes to long-term environmental sustainability. Similarly, the funds generated by tourism can be instrumental to ensuring ongoing conservation activities for built and natural heritage.

The growth of cultural tourism has reshaped the global urban landscape over the past decades, strongly impacting spatial planning around the world. In many countries, cultural tourism has been leveraged to drive urban regeneration or city branding strategies, from large-sized metropolises in Asia or the Arab States building on cultural landmarks and contemporary architecture to drive tourism expansion, to small and middle-sized urban settlements enhancing their cultural assets to stimulate local development. At the national level, cultural tourism has also impacted planning decisions, encouraging coastal development in some areas, while reviving inland settlements in others. This global trend has massively driven urban infrastructure development through both public and private investments, impacting notably transportation, the restoration of historic buildings and areas, as well as the rehabilitation of public spaces. The expansion of cultural city networks, including the UNESCO World Heritage Cities programme and the UNESCO Creative Cities Network, also echoes this momentum. Likewise, the expansion of cultural routes, bringing together several cities or human settlements around cultural commonalities to stimulate tourism, has also generated new solidarities, while influencing economic and cultural exchanges between cities across countries and regions.

Despite tourism’s clear potential as a driver for positive change, challenges exist, including navigating the space between economic gain and cultural integrity. Tourism’s crucial role in enhancing inclusive community development can often remain at the margins of policy planning and implementation. Rapid and unplanned tourism growth can trigger a range of negative impacts, including pressure on local communities and infrastructure from overtourism during peak periods, gentrification of urban areas, waste problems and global greenhouse gas emissions. High visitor numbers to heritage sites can override their natural carrying capacity, thus undermining conservation efforts and affecting both the integrity and authenticity of heritage sites. Over-commercialization and folklorization of intangible heritage practices – including taking these practices out of context for tourism purposes - can risk inadvertently changing the practice over time. Large commercial interests can monopolize the benefits of tourism, preventing these benefits from reaching local communities. An excessive dependency on tourism can also create localized monoeconomies at the expense of diversification and alternative economic models. When mismanaged, tourism can, therefore, have negative effects on the quality of life and well-being of local residents, as well as the natural environment.

These fault lines became more apparent when the pandemic hit – revealing the extent of over-dependence on tourism and limited structures for crisis prevention and response. While the current situation facing tourism is unpredictable, making it difficult to plan, further crises are likely in the years to come. Therefore, the pandemic presents the opportunity to experiment with new models to shape more effective and sustainable alternatives for the future.

hxdyl, Getty Images Pro

Harnessing cultural tourism in policy frameworks

From a policy perspective, countries around the world have employed cultural tourism as a vehicle to achieve a range of strategic aims. In Panama, cultural tourism is a key component of the country’s recently adopted Master Plan for Sustainable Tourism 2020-2025 that seeks to position Panama as a worldwide benchmark for sustainable tourism through the development of unique heritage routes. Cultural tourism can be leveraged for cultural diplomacy as a form of ‘soft power’ to build dialogue between peoples and bolster foreign policy. For instance, enhancing regional cooperation between 16 countries has been at the heart of UNESCO’s transnational Silk Roads Programme, which reflects the importance of culture and heritage as part of foreign policy. UNESCO has also partnered with the EU and National Geographic to develop World Heritage Journeys, a unique travel platform that deepens the tourism experience through four selected cultural routes covering 34 World Heritage sites. Also in Europe, cultural tourism has been stimulated through the development of cultural routes linked to food and wine , as well as actions to protect local food products, such as through labels and certificates of origin. The Emilia-Romagna region in Italy, for example, produces more origin-protected food and drink than any other region in the country. One of the regions' cities Parma - a UNESCO Creative City (Gastronomy) and designated Italian Capital for Culture (2020-2021) - plans to resume its cultural activities to boost tourism once restrictions have eased. Meanwhile, Spain has recently taken steps to revive its tourism industry through its cities inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List . In this regard, the Group of the 15 Spanish World Heritage Cities met recently to discuss the country's Modernization and Competitiveness Plan for the tourism sector. Cultural tourism has progressively featured more prominently in the policies of Central Asian and Eastern European countries, which have sought to revive intangible heritage and boost the creative economy as part of strategies to strengthen national cultural identity and open up to the international community. In Africa, cultural tourism is a growing market that is driven by its cultural heritage, crafts, and national and regional cultural events. Major festivals such as Dak-Art in Senegal, Bamako Encounters Photography Biennial in Mali, Sauti za Busara in United Republic of Tanzania, Pan-African Festival of Cinema and Television of Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso, and Chale Wote Street Art Festival in Ghana are just a handful of vibrant and popular platforms in the continent that share cultural expressions, generate income for local economies and strengthen Pan-African identity.

Countries are increasingly seeking alliances with international bodies to advance tourism. National and local governments are working together with international entities, such as UNESCO, UNWTO and OECD in the area of sustainable tourism. In 2012, UNESCO’s Sustainable Tourism Programme was adopted, thereby breaking new ground to promote tourism a driver for the conservation of cultural and natural heritage and a vehicle for sustainable development. In 2020, UNESCO formed the Task Force on Culture and Resilient Tourism with the Advisory Bodies to the 1972 World Heritage Convention (ICOMOS, IUCN, ICCROM) as a global dialogue platform on key issues relating to tourism and heritage management during and beyond the crisis. UNESCO has also collaborated with the UNWTO on a set of recommendations for inclusive cultural tourism recovery from the COVID-19 crisis. In response to the crisis, the Namibian Government, UNESCO and UNDP are working together on a tourism impact study and development strategy to restore the tourism sector, especially cultural tourism.

UNESCO has scaled up work in cultural tourism in its work at field level, supporting its Member States and strengthening regional initiatives. In the Africa region, enhancing cultural tourism has been reported as a policy priority across the region. For example, UNESCO has supported the Government of Ghana in its initiative Beyond the Return, in particular in relation to its section on cultural tourism. In the Pacific, a Common Country Assessment (CCA) has been carried out for 14 SIDS countries, with joint interagency programmes to be created building on the results. Across the Arab States, trends in tourism after COVID, decent jobs and cultural and creative industries are emerging as entry points for different projects throughout the region. In Europe, UNESCO has continued its interdisciplinary work on visitor centres in UNESCO designated sites, building on a series of workshops to strengthen tourism sustainability, community engagement and education through heritage interpretation. In the Latin America and the Caribbean region, UNESCO is working closely with Member States, regional bodies and the UN system building on the momentum on the International Year of Creative Economy for Sustainable Development, including through Creative Cities, and the sustainable recovery of the orange economy, among others.

BS1920, Pixabay

In the context of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, tourism has the potential to contribute, directly or indirectly, to all of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Tourism is directly mentioned in SDGs 8, 12 and 14 on inclusive and sustainable economic growth, sustainable consumption and production (SCP) and the sustainable use of oceans and marine resources, respectively. This is mirrored in the VNRs put forward by countries, who report on cultural tourism notably through the revitalization of urban and rural areas through heritage regeneration, festivals and events, infrastructure development, and the promotion of local cultural products. The VNRs also demonstrate a trend towards underlining more sustainable approaches to tourism that factor in the environmental dimensions of tourism development.

Several countries have harnessed cultural tourism as a policy panacea for economic growth and diversification. As part of Qatar's National Vision 2030 strategy, for example, the country has embarked on a development plan that includes cultural tourism through strengthening its culture-based industries, including calligraphy, handicrafts and living heritage practices. In the city of Abu Dhabi in the UAE, cultural tourism is part of the city’s plan for economic diversification and to steer its domestic agenda away from a hydrocarbon-based economy. The Plan Abu Dhabi 2030 includes the creation of a US$27 billion cultural district on Saadiyat Island, comprising a cluster of world-renowned museums, and cultural and educational institutions designed by international star architects to attract tourism and talent to the city. Since 2016, Saudi Arabia has taken decisive action to invest in tourism, culture and entertainment to reduce the country’s oil dependency, while also positioning the country as a global cultural destination. Under the 2020 G20 Saudi Presidency, the UNWTO and the G20 Tourism Working Group launched the AlUla Framework for Inclusive Community Development through Tourism to better support inclusive community development and the SDGs. The crucial role of tourism as a means of sustainable socio-economic development was also underlined in the final communique of the G20 Tourism Ministers in October last.

Siem Reap, Cambodia by nbriam

On the other hand, cultural tourism can catalyse developments in cultural policy. This was the case in the annual Festival of Pacific Arts (FestPac) that triggered a series of positive policy developments following its 2012 edition that sought to strengthen social cohesion and community pride in the context of a prolonged period of social unrest. The following year, Solomon Islands adopted its first national culture policy with a focus on cultural industries and cultural tourism, which resulted in a significant increase in cultural events being organized throughout the country.

When the pandemic hit, the geographic context of some countries meant that many of them were able to rapidly close borders and prioritize domestic tourism. This has been the case for countries such as Australia and New Zealand. However, the restrictions have been coupled by significant economic cost for many Small Island Developing States (SIDS) whose economies rely on tourism and commodity exports. Asia Pacific SIDS, for example, are some of the world’s leading tourist destinations. As reported in the Tracker last June , in 2018, tourism earnings exceeded 50% of GDP in Cook Islands, Maldives and Palau and equaled approximately 30% of GDP in Samoa and Vanuatu. When the pandemic hit in 2020, the drop in British tourists to Spain’s Balearic Islands resulted in a 93% downturn in visitor numbers , forcing many local businesses to close. According to the World Economic Outlook released last October, the economies of tourism-dependent Caribbean nations are estimated to drop by 12%, while Pacific Island nations, such as Fiji, could see their GDP shrink by a staggering 21% in 2020.

Socially-responsible travel and ecotourism have become more of a priority for tourists and the places they visit. Tourists are increasingly aware of their carbon footprint, energy consumption and the use of renewable resources. This trend has been emphasized as a result of the pandemic. According to recent survey by Booking.com, travelers are becoming more conscientious of how and why they travel, with over two-thirds (69%) expecting the travel industry to offer more sustainable travel options . Following the closures of beaches in Thailand, for example, the country is identifying ways to put certain management policies in place that can strike a better balance with environmental sustainability. The UNESCO Sustainable Tourism Pledge launched in partnership with Expedia Group focuses on promoting sustainable tourism and heritage conservation. The pledge takes an industry-first approach to environmental and cultural protection, requiring businesses to introduce firm measures to eliminate single-use plastics and promote local culture. The initiative is expanding globally in 2021 as a new, more environmentally and socially conscious global travel market emerges from the COVID-19 context.

Senja, Norway by Jarmo Piironen

Climate change places a heavy toll on heritage sites, which exacerbates their vulnerability to other risks, including uncontrolled tourism. This was underlined in the publication “World Heritage and Tourism in a Changing Climate” , published by UNESCO, UNEP and the Union of Concerned Scientists, which analyses the consequences of climate change on heritage, and its potential to permanently change or destroy a site’s integrity and authenticity. Extreme weather events, safety issues and water shortages, among others, can thwart access to sites and hurt the economic livelihoods of tourism service providers and local communities. Rising sea levels will increasingly impact coastal tourism, the largest component of the sector globally. In particular, coral reefs - contributing US$11.5 billion to the global tourism economy – are at major risk from climate change.

Marine sites are often tourist magnets where hundreds of thousands of annual visitors enjoy these sites on yachts and cruise ships. In the case of UNESCO World Heritage marine sites – which fall under the responsibility of governments - there is often a reliance on alternative financing mechanisms, such as grants and donations, and partnerships with non-governmental organizations and/or the private sector, among others. The West Norwegian Fjords – Geirangerfjord and Nærøyfjord in Norway derives a substantial portion of its management budget from sources other than government revenues. The site has benefited from a partnership with the private sector company Green Dream 2020, which only allows the “greenest” operators to access the site, and a percentage of the profits from tours is reinjected into the long-term conservation of the site. In iSimangaliso in South Africa, a national law that established the World Heritage site’s management system was accompanied by the obligation to combine the property’s conservation with sustainable economic development activities that created jobs for local people. iSimangaliso Wetland Park supports 12,000 jobs and hosts an environmental education programme with 150 schools. At the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, where 91% of all local jobs are linked to the Reef, the Coral Nurture Programme undertakes conservation through planting coral, and promotes local stewardship and adaptation involving the whole community and local tourist businesses.

Grafner, Getty Images

With borders continuing to be closed and changeable regulations, many countries have placed a focus on domestic tourism and markets to stimulate economic recovery. According to the UNWTO, domestic tourism is expected to pick up faster than international travel, making it a viable springboard for economic and social recovery from the pandemic. In doing so it will serve to better connect populations to their heritage and offer new avenues for cultural access and participation. In China, for example, the demand for domestic travel is already approaching pre-pandemic levels. In Russian Federation, the Government has backed a programme to promote domestic tourism and support small and medium-sized enterprises, as well as a cashback scheme for domestic trips, which entitles tourists to a 20% refund for their trip. While supporting domestic tourism activities, the Government of Palau is injecting funds into local businesses working in reforestation and fishing in the spirit of building new sustainable models. The measures put in place today will shape the tourism to come, therefore the pandemic presents an opportunity to build back a stronger, more agile and sustainable tourism sector.

Local solutions at the helm of cultural tourism

While state-led policy interventions in cultural tourism remain crucial, local authorities are increasingly vital stakeholders in the design and implementation of cultural tourism policies. Being close to the people, local actors are aware of the needs of local populations, and can respond quickly and provide innovative ideas and avenues for policy experimentation. As cultural tourism is strongly rooted to place, cooperating with local decision-makers and stakeholders can bring added value to advancing mutual objectives. Meanwhile, the current health crisis has severely shaken cities that are struggling due to diminished State support, and whose economic basis strongly relies on tourism. Local authorities have been compelled to innovate to support local economies and seek viable alternatives, thus reaffirming their instrumental role in cultural policy-making.

Venice, Oliver Dralam/Getty Images

Cultural tourism can be a powerful catalyst for urban regeneration and renaissance, although tourism pressure can also trigger complex processes of gentrification. Cultural heritage safeguarding enhances the social value of a place by boosting the well-being of individuals and communities, reducing social inequalities and nurturing social inclusion. Over the past decade, the Malaysian city of George Town – a World Heritage site – has implemented several innovative projects to foster tourism and attract the population back to the city centre by engaging the city’s cultural assets in urban revitalization strategies. Part of the income generated from tourism revenues contributes to conserving and revitalizing the built environment, as well as supporting housing for local populations, including lower-income communities. In the city of Bordeaux in France , the city has worked with the public-private company InCité to introduce a system of public subsidies and tax exemption to encourage the restoration of privately-owned historical buildings, which has generated other rehabilitation works in the historic centre. The city of Kyoto in Japan targets a long-term vision of sustainability by enabling local households to play an active role in safeguarding heritage by incrementally updating their own houses, thus making the city more resilient to gentrification. The city also actively supports the promotion of its intangible heritage, such as tea ceremonies, flower arrangement, seasonal festivals, Noh theatre and dance. This year marks the ten-year anniversary of the adoption of the UNESCO Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL). The results of a UNESCO survey carried out among Member States in 2019 on its implementation show that 89% of respondents have innovative services or tourism activities in place for historic areas, which demonstrates a precedence for countries to capitalize on urban cultural heritage for tourism purposes.

Cultural tourism has been harnessed to address rural-urban migration and to strengthen rural and peripheral sub-regions. The city of Suzhou – a World Heritage property and UNESCO Creative City (Crafts and Folk Art) - has leveraged its silk embroidery industry to strengthen the local rural economy through job creation in the villages of Wujiang, located in a district of Suzhou. Tourists can visit the ateliers and local museums to learn about the textile production. In northern Viet Nam, the cultural heritage of the Quan họ Bắc Ninh folk songs, part of the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, is firmly rooted in place and underlined in its safeguarding strategies in 49 ancient villages, which have further inspired the establishment of some hundreds of new Quan họ villages in the Bắc Ninh and Bắc Giang provinces.

Many top destination cities are known for their iconic cultural landmarks. Others create a cultural drawcard to attract visitors to the city. France, the world's number one tourist destination , attracts 89 million visitors every year who travel to experience its cultural assets, including its extensive cultural landmarks. In the context of industrial decline, several national and local governments have looked to diversify infrastructure by harnessing culture as a new economic engine. The Guggenheim museum in Bilbao in Spain is one such example, where economic diversification and unemployment was addressed through building a modern art museum as a magnet for tourism. The museum attracts an average of 900,000 visitors annually, which has strengthened the local economy of the city. A similar approach is the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA), established in 2011 by a private entrepreneur in the city of Hobart in Australia, which has catalysed a massive increase of visitors to the city. With events such as MONA FOMA in summer and Dark MOFO in winter, the museum staggers visitor volumes to the small city to avoid placing considerable strain on the local environment and communities. Within the tourism sector, cultural tourism is also well-positioned to offer a tailored approach to tourism products, services and experiences. Such models have also supported the wider ecosystems around the iconic cultural landmarks, as part of “destination tourism” strategies.

Destination tourism encompasses festivals, live performance, film and festive celebrations as drawcards for international tourists and an economic driver of the local economy. Over the past three decades, the number of art biennials has proliferated. Today there are more than 300 biennials around the world , whose genesis can be based both on artistic ambitions and place-making strategies to revive specific destinations. As a result of COVID-19, many major biennials and arts festivals have been cancelled or postponed. Both the Venice Architecture and Art Biennales have been postponed to 2022 due to COVID-19. The Berlin International Film Festival will hold its 2021 edition online and in selected cinemas. Film-induced tourism - motivated by a combination of media expansion, entertainment industry growth and international travel - has also been used for strategic regional development, infrastructure development and job creation, as well to market destinations to tourists. China's highest-grossing film of 2012 “Lost in Thailand”, for example, resulted in a tourist boom to Chiang Mai in Thailand, with daily flights to 17 Chinese cities to accommodate the daily influx of thousands of tourists who came to visit the film’s location. Since March 2020, tourism-related industries in New York City in the United States have gone into freefall, with revenue from the performing arts alone plunging by almost 70%. As the city is reliant on its tourism sector, the collapse of tourism explains why New York’s economy has been harder hit than other major cities in the country. Meanwhile in South Africa, when the first ever digital iteration of the country’s annual National Arts Festival took place last June, it also meant an estimated US$25.7 million (R377 million) and US$6.4 million (R94 million) loss to the Eastern Cape province and city of Makhanda (based on 2018 figures), in addition to the US$1.4 million (R20 million) that reaches the pockets of the artists and supporting industries. The United Kingdom's largest music festival, Glastonbury, held annually in Somerset, recently cancelled for the second year running due to the pandemic, which will have ripple effects on local businesses and the charities that receive funding from ticket sales.

Similarly, cancellations of carnivals from Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Canary Islands to Binche in Belgium has spurred massive losses for local tourism providers, hotels, restaurants, costume-makers and dance schools. In the case of the Rio de Janeiro Carnival in Brazil, for instance, the city has amassed significant losses for the unstaged event, which in 2019 attracted 1.5 million tourists from Brazil and abroad and generated revenues in the range of US$700 million (BRL 3.78 billion). The knock-on effect on the wider economy due to supply chains often points to an estimated total loss that is far greater than those experienced solely by the cultural tourism sector.

Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain by erlucho

Every year, roughly 600 million national and international religious and spiritual trips take place , generating US$18 billion in tourism revenue. Pilgrimages, a fundamental precursor to modern tourism, motivate tourists solely through religious practices. Religious tourism is particularly popular in France, India, Italy and Saudi Arabia. For instance, the Hindu pilgrimage and festival Kumbh Mela in India, inscribed in 2017 on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, attracts over 120 million pilgrims of all castes, creeds and genders. The festival is held in the cities of Allahabad, Haridwar, Ujjain and Nasik every four years by rotation. Sacred and ceremonial sites have unique significance for peoples and communities, and are often integral to journeys that promote spiritual well-being. Mongolia, for example, has around 800 sacred sites including 10 mountains protected by Presidential Decree, and lakes and ovoos, many of which have their own sutras. In the case of Mongolia, the environmental stewardship and rituals and practices connected with these sacred places also intersects with longstanding political traditions and State leadership.

Cities with a vibrant cultural scene and assets are not only more likely to attract tourists, but also the skilled talent who can advance the city’s long-term prospects. Several cities are also focusing on developing their night-time economies through the promotion of theatre, concerts, festivals, light shows and use of public spaces that increasingly making use of audio-visual technologies. Situated on Chile’s Pacific coast, the city of Valparaíso, a World Heritage site, is taking steps to transform the city’s night scene into a safe and inclusive tourist destination through revitalizing public spaces. While the economies of many cities have been weakened during the pandemic, the night-time economy of the city of Chengdu in China, a UNESCO Creative City for Gastronomy, has flourished and has made a significant contribution to generating revenue for the city, accounting for 45% of citizen’s daily expenditure.

The pandemic has generated the public’s re-appropriation of the urban space. People have sought open-air sites and experiences in nature. In many countries that are experiencing lockdowns, public spaces, including parks and city squares, have proven essential for socialization and strengthening resilience. People have also reconnected with the heritage assets in their urban environments. Local governments, organizations and civil society have introduced innovative ways to connect people and encourage creative expression. Cork City Council Arts Office and Creative Ireland, for example, jointly supported the art initiative Ardú- Irish for ‘Rise’ – involving seven renowned Irish street artists who produced art in the streets and alleyways of Cork.

Chengdu Town Square, China by Lukas Bischoff

Environment-based solutions support integrated approaches to deliver across the urban-rural continuum, and enhance visitor experiences by drawing on the existing features of a city. In the city of Bamberg, a World Heritage site in Germany, gardens are a key asset of the city and contribute to its livability and the well-being of its local population and visitors. More than 12,000 tourists enjoy this tangible testimony to the local history and environment on an annual basis. Eighteen agricultural businesses produce local vegetables, herbs, flowers and shrubs, and farm the inner-city gardens and surrounding agricultural fields. The museum also organizes gastronomic events and cooking classes to promote local products and recipes.

In rural areas, crafts can support strategies for cultural and community-based tourism. This is particularly the case in Asia, where craft industries are often found in rural environments and can be an engine for generating employment and curbing rural-urban migration. Craft villages have been established in Viet Nam since the 11th century, constituting an integral part of the cultural resources of the country, and whose tourism profits are often re-invested into the sustainability of the villages. The craft tradition is not affected by heavy tourist seasons and tourists can visit all year round.

Indigenous tourism can help promote and maintain indigenous arts, handicrafts, and culture, including indigenous culture and traditions, which are often major attractions for visitors. Through tourism, indigenous values and food systems can also promote a less carbon-intensive industry. During COVID-19, the Government of Canada has given a series of grants to indigenous tourism businesses to help maintain livelihoods. UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Committee for the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions announced that it will grant, through the International Fund for Creative Diversity (IFCD), US$70,000 dollars to Mexican indigenous cultural enterprises, which will support indigenous enterprises through training programmes, seed funding, a pre-incubation process and the creation of an e-commerce website.

Tourism has boosted community pride in living heritage and the active involvement of local communities in its safeguarding. Local authorities, cultural associations, bearers and practitioners have made efforts to safeguard and promote elements as they have understood that not only can these elements strengthen their cultural identity but that they can also contribute to tourism and economic development. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the role of intellectual property and in the regulation of heritage. In the field of gastronomy, a lot of work has been done in protecting local food products, including the development of labels and certification of origin. Member States are exploring the possibilities of geographical indication (GI) for cultural products as a way of reducing the risk of heritage exploitation in connection to, for example, crafts, textiles and food products, and favouring its sustainable development.

The pandemic has brought to the forefront the evolving role of museums and their crucial importance to the life of societies in terms of health and well-being, education and the economy. A 2019 report by the World Health Organization (WHO) examined 3,000 studies on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being, which indicated that the arts play a major role in preventing, managing and treating illness. Over the past decade the number of museums has increased by 60%, demonstrating the important role that museums have in national cultural policy. Museums are not static but are rather dynamic spaces of education and dialogue, with the potential to boost public awareness about the value of cultural and natural heritage, and the responsibility to contribute to its safeguarding.

Data presented in UNESCO's report "Museums Around the World in the Face of COVID-19" in May 2020 show that 90% of institutions were forced to close, whereas the situation in September-October 2020 was much more variable depending on their location in the world. Large museums have consistently been the most heavily impacted by the drop in international tourism – notably in Europe and North America. Larger museums, such as Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum and Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum have reported losses between €100,000 and €600,000 a week. Smaller museums have been relatively stable, as they are not as reliant on international tourism and have maintained a closer connection to local communities. In November, the Network of European Museum Organisations (NEMO) released the results of a survey of 6,000 museums from 48 countries. Of the responding museums, 93% have increased or started online services during the pandemic. Most larger museums (81%) have increased their digital capacities, while only 47% of smaller museums indicated that they did. An overwhelming majority of respondents (92.9%) confirm that the public is safe at their museum. As reported in the Tracker last October, the world’s most visited museum, the Louvre in France (9.3 million visitors annually) witnessed a ten-fold increase in traffic to its website. Yet while digital technologies have provided options for museums to remain operational, not all have the necessary infrastructure, which is the case for many museums in Africa and SIDS.

New technologies have enabled several new innovations that can better support cultural tourism and digital technologies in visitor management, access and site interpretation. Cultural tourists visiting cultural heritage sites, for example, can enjoy educational tools that raise awareness of a site and its history. Determining carrying capacity through algorithms has helped monitor tourist numbers, such as in Hạ Long Bay in Viet Nam. In response to the pandemic, Singapore’s Asian Civilizations Museum is one of many museums that has harnessed digital technologies to provide virtual tours of its collections, thus allowing viewers to learn more about Asian cultures and histories. The pandemic has enhanced the need for technology solutions to better manage tourism flows at destinations and encourage tourism development in alternative areas.

Shaping a post-pandemic vision : regenerative and inclusive cultural tourism

As tourism is inherently dependent on the movement and interaction of people, it has been one of the hardest-hit sectors by the pandemic and may be one of the last to recover. Travel and international border restrictions have led to the massive decline in tourism in 2020, spurring many countries to implement strategies for domestic tourism to keep economies afloat. Many cultural institutions and built and natural heritage sites have established strict systems of physical distancing and hygiene measures, enabling them to open once regulations allow. Once travel restrictions have been lifted, it will enable the recovery of the tourism sector and for the wider economy and community at large.

While the pandemic has dramatically shifted the policy context for cultural tourism, it has also provided the opportunity to experiment with integrated models that can be taken forward in the post-pandemic context. While destinations are adopting a multiplicity of approaches to better position sustainability in their plans for tourism development, there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

A comprehensive, integrated approach to the cultural sector is needed to ensure more sustainable cultural tourism patterns. Efforts aimed at promoting cultural tourism destinations should build on the diversity of cultural sub-sectors, including cultural and heritage sites, museums, but also the creative economy and living heritage, notably local practices, food and crafts production. Beyond cultural landmarks, which act as a hotspot to drive the attractiveness of tourism destinations, and particularly cities, cultural tourism should also encompass other aspects of the cultural value chain as well as more local, community-based cultural expressions. Such an integrated approach is likely to support a more equitable distribution of cultural tourism revenues, also spreading tourism flows over larger areas, thus curbing the negative impacts of over-tourism on renowned cultural sites, including UNESCO World Heritage sites. This comprehensive vision also echoes the growing aspiration of visitors around the world for more inclusive and sustainable tourism practices, engaging with local communities and broadening the understanding of cultural diversity.

As a result of the crisis, the transversal component of cultural tourism has been brought to the fore, demonstrating its cross-cutting nature and alliance with other development areas. Cultural tourism – and tourism more broadly – is highly relevant to the 2030 for Sustainable Development and its 17 SDGs, however, the full potential of cultural tourism for advancing development – economic, social and environmental - remains untapped. This is even though cultural tourism is included in a third of all countries’ VNRs, thus demonstrating its priority for governments. Due the transversal nature of cultural tourism, there is scope to build on these synergies and strengthen cooperation between ministries to advance cooperation for a stronger and more resilient sector. This plays an integral role in ensuring a regenerative and inclusive cultural tourism sector. Similarly, tourism can feature as criteria for certain funding initiatives, or as a decisive component for financing cultural projects, such as in heritage or the cultural and creative industries.

Houses in Amsterdam, adisa, Getty, Images Pro

Several countries have harnessed the crisis to step up actions towards more sustainable models of cultural tourism development by ensuring that recovery planning is aligned with key sustainability principles and the SDGs. Tourism both impacts and is impacted by climate change. There is scant evidence of integration of climate strategies in tourism policies, as well as countries’ efforts to develop solid crisis preparedness and response strategies for the tourism sector. The magnitude and regional variation of climate change in the coming decades will continue to affect cultural tourism, therefore, recovery planning should factor in climate change concerns. Accelerating climate action is of utmost importance for the resilience of the sector.

The key role of local actors in cultural tourism should be supported and developed. States have the opportunity to build on local knowledge, networks and models to forge a stronger and more sustainable cultural tourism sector. This includes streamlining cooperation between different levels of governance in the cultural tourism sector and in concert with civil society and private sector. Particularly during the pandemic, many cities and municipalities have not received adequate State support and have instead introduced measures and initiatives using local resources. In parallel, such actions can spur new opportunities for employment and training that respond to local needs.

Greater diversification in cultural tourism models is needed, backed by a stronger integration of the sector within broader economic and regional planning. An overdependence of the cultural sector on the tourism sector became clear for some countries when the pandemic hit, which saw their economies come to a staggering halt. This has been further weakened by pre-existing gaps in government and industry preparedness and response capacity. The cultural tourism sector is highly fragmented and interdependent, and relies heavily on micro and small enterprises. Developing a more in-depth understanding of tourism value chains can help identify pathways for incremental progress. Similarly, more integrated – and balanced – models can shape a more resilient sector that is less vulnerable to future crises. Several countries are benefiting from such approaches by factoring in a consideration of the environmental and socio-cultural pillars of sustainability, which is supported across all levels of government and in concert with all stakeholders.

abhishek gaurav, Pexels

Inclusion must be at the heart of building back better the cultural tourism sector. Stakeholders at different levels should participate in planning and management, and local communities cannot be excluded from benefitting from the opportunities and economic benefits of cultural tourism. Moreover, they should be supported and empowered to create solutions from the outset, thus forging more sustainable and scalable options in the long-term. Policy-makers need to ensure that cultural tourism development is pursued within a wider context of city and regional strategies in close co-operation with local communities and industry. Businesses are instrumental in adopting eco-responsible practices for transport, accommodation and food. A balance between public/ private investment should also be planned to support an integrated approach post-crisis, which ensures input and support from industry and civil society.

The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the essential role of museums as an integral component of societies in terms of well-being, health, education and the economy. Digitalization has been a game-changer for many cultural institutions to remain operational to the greatest extent possible. Yet there are significant disparities in terms of infrastructure and resources, which was underscored when the world shifted online. Museums in SIDS have faced particular difficulties with lack of access to digitalization. These imbalances should be considered in post-crisis strategies.

The pandemic presents an occasion to deeply rethink tourism for the future, and what constitutes the markers and benchmarks of “success”. High-quality cultural tourism is increasingly gaining traction in new strategies for recovery and revival, in view of contributing to the long-term health and resilience of the sector and local communities. Similarly, many countries are exploring ways to fast track towards greener, more sustainable tourism development. As such, the pandemic presents an opportunity for a paradigm shift - the transformation of the culture and tourism sectors to become more inclusive and sustainable. Moreover, this includes incorporating tourism approaches that not only avoid damage but have a positive impact on the environment of tourism destinations and local communities. This emphasis on regenerative tourism has a holistic approach that measures tourism beyond its financial return, and shifts the pendulum towards focusing on the concerns of local communities, and the wellbeing of people and planet.

Entabeni Game Reserve in South Africa by SL_Photography

Related items

More on this subject.

Other recent news

- Switch skin

What is Cultural Tourism and Why is It Important?

Tourism trends come and go. What was once deemed as a necessity in travel and tourism may not be a necessity today. So what is cultural tourism and why is it important? Let’s dive in!

How is Culture Defined?

In order to understand cultural tourism, we must first understand what constitutes culture.

Culture is rooted in many complexities and many inner workings. On the surface level, culture can be defined through symbols, words, gestures, people, rituals and more.

However, the core of culture is in its values.

The way a culture perceives itself or stays preserved is through a set of shared values.

Maybe its an ode to ancestry and tradition or a new breadth of

However, the core of culture is in its values.

Whether it’s an ode to ancestry or creating a new set of values as time evolves, it can be also be held true to the

Whether it’s an ode to ancestry or creating a new set of values as time evolves, cultural tourism is uprooted in holding and preserving cultures through traditions and heritage. [1]

What is Cultural Tourism?

Adopted by the UNWTO General Assembly in 2017, Cultural Tourism is defined as the following: “A type of tourism activity in which the visitor’s essential motivation is to learn, discover, experience and consume tangible and intangible cultural attractions/products in a tourism destination.”

The main aim of cultural tourism is to improve the quality and livelihood of the local people who are committed to preserving cultural heritage and traditions.

This can be through the purchase of locally made goods, initiatives through local food and the learning of recipes,